An old master print (also spaced masterprint) is a work of art produced by a printing process within the Western tradition. The term remains current in the art trade, and there is no easy alternative in English to distinguish the works of "fine art" produced in printmaking from the vast range of decorative, utilitarian and popular prints that grew rapidly alongside the artistic print from the 15th century onwards. Fifteenth-century prints are sufficiently rare that they are classed as old master prints even if they are of crude or merely workmanlike artistic quality. A date of about 1830 is usually taken as marking the end of the period whose prints are covered by this term.

The main techniques used, in order of their introduction, are woodcut, engraving, etching, mezzotint and aquatint, although there are others. Different techniques are often combined in a single print. With rare exceptions printed on textiles, such as silk, or on vellum, old master prints are printed on paper. This article is concerned with the artistic, historical and social aspects of the subject; the article on printmaking summarizes the techniques used in making old master prints, from a modern perspective.

Many great European artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, and Francisco Goya, were dedicated printmakers. In their own day, their international reputations largely came from their prints, which were spread far more widely than their paintings. Influences between artists were also mainly transmitted beyond a single city by prints (and sometimes drawings), for the same reason. Prints therefore are frequently brought up in detailed analyses of individual paintings in art history. Today, thanks to colour photo reproductions, and public galleries, their paintings are much better known, whilst their prints are only rarely exhibited, for conservation reasons. But some museum print rooms allow visitors to see their collection, sometimes only by appointment, and large museums now present great numbers of prints online in very high-resolution enlargeable images.

History

editWoodcut before Albrecht Dürer

editThe oldest technique is woodcut, or woodblock printing, which was invented as a method for printing on cloth in China. This had reached Europe via the Islamic world before 1300, as a method of printing patterns on textiles. Paper arrived in Europe, also from China via Islamic Spain, slightly later, and was being manufactured in Italy by the end of the thirteenth century, and in Burgundy and Germany by the end of the fourteenth.[1] Religious images and playing cards are documented as being produced on paper, probably printed, by a German in Bologna in 1395.[2] However, the most impressive printed European images to survive from before 1400 are printed on cloth, for use as hangings on walls or furniture, including altars and lecterns. Some were used as a pattern to embroider over. Some religious images were used as bandages, to speed healing.[3]

The earliest print images are mostly of a high artistic standard, and were clearly designed by artists with a background in painting (on walls, panels or manuscripts). Whether these artists cut the blocks themselves, or only inked the design on the block for another to carve, is not known. During the fifteenth century the number of prints produced greatly increased as paper became freely available and cheaper, and the average artistic level fell, so that by the second half of the century the typical woodcut is a relatively crude image. The great majority of surviving 15th-century prints are religious, although these were probably the ones more likely to survive. Their makers were sometimes called "Jesus maker" or "saint-maker" in documents. As with manuscript books, monastic institutions sometimes produced, and often sold, prints. No artists can be identified with specific woodcuts until towards the end of the century.[4]

The little evidence we have suggests that woodcut prints became relatively common and cheap during the fifteenth century, and were affordable by skilled workers in towns. For example, what may be the earliest surviving Italian print, the "Madonna of the Fire", was hanging by a nail to a wall in a small school in Forlì in 1428. The school caught fire, and the crowd who gathered to watch saw the print carried up into the air by the fire, before falling down into the crowd. This was regarded as a miraculous escape and the print was carried to Forlì Cathedral, where it remains, since 1636 in a special chapel, displayed once a year. Like the majority of prints before approximately 1460, only a single impression (the term used for a copy of an old master print; "copy" is used for a print copying another print) of this print has survived.[5]

Woodcut blocks are printed with light pressure, and are capable of printing several thousand impressions, and even at this period some prints may well have been produced in that quantity. Many prints were hand-coloured, mostly in watercolour; in fact the hand-colouring of prints continued for many centuries, though dealers have removed it from many surviving examples. Italy, Germany, France and the Netherlands were the main areas of production; England does not seem to have produced any prints until about 1480. However prints are highly portable, and were transported across Europe. A Venetian document of 1441 already complains about cheap imports of playing cards damaging the local industry.[6]

Block-books were a very popular form of (short) book, where a page with both pictures and text was cut as a single woodcut. They were much cheaper than manuscript books, and were mostly produced in the Netherlands; the Art of Dying (Ars moriendi) was the most famous; thirteen different sets of blocks are known.[7] As a relief technique (see printmaking) woodcut can be printed easily together with movable type, and after this invention arrived in Europe about 1450 printers quickly came to include woodcuts in their books. Some book owners also pasted prints into prayer books in particular.[8] Playing cards were another notable use of prints, and French versions are the basis of the traditional sets still in use today.

By the last quarter of the century there was a large demand for woodcuts for book-illustrations, and in both Germany and Italy standards at the top end of the market improved considerably. Nuremberg was the largest centre of German publishing, and Michael Wolgemut, the master of the largest workshop there worked on many projects, including the gigantic Nuremberg Chronicle.[9] Albrecht Dürer was apprenticed to Wolgemut during the early stages of the project, and was the godson of Anton Koberger, its printer and publisher. Dürer's career was to take the art of the woodcut to its highest development.[10]

German engraving before Dürer

editEngraving on metal was part of the goldsmith's craft throughout the Medieval period, and the idea of printing engraved designs onto paper probably began as a method for them to record the designs on pieces they had sold. Some artists trained as painters became involved from about 1450–1460, although many engravers continued to come from a goldsmithing background. From the start, engraving was in the hands of the luxury tradesmen, unlike woodcut, where at least the cutting of the block was associated with the lower-status trades of carpentry, and perhaps sculptural wood-carving. Engravings were also important from very early on as models for other artists, especially painters and sculptors, and many works survive, especially from smaller cities, which take their compositions directly from prints. Serving as a pattern for artists may have been a primary purpose for the creation of many prints, especially the numerous series of apostle figures.

The surviving engravings, though the majority are religious, show a greater proportion of secular images than other types of art from the period, including woodcut. This is certainly partly the result of the relative survival rates—although wealthy fifteenth-century houses certainly contained secular images on walls (inside and outside), and cloth hangings, these types of image have survived in tiny numbers. The Church was much better at retaining its images. Engravings were relatively expensive and sold to an urban middle-class that had become increasingly affluent in the belt of cities that stretched from the Netherlands down the Rhine to Southern Germany, Switzerland and Northern Italy. Engraving was also used for the same types of images as woodcuts, notably devotional images and playing cards, but many seem to have been collected for keeping out of sight in an album or book, to judge by the excellent state of preservation of many pieces of paper over five hundred years old.[11]

Again unlike woodcut, identifiable artists are found from the start. The German, or possibly German-Swiss, Master of the Playing Cards was active by at least the 1440s; he was clearly a trained painter.[12] The Master E. S. was a prolific engraver, from a goldsmithing background, active from about 1450–1467, and the first to sign his prints with a monogram in the plate. He made significant technical developments, which allowed more impressions to be taken from each plate. Many of his faces have a rather pudding-like appearance, which reduces the impact of what are otherwise fine works. Much of his work still has great charm, and the secular and comic subjects he engraved are almost never found in the surviving painting of the period. Like the Otto prints in Italy, much of his work was probably intended to appeal to women.[13]

The first major artist to engrave was Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), who worked in southern Germany and was also a well-known painter. His father and brother were goldsmiths, so he may well have had experience with the burin from an early age. His 116 engravings have a clear authority and beauty and became well known in Italy as well as northern Europe, as well as much copied by other engravers. He also further developed engraving technique, in particular refining cross-hatching to depict volume and shade in a purely linear medium.[14]

The other notable artist of this period is known as the Housebook Master. He was a highly talented German artist who is also known from drawings, especially the Housebook album from which he takes his name. His prints were made exclusively in drypoint, scratching his lines on the plate to leave a much shallower line than an engraver's burin would produce; he may have invented this technique. Consequently, only a few impressions could be produced from each plate—perhaps about twenty—although some plates were reworked to prolong their life. Despite this limitation, his prints were clearly widely circulated, as many copies of them exist by other printmakers. This is highly typical of admired prints in all media until at least 1520; there was no enforceable concept of anything like copyright. Many of the Housebook Master's print compositions are only known from copies, as none of the presumed originals have survived — a very high proportion of his original prints are only known from a single impression. The largest collection of his prints is at Amsterdam; these were probably kept as a collection, perhaps by the artist himself, from around the time of their creation.[15]

Israhel van Meckenam was an engraver from the borders of Germany and the Netherlands, who probably trained with Master ES, and ran the most productive workshop for engravings of the century between about 1465 and 1503. He produced over 600 plates, most copies of other prints, and was more sophisticated in self-presentation, signing later prints with his name and town, and producing the first print self-portrait of himself and his wife. Some plates seem to have been reworked more than once by his workshop, or produced in more than one version, and many impressions have survived, so his ability to distribute and sell his prints was evidently sophisticated. His own compositions are often very lively, and take a great interest in the secular life of his day.[16]

The earliest Italian engravings

editPrintmaking in woodcut and engraving both appeared in Northern Italy within a few decades of their invention north of the Alps, and had similar uses and characters, though within significantly different artistic styles, and with from the start a much greater proportion of secular subjects. The earliest known Italian woodcut has been mentioned above. Engraving probably came first to Florence in the 1440s; Vasari typically claimed that his fellow-Florentine, the goldsmith and nielloist Maso Finiguerra (1426–64) invented the technique. It is now clear this is wrong, and there are now considered to be no prints as such that can be attributed to him on anything other than a speculative basis. He may never have made any printed engravings from plates, as opposed to taking impressions from work intended to be nielloed. There are a number of complex niello religious scenes that he probably executed, and may or may not have designed, which were influential for the Florentine style in engraving. Some paper impressions and sulphur casts survive from these. These are a number of paxes in the Bargello, Florence, plus one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York which depict scenes with large and well-organised crowds of small figures. There are also drawings in the Uffizi, Florence that may be by him.[17]

Florence

editWhere German engraving arrived into a still Gothic artistic world, Italian engraving caught the very early Renaissance, and from the start the prints are mostly larger, more open in atmosphere, and feature classical and exotic subjects. They are less densely worked, and usually do not use cross-hatching. From about 1460–1490 two styles developed in Florence, which remained the largest centre of Italian engraving. These are called (although the terms are less often used now) the "Fine Manner" and the "Broad Manner", referring to the typical thickness of the lines used. The leading artists in the Fine Manner are Baccio Baldini and the "Master of the Vienna Passion", and in the Broad Manner, Francesco Rosselli and Antonio del Pollaiuolo, whose only print was the Battle of the Nude Men (right), the masterpiece of 15th-century Florentine engraving.[18] This uses a new zigzag "return stroke" for modelling, which he probably invented.[19]

A chance survival is a collection of mostly rather crudely executed Florentine prints now in the British Museum, known as the Otto Prints after an earlier owner of most of them. This was probably the workshop's own reference set of prints, mostly round or oval, that were used to decorate the inside covers of boxes, primarily for female use. It has been suggested that boxes so decorated may have been given as gifts at weddings. The subject matter and execution of this group suggests they were intended to appeal to middle-class female taste; lovers and cupids abound, and an allegory shows a near-naked young man tied to a stake and being beaten by several women.[20]

Ferrara

editThe other notable early centre was Ferrara, from the 1460s, which probably produced both sets of the so-called "Mantegna Tarocchi" cards, which are not playing cards, but a sort of educational tool for young humanists with fifty cards, featuring the Planets and Spheres, Apollo and the Muses, personifications of the Seven liberal arts and the four Virtues, as well as "the Conditions of Man" from Pope to peasant.[21]

Mantegna in Mantua

editAndrea Mantegna who trained in Padua, and then settled in Mantua, was the most influential figure in Italian engraving of the century, although it is still debated whether he actually engraved any plates himself (a debate revived in recent years by Suzanne Boorsch). A number of engravings have long been ascribed to his school or workshop, with only seven usually given to him personally. The whole group form a coherent stylistic group and very clearly reflect his style in painting and drawing, or copy surviving works of his. They seem to date from the late 1460s onwards.[23]

The impact of Dürer

editIn the last five years of the fifteenth century, Dürer, then in his late twenties and with his own workshop in Nuremberg, began to produce woodcuts and engravings of the highest quality which spread very quickly through the artistic centres of Europe. By about 1505 most young Italian printmakers went through a phase of directly copying either whole prints or large parts of Dürer's landscape backgrounds, before going on to adapt his technical advances to their own style. Copying of prints was already a large and accepted part of the printmaking culture but no prints were copied as frequently as Dürer's.[24]

Dürer was also a painter, but few of his paintings could be seen except by those with good access to private houses in the Nuremberg area. The lesson of how he, following more spectacularly in the footsteps of Schongauer and Mantegna, was able so quickly to develop a continent-wide reputation very largely through his prints was not lost on other painters, who began to take much greater interest in printmaking.[25]

Italy 1500–1515

editFor a brief period a number of artists who began by copying Dürer made very fine prints in a range of individual styles. They included Giulio Campagnola, who succeeded in translating the new style Giorgione and Titian had brought to Venetian painting into engraving. Marcantonio Raimondi and Agostino Veneziano both spent some years in Venice before moving to Rome, but even their early prints show classicizing tendencies as well as Northern influence.[26] The styles of the Florentine Cristofano Robetta, and Benedetto Montagna from Vicenza are still based in Italian painting of the period, and are also later influenced by Giulio Campagnola.[27]

Giovanni Battista Palumba, once known as "Master IB with the Bird" from his monogram, was the major Italian artist in woodcut in these years, as well as an engraver of charming mythological scenes, often with an erotic theme.[28]

The rise of the reproductive print

editPrints copying prints were already common, and many fifteenth century prints must have been copies of paintings, but not intended to be seen as such, but as images in their own right. Mantegna's workshop produced a number of engravings copying his Triumph of Caesar (now Hampton Court Palace), or drawings for it, which were perhaps the first prints intended to be understood as depicting paintings—called reproductive prints. With an increasing pace of innovation in art, and of a critical interest among a non-professional public, reliable depictions of paintings filled an obvious need. In time this demand was almost to smother the old master print.[29]

Dürer never copied any of his paintings directly into prints, although some of his portraits base a painting and a print on the same drawing, which is very similar. The next stage began when Titian in Venice, and Raphael in Rome, almost simultaneously began to collaborate with printmakers to make prints to their designs. Titian at this stage worked with Domenico Campagnola and others on woodcuts, whilst Raphael worked with Raimondi on engravings, for which many of Raphael's drawings survive.[30] Rather later, the paintings done by the School of Fontainebleau were copied in etchings, apparently in a brief organised programme including many of the painters themselves.[31]

The Italian partnerships were artistically and commercially successful, and inevitably attracted other printmakers who simply copied paintings independently to make wholly reproductive prints. Especially in Italy, these prints, of greatly varying quality, came to dominate the market and tended to push out original printmaking, which declined noticeably from about 1530–1540 in Italy. By now some publisher/dealers had become important, especially Dutch and Flemish operators like Philippe Galle and Hieronymus Cock, developing networks of distribution that were becoming international, and much work was commissioned by them. The effect of the development of the print-selling trade is a matter of scholarly controversy, but there is no question that by the mid-century the rate of original printmaking in Italy had declined considerably from that of a generation earlier, if not as precipitously as in Germany.[32]

The North after Dürer

editAlthough no artist anywhere from 1500 to 1550 could ignore Dürer, several artists in his wake had no difficulty maintaining highly distinctive styles, often with little influence from him. Lucas Cranach the Elder was only a year younger than Dürer, but he was about thirty before he began to make woodcuts, in an intense Northern style reminiscent of Matthias Grünewald. He was also an early experimenter in the chiaroscuro woodcut technique. His style later softened, and took in the influence of Dürer, but he concentrated his efforts on painting, in which he became dominant in Protestant Germany, based in Saxony, handing over his very productive studio to his son at a relatively early age.[33]

Lucas van Leyden had a prodigious natural talent for engraving, and his earlier prints were highly successful, with an often earthy treatment and brilliant technique, so that he came to be seen as Dürer's main rival in the North. However, his later prints suffered from straining after an Italian grandeur, which left only the technique applied to far less dynamic compositions. Like Dürer, he had a "flirtation" with etching, but on copper rather than iron. His Dutch successors for some time continued to be heavily under the spell of Italy, which they took most of the century to digest.[34]

Albrecht Altdorfer produced some Italianate religious prints, but he is most famous for his very Northern landscapes of drooping larches and firs, which are highly innovative in painting as well as prints. He was among the most effective early users of the technique of etching, recently invented as a printmaking technique by Daniel Hopfer, an armourer from Augsburg. Neither Hopfer nor the other members of his family who continued his style were trained or natural artists, but many of their images have great charm, and their "ornament prints", made essentially as patterns for craftsmen in various fields, spread their influence widely.[35]

Hans Burgkmair from Augsburg, Nuremberg's neighbour and rival, was slightly older than Dürer, and had a parallel career in some respects, training with Martin Schongauer before apparently visiting Italy, where he formed his own synthesis of Northern and Italian styles, which he applied in painting and woodcut, mostly for books, but with many significant "single-leaf" (i.e. individual) prints. He is now generally credited with inventing the coloured chiaroscuro (coloured) woodcut.[36] Hans Baldung was Dürer's pupil, and was left in charge of the Nuremberg workshop during Dürer's second Italian trip. He had no difficulty in maintaining a highly personal style in woodcut, and produced some very powerful images.[37] Urs Graf was a Swiss mercenary and printmaker, who invented the white-line woodcut technique, in which his most distinctive prints were made.[38]

The Little Masters

editThe Little Masters is a term for a group of several printmakers, who all produced very small finely detailed engravings for a largely bourgeois market, combining in miniature elements from Dürer and from Marcantonio Raimondi, and concentrating on secular, often mythological and erotic, rather than on religious themes. The most talented were the brothers Bartel Beham and the longer-lived Sebald Beham. Like Georg Pencz, they came from Nuremberg and were expelled by the council for atheism for a period. The other principal member of the group was Heinrich Aldegrever, a convinced Lutheran with Anabaptist leanings, who was perhaps therefore forced to spend much of his time producing ornament prints.[39]

Another convinced Protestant, Hans Holbein the Younger, spent most of his adult career in England, then and for long after too primitive as both a market and in technical assistance to support fine printmaking. Whilst the famous blockcutter Hans Lützelburger was alive, he created from Holbein's designs the famous small woodcut series of the Dance of Death. Another Holbein series, of ninety-one Old Testament scenes, in a much simpler style, was the most popular of attempts by several artists to create Protestant religious imagery. Both series were published in Lyon in France by a German publisher, having been created in Switzerland.[40]

After the deaths of this very brilliant generation, both the quality and quantity of German original printmaking suffered a strange collapse; perhaps it became impossible to sustain a convincing Northern style in the face of overwhelming Italian productions in a "commoditized" Renaissance style. The Netherlands now became more important for the production of prints, which would remain the case until the late 18th century.[41]

Mannerist printmaking

editSome Italian printmakers went in a very different direction to either Raimondi and his followers, or the Germans, and used the medium for experimentation and very personal work. Parmigianino produced some etchings himself, and also worked closely with Ugo da Carpi on chiaroscuro woodcuts and other prints.[42]

Giorgio Ghisi was the major printmaker of the Mantuan school, which preserved rather more individuality than Rome. Much of his work was reproductive, but his original prints are often very fine. He visited Antwerp, a reflection of the power the publishers there now had over what was now a European market for prints. A number of printmakers, mostly in etching, continued to produce excellent prints, but mostly as a sideline to either painting or reproductive printmaking. They include Battista Franco, Il Schiavone, Federico Barocci and Ventura Salimbeni, who only produced nine prints, presumably because it did not pay. Annibale Carracci and his cousin Ludovico produced a few influential etchings, while Annibale's brother Agostino engraved. Both brothers influenced Guido Reni and other Italian artists of the full Baroque period in the next century.[43]

France

editThe Italian artists known as the School of Fontainebleau were hired in the 1530s by King Francis I of France to decorate his showpiece Chateau at Fontainebleau. In the course of the long project, etchings were produced, in unknown circumstances but apparently in Fontainebleau itself and mostly in the 1540s, mostly recording wall-paintings and plasterwork in the Chateau (much now destroyed). Technically they are mostly rather poor—dry and uneven—but the best powerfully evoke the strange and sophisticated atmosphere of the time. Many of the best are by Leon Davent to designs by Primaticcio, or Antonio Fantuzzi. Several of the artists, including Davent, later went to Paris and continued to produce prints there.[44]

Previously the only consistent printmaker of stature in France had been Jean Duvet, a goldsmith whose highly personal style seems halfway between Dürer and William Blake. His plates are extremely crowded, not conventionally well-drawn, but full of intensity; the opposite of the languorous elegance of the Fontainebleau prints, which were to have the greater effect on French printmaking. His prints date from 1520 to 1555, when he was seventy, and completed his masterpiece, the twenty-three prints of the Apocalypse.[45]

The Netherlands

editCornelius Cort was an Antwerp engraver, trained in Cock's publishing house, with a controlled but vigorous style, and excellent at depicting dramatic lighting effects. He went to Italy and in 1565 was retained by Titian to produce prints of his paintings (Titian having secured his "privileges" or rights to exclusively reproduce his own works). Titian took considerable trouble to get the effect he wanted; he said that Cort could not work from the painting alone, so he produced special drawings for him to use. Eventually, the results were highly effective and successful, and after Titian's death Cort moved to Rome, where he taught a number of the most successful printmakers of the next generation, notably Hendrik Goltzius, Francesco Villamena and Agostino Carracci, the last major Italian artist to resist the spread of etching.[46]

Goltzius, arguably the last great engraver, took Cort's style to its furthest point. Because of a childhood accident, he drew with his whole arm, and his use of the swelling line, altering the profile of the burin to thicken or diminish the line as it moved, is unmatched. He was extraordinarily prolific, and the artistic, if not the technical, quality of his work is very variable, but his finest prints look forward to the energy of Rubens, and are as sensuous in their use of line as he is in paint.[47]

At the same time Pieter Brueghel the elder, another Cort-trained artist, who escaped to paint, was producing prints in a totally different style; beautifully drawn but simply engraved. He only etched one plate himself, a superb landscape, the Rabbit Hunters, but produced many drawings for the Antwerp specialists to work up, of peasant life, satires, and newsworthy events.[48]

Meanwhile, numerous other engravers in the Netherlands continued to produce vast numbers of reproductive and illustrative prints of widely varying degrees of quality and appeal—the two by no means always going together. Notable dynasties, often publishers as well as artists, include the Wierix family, the Saenredams, and Aegidius Sadeler and several of his relations. Philippe Galle founded another long-lived family business. Theodor de Bry specialised in illustrating books on new colonial areas.[49]

17th century and the age of Rembrandt

editThe 17th century saw a continuing increase in the volume of commercial and reproductive printmaking; Rubens, like Titian before him, took great pains in adapting the trained engravers in his workshop to the particular style he wanted, though several found his demands too much and left.[50] The generation after him produced a number of widely dispersed printmakers with very individual and personal styles; by now etching had become the normal medium for such artists.

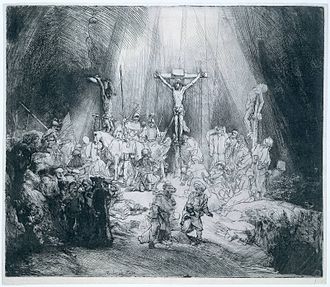

Rembrandt bought a printing-press for his house in the days of his early prosperity, and continued to produce etchings (always so called collectively, although Rembrandt mixed techniques by adding engraving and drypoint to some of his etchings) until his bankruptcy, when he lost both house and press. Fortunately his prints have always been keenly collected, and what seems to be a high proportion of his intermediate states have survived, often in only one or two impressions. He was clearly very directly involved in the printing process himself, and probably selectively wiped the plate of ink himself to produce effects surface tone on many impressions. He also experimented continually with the effects of different papers. He produced prints on a wider range of subjects than his paintings, with several pure landscapes, many self-portraits that are often more extravagantly fanciful than his painted ones, some erotic (at any rate obscene) subjects, and a great number of religious prints. He became increasingly interested in strong lighting effects, and very dark backgrounds. His reputation as the greatest etcher in the history of the medium was established in his lifetime, and never questioned since. Few of his paintings left Holland whilst he lived, but his prints were circulated throughout Europe, and his wider reputation was initially based on them alone.[51]

A number of other Dutch artists of the century produced original prints of quality, mostly sticking to the same categories of genre they painted. The eccentric Hercules Seghers and Jacob van Ruisdael produced landscapes in very small quantities, Nicolaes Berchem and Karel Dujardin Italianate landscapes with animals and figures, and Adriaen van Ostade peasant scenes. None was very prolific, but the Italianate landscape was the most popular type of subject; Berchem had a greater income from his prints than his paintings.[52]

Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione grew up in Genoa and was greatly influenced by the stays there of Rubens and van Dyck when he was a young artist. His etching technique was extremely fluent, and in all mediums he often repeats the same few subjects in a large number of totally different compositions. His early prints include a number of bravura treatments of classical and pastoral themes, whilst later religious subjects predominate. He also produced a large series of small heads of exotically dressed men, which were often used by other artists. He was technically innovative, inventing the monotype and also the oil sketch intended to be a final product. He, like Rembrandt, was interested in chiaroscuro effects (contrasts of light and dark), using a number of very different approaches.[53]

Jusepe de Ribera may have learned etching in Rome, but all his fewer than thirty prints were made in Naples during the 1620s when his career as a painter seems to have been in the doldrums. When the painting commissions began to flow again, he all but abandoned printmaking. His plates were sold after his death to a Rome publisher, who made a better job of marketing them than Ribera himself. His powerful and direct style developed almost immediately, and his subjects and style remain close to those of his paintings.[54]

Jacques Bellange was a court painter in Lorraine, a world that was to vanish abruptly in the Thirty Years War shortly after his death. No surviving painting of his can be identified with confidence, and most of those sometimes attributed to him are unimpressive. His prints, mostly religious, are Baroque extravaganzas that were regarded with horror by many 19th century critics, but have come strongly back into fashion—the very different Baroque style of another Lorraine artist Georges de La Tour has enjoyed a comparable revival. He was the first Lorraine printmaker (or artist) of stature, and must have influenced the younger Jacques Callot, who remained in Lorraine but was published in Paris, where he greatly influenced French printmaking.[55]

Callot's technical innovations in improving the recipes for etching ground were crucial in allowing etching to rival the detail of engraving, and in the long term spelt the end of artistic engraving. Previously the unreliable nature of the grounds used meant that artists could not risk investing too much effort in an etched plate, as the work might be ruined by leaks in the ground. Equally, multiple stoppings-out, enabling lines etched to different depths by varying lengths of exposure to the acid, had been too risky.[56] Callot led the way in exploiting the new possibilities; most of his etchings are small but full of tiny detail, and he developed a sense of recession in landscape backgrounds in etching with multiple bitings to etch the background more lightly than the foreground. He also used a special etching needle called an échoppe to produce swelling lines like those created by the burin in an engraving, and also reinforced the etched lines with a burin after biting; which soon became common practice among etchers. Callot etched a great variety of subjects in over 1400 prints, from grotesques to his tiny but extremely powerful series Les Grandes Misères de la guerre.[57] Abraham Bosse, a Parisian illustrative etcher popularized Callot's methods in a hugely successful manual for students. His own work is successful in his declared aim of making etchings look like engravings, and is highly evocative of French life at the middle of the century.

Wenzel Hollar was a Bohemian (Czech) artist who fled his country in the Thirty Years War, settling mostly in England (he was besieged at Basing House in the English Civil War, and then followed his Royalist patron into a new exile in Antwerp, where he worked with a number of the large publishers there). He produced great numbers of etchings in a straightforward realist style, many topographical, including large aerial views, portraits, and others showing costumes, occupations and pastimes.[58] Stefano della Bella was something of an Italian counterpart to Callot, producing many very detailed small etchings, but also larger and freer works, closer to the Italian drawing tradition.[59] Anthony van Dyck produced only a large series of portrait prints of contemporary notables, the Iconographia for which he only etched a few of the heads himself, but in a brilliant style, that had great influence on 19th century etching.[60] Ludwig von Siegen was a German soldier and courtier, who invented the technique of mezzotint, which in the hands of better artists than he was to become an important, mostly reproductive, technique in the 18th century.[61]

The last third of the century produced relatively little original printmaking of great interest, although illustrative printmaking reached a high level of quality. French portrait prints, most often copied from paintings, were the finest in Europe and often extremely brilliant, with the school including both etching and engraving, often in the same work. The most important artists were Claude Mellan, an etcher from the 1630s onwards, and his contemporary Jean Morin, whose combination of engraving and etching influenced many later artists. Robert Nanteuil was official portrait engraver to Louis XIV, and produced over two hundred brilliantly engraved portraits of the court and other notable French figures.[62]

Fine art printmaking after Rembrandt's death

editThe extremely popular engravings of William Hogarth in England were little concerned with technical printmaking effects; in many he was producing reproductive prints of his own paintings (a surprisingly rare thing to do) that only set out to convey his crowded moral compositions as clearly as possible. It would not be possible, without knowing, to distinguish these from his original prints, which have the same aim. He priced his prints to reach a middle and even upper working-class market, and was brilliantly successful in this.[63]

Canaletto was also a highly successful painter, and though his relatively few prints are vedute, they are rather different from his painted ones, and fully aware of the possibilities of the etching medium. Piranesi was primarily a printmaker, a technical innovator who extended the life of his plates beyond what was previously possible. His Views of Rome—well over a hundred huge plates—were backed by a serious understanding of Roman and modern architecture and brilliantly exploit the drama both of the ancient ruins and Baroque Rome. Many prints of Roman views had been produced before, but Piranesi's vision has become the benchmark. Gianbattista Tiepolo, near the end of his long career produced some brilliant etchings, subjectless capricci of a landscape of classical ruins and pine trees, populated by an elegant band of beautiful young men and women, philosophers in fancy dress, soldiers and satyrs. Bad-tempered owls look down on the scenes. His son Domenico produced many more etchings in a similar style, but of much more conventional subjects, often reproducing his father's paintings.[64]

The technical means at the disposal of reproductive printmakers continued to develop, and many superb and sought-after prints were produced by the English mezzotinters (many of them in fact Irish) and by French printmakers in a variety of techniques.[65] French attempts to produce high quality colour prints were successful by the last part of the century, although the techniques were expensive. Prints could now be produced that closely resembled drawings in crayon or watercolours. Some original prints were produced in these methods, but few major artists used them.[66]

The rise of the novel led to a demand for small, highly expressive, illustrations for them. Many fine French and other artists specialised in these, but clearly standing out from the pack is the work of Daniel Chodowiecki, a German of Polish origin who produced over a thousand small etchings. Mainly illustrations for books, these are wonderfully drawn, and follow the spirit of the times, through the cult of sentiment to the revolutionary and nationalist fervour of the start of the 19th century.[67]

Goya's superb but violent aquatints often look as though they are illustrating some unwritten work of fiction, but their meaning must be elucidated from their titles, often containing several meanings, and the brief comments recorded by him about many of them. His prints show from early on the macabre world that appears only in hints in the paintings until the last years. They were nearly all published in several series, of which the most famous are: Caprichos (1799), Los desastres de la guerra (The Disasters of War from after 1810, but unpublished for fifty years after). Rather too many further editions were published after his death, when his delicate aquatint tone had been worn down, or reworked.[68]

William Blake was as technically unconventional as he was in subject-matter and everything else, pioneering a relief etching process that was later to become the dominant technique of commercial illustration for a time. Many of his prints are pages for his books, with text and image on the same plate, as in the 15th century block-books.[69] The Romantic Movement saw a revival in original printmaking in several countries, with Germany taking a large part once again; many of the Nazarene movement were printmakers.[70] In England, John Sell Cotman etched many landscapes and buildings in an effective, straightforward style. J. M. W. Turner produced several print series including one, the Liber Studiorum, which consisted of seventy-one etchings with mezzotint that were influential on landscape artists; according to Linda Hults, this series of prints amounts to "Turner's manual of landscape types, and ... a statement of his philosophy of landscape."[71] With the relatively few etchings of Delacroix the period of the old master print can be said to come to an end.[72]

Printmaking was to revive powerfully later in the 19th and 20th centuries, in a great variety of techniques. In particular the Etching Revival, lasting from about the 1850s to the 1929 Wall Street crash rejuvenated the traditional monochrome techniques, even including woodcut, while lithography gradually became the most important printmaking technique over the same period, especially as it became more effective in using several colours in the same print.[73]

Inscriptions

editPrintmakers who signed their work often added inscriptions which characterised the nature of their contribution.

A list with their definitions includes:[74]

- Ad vivum indicates that a portrait was done "from life" and not after a painting, e.g., Aug. de St. Aubin al vivum delin. et sculp.

- Aq., aquaf., aquafortis denote the etcher

- D., del., delin., delineavit refer to the draughtsman

- Des., desig. refer to the designer

- Direx., Direxit. show direction or superintendence of pupil by master

- Ex., exc., excu., excud., excudit, excudebat indicate the publisher

- F., fe., ft, fec., fect, fecit, fa., fac., fact, faciebat indicate by whom the engraving was "made" or executed

- Formis, like excudit, describes the act of publication

- Imp. indicates the printer

- Inc., inci., incid., incidit, incidebat refer to him who "incised" or engraved the plate

- Inv., invenit, inventor mark the "inventor" or designer of the picture

- Lith. does not mean "lithographed by," but "printed by". Thus, Lith. de C. Motte, Lith. Lasteyrie, I. lith. de Delpech refer to lithographic printing establishments

- P., pictor, pingebat, pinx, pinxt, pinxit show who painted the picture from which the engraving was made

- S., sc., scul., sculpsit, sculpebat, sculptor appear after the engraver's name

Notes

edit- ^ Griffiths (1980), 16.

- ^ Field, Richard (1965). Fifteenth Century Woodcuts and Metalcuts. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art.

- ^ Hind (1935).

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 1–6, quotes 2, 33–42. Mayor, 5–10.

- ^ Mayor, 10.

- ^ Mayor, 14–17.

- ^ Mayor, 24–27.

- ^ A number have survived pasted on the inside of the lids of boxes or chests, like this example.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 34–42. Mayor, 32–60. Bartrum (1995), 17–19.

- ^ Bartrum, 17–63. Landau and Parshall, 167–174.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 46–51, 64.

- ^ Shestack (1967a), numbers 1–2. Mayor, 115–117.

- ^ Shestack (1967b). Shestack (1967a), numbers 4–19. Spangeberg, 1–3. Mayor, 118–123. Landau and Parshall, 46–50.

- ^ Shestack (1967a), numbers 34–115. Landau and Parshall, 50–56. Mayor, 130–135. Spangeberg, 5–7. Bartrum, 20–21.

- ^ Filedt Kok. Mayor, 124–129.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 56–63. Mayor, 138–140.

- ^ Levinson. Landau and Parshall, 65.

- ^ Langdale. Landau and Parshall, 65, 72–76.

- ^ Langdale.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 89. Levinson.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 71–72. Spangeberg, 4–5.

- ^ Levinson, no. 83.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 65–71. Mayor, 187–197. Spangeberg, 16–17.

- ^ Bartrum (2002). Bartrum (1995), 22–63. Landau and Parshall, see index. Mayor, 258–281.

- ^ Pon. Landau and Parshall, 347–358. Bartrum (1995), 9–11.

- ^ Pon. Landau and Parshall, see index.

- ^ Levinson, 289–334, 390–414. Landau and Parshall, 65–102 (see also index). Mayor, 143–156, 173, 223, 232.

- ^ Levinson, 440–455. Landau and Parshall, 199, 102.

- ^ Pon. Landau & Parshall, chapter IV, whose emphasis is disputed by Bury, 9–12.

- ^ Pon. Landau and Parshall, 117–146.

- ^ Jacobson, parts III and IV.

- ^ Landau and Parshall develop the traditional view of decline, which Bury contests in his Introduction, pp. 9–12, and seeks to demonstrate the opposite view throughout his work.

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 166–178.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 316–319, 332–333, 333 quoted.

- ^ Mayor, 228, 304–308, 567. Bartrum (1995), 11–12, 144, 158, 183–197. Landau and Parshall, 323–328 (Hopfers); 202–209, 337–346 (Altdorfer).

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 130–146. Landau and Parshall, see index, 179–202 on the chiaroscuro woodcut.

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 67–80.

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 212–221.

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 99–129. Mayor, 315–317. Landau and Parshall, 315–316.

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 221–237.

- ^ Bartrum (1995), 12–13.

- ^ Landau and Parshall, 146–161.

- ^ Bury. Reed and Walsh, 105–114 on Annibale and subsequent artists in etching. Mayor, 410, 516.

- ^ Jacobson, parts III and IV. Mayor, 354–357.

- ^ Marqusee. Jacobson, part II. Mayor, 358–359.

- ^ Mayor, 403–407, 410.

- ^ Mayor, 419–421. Spangeberg, 107–108.

- ^ Mayor, 422–426.

- ^ Mayor, 373–376, 408–410.

- ^ Mayor, 427–432.

- ^ White; Mayor, 472–505; Spangeberg, 164–168.

- ^ Mayor, 467–471. Spangeberg, 156–158 (Seghers), 170 (van Ostade), 177 (Berchem).

- ^ Reed and Wallace, 262–271. Mayor, 526–527.

- ^ Reed and Wallace, 279–285.

- ^ Griffiths and Hartley. Jacobson, part X. Mayor, 453–460.

- ^ Mayor, 455–460.

- ^ Hind (1923), 158–160.

- ^ Mayor, 344.

- ^ Reed and Wallace, 234–243. Mayor, 520–521, 538, 545.

- ^ Mayor, 433–435.

- ^ Griffiths (1980), 83–88. Mayor, 511–515.

- ^ Mayor, 289–290.

- ^ Mayor, 550–555.

- ^ Mayor, 576–584.

- ^ Griffiths (1996), 134–158 on English mezzotints and their collectors.

- ^ Spangeberg, 221–222. Mayor, 591–600.

- ^ Mayor, 568, 591–600.

- ^ Bareau. Mayor, 624–631.

- ^ Mayor, 608–611. Spangeberg, 262.

- ^ Griffiths and Carey.

- ^ Hults, 522.

- ^ Spangeberg, 260–261

- ^ Mayor, 660 onwards. Spangeberg, 263 onwards.

- ^ Weintenkampf, 278–279.

References

edit- Bareau, Juliet Wilson, Goya's Prints, The Tomás Harris Collection in the British Museum, 1981, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0-7141-0789-1

- Bartrum, Giulia (1995), German Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550. London: British Museum Press ISBN 0-7141-2604-7

- Bartrum, Giulia (2002), Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy. London: British Museum Press ISBN 0-7141-2633-0

- Bury, Michael; The Print in Italy, 1550–1620, 2001, British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-2629-2

- Filedt Kok, J.P. (ed.), Livelier than Life, The Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet, or the Housebook Master 1470–1500, Rijksmuseum/Garry Schwartz/Princeton University Press, 1985, ISBN 90-6179-060-3 / ISBN 0-691-04035-4

- Griffiths, Antony (1980), Prints and Printmaking; 2nd ed. of 1986 used, British Museum Press ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- Griffiths, Antony and Carey, Francis; German Printmaking in the Age of Goethe, 1994, British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-1659-9

- Griffiths, Antony & Hartley, Craig (1997), Jacques Bellange, c. 1575–1616, Printmaker of Lorraine. London: British Museum Press ISBN 0-7141-2611-X

- Griffiths, Antony, ed. (1996), Landmarks in Print Collecting: connoisseurs and donors at the British Museum since 1753. London: British Museum Press ISBN 0-7141-2609-8

- Hind, Arthur M. (1923), A History of Engraving and Etching. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co. (reprinted by Dover Publications, New York, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20954-7)

- Hind, Arthur M. (1935), An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co. (reprinted by Dover Publications, New York, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0)

- Hults, Linda, The Print in the Western World: An Introductory History, The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin, 1996,

- Karen Jacobson, ed (often wrongly cat. as Georg Baselitz), The French Renaissance in Prints, 1994, p. 470; Grunwald Center, UCLA, ISBN 0-9628162-2-1

- Landau, David & Parshall, Peter (1996), The Renaissance Print. New Haven: Yale U. P. ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Langdale, Shelley, Battle of the Nudes: Pollaiuolo's Renaissance Masterpiece, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 2002.

- Levinson, J. A., ed., Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art LCCN 73-79624

- Michael Marqusee, The Revelation of Saint John; Apocalypse Engravings by Jean Duvet, Paddington Press, London, 1976, ISBN 0-8467-0148-0

- Mayor, A. Hyatt, Prints and People, Princeton, NJ: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton U. P. ISBN 0-691-00326-2, Prints & people: a social history of printed pictures fully online from the MMA

- Pon, Lisa, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi, Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print, 2004, Yale UP, ISBN 978-0-300-09680-4

- Reed, Sue Welsh & Wallace, Richard, eds. (1989) Italian Etchers of the Renaissance and Baroque. Boston, Mass.: Museum of Fine Arts ISBN 0-87846-306-2

- Shestack, Alan (1967a) Fifteenth-century Engravings of Northern Europe. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art LCCN 67-29080 (Catalogue)

- Shestack, Alan (1967b), Master E.S.Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Spangeberg, K. L., ed., Six Centuries of Master Prints. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum ISBN 0-931537-15-0

- Weitenkampf, Frank (1921). How to Appreciate Prints, third revised edition (at Internet Archive). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- White, Christopher, The Late Etchings of Rembrandt. London: British Museum/Lund Humphries

External links

edit- The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; Timeline of Art

- Large list of links to museum etc. online images of old master prints Archived 2016-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Washington Post review of NGA exhibition on C15 German woodcuts

- Old master prints blog