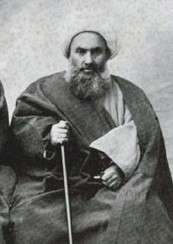

Sheikh Fazlollah bin Abbas Mazindarani (Persian: فضلالله بن عباس مازندرانی; 24 December 1843 – 31 July 1909), also known as Fazlollah Noori (Persian: فضلالله نوری), was a major figure in Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911) as a Twelver Shia Muslim scholar and politically connected mullah of the court of Iran's Shah. Originally a supporter of the constitution, he turned against it after the supporting constitution shah died and was replaced by one opposing the constitution. He was hanged as a traitor in 1909 by a court of the constitutionalist government for "sowing corruption and sedition on earth".[1]

Fazlollah Noori | |

|---|---|

شيخ فضلالله نوری | |

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | December 24, 1843 |

| Died | July 31, 1909 (aged 65) Tehran, Iran |

| Resting place | Fatima Masumeh Shrine |

| Religion | Islam |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Parent | Abbas Mazandarani (father) |

| Jurisprudence | Twelver Shia Islam |

| Muslim leader | |

| Successor | Ruhollah Khomeini |

In the Islamic Republic of Iran he is celebrated for defending Sharia law and Islam against agents of the West, and portrayed in school textbooks as a martyr (shahid) to Islam and the motherland.[2][3][4][5] Among historians outside of Iran he is known for having originally supported the constitutionalist revolution but having reversed himself when it was no longer politically expedient, for being "responsible for the murder of leading constitutionalists"[2] by inciting mobs and issuing fatwas declaring parliamentary leaders "apostates", "atheists," "secret masons" and koffar al-harbi (warlike pagans) whose blood ought to be shed by the faithful;[6][1] and (contrary to the mythology his opposing foreigners encroaching on Iran's culture, economy and society) for having taken money and given support to foreign interests in Iran.[7]

Nouri was a financially successful court official responsible for collected religious funds, for conducting marriages and contracts, including the wills of wealthy men.[8] Under the monarch Mozaffar al-Din Shah, who accepted demands for democratic reforms and agreed to surrender political powers to the parliament, he sided with the Iranian Constitutional Revolution. However, Noori turned against the revolution after Mozaffar al-Din's death and his successor (Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar) moved to close the parliament and return to the country to monarchical absolutism.[9] He joined the Shah in a vigorous propaganda campaign against modern parliamentary system, insisting that the role of the elected parliament (majles) was as a forum for consultation, whereas the laws should come only from Sharia.[10][11]

Early life

editNoori was son of cleric Mulla Abbas Kijouri. After receiving his early education in Kojour and Tehran, Sheikh Fazlollah moved to Iraq shrine cities where he studied under a prominent Shia scholar, Mirza Hasan Shirazi. After returning to Tehran he grew to become a prominent scholar and teacher. Businessmen and officials also referred to him for settling their legal cases. He wrote some leaflets and books on religion. He is reported to have enjoyed high respect in King's court.[12]

Fazlullah changed his political stance according to his evaluation of the power equation. In 1880s, Fazlullah was drawn into politics in response to the Qajar government's increasing business concession to foreign businessmen. Drawing upon the views of his mentor, Shirazi, he argued that during the period of Occultation, running the country has to be a shared responsibility of the King and clerics.[12] Sheikh Fazl Allah played some role in the successful Tobacco protest movement against concession of Tobacco monopoly to the British Regie Company.[12] After demise of pro-democracy Mozzafar ad-Din Shah, Nouri saw that the new King Muhammad Ali Shah was against the parliament and sided with him.[13]

The controversy over democracy

editThe fourth Qajar King, Naser al-Din Shah was assassinated by Mirza Reza Kermani, a follower of Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, when he was visiting and praying in the Shah Abdul-Azim Shrine on 1 May 1896. At Mozaffar al-Din Shah's accession Persia faced a financial crisis, with annual governmental expenditures far in excess of revenues as a result of the policies of his father. During his reign, Mozzafar ad-Din attempted some reforms of the central treasury; however, the previous debt incurred by the Qajar court, owed to both England and Russia, significantly undermined this effort. He awarded William Knox D'Arcy, a British subject, the rights to oil in most of the country in 1901.[14] Widespread fears amongst the aristocracy, educated elites, and religious leaders about the concessions and foreign control resulted in some protests in 1906. The three main groups of the coalition seeking a constitution were the merchants, the ulama, and a small group of radical reformers. They shared the goal of ending royal corruption and ending dominance by foreign powers. These resulted in the Shah accepting a suggestion to create a Majles (National Consultative Assembly) in October 1906, by which the monarch's power was curtailed as he granted a constitution and parliament to the people. King Mozaffar ad-Din Shah signed the 1906 constitution shortly before his death. The members of newly formed parliament stayed constantly in touch with Akhund Khurasani and whenever legislative bills were discussed, he was telegraphed the details for a juristic opinion.[15] In a letter dated June 3, 1907, the parliament told Akhund Khurasani about a group of anti-constitutionalists who were trying to undermine legitimacy of democracy in the name of religious law. The trio replied:[15][16]

اساس این مجلس محترم مقدس بر امور مذکور مبتنی است. بر هر مسلمی سعی و اهتمام در استحکام و تشیید این اساس قویم لازم، و اقدام در موجبات اختلال آن محاده و معانده با صاحب شریعت مطهره علی الصادع بها و آله الطاهرین افضل الصلاه و السلام، و خیانت به دولت قوی شوکت است.

الاحقر نجل المرحوم الحاج میرزا خلیل قدس سره محمد حسین، حررّہ الاحقر الجانی محمد کاظم الخراسانی، من الاحقر عبدالله المازندرانی [17]

"Because we are aware of the intended reasons for this institution, it is therefore incumbent on every Muslim to support its foundation, and those who try to defeat it, and their action against it, are considered contrary to shari'a."

— Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

At the dawn of the democratic movement, Sheikh Fadlullah Nouri, supported the sources of emulation in Najaf in their stance on constitutionalism and the belief that people must counter the autocratic regime in the best way, that is constitution of legislature and limiting the powers of the state; hence, once constitutional movement began, he made speeches and distributed tracts to insist on this important thing. However, when the new Shah, Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar, decided to role back democracy and establish his authority by military and foreign support, Shaikh Fazlullah sided with the King's court.[9]

Meanwhile, the new Shah had understood that he could not roll back the constitutional democracy by royalist ideology, and therefore he decided to use the religion card.[18] Nouri was a rich and high-ranking Qajar court official responsible for conducting marriages and contracts. He also handled wills of wealthy men and collected religious funds.[8] Nouri was opposed to the very foundations of the institution of parliament. He led a large group of followers and began a round-the-clock sit-in in the Shah Abdul Azim shrine on June 21, 1907, which lasted till September 16, 1907. He generalized the idea of religion as a complete code of life to push for his own agenda. He believed democracy will allow for "teaching of chemistry, physics and foreign languages", that would result in spread of Atheism.[19][20] He bought a printing press and launched a newspaper of his own for propaganda purposes, "Ruznamih-i-Shaikh Fazlullah", and published leaflets.[21] He said:

Shari'a covers all regulations of government, and specifies all obligations and duties, so the needs of the people of Iran in matters of law are limited to the business of government, which, by reason of universal accidents, has become separated from Shari'a. . . .Now the people have thrown out the law of the Prophet and have set up their own law instead.[22]

He believed that the ruler was accountable to no institution other than God and people have no right to limit the powers or question the conduct of the King. He declared that those who supported democratic form of government were faithless and corrupt, and apostates.[23][24] He hated the idea of female education and said that girls schools were brothels.[25] Alongside his vicious propaganda against women education, he also opposed allocation of funds for modern industry, modern ways of governance, equal rights for all citizens irrespective of their religion and freedom of press. He believed that people were cattle, but paradoxically, he wanted to "awaken the muslim brethren".[26]

Ironically, Nouri had close connections to the foreigners whose cultural contamination he preached against. Historian Ervand Abrahamian writes,

Shayh Nouri had been on good terms with the Russians since the turn of the century. He had refused to support the early bazaar protests against the Europeans in charge of collecting customs dues. He had caused a major scandal in 1905 by endorsing the sale of a cemetery to the Russians for the construction of their bank -- the inadvertent exhuming of bodies had triggered street protests. He had organized an anticonstitutionalist rally in June 1907 after obtaining funds from the same Russian bank.[27]

The anti-democracy clerics incited violence and one such cleric said that getting in the proximity of the parliament was a bigger sin than adultery, robbery and murder.[28] In Zanjan, Mulla Qurban Ali Zanjani mobilized a force of six hundred thugs who looted shops of pro-democracy merchants and took hold of the city for several days and killed the representative Sa'd al-Saltanih.[29] Nouri himself recruited mercenaries from criminal gangs to harass the supporters of democracy. On December 22, 1907, Nouri led a mob towards Tupkhanih Square and attacked merchants and looted stores.[30] Nouri's ties to the court of monarchy and landlords reinforced his fanaticism. He even contacted the Russian embassy for support and his men delivered sermons against democracy in mosques, resulting in chaos.[31] Akhund Khurasani was consulted on the matter and in a letter dated December 30, 1907, the three Marja's said:

چون نوری مخل آسائش و مفسد است، تصرفش در امور حرام است.

محمد حسین (نجل) میرزا خلیل، محمد کاظم خراسانی، عبدالله مازندرانی [33]

"Because Nouri is causing trouble and sedition, his interfering in any affair is forbidden."

— Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

However, Nouri continued his activities and a few weeks later Akhund Khurasani and his fellow Marja's argued for his expulsion from Tehran:[34]

رفع اغتشاشات حادثه و تبعید نوری را عاجلاً اعلام.

الداعی محمد حسین نجل المرحوم میرزا خلیل، الداعی محمد کاظم الخراسانی، عبدالله المازندرانی [35]

"Restore peace and expel Nouri as quickly as possible."

— Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

One major concern of Akhund Khurasani and other Marja's was to familiarize the public with the ideas of a democratic nation-state and modern constitution. Akhund Khurasani asked Iranian scholars to deliver sermons on the subject to clarify doubts seeded by Nuri and his comrades. Hajj Shaikh Muhammad Va'iz Isfahani, a skillful orator of Tehran, made concerted efforts to educate the masses.[36] Another scholar, Sayyid Jamal al-Din Va'iz continuously refuted Nuri's propaganda and said that religious tyranny was worse than the temporal tyranny as the harm that the corrupt clerics inflict upon Islam and Muslims is worse. He advised the Shia masses to not pay attention to everyone with a turban on his head, rather they should listen to the guidelines of the sources of emulation in Najaf. [37] Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, the enlightened Thiqa tul-Islam from Tabriz, wrote a treatise "Lalan"(Persian: لالان).[38] He opposed Nuri saying that only the opinion of the sources of emulation is worthy of consideration in the matters of faith.[39] He wrote:

He who wins his own soul, protects his religion, is against following his desires and is obedient to the command of his Master; that is the person whom the people should take as their model.[38]

And

Let us consider the idea that the constitution is against Sharia law: all oppositions of this kind are in vain because the hujjaj al-islam of the atabat, who are today the models (marja) and the refuge (malija) of all Shiites, have issued clear fatwas that uphold the necessity of the Constitution. Aside from their words, they have also shown this by their actions. They see in Constitution the support for splendour of Islam.[38]

He firmly opposed the idea of a supervisory committee of Tehran's clerics censoring the conduct of the parliament, and said that:

this delicate subject shall be submitted to the atabat, . . . we don't have the right to entrust government to a group of four or five mullahs from Tehran.[38]

Nouri said that an imitator should not follow the jurist if he supports democracy:

If a thousand jurists write that this parliament is founded on the command to do good and prohibit evil . . . then you are witness that this is not the case and they have erred . . . (exactly as if they were to say) this animal is a sheep, and you know it is a dog, you have to say, 'You are mistaken, it is unclean'.[40]

As far as Nouri's argument was concerned, Akhund Khurasani refuted it in a light tone by saying that he supported the "parliament at Baharistan Square", questioning the legitimacy of Nouri's assembly at Shah Abdul Azim shrine and their right to decide for the people.[41]

Occultation of Imam in Shia Islam refers to a belief that Mahdi, a cultivated male descendant of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, has already been born and subsequently went into occultation, from which he will one day emerge with Jesus and establish global justice. Akhund Khurasani and his colleagues theorized a model of religious secularity in the absence of Imam, that still prevails in Shia seminaries.[42] In absence of the ideal ruler, that is Imam al-Mahdi, democracy was the best available option.[43] Akhund Khurasani considers opposition to constitutional democracy as hostility towards the twelfth Imam.[44] He declared his full support for constitutional democracy and announced that objection to "foundations of constitutionalism" was un-Islamic.[29] According to Akhund, "a rightful religion imposes conditions on the actions and behavior of human beings", which stem from either holy text or logical reasoning, and these constraints are essentially meant to prevent despotism.[45] He said that an Islamic system of governance can not be established without the infallible Imam leading it. Thus the clergy and modern scholars have concluded that a proper legislation can help reduce the state tyranny and maintain peace and security. Responding to a question about Nouri's arguments, Akhund said:[46]

Persian: سلطنت مشروعه آن است کہ متصدی امور عامه ی ناس و رتق و فتق کارهای قاطبه ی مسلمین و فیصل کافه ی مهام به دست شخص معصوم و موید و منصوب و منصوص و مأمور مِن الله باشد مانند انبیاء و اولیاء و مثل خلافت امیرالمومنین و ایام ظهور و رجعت حضرت حجت، و اگر حاکم مطلق معصوم نباشد، آن سلطنت غیرمشروعه است، چنان کہ در زمان غیبت است و سلطنت غیرمشروعه دو قسم است، عادله، نظیر مشروطه کہ مباشر امور عامه، عقلا و متدینین باشند و ظالمه و جابره است، مثل آنکه حاکم مطلق یک نفر مطلق العنان خودسر باشد. البته به صریح حکم عقل و به فصیح منصوصات شرع «غیر مشروعه ی عادله» مقدم است بر «غیرمشروعه ی جابره». و به تجربه و تدقیقات صحیحه و غور رسی های شافیه مبرهن شده که نُه عشر تعدیات دوره ی استبداد در دوره ی مشروطیت کمتر میشود و دفع افسد و اقبح به فاسد و به قبیح واجب است.[47]

English: "According to Shia doctrine, only the infallible Imam has the right to govern, to run the affairs of the people, to solve the problems of the Muslim society and to make important decisions. As it was in the time of the prophets or in the time of the caliphate of the commander of the faithful, and as it will be in the time of the reappearance and return of the Mahdi. If the absolute guardianship is not with the infallible then it will be a non-islamic government. Since this is a time of occultation, there can be two types of non-islamic regimes: the first is a just democracy in which the affairs of the people are in the hands of faithful and educated men, and the second is a government of tyranny in which a dictator has absolute powers. Therefore, both in the eyes of the Sharia and reason what is just prevails over the unjust. From human experience and careful reflection it has become clear that democracy reduces the tyranny of state and it is obligatory to give precedence to the lesser evil."

— Muhammad Kazim Khurasani

As "sanctioned by sacred law and religion", Akhund believes, a theocratic government can only be formed by the infallible Imam.[48] Aqa Buzurg Tehrani also quoted Akhund Khurasani saying that if there was a possibility of establishment of a truly legitimate Islamic rule in any age, God must end occultation of the Imam of Age. Hence, he refuted the idea of absolute guardianship of jurist.[49] [50] Therefore, according to Akhund, Shia jurists must support the democratic reform. Akhund prefers collective wisdom (Persian: عقل جمعی) over individual opinions, and limits the role of jurist to provide religious guidance in personal affairs of a believer.[51] He defines democracy as a system of governance that enforces a set of "limitations and conditions" on the head of state and government employees so that they work within "boundaries that the laws and religion of every nation determines". Akhund believes that modern secular laws complement traditional religion. He asserts that both religious rulings and the laws outside the scope of religion confront "state despotism".[52] Constitutionalism is based on the idea of defending the "nation's inherent and natural liberties", and as absolute power corrupts, a democratic distribution of power would make it possible for the nation to live up to its full potential.[53]

His close associate and student, who later rose to the rank of Marja, Muhammad Hussain Naini, wrote a book, "Tanbih al-Ummah wa Tanzih al-Milla", (Persian: تنبیه الامه و تنزیه المله), to counter the propaganda of Nuri group.[54] [48] [55] He maintained that in the absence of Imam Mahdi, all governments are doomed to be imperfect and unjust, and therefore people had to prefer the bad over the worse. Hence, the constitutional democracy was the best option to help improve the condition of the society as compared to absolutism, and run the worldly affairs with consultation and better planning. he saw the elected members of the parliament as representatives of the people, not deputies of the Imam, hence they didn't need a religious justification for their authority. He said that both the "tyrannical Ulema" and the radical societies who promoted majoritarianism were a threat to both Islam and democracy. The people should avoid the destructive, corrupt and divisive forces and maintain national unity.[54][56] He devoted large section of his book to definition and condemnation of religious tyranny. He then went on to defend people's freedom of opinion and expression, equality of all citizens in eyes of the nation-state regardless of their religion, separation of the legislative, executive and judicial powers, accountability of the King, people's right to share power.[54] [57] Another student of Akhund Khurasani who too raised to the rank of Marja, Shaykh Isma'il Mahallati, wrote a treatise "al-Liali al-Marbuta fi Wajub al-Mashruta"(Persian: اللئالی المربوطه فی وجوب المشروطه).[48] In his view, during the occultation of the twelfth Imam, the governments can either be imperfectly just or oppressive. Since it was duty of a believer to actively fight injustice, it was necessary to strengthen democratic process.[58] he insisted on the need for reforming the economic system, modernizing the military, installing a functional education system, and guaranteeing the rights of civilians.[58] He said:

'constitutional' and 'oppressive' are both only adjectives that describe different governments. If the sovereign appropriates all power to himself, for his own personal benefit, then the government is a tyrannical one; if, on the other hand, the sovereign's power is limited by the people, then the government is constitutional. This distinction has nothing to do with religion. Whatever the religion of the inhabitants of a nation, whether they be monotheistic or polytheistic, Muslims or unbelievers, their government could be either constitutional or tyrannical.[51]

Nouri interpreted Sharia in a self-serving and shallow way, unlike Akhund Khurasani who, as a well received source of emulation, viewed the adherence to religion in a society beyond one person or one interpretation.[59] While Nouri confused Sharia with written constitution of a modern society, Akhund Khurasani understood the difference and the function of the two.[10]

Nouri tried to get support from Ayatullah Kazim Yazdi, another prominent Marja of Najaf. He was apolitical, and therefore during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, he stayed neutral most of the times and seldom issued any political statement.[60] Contrary to Akhund Khorasani, he thought that Usulism did not offer the liberty to support constitutional politics. In his view, politics was beyond his expertise and therefore he avoided taking part in it.[61] While Akhund Khorasani was an eminent Marja' in Najaf, many imitators prayed behind Kazim Yazdi too, as his lesson on rulings (fight) was famous.[62] In other words, both Mohammad Kazem and Khorasani had constituted a great Shia school in Najaf although they had different views in politics at the same time.[63] However, he was not fully supportive of Fazlullah Nouri and Muhammad Ali Shah, therefore, when parliament asked him to review the final draft of constitution, he suggested some changes and signed the document.[64] He said that modern industries were permissible unless explicitly prohibited by Sharia.[65] He also agreed with teaching of modern sciences, and added that the state should not intervene the centers of religious learning (Hawza). He wasn't against formation of organizations and societies that do not create chaos, and in this regard there was no difference between religious and non-religious organizations.[65] In law-making, unlike Nouri, he separated the religious (Sharia) and public law (Urfiya). His opinion was that the personal and family matters should be settled in religious courts by jurists, and the governmental affaris and matters of state should be taken care of by modern judiciary. Parliament added article 71 and 72 into the constitution based on his opinions.[66] Ayatullah Yazdi said that as long as modern constitution did not force people to do what was forbidden by Sharia and refrain from religious duties, there was no reason to oppose democratic rule and the government had the right to prosecute wrong doers.[67] The Revolutional Tribunal declared him guilty of incited mobs against the constitutionalists and issuing fatwas declaring parliamentary leaders "apostates", "atheists," "secret Freemasons" and koffar al-harbi (warlike pagans) whose blood ought to be shed by the faithful.[6][1]

Thiqat-ul-Islam Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi showed unwavering support for modern knowledge and technology, and saw it necessary means to avoid colonial takeover of Iran. He said:

is it not necessary to acquire the same material and moral weapons as the adversary, as recommended by this noble verse: 'Make ready for them all you can of force and horse tethered'? For the moment, these are what give rise to the dominance and the influence of the adversary. Is it not necessary for schools to be built? In accordance with this verse: 'Be hostile to anyone who is hostile towards you, in the measure in which he is hostile to you', we must acquire wealth, the technologies necessary for daily life, political science and knowledge. These are what will allow us to no longer be dependent on foreigners, and this dependence is the primary means by which infidels dominate the land of Islam. Therefore, we must fight them using the same methods that they have used against us.[68]

Akhund Khurasani believed that it was obligatory for believers to attain necessary level of education and skill to be able to protect national and religious interests.[69] He saw democracy as a means to efficient governance that would bring prosperity and prevent colonial influence. He kept pressing for the need for modern schools to provide education to all children, modern economics, establishment of a national bank and industrialization. He believed that modernity would prevent savagery. After describing the need for modern reforms, he said:[70]

Persian: متمرد از آن یا جاهل و احمق است یا معاند دین حنیف اسلام.[71]

"Those who do not accept this fact are either ignorant subordinates or adversaries of the noble Muslim religion."

— Muhammad Kazim Khurasani

He emphasized on the need for establishment of nation-wide school system that would teach modern sciences and operate according to Islamic ethics.[70]

Execution

editNouri allied himself with the new Shah, Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar, who, with the assistance of Russian troops staged a coup against the Majlis (parliament) in 1907. In 1909, however, constitutionalists marched onto Tehran (the capital of Iran). Nouri was arrested, tried and found guilty of "sowing corruption and sedition on earth,"[1] and in July 1909, Nouri was hanged as a traitor. According to the Islamic Revolution Document Centre, Nouri might have been saved by taking refuge in the Russian Embassy or putting the Russian flag above his house, but his principles would not allow it. He allegedly told his acolytes: "Islam never goes under the banner of evasion ... Is it allowable that I go under the banner of evasion after 70 years of struggle for the sake of Islam?" Then, (according to the Islamic Revolution Document Centre) "he demanded his companions to empty the house in order to be immune from any harm."[73] He is described as a man of conviction and courage for resisting rather than fleeing the Constitutionalists's armed attack on his locale which led to his arrest and execution.[4]

Influence

editAccording to Ali Abolhassani (Monzer), author of Sheikh Fazlolah Nouri and the Chronological School of Constitutionalism, "The study of constitutionality is not possible without the study of intellectual and political attitudes of Hajj Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri. He has been influential in various phases of the process and if constitutionality is the first real ground for the serious confrontation between religion and modernism, in those days, Sheikh sided for the defense of religion and paid a great expense for it..."[74] The Islamic Revolution Document Centre quotes author Jalal Al-e-Ahmad as calling Nouri an "honourable man", and comparing his hanged corpse to "the flag of domination of occidentosis raised above the country after 200 years of struggle".[75][73]

According to Afshin Molavi, "Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri's heirs - Iran's ruling conservative clerics - have taken up his cause in the early 21st century" in the fight against democratic reform movement.[76] He is "hailed as a champion who had fought against corrupt Western values", in Tehran a major expressway is named after him, and features "a huge mural commemorating him".[5]

His grandson, Noureddin Kianouri, was an architect and high-ranking official in the Iranian communist party; he was arrested in 1983, tortured, and forced to deliver a televised confession.[77] He died in 1999.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Abrahamian, Ervand, Tortured Confessions by Ervand Abrahamian, University of California Press, 1999 p. 24

- ^ a b Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.96

- ^ Molavi, Afshin (2002). Persian Pilgrimages: Journeys Across Iran. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 192-. ISBN 978-0-393-05119-3. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

The Tehran billboard of Nouri, erected shortly after the revolution by the Islamic Republic of Iran, presents a different story, one of martyrdom. ... The message is not subtle: the Unjustly hanged Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri, ... was martyred for his defense of Islam against democracy and representative government.

- ^ a b Moin, Baqir (1999). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. I.B.Tauris. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-85043-128-2.

- ^ a b Basmenji, Kaveh (2005). Tehran Blues: Youth Culture in Iran. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-515-1.

- ^ a b Taheri, Amir, The Spirit of Allah by Amir Adler and Adler (1985), pp. 45–6

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.95-6

- ^ a b Farzaneh 2015, pp. 195.

- ^ a b Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- ^ a b Farzaneh 2015, p. 201.

- ^ Jahanbegloo, Ramin (2004). Iran: Between Tradition and Modernity. Lexington Books. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7391-0530-6.

- ^ a b c Martin, Vanessa. "NURI, Ḥājj Shaikh FAŻL-ALLĀH – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- ^ Cleveland, William L.; Bunton, Martin (2013). A history of the modern Middle East (Fifth ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8133-4833-9.

- ^ a b Farzaneh 2015, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Bayat, Mangol (1991). Iran's first revolution: Shi'ism and the constitutional revolution of 1905-1909. Studies in Middle Eastern history. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-506822-1. OCLC 1051306470. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ محسن کدیور، "سیاست نامه خراسانی"، ص۱۶۹، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- ^ Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 196.

- ^ Martin 1986, p. 182.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 197.

- ^ Martin 1986, p. 183.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 198.

- ^ Martin 1986, p. 185.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 199.

- ^ Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- ^ Abrahamian, Khomeinism, 1993: p.95

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 193.

- ^ a b Farzaneh 2015, pp. 160.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, p. 205.

- ^ Bayat, Mangol (1991). "Iran's First Revolution: Shi'ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909". Studies in Middle Eastern History. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-19-506822-1.

- ^ Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (2015). "The Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani". Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-8156-5311-0.

- ^ محسن کدیور، "سیاست نامه خراسانی"، ص۱۷۷، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- ^ Hermann 2013.

- ^ محسن کدیور، "سیاست نامه خراسانی"، ص١٨٠، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 156, 164–166.

- ^ Mangol 1991, pp. 188.

- ^ a b c d Hermann 2013, p. 439.

- ^ Hermann 2013, p. 438.

- ^ Martin 1986, p. 191.

- ^ Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (2015). "The Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani". Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8156-5311-0.

- ^ Ghobadzadeh, Naser (December 2013). "Religious secularity: A vision for revisionist political Islam". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 39 (10): 1005–1027. doi:10.1177/0191453713507014. ISSN 0191-4537. S2CID 145583418.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 152.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 159.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 161.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 162.

- ^ محسن کدیور، "سیاست نامه خراسانی"، ص ۲۱۴-۲۱۵، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- ^ a b c Hermann 2013, pp. 434.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 220.

- ^ آخوند خراسانی، حاشیة المکاسب، ص 92 تا 96، وزارت ثقافت وارشاد اسلامی، تہران، ۱۴۰۶ ہجری قمری

- ^ a b Hermann 2013, p. 436.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 166.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 167.

- ^ a b c Nouraie 1975.

- ^ Mangol 1991, p. 256.

- ^ Mangol 1991, p. 257.

- ^ Mangol 1991, p. 258.

- ^ a b Hermann 2013, pp. 435.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 200.

- ^ Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, p. 214.

- ^ Mottahedeh, R. (2014). The Mantle of the Prophet. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-738-5. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Hann, G.; Dabrowska, K.; Greaves, T.T. (2015). Iraq: The ancient sites and Iraqi Kurdistan. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-84162-488-4. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, p. 215.

- ^ a b Farzaneh 2015, p. 216.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, p. 217.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, p. 218.

- ^ Hermann 2013, pp. 442, 443.

- ^ Farzaneh 2015, pp. 178.

- ^ a b Hermann 2013, pp. 442.

- ^ kadivarad33 (6 August 2006). "سیاست نامه خراسانی". محسن کدیور (in Persian). Retrieved 26 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Hermann 2013, p. 440.

- ^ a b "The martyrdom of Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri, the leader of Iran's constitutional movement". Islamic Revolution Document Center. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Sheikh Fazlolah Nouri and the Chronological School of Constitutionalism". Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ On the Services and Treasons of Intellectuals, Jalal Al-e-Ahmad

- ^ Molavi, Afshin (20 April 2001). "Popular Frustration in Iran Simmers as Conservative Crackdown Continue". Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand (1999). Tortured Confessions: Prisons and Public Recantations in Modern Iran }. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92290-7.

Bibliography

edit- Abrahamian, Ervand (1993). Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. California: University of California Press. pp. 92–97. ISBN 0520081730. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Martin, V. A. (April 1986). "The Anti-Constitutionalist Arguments of Shaikh Fazlallah Nuri". Middle Eastern Studies. 22 (2): 181–196. doi:10.1080/00263208608700658. JSTOR 4283111.

- Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (March 2015). Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3388-4. OCLC 931494838.

- Hermann, Denis (1 May 2013). "Akhund Khurasani and the Iranian Constitutional Movement". Middle Eastern Studies. 49 (3): 430–453. doi:10.1080/00263206.2013.783828. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 23471080. S2CID 143672216.

- Nouraie, Fereshte M. (1975). "The Constitutional Ideas of a Shi'ite Mujtahid: Muhammad Husayn Na'ini". Iranian Studies. 8 (4): 234–247. doi:10.1080/00210867508701501. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 4310208.

- Mangol, Bayat (1991). Iran's First Revolution: Shi'ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506822-1.

Further reading

edit- Ahmad Kasravi, Tārikh-e Mashruteh-ye Iran (تاریخ مشروطهٔ ایران) (History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution), in Persian, 951 p. (Negāh Publications, Tehran, 2003), ISBN 964-351-138-3. Note: This book is also available in two volumes, published by Amir Kabir Publications in 1984. Amir Kabir's 1961 edition is in one volume, 934 pages.

- Ahmad Kasravi, History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution: Tārikh-e Mashrute-ye Iran, Volume I, translated into English by Evan Siegel, 347 p. (Mazda Publications, Costa Mesa, California, 2006). ISBN 1-56859-197-7