The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Imperial German Army back, undoing its gains from the German spring offensive (21 March – 18 July).

| Hundred Days Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War I | |||||||

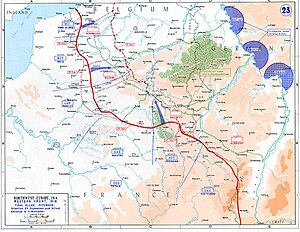

Allied gains in late 1918 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Strength on 11 November 1918:[3] |

Strength on 11 November 1918:[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

18 July – 11 November: 1,070,000[4] |

18 July – 11 November: 100,000+ killed 685,733 wounded 386,342 captured 6,700 artillery pieces Breakdown 2,500 killed 5,000 captured 10,000 wounded | ||||||

The Germans retreated to the Hindenburg Line, but the Allies broke through the line with a series of victories, starting with the Battle of St Quentin Canal on 29 September. The offensive led directly to the Armistice of 11 November 1918 which ended the war with an Allied victory. The term "Hundred Days Offensive" does not refer to a battle or strategy, but rather the rapid series of Allied victories.

Background

editThe German spring offensive on the Western Front had begun on 21 March 1918 with Operation Michael and had petered out by July. The German Army had advanced to the River Marne, but failed to achieve their aim of a victory that would decide the war. When the German Operation Marne-Rheims ended in July, the Allied supreme commander, Ferdinand Foch, ordered a counter-offensive, which became known as the Second Battle of the Marne. The Germans, recognizing their untenable position, withdrew from the Marne to the north. For this victory, Foch was granted the title Marshal of France.

After the Germans had lost their forward momentum, Foch considered the time had arrived for the Allies to return to the offensive. The American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under United States General John J. Pershing had arrived in France in large numbers and had reinvigorated the Allied armies with its extensive resources.[8]: 472 [need quotation to verify] Pershing was keen to use his army as an independent force. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had been reinforced by large numbers of troops returned from the Sinai and Palestine campaign and from the Italian front, and by replacements previously held back in Britain by Prime Minister David Lloyd George.[8]: 155

The military planners considered a number of proposals. Foch agreed to a proposal by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of the BEF, to strike on the River Somme, east of Amiens and south-west of the site of the 1916 Battle of the Somme, to force the Germans away from the vital Amiens–Paris railway.[8]: 472 The Somme was chosen because it remained the boundary between the BEF and the French armies, along the Amiens–Roye road, allowing the two armies to cooperate. The Picardy terrain provided a good surface for tanks, unlike in Flanders, and the defences of the German 2nd Army under General Georg von der Marwitz were relatively weak, having been subjected to continual raiding by the Australians in a process termed peaceful penetration.

Battles

editAdvance in Picardy

editBattle of Amiens

editThe Battle of Amiens (with the French attack on the southern flank called the Battle of Montdidier) opened on 8 August, with an attack by more than 10 Allied divisions—Australian, Canadian, British and French forces—with more than 500 tanks.[8]: 497 The mastermind of the plan was the Australian Lieutenant General John Monash.[9][10] Through careful preparation, the Allies achieved surprise.[11]: 20, 95 [12] The attack, led by the British Fourth Army, broke through the German lines, and tanks attacked German rear positions, sowing panic and confusion. By the end of the day, a gap 15 mi (24 km) wide had been created in the German line south of the Somme.[13] The Allies had taken 17,000 prisoners and 339 guns. Total German losses were estimated to be 30,000 men, while the Allies had suffered about 6,500 killed, wounded and missing. The collapse in German morale led Erich Ludendorff to dub it "the Black Day of the German Army".[11]: 20, 95

The advance continued for three more days but without the spectacular results of 8 August, since the rapid advance outran the supporting artillery and ran short of supplies.[14] During those three days, the Allies had managed to gain 12 mi (19 km). Most of this was taken on the first day as the arrival of German reinforcements after this slowed the Allied advance.[15] On 10 August, the Germans began to pull out of the salient that they had managed to occupy during Operation Michael in March, back towards the Hindenburg Line.[16]

Somme

editOn 15 August, Foch demanded that Haig continue the Amiens offensive, even though the attack was faltering as the troops outran their supplies and artillery and German reserves were being moved to the sector[citation needed]. Haig refused and prepared to launch a fresh offensive by the Third Army at Albert (the Battle of Albert), which opened on 21 August.[8]: 713–4 The offensive was a success, pushing the German 2nd Army back over a 34 mi (55 km) front. Albert was captured on 22 August.[17] The attack was widened on the south, by the French Tenth Army starting the Second Battle of Noyon on 17 August, capturing the town of Noyon on 29 August.[17] On 26 August, to the north of the initial attack, the First Army widened the attack by another 7 mi (11 km) with the Second Battle of Arras of 1918. Bapaume fell on 29 August (during the Second Battle of Bapaume).

Advance to the Hindenburg Line

editWith the front line broken, a number of battles took place as the Allies forced the Germans back to the Hindenburg Line. East of Amiens (after the Battle of Amiens), with artillery brought forward and munitions replenished, the Fourth Army also resumed its advance, with the Australian Corps crossing the Somme River on the night of 31 August, breaking the German lines during the Battle of Mont Saint-Quentin.[18] On 26 August, to the north of the Somme, the First Army widened the attack by another 7 mi (11 km) with the Second Battle of Arras of 1918, which includes the Battle of the Scarpe (1918) (26 August) and the Battle of Drocourt-Queant Line (2 September).[19]

South of the BEF, the French First Army approached the Hindenburg Line on the outskirts of St. Quentin during the Battle of Savy-Dallon (10 September),[20]: 128–9 and the French Tenth Army approached the Hindenburg Line near Laon during the Battle of Vauxaillon (14 September).[20]: 125 The British Fourth Army approached the Hindenburg Line along the St Quentin Canal, during the Battle of Épehy (18 September). By 2 September, the Germans had been forced back close to the Hindenburg Line from which they had launched their offensive in the spring.

Battles of the Hindenburg Line

editFoch planned a series of concentric attacks on the German lines in France (sometimes referred to as the Grand Offensive), with the various axes of advance designed to cut German lateral communications, intending that the success of an attack would enable the entire front line to be advanced.[11]: 205–6 The main German defences were anchored on the Hindenburg Line, a series of defensive fortifications stretching from Cerny on the Aisne river to Arras.[21] Before Foch's main offensive was launched, the remaining German salients west and east of the line were crushed at Havrincourt and St Mihiel on 12 September and at the Battle of Épehy and the Battle of the Canal du Nord on 27 September.[11]: 217

The first attack of the Grand Offensive was launched on 26 September by the French and the AEF in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (this offensive includes the battles of Somme-Py, Saint-Thierry, Montfaucon, and Chesne of 1 November). On 28 September, the Army Group under Albert I of Belgium (the Belgian Army, the British Second Army and the French Sixth Army), attacked near Ypres in Flanders (the Fifth Battle of Ypres). Both attacks made good progress initially but were then slowed by supply difficulties. The Grand Offensive involved attacking over difficult terrain, resulting in the Hindenburg Line not being broken until 17 October.[22]

On 29 September, the central attack on the Hindenburg Line commenced, with the British Fourth Army (with British, Australian and American forces)[23] attacking in the Battle of St Quentin Canal and the French First Army attacking fortifications outside St Quentin. By 5 October, the Allies had broken through the entire depth of the Hindenburg defences over a 19 mi (31 km) front.[20]: 123 General Rawlinson wrote, "Had the Boche [Germans] not shown marked signs of deterioration during the past month, I should never have contemplated attacking the Hindenburg line. Had it been defended by the Germans of two years ago, it would certainly have been impregnable…."

On 8 October, the First and Third British Armies broke through the Hindenburg Line at the Second Battle of Cambrai.[24] This collapse forced the German High Command to accept that the war had to be ended. The evidence of failing German morale also convinced many Allied commanders and political leaders that the war could be ended in 1918; previously, all efforts had been concentrated on building up forces to mount a decisive attack in 1919.

Subsequent operations

editThrough October, the German armies retreated through the territory gained in 1914. The Allies pressed the Germans back toward the lateral railway line from Metz to Bruges, which had supplied the front in northern France and Belgium for much of the war. As the Allied armies reached this line, the Germans were forced to abandon increasingly large amounts of heavy equipment and supplies, further reducing their morale and capacity to resist.[26]

The Allied and German armies suffered many casualties. Rearguard actions were fought during the Pursuit to the Selle (9 October), battles of Courtrai (14 October), Mont-d'Origny (15 October), the Selle (17 October), Lys and Escaut (20 October) (including the subsidiary battles of the Lys and of the Escaut), the Serre (20 October), Valenciennes (1 November), the Sambre (including the Second Battle of Guise) (4 November), and Thiérache (4 November), and the Passage of the Grande Honnelle (5 November), with fighting continuing until the Armistice took effect at 11:00 on 11 November 1918. The last soldier to die was Henry Gunther, one minute before the armistice came into effect.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Allied Commander

- ^ Commander of the French Army

- ^ Commander of Army Group Centre

- ^ Commander of Army Group Reserve

- ^ Commander of Army Group East

- ^ Commander of BEF

- ^ Chief of Imperial General Staff of the British Army

- ^ Commander of AEF

- ^ Commander of Army Group Flanders

- ^ Commander of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps

- ^ Divisional Commander of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps

- ^ Chief of the German Great General Staff

- ^ First Quartermaster General

- ^ First Quartermaster General

- ^ Commander of Army Group Gallwitz

- ^ Commander of Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria

- ^ Commander of Army Group German Crown Prince

- ^ Commander of Army Group Boehn

- ^ Commander of Army Group Albrecht

- ^ Also possessed 2,251 artillery pieces on the frontline out of the 3,500 total artillery pieces used by the Americans. Ayers p. 81

References

edit- ^ Caracciolo, M. Le truppe italiane in Francia. Mondadori. Milan 1929

- ^ Julien Sapori, Les troupes italiennes en France pendant la première guerre mondiale, éditions Anovi, 2008

- ^ a b Neiberg p. 95

- ^ a b Tucker 2014, p. 634.

- ^ Bond 1990, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Reid 2006, p. 448.

- ^ Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920, The War Office, pp. 356–357.

- ^ a b c d e Bean. The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Allied Offensive..

- ^ Monash, John (1920). "Chapter 5: The battle plan". The Australian Victories in France in 1918: the Battles of the Australian Army on the Western Front During the Final Year of the First World War. Black Inc. (published 2015). ISBN 9781863957458.

- ^ Perry, Roland (2004). Monash: The Outsider Who Won A War. Random House. pp. 532–539. ISBN 9780857982131.

- ^ a b c d Livesay, John Frederick Bligh (1919). Canada's Hundred Days: With the Canadian Corps from Amiens to Mons, Aug. 8 – Nov. 11, 1918. Toronto: Thomas Allen.

- ^ Christie, Norm M. (1999). For King and Empire: The Canadians at Amiens, August 1918. CEF Books. ISBN 1-896979-20-3.

- ^ Schreiber, Shane B. (2004) [1977]. Shock Army of the British Empire: the Canadian Corps in the last 100 days of the Great War. St. Catharines, ON: Vanwell. ISBN 1-55125-096-9.

- ^ Orgill, Douglas (1972). Armoured Onslaught: 8th August 1918. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-02608-X.

- ^ "Canada's Hundred Days". Canada: Veterans Affairs. 29 July 2004. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Dancocks, Daniel George (1987). Spearhead to Victory: Canada and the Great War. Hurtig. p. 294. ISBN 0-88830-310-6.

- ^ a b "History of the Great War – principal events timeline – 1918". Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Mont St Quentin – Peronne 31 August – 2 September 1918". Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "The Second Battles of Arras, 1918 – The Long, Long Trail". Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Hanotaux (1915). Histoire illustrée de la guerre de 1914.

- ^ Christie, Norm M. (2005) [1997]. The Canadians at Arras and the Drocourt–Queant Line, August–September, 1918. For King and Empire: A Social History and Battlefield Tour. CEF Books. ISBN 1-896979-43-2. OCLC 60369666.

- ^ "The German summer offensive and Soviet prospects", The Western Allies and Soviet Potential in World War II, Routledge, pp. 185–188, 27 March 2017, doi:10.4324/9781315682709-14, ISBN 9781315682709, retrieved 26 May 2022

- ^ Blair 2011, pp. 145–148.

- ^ Christie, Norm M. (1997). The Canadians at Cambrai and the Canal du Nord, August–September 1918. For King and Empire: A Social History and Battlefield Tour. CEF Books. ISBN 1-896979-18-1. OCLC 166099767.

- ^ Leonard P. Ayers, online The War with Germany: a statistical summary (1919) p 105

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (2007). Barbarism and Civilization: A History of Europe in Our Time. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-0-1987-3074-3.

Bibliography

edit- Bond, Brian (2007). The Unquiet Western Front, Britain's Role in Literature and History. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03641-2.

- Bean, Charles Edwin Woodrow (1942). The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Allied Offensive. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. VI. Angus and Robertson. OCLC 41008291. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Blair, Dale (2011). The Battle of Bellicourt Tunnel: Tommies, Diggers and Doughboys on the Hindenburg Line, 1918. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1848325876.

- Christie, Norm M. (1999). For King and Empire, The Canadians at Amiens, August 1918. CEF Books. ISBN 1-896979-20-3.

- Christie, Norm M. (2005). The Canadians at Arras and the Drocourt–Queant Line, August–September, 1918. CEF Books. ISBN 1-896979-43-2. OCLC 60369666.

- Christie, Norm M. (1997). The Canadians at Cambrai and the Canal du Nord, August–September 1918. CEF Books. ISBN 1-896979-18-1.

- Dancocks, Daniel George (1987). Spearhead to Victory: Canada and the Great War. Hurtig. ISBN 0-88830-310-6. OCLC 16354705.

- Hanotaux, Gabriel (1924). Histoire Illustrée de la Guerre de 1914 (in French). Vol. 17. Paris: Gounouilhou. OCLC 175115527.

- Livesay, John Frederick Bligh (1919). Canada's Hundred Days. Thomas Allen. OCLC 471474361.

- Lloyd, Nick (2013). Hundred Days: The End of the Great War. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-92006-8.

- Montgomery, Sir A. (1920). The Story of Fourth Army in the Battles of the Hundred Days, August 8th to November 11th, 1918. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 682022494. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Orgill, Douglas (1972). Armoured Onslaught: 8 August 1918. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-02608-X.

- Priestley, R. E. (1919). Breaking the Hindenburg Line: The Story of the 46th (North Midland) Division. London: Unwin. OCLC 671679006. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Reid, Walter (2006). Architect of Victory: Douglas Haig. Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1841585178.

- Schreiber, Shane B. (2004). Shock Army of the British Empire: The Canadian Corps in the Last 100 Days of the Great War. St.Catharine's, Ontario: Vanwell. ISBN 1-55125-096-9.

- Tucker, S. (2014). Zabecki, D. (ed.). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-598-84980-6.

External links

edit- Lloyd, Nicholas: Hundred Days Offensive, in: 1914–1918 – online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Maps of Europe Archived 1 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine during the Allied Hundred Days Offensive at omniatlas.com