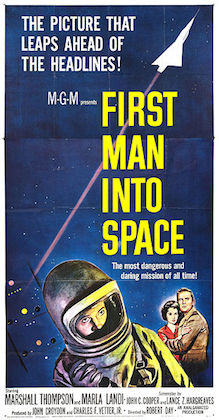

First Man into Space is a 1959 independently made British-American[1][2] black-and-white science fiction-horror film directed by Robert Day and starring Marshall Thompson, Marla Landi, Bill Edwards, and Robert Ayres. It was produced by John Croydon, Charles F. Vetter, and Richard Gordon for Amalgamated Films and was distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

| First Man into Space | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Robert Day |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Faithfull |

| Edited by | Peter Mayhew |

| Music by | Buxton Orr |

Production company | Amalgamated Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 78 min. |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $131,000 |

| Box office | $635,000 |

The film is based on a story by Wyott Ordung, while the plot was developed from a script that had been pitched to and rejected by AIP.[citation needed]

Plot

editThis section's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (November 2024) |

U. S. Navy Commander Charles "Chuck" Prescott is unsure if his brother, Lt. Dan Prescott, is the right choice for piloting the high altitude, rocket-powered Y-13. Air Force Space Command's Captain Ben Richards insists that Dan is their best pilot, even though when piloting the Y-12 in the ionosphere, he began experiencing difficulties. Dan ignored flight regulations upon landing by seeing his girlfriend rather than filing his flight report. Captain Richards, however, insists that Dan pilot the Y-13 after being checked out and briefed by Dr. Paul von Essen.

At 600,000 feet, Dan is supposed to level off the Y-13 and begin his descent, but he continues to climb, firing his emergency boost for more speed. He climbs to 1,320,000 feet (250 miles) and loses control while passing through a dense cloud of unknown material, forcing him to eject.

The New Mexico State Police report that a Mexican farmer spotted a parachute land south of Alvarado, New Mexico. Chief Wilson meets Commander Prescott near the wreckage; the automatic pilot escape mechanism and braking chute operated perfectly. An unknown rock-like material has encased the Y-13's fuselage; testing shows that it is completely impervious to X-rays, infrared, and ultraviolet light.

Later that night, a wheezing "creature" breaks into Alameda's New Mexico State Blood Bank, brutally murdering one of the blood bank's nurses; the thing then proceeds to drink vast quantities of blood. The next day, a newspaper headline reads "Terror Roams State" and tells of brutal and inhuman slaughtering of cattle on a farm next to the crash site. Both the dead cattle and the blood bank nurse show similar wounds. When Chuck and Chief Wilson examine the nurse's body, Chuck notices shiny specks around the wounds, as well as on the blood bank door. They see the same specks on the necks of the dead cattle; they also find a high-altitude oxygen lead from the Y-13.

Chuck suspects that the killings may have something to do with the crashed Y-13 and requests that Wilson send sample specks to Dr. von Essen at Aviation Medicine. The next day, test results show that they are particles of meteor dust and show no signs of structural damage from passage through the atmosphere. Later, Dr. von Essen explains the results to Chuck: Wherever the encrustation occurs on the Y-13 fuselage, the metal is intact. In places not encrusted, the metal has been transformed into a brittle, carbon-like substance, easily reduced to powder. Chuck theorizes that the covering may be some sort of "cosmic protection".

Three more killings are reported. Chuck assumes that the same covering that protected the Y-13 fuselage also coated "everything" inside the cockpit, which means that the creature behind the killings must be his brother Dan. Chuck theorizes that when the canopy burst, Dan's blood absorbed a high content of nitrogen as the protective coating quickly formed over his body, allowing him to survive. But with Dan's metabolism having been altered in space, his body and brain have now become starved of oxygen on Earth; he must now replace that oxygen by consuming any type of oxygen-enriched blood.

When Dan's coated helmet is found in a car with his latest victim, Chuck's theory is proven correct. Captain Richards and Chief Wilson put in a call to Washington. Suddenly, the hulking, wheezing, encrusted creature that was once Dan crashes through a nearby window in their building.

Chuck realizes that his brother is finding it difficult to breathe. Dan then has Dr. von Essen open the high-altitude testing chamber while he taps into the building's public address system, warning everyone to stay out of the corridors. Chuck instructs Dr. von Essen to relay directions over the system to Dan on how to find the high-altitude chamber. Dan follows the directions while Chuck follows behind.

Dan stumbles into the chamber. Chuck realizes that his brother's hands are too badly deformed for him to operate the controls, so Chuck enters the chamber to assist him. A technician quickly increases the chambers' altitude to 38,000 feet, enabling Dan to breathe more comfortably. While Chuck uses an oxygen mask, Dan's humanity is slowly restored. He has no recollection of events after he ejected from the Y-13, but, through labored breathing, says "I just had to be the first man into space". After which he collapses, breathing his last breath.

Cast

edit- Marshall Thompson as Commander Charles Ernest Prescott

- Marla Landi as Tia Francesca

- Bill Edwards as Lt. Dan Milton Prescott

- Robert Ayres as Captain Ben Richards

- Bill Nagy as Police Chief Wilson

- Carl Jaffe as Dr. Paul von Essen

- Roger Delgado as Mexican Consul Ramon de Guerrera

Production

editThe story idea for First Man into Space was conceived by Vetter, then the partner of producer Gordon. Several script elements for the film came from an original script written by Wyott Ordung titled Satellite of Blood. Ordung showed the script to AIP, who ultimately rejected it. However, Alex Gordon of AIP sent the script over to his brother, who liked its plot ideas; several elements from Ordung's script were then combined with Vetter's story. As a result, Ordung later acknowledged First Man into Space as his personal favourite of the films he had made.[3] Gordon successfully pitched the film idea to MGM. Gordon and Vetter then signed on as producers for the project because of the financial success of their two previous films, Fiend Without a Face (1958) and The Haunted Strangler (1958). Because of MGM's financial involvement, the £100,000 budget set for First Man into Space was slightly higher than for the producers' two previous films.[4][5]

Location filming for First Man into Space took place in the United States near a Brooklyn, New York air base but also in New Mexico. Most of the studio work was shot in a mansion near Hampstead Heath near London, because of the location's similarity to New York's Central Park; some exterior shots were done in Hampstead itself, while additional filming was done at other British locations.[5][6]

The aircraft seen in First Man into Space included stock footage of the takeoff and launch of the Bell X-1A from a Boeing B-29 Superfortress mother ship. A Redstone rocket launch was also featured.[7]

Edwards, who played pilot Dan Prescott and the space creature, needed his dialogue synched in post-production. The costume that he wore, a faux micro-meteor encrusted spacesuit, had small holes cut in its opaque head and face mask so the actor could see. Wearing the spacesuit proved difficult for Edwards, due to its tendency to heat up inside. It therefore could not be worn for extended periods. Breathing also became difficult due to the costume's poor air circulation. First Man into Space was directly influenced by The Quatermass Xperiment (1955).[8][5]

Release

editTheatrical release

editIt was a commercial success at the box office. According to MGM records, the film earned $310,000 in the United States and Canada and $325,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $95,000.[4]

Home media

editImage Entertainment released First Man into Space on DVD on 17 June 1998.[9] The Criterion Collection later re-released the film on DVD in 2007 as a part of its Monsters and Madmen box set, which included audio commentary on the making of the film with executive producer Gordon.[10]

Critical reception

editFirst Man into Space received mixed reviews upon its release.

Author and film critic Leonard Maltin awarded the film 2 out of 4 stars, stating that the film was better than its description sounds.[11]

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "Competently made, and with one eye on the American market, this highly coloured Science Fiction thriller presents its playboy-into-monster character sympathetically, while the make-up is uncommonly skilful and survives some strongly lit close-ups with no loss of conviction. The dialogue and an eerie climax are quite compelling, and although the film is still far from having achieved Ray Bradbury quality, it represents a move in the right direction."[12]

Variety wrote: "First Man Into Space is a good entry in the exploitation class. It has excitement and some genuine horror. It is generally well-made and suffers only from a tendency to get cosmic in philosophy as well as geography."[13]

Dennis Schwartz from Ozus' World Movie Reviews gave the film a C grade:

I've seen a lot of sci-fi films that didn't make as much sense as this one does. That doesn't mean that I think this B-film made too much sense. But it was bearable and it didn't try to sensationalize the monster's killing spree and if you are not too fussy about the banal dialogue and the phony Mexican accents, one might even find this film to be easy to take on a rainy Saturday afternoon.[14]

On his website Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings, Dave Sindelar gave the film a mixed review. He criticized the film's first half as being "a draggy bore" as well as the clichéd main characters, but commended Edward's and Delgado's performances and the film's strong second half.[15]

Allmovie gave the film a mixed review, calling the performances "uneven", but also noted that certain plot points were interesting enough to keep the viewer's interest throughout, with some of the suspense scenes being quite effective.[16]

Jamie S. Rich from Criterion Confessions.com gave the film a positive review, calling it "harmless fun" and complimenting the special effects simulating outer space.[17]

TV Guide awarded the film 2.5 out of 4 stars, describing it as "a scary and well done sci-fi exploitation film".[18]

See also

edit- The Quatermass Xperiment, a direct influence for the film

- The Incredible Melting Man, a 1977 horror film with the same premise

References

edit- ^ "First Man into Space". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "First Man into Space". American Film Institute Catalog. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Weaver and Askwith 2011, pp 68–79.

- ^ a b "The Eddie Mannix Ledger." Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study (Los Angeles).

- ^ a b c Weaver 2006. pp. 179–180.

- ^ "Filming Locations: 'First Man Into Space' (1959)." IMDb.com. Retrieved: 25 December 2015.

- ^ Santoir, Christian. "Review: 'First Man into Space'." Aeromovies. Retrieved: 17 February 2017.

- ^ Hamilton, 2013, pp. 39-–41.

- ^ "Releases: 'The First Man into Space '(1959)." AllMovie. Retrieved: 25 December 2015.

- ^ "Monsters and Madmen – The Criterion Collection." Criterion.com. Retrieved: 25 December 2015.

- ^ Leonard Maltin; Spencer Green; Rob Edelman (January 2010). Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide. Plume. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-452-29577-3.

- ^ "First Man into Space". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 26 (300): 45. 1 January 1959. ProQuest 1305820809 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "First Man into Space". Variety. 213 (12): 6. 18 February 1959 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Schwartz, Dennis. "firstmanintospace". Sover.net. Dennis Schwartz. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Sindelar, Dave (20 February 2016). "First Man Into Space (1959)". Fantastic Movie Musings.com. Dave Sindelar. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Review" 'The First Man into Space' (1959). AllMovie, 12 November 2014. Retrieved: 25 December 2015.

- ^ Rich, Jamie. "Criterion Confessions: MONSTERS & MADMEN (#364): FIRST MAN INTO SPACE – #365". Criterion Confessions.com. Jamie S. Rich. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Review: 'First Man Into Space'." TV Guide.com, 12 November 2014. Retrieved: 25 December 2015.

Bibliography

edit- Hamilton, John. The British Independent Horror Film, 1951–70. Hailsham, UK: Hemlock Books, 2013. ISBN 978-1-903254-33-2.

- Maltin, Leonard, Spencer Green and Rob Edelman. Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide. New York, Plume, 2010. ISBN 978-0-452-29577-3.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies, American Science Fiction Movies of the '50s, Vol II: 1958–1962. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1986. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Weaver, Tom. Interviews with B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers: Writers, Producers, Directors, Actors, Moguls and Makeup. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2006. ISBN 978-0-7864-2858-8.

- Weaver, Tom and Robin Askwith. The Horror Hits of Richard Gordon. Albany, Georgia: Bear Manor Media, 2011. ISBN 978-1-5939-3641-9.

External links

edit- First Man into Space at IMDb

- First Man into Space at AllMovie

- First Man into Space at Rotten Tomatoes

- First Man into Space at the TCM Movie Database

- First Man Into Space, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Began to Seriously Consider Marrying a Monster from Outer Space an essay by Michael Lennick at the Criterion Collection

- Song "inspired by the MGM production" at Discogs (list of releases)