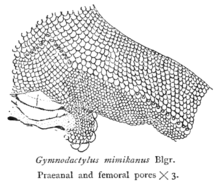

Femoral pores are a part of a holocrine secretory gland found on the inside of the thighs of certain lizards and amphisbaenians which releases pheromones to attract mates or mark territory. In certain species only the male has these pores and in other species, both sexes have them, with the male's being larger.[1] Femoral pores appear as a series of pits or holes within a row of scales on the ventral portion of the animal's thigh.

Femoral pores are present in all genera in the families Cordylidae, Crotaphytidae, Hoplocercidae, Iguanidae, Phrynosomatidae, and Xantusiidae.[1] They are absent in all genera in the Anguidae, Chamaeleonidae, Dibamidae, Helodermatidae, Scincidae, Xenosauridae, and Varanidae families.[1] They are present in other lizards and amphisbaenians quite variably, some geckoes, Phelsuma, for example have these pores, others in the same family do not.[1]

In the desert iguana (Dipsosaurus dorsalis), the waxy lipids released from the femoral pores absorb ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths making them visible to species which can detect UV light.[3] According to tests performed on the Green iguana, the variation in the chemicals released by the femoral pores can help to determine age, sex, and individual identity of the animal in question.[4] Male leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius), actually taste the secretions by flicking their tongues, if a male determines the other gecko in question is a male, the two will fight.[5]

In certain species such as geckoes, the females lack femoral pores altogether. In most families of lizards that have femoral pores, notably the iguanids, both sexes have femoral pores, but the males tend to be much larger than females of the same size and age.[4] In these instances they are used as a marker for sexual dimorphism.[4]

The number of femoral pores varies considerably among species.[2] For example, the number of pores in male lizards of the family Lacertidae can range between zero (e.g. Meroles anchietae) and 32 (e.g. Gallotia galloti) per limb.[6] Also, shrub-climbing species tend to have fewer femoral pores than species inhabiting other substrates (such as sandy and rocky substrate), suggesting a role of the environment on the evolution of the chemical signaling apparatus in lacertid lizards.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Pianka, Eric; Vitt, Laurie (2003). Lizards Windows to the Evolution of Diversity. University of California Press. pp. 92. ISBN 978-0-520-24847-2.

- ^ a b Baeckens, Simon (9 July 2015). "Evolution and role of the follicular epidermal gland system in non-ophidian squamates". Amphibia-Reptilia. 36 (3): 185–206. doi:10.1163/15685381-00002995. hdl:10067/1274960151162165141.

- ^ Alberts, Allison C. (1990). "Chemical Properties of Femoral Gland Secretions in the Desert Iguana, Dipsosaurus dorsalis". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 16 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1007/BF01021264. PMID 24264892. S2CID 25662804.

- ^ a b c Alberts, Allison C.; Thomas R. Sharp; Dagmar I. Werner; Paul J. Weldon (1992). "Seasonal variation of lipids in femoral gland secretions of male green iguanas (Iguana iguana)". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 18 (5): 703–712. doi:10.1007/BF00994608. PMID 24253964. S2CID 35393876.

- ^ Mason, R.T. (1992). "Reptilian pheromones". Biology of the Reptilia. 18: 114–228.

- ^ a b Baeckens, Simon (January 2015). "Chemical signalling in lizards: an interspecific comparison of femoral pore numbers in Lacertidae". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 114: 44–57. doi:10.1111/bij.12414. hdl:10067/1205040151162165141.