The Wars of Castro were a series of conflicts during the mid-17th century revolving around the ancient city of Castro (located in present-day Lazio, Italy), which eventually resulted in the city's destruction on 2 September 1649. The conflict was a result of a power struggle between the papacy – represented by members of two deeply entrenched Roman families and their popes, the Barberini and Pope Urban VIII and the Pamphili and Pope Innocent X – and the Farnese dukes of Parma, who controlled Castro and its surrounding territories as the Duchy of Castro.

| Wars of Castro | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

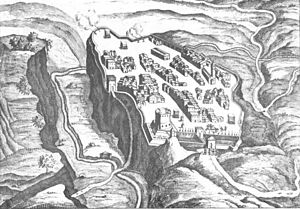

The city of Castro, on which the Wars of Castro centered. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Precursors

editPapal politics of the mid-17th century were complicated, with frequently shifting military and political alliances across the Catholic world. While it is difficult to trace the precise origins of the feud between the duchy of Parma and the papacy, its origins can be looked for in political maneuverings occurring in the years or even decades preceding the start of military action.

In 1611 a group of conspirators, nobles from Modena and Mantua, was accused of devising a plot to assassinate Ranuccio I Farnese, Duke of Parma and other members of the Farnese family in Parma. In reality, the plot had been "uncovered" when a prisoner (being held for unrelated crimes) confessed to it and implicated members of various noble houses. Though the accusations were likely untrue, 100 of the "conspirators" were tortured and eventually executed in Parma's main square in 1612. Many of their estates were confiscated leaving a large number of now legitimately discontented nobles. Until his death in 1622, Ranuccio remained paranoid about future assassination attempts and about curses from witches and heretics. He persecuted "witches" and alleged conspirators savagely and even had his own mistress, Claudia Colla, burned to death. He remained convinced that other noble families were plotting his downfall.[1]

However, tensions between the Farnese and other Italian nobility were not limited to local events in Parma. Historian Leopold von Ranke gives an account of a 1639 visit to Rome by Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza. The Duke arrived in Rome to great fanfare – he was given gifts and escorted around the city by Pope Urban's Cardinal-nephews, Antonio Barberini and Francesco Barberini. But the Duke refused to pay due deference to the Pope's other nephew; the newly appointed Prefect of Rome, Taddeo Barberini. As the Duke prepared to leave, he suggested that an escort from the city (ordinarily reserved for the Grand Duke of Tuscany) would be appropriate. Francesco Barberini refused. The Duke took his leave but urged the Pope to chastise both Cardinal-nephews.[2]

The nephews were furious and convinced the pope to punish the Duke by banning grain shipments originating in Castro from being distributed in Rome and the surrounding territory, thereby depriving the Duke of an important source of income.[3] Duke Odoardo's Roman creditors saw their chance – the Duke was unable to pay his debts, which he had accumulated in military adventures against the Spanish in Milan and in luxurious living. The unpaid and unhappy creditors sought relief from the pope, who turned to military action in an attempt to force payment.[2]

Preparations for war

editPope Urban VIII responded to the requests of Duke Odoardo's creditors by sending his nephew Antonio, Fabrizio Savelli and Marquis Luigi Mattei to occupy the city of Castro. Papal forces also included commanders Achille d'Étampes de Valençay and Marquis Cornelio Malvasia.

At the same time, the pope sent cardinal Bernardino Spada as plenipotentiary in an effort to resolve the crisis. Spada successfully negotiated a truce but when the pope's military leaders became aware that the dukes were massing troops to counter their own (in case discussions with Spada came to naught), Urban VIII declared the articles of peace null and void and claimed Spada had negotiated them without his consent.[4] Spada later published a manifesto detailing his version of events which, according to contemporary John Bargrave, many accepted to be the truth.

Urban VIII had been amassing troops in Rome throughout 1641. Mercenaries and regular troops filled the streets and Antonio Barberini was forced to institute special measures to maintain authority over the city. But the papacy needed yet more troops. The Duke of Ceri, who had been imprisoned for wounding a papal officer in a dispute over the management of the Duchy of Ceri, and Mario Frangipani, imprisoned for murdering someone on his estate, were both pardoned by the pope and given command of papal troops.[5]

First War of Castro

editOn 12 October, Luigi Mattei led 12,000 infantry and up to 4,000 cavalry against the fortified town.[6] The pope's forces were met by a contingent of 40 troops guarding a bridge leading to the town; a short burst of cannon-fire resulting in a single death was enough to prompt capitulation.[2] Castro, and several other small towns nearby, surrendered. Fabrizio Savelli, though, proved to be an unenthusiastic commander. The army was split into three and the Pope's nephew, Taddeo Barberini, replaced Savelli as Generalissimo, arriving with one contingent in the papal city of Ferrara on 5 January 1642. On 11 January the opera L'Armida, by Barberini house composer Marco Marazzoli, was presented in his honour and Marazzoli composed a work Le pretensioni del Tebro e del Po to commemorate recent events.

On 13 January, Urban excommunicated Odoardo and rescinded his fiefdoms (which had been granted by Pope Paul III – Odoardo's great-great-great-grandfather – in 1545). Odoardo countered with a military march of his own, this time on the papal state itself and his forces were soon close enough to threaten Rome. But Odoardo faltered and the Pope was able to fortify Rome and raise a new army - this time 30,000 troops; enough to drive the Duke back to his own territory. Odoardo forged alliances with Venice, Modena, and Tuscany which was under the command of his brother-in-law, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany.[2]

At first, Pope Urban threatened to excommunicate anyone who helped Odoardo, but Odoardo's allies insisted their conflict was not with the papacy, but rather with the Barberini family (of which the Pope happened to be a member). When this failed, the Pope attempted to call on old alliances of his own and turned to Spain for assistance. But he received little help as Spanish forces were fully occupied by the Thirty Years' War. As it was, most of the troops fighting on the side of the papacy were French, most of those fighting for the Dukes were German.[2]

Exasperated, the Pope increased taxes and raised additional forces and the war continued with Cardinal Antonio Barberini (Taddeo's brother) finding success against the Venetians and Modenese. But Papal forces suffered significant defeats in the area around Lake Trasimeno at the hands of the Tuscans (the Battle of Mongiovino). Fighting in the style typical of 17th-century Europe, by the latter half of 1643 neither side had made significant ground, though both sides had spent significant amounts of money perpetuating the conflict. It has been suggested that Pope Urban and forces loyal to the Barberini spent some 6 million thalers[7] during the 4 years of the conflict that fell within Pope Urban's reign.

The papal forces suffered a crucial defeat at the Battle of Lagoscuro on 17 March 1644 and were forced to surrender. Antonio Barberini was almost captured; saved, "only by the fleetness of his horse".[2] Peace was agreed to in Ferrara on 31 March.

Under the terms of the peace, Odoardo was readmitted to the Catholic Church and his fiefdoms were restored to him. Grain shipments from Castro to Rome were once again allowed and Odoardo was to resume payments to his Roman creditors. This peace settlement concluded the First War of Castro and was widely considered a disgrace to the papacy, which was unable to impose its will through use of military force. Urban is said to have been so distressed that after signing the peace agreements he was overcome by a severe malady which stayed with him until his death.

Urban's death and Barberini exile

editPope Urban VIII died just a few months after the peace settlement was agreed to, on 29 July and on 15 September Pamphili family Pope Innocent X was elected to replace him. Almost immediately, Innocent X began an investigation into the financing of the conflict. In total, the first war is estimated to have cost the papacy 12 million scudi and special taxes were levied against the residents of Rome to refill church coffers.[2] The nephews of Pope Urban VIII who had led the papal armies, brothers Antonio Barberini (Antonio the Younger), Taddeo Barberini and Francesco Barberini, were forced to abandon Rome and flee to France, assisted by Cardinal Mazarin.[8] There they depended on the hospitality of Louis XIV, King of France.

Taddeo Barberini died in Paris in 1647 but in 1653 Antonio and Francesco Barberini were allowed to return to Rome after sealing a reconciliation with Innocent X through the marriage of Taddeo's son Maffeo Barberini and Olimpia Giustiniani (a niece of Innocent X). Relations were also later repaired with some of Odoardo's former allies when Taddeo's daughter, Lucrezia Barberini married Francesco I d'Este, Duke of Modena who had led Modenese forces against the Barberini.

Second War of Castro

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

With peace agreed to and with Barberini power-brokers dead or exiled, the citizens of Castro were left alone. But Odoardo Farnese, who had signed the original peace accord, died in 1646 and was succeeded by his son Ranuccio II Farnese, Duke of Parma.

In 1649, Ranuccio refused to pay Roman creditors as his father had agreed in the treaty signed five years prior. He also refused to recognize the new bishop of Castro, Monsignor Cristoforo Giarda, appointed by Pope Innocent X. When the bishop was killed en route to Castro, near Monterosi, Pope Innocent X accused Duke Ranuccio and his supporters of murdering him.

In retaliation for this alleged crime, forces loyal to the Pope marched on Castro. Ranuccio attempted to ride out against the Pope's forces but was routed by Luigi Mattei.[9] On 2 September, on the Pope's orders, the city was completely destroyed. Not only did Pope Innocent's troops destroy the fortifications and general buildings of Castro, they destroyed the churches as well so as to completely sever all links between the city and the papacy.[10] As a final insult, the troops destroyed Duke Ranuccio's family Palazzo Farnese and erected a column reading Qui fu Castro ("Here stood Castro").

Duke Ranuccio II was forced to cede control of the territories around Castro to the pope, who then attempted to use the land to settle debts with Ranuccio's creditors. This marked the end of the Second War of Castro and the end of Castro itself – the city was never rebuilt.

Notes

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Later replaced by Taddeo Barberini.

- ^ As commander of papal loyalists and hired mercenaries.

- ^ As commander of cavalry.

- ^ As commander of cavalry.

- ^ As commander of the forces of the Republic of Venice, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchy of Modena and Reggio.

- ^ As commander of mercenary Modenese forces loyal to Francesco I d'Este.

Citations

edit- ^ Farnese: Pomp, Power and Politics in Renaissance Italy by Helge Gamrath (2007)

- ^ a b c d e f g History of the popes; their church and state (Volume III) by Leopold von Ranke (Wellesley College Library, 2009)

- ^ War over Parma by Alexander Ganse (KLMA, 2004)

- ^ Pope Alexander the Seventh and the College of Cardinals by John Bargrave, edited by James Craigie Robertson (reprint; 2009)

- ^ Power And Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies by P.J.A.N. Rietbergen (Brill, 2006)

- ^ The Castro Wars Archived 3 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Paul Armas Lepisto (Olive University)

- ^ The Thirty Years' War by Geoffrey Parker (Routledge, 1997)

- ^ The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church by S. Miranda (Florida International University, 2003)

- ^ Cours d'histoire des états européens depuis le bouleversement de l'Empire by Maximilian Samson Friedrich Schoell. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved on 2 September 2011.

- ^ Venice, Austria and the Turks in the seventeenth century by Kenneth Meyer Setton (American Philosophical Society, 1991)

Bibliography

edit- Villari, Luigi (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–184.