Flemish people or Flemings (Dutch: Vlamingen [ˈvlaːmɪŋə(n)] ) are a Germanic ethnic group native to Flanders, Belgium, who speak Flemish Dutch. Flemish people make up the majority of Belgians, at about 60%.

Vlamingen (Dutch) | |

|---|---|

Flag of Flanders, the symbol of the Flemish people. | |

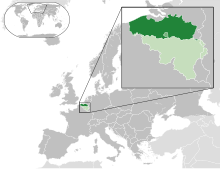

Flemish Community in Belgium and Europe | |

| Total population | |

| c. 7 million (2011 estimate) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 6,450,765[1] | |

| Indeterminable[a] (352,630 Belgians)[2] | |

| 187,750[3] | |

| 13,840–176,615[b][4] | |

| 55,200[3] | |

| 15,130[3] | |

| 6,000[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Dutch (Belgian Dutch, West Flemish, Limburgish) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly and historically Roman Catholic with Protestant minority[a] Increasingly irreligious | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dutch, Walloons, Afrikaners, Vilamovians | |

^a U.S. population census does not differentiate between Walloons and Flemish, therefore the number of the latter is unknown. ^b In 2011, 13,840 respondents stated Flemish ethnic origin. Another 176,615 reported Belgian. See List of Canadians by ethnicity | |

| Person | Fleming (Vlaming) |

|---|---|

| People | Flemings (Vlamingen) |

| Language | Flemish (Vlaams), VGT (Vlaamse Gebarentaal) |

| Country | Flanders (Vlaanderen) |

Flemish was historically a geographical term, as all inhabitants of the medieval County of Flanders in modern-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands were referred to as "Flemings" irrespective of their ethnicity or language.[5] The contemporary region of Flanders comprises a part of this historical county, as well as parts of the medieval duchy of Brabant and the medieval county of Loon, where the modern national identity and culture gradually formed.

History

editThe sense of "Flemish" identity increased significantly after the Belgian Revolution. Prior to this, the term "Vlamingen" in the Dutch language was in first place used for the inhabitants of the former County of Flanders.[citation needed] Flemish, however, had been used since the 14th century to refer to the language and dialects of both the peoples of Flanders and the Duchy of Brabant.[6] [7]

In 1830, the southern provinces of the United Netherlands proclaimed their independence. French-dialect speaking population, as well as the administration and elites, feared the loss of their status and autonomy under Dutch rule while the rapid industrialization in the south highlighted economic differences between the two. Under French rule (1794–1815), French was enforced as the only official language in public life, resulting in a Francization of the elites and, to a lesser extent, the middle classes. The Dutch king allowed the use of both Dutch and French dialects as administrative languages in the Flemish provinces. He also enacted laws to reestablish Dutch in schools.[8] The language policy was not the only cause of the secession; the Roman Catholic majority viewed the sovereign, the Protestant William I, with suspicion and were heavily stirred by the Roman Catholic Church which suspected William of wanting to enforce Protestantism. Lastly, Belgian liberals were dissatisfied with William for his allegedly despotic behaviour.[citation needed]

Following the revolt, the language reforms of 1823 were the first Dutch laws to be abolished and the subsequent years would see a number of laws restricting the use of the Dutch language.[9] This policy led to the gradual emergence of the Flemish Movement, that was built on earlier anti-French feelings of injustice, as expressed in writings (for example by the late 18th-century writer, Jan Verlooy) which criticized the Southern Francophile elites. The efforts of this movement during the following 150 years, have to no small extent facilitated the creation of the de jure social, political and linguistic equality of Dutch from the end of the 19th century.[citation needed]

After the Hundred Years War many Flemings migrated to the Azores. By 1490 there were 2,000 Flemings living in the Azores. Willem van der Haegen was the original sea captain who brought settlers from Flanders to the Azores. Today many Azoreans trace their genealogy from present day Flanders. Many of their customs and traditions are distinctively Flemish in nature such as windmills used for grain, São Jorge cheese and several religious events such as the imperios and the feast of the Cult of the Holy Spirit.

Identity and culture

editWithin Belgium, Flemings form a clearly distinguishable group set apart by their language and customs. Various cultural and linguistic customs are similar to those of the Southern part of the Netherlands.[10] Generally, Flemings do not identify themselves as being Dutch and vice versa.[11]

There are popular stereotypes in the Netherlands as well as Flanders which are mostly based on the 'cultural extremes' of both Northern and Southern culture.[12] Alongside this overarching political and social affiliation, there also exists a strong tendency towards regionalism, in which individuals greatly identify themselves culturally through their native province, city, region or dialect they speak.

Language

editFlemings speak Dutch (specifically its southern variant, which is often colloquially called 'Flemish'). It is the majority language in Belgium, being spoken natively by three-fifths of the population. Its various dialects contain a number of lexical and a few grammatical features which distinguish them from the standard language.[13] As in the Netherlands, the pronunciation of Standard Dutch is affected by the native dialect of the speaker. At the same time East Flemish forms a continuum with both Brabantic and West Flemish. Standard Dutch is primarily based on the Hollandic dialect (spoken in the northwestern Netherlands) and to a lesser extent on Brabantic, which is the most dominant Dutch dialect of the Southern Netherlands and Flanders.

Religion

editApproximately 75% of the Flemish people are by baptism assumed Roman Catholic, though a still diminishing minority of less than 8% attends Mass on a regular basis and nearly half of the inhabitants of Flanders are agnostic or atheist. A 2006 inquiry in Flanders showed 55% chose to call themselves religious and 36% believe that God created the universe.[14]

National symbols

editThe official flag and coat of arms of the Flemish Community represents a black lion with red claws and tongue on a yellow field (or a lion rampant sable armed and langued gules).[15] A flag with a completely black lion had been in wide use before 1991 when the current version was officially adopted by the Flemish Community. That older flag was at times recognized by government sources (alongside the version with red claws and tongue).[16][17] Today, only the flag bearing a lion with red claws and tongue is recognized by Belgian law, while the flag with the all-black lion is mostly used by Flemish separatist movements. The Flemish authorities also use two logos of a highly stylized black lion which show the claws and tongue in either red or black.[18] The first documented use[19] of the Flemish lion was on the seal of Philip d'Alsace, count of Flanders of 1162. As of that date the use of the Flemish coat of arms (or a lion rampant sable) remained in use throughout the reigns of the d'Alsace, Flanders (2nd) and Dampierre dynasties of counts. The motto "Vlaanderen de Leeuw" (Flanders the lion) was allegedly present on the arms of Pieter de Coninck at the Battle of the Golden Spurs on July 11, 1302.[20][21][22] After the acquisition of Flanders by the Burgundian dukes the lion was only used in escutcheons. It was only after the creation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands that the coat of arms (surmounted by a chief bearing the Royal Arms of the Netherlands) once again became the official symbol of the new province East Flanders.

Diaspora

editBrazil

editCanada

editThe first sizeable wave of Flemish migration to Canada occurred in the 1870s, when Saint Boniface proved a popular destination for work in local flour mills, brick yards and railway yards. Similarly, Flemish were drawn to smaller villages in Manitoba, where jobs in farming were available.[23] In the early 20th century, Flemish settled in significant numbers across Ontario, particularly attracted by the tobacco-growing industry, in the towns of Chatham, Leamington, Tillsonburg, Wallaceburg, Simcoe, Sarnia and Port Hope.[24][25]

France and the Netherlands

editThe original County of Flanders encompassed areas which today belong to France and the Netherlands, but are still host to people of Flemish descent and some continued use of Flemish Dutch. Namely, these are Zeelandic Flanders and the Arrondissement of Dunkirk (historically known as French Westhoek). The people of North Brabant also share related ancestry.

Poland

editThere were migrations of Flemish people to medieval and early modern Poland. The Flemming noble family of Flemish origin first settled in Pomerania and modern Poland in the 13th century with the village of Buk becoming the first estate of the family in the region.[26] The family reached high-ranking political and military posts in Poland in the 18th century, and Polish Princess Izabela Czartoryska and statesman Adam Jerzy Czartoryski were their descendants. There are several preserved historical residences of the family in Poland.

Flemish architects Anthonis van Obbergen and Willem van den Blocke migrated to Poland, where they designed a number of mannerist structures, and Willem van den Blocke also has sculpted multiple lavishly decorated epitaphs and tombs in Poland.[27]

Portugal

editFlemish people also emigrated at the end of the fifteenth century, when Flemish traders conducted intensive trade with Spain and Portugal, and from there moved to colonies in America and Africa.[28] The newly discovered Azores were populated by 2,000 Flemish people from 1460 onwards, making these volcanic islands known as the "Flemish Islands".[29][30][31] For instance, the city of Horta derives its name from Flemish explorer Josse van Huerter.[32]

South Africa

editUnited Kingdom

editPrior to the 1600s, there were several substantial waves of Flemish migration to the United Kingdom. The first wave fled to England in the early 12th century, escaping damages from a storm across the coast of Flanders, where they were largely resettled in Pembrokeshire by Henry I. They changed the culture and accent in south Pembrokeshire to such an extent, that it led to the area receiving the name Little England beyond Wales. Haverfordwest[33] and Tenby consequently grew as important settlements for the Flemish settlers.[34]

In the 14th century, encouraged by King Edward III and perhaps in part due to his marriage to Philippa of Hainault, another wave of migration to England occurred when skilled cloth weavers from Flanders were granted permission to settle there and contribute to the then booming cloth and woollen industries.[35] These migrants particularly settled in the growing Lancashire and Yorkshire textile towns of Manchester,[36] Bolton,[37] Blackburn,[38] Liversedge,[39] Bury,[40] Halifax[41][42] and Wakefield.[43]

Demand for Flemish weavers in England occurred again in both the 15th and 16th centuries, but this time particularly focused on towns close to the coastline of East Anglia and South East England. Many from this generation of weavers went to Colchester, Sandwich[44] and Braintree.[45] In 1582, it was estimated that there could have been around 1,600 Flemish in Sandwich, today almost half of its total population.[46] London, Norwich and North Walsham, however, were the most popular destinations, and the nickname for Norwich City F.C. fans, Canaries, is derived from the fact that many of the Norfolk weavers kept pet canaries.[47][48] The town of Whitefield, near Bury, also claims to owe its name to Flemish cloth weavers that settled in the area during this era, who would lay their cloths out in the sun to bleach them.[49]

These waves of settlement are also evidenced by the common surnames Fleming, Flemings, Flemming and Flemmings.

United States

editIn the United States, the cities of De Pere and Green Bay in Wisconsin attracted many Flemish and Walloon immigrants during the 19th century.[50][51] The small town of Belgique was settled almost entirely by Flemish immigrants, although a significant number of its residents left after the Great Flood of 1993.

See also

editNotes and references

edit- ^ Mainly in the Reformed tradition, although also a scarce population of Lutherans.

- ^ "Structuur van de bevolking – België / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest / Vlaams Gewest / Waals Gewest / De 25 bevolkingsrijke gemeenten (2000–2006)" [Structure of the population - Belgium / Brussels-Capital Region / Flemish Region / Walloon Region / The 25 populated municipalities (2000-2006)] (in Dutch). Belgian Federal Government Service (ministry) of Economy – Directorate-general Statistics Belgium. 2007. Retrieved May 23, 2007.— Note: 59% of the Belgians can be considered Flemish, i.e., Dutch-speaking: Native speakers of Dutch living in Wallonia and of French in Flanders are relatively small minorities which furthermore largely balance one another, hence counting all inhabitants of each unilingual area to the area's language can cause only insignificant inaccuracies (99% can speak the language). Dutch: Flanders' 6.079 million inhabitants and about 15% of Brussels' 1.019 million are 6.23 million or 59.3% of the 10.511 million inhabitants of Belgium (2006); German: 70,400 in the German-speaking Community (which has language facilities for its less than 5% French-speakers), and an estimated 20,000–25,000 speakers of German in the Walloon Region outside the geographical boundaries of their official Community, or 0.9%; French: in the latter area as well as mainly in the rest of Wallonia (3.414 - 0.093 = 3.321 million) and 85% of the Brussels inhabitants (0.866 million) thus 4.187 million or 39.8%; together indeed 100%[dead link]

- ^ Results Archived 2020-02-12 at archive.today American Fact Finder (US Census Bureau)

- ^ a b c d "Vlamingen in de Wereld". Vlamingen in de Wereld, a foundation offering services for Flemish expatriates, with cooperation of the Flemish government. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ 2011 Canadian Census

- ^ Lebon (1838). La Flandre Wallonne aux 16e et 17e siшcle suivie... de notes historiques ... - Lebon - Google Livres. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ^ Lode Wils. De lange weg van de naties in de Lage Landen, p.46. ISBN 90-5350-144-4

- ^ Wright, Sue; Kelly-Holmes, Helen (1995). Languages in contact and conflict ... - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-85359-278-2. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ E.H. Kossmann, De lage landen 1780/1980. Deel 1 1780-1914, 1986, Amsterdam, p. 128

- ^ Jacques Logie, De la régionalisation à l'indépendance, 1830, Duculot, 1980, Paris-Gembloux, p. 21

- ^ National minorities in Europe, W. Braumüller, 2003, page 20.

- ^ Nederlandse en Vlaamse identiteit, Civis Mundi 2006 by S.W Couwenberg. ISBN 90-5573-688-0. Page 62. Quote: "Er valt heel wat te lachen om de wederwaardigheden van Vlamingen in Nederland en Nederlanders in Vlaanderen. Ze relativeren de verschillen en beklemtonen ze tegelijkertijd. Die verschillen zijn er onmiskenbaar: in taal, klank, kleur, stijl, gedrag, in politiek, maatschappelijke organisatie, maar het zijn stuk voor stuk varianten binnen één taal-en cultuurgemeenschap." The opposite opinion is stated by L. Beheydt (2002): "Al bij al lijkt een grondiger analyse van de taalsituatie en de taalattitude in Nederland en Vlaanderen weinig aanwijzingen te bieden voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit. Dat er ook op andere gebieden weinig aanleiding is voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit is al door Geert Hofstede geconstateerd in zijn vermaarde boek Allemaal andersdenkenden (1991)." L. Beheydt, "Delen Vlaanderen en Nederland een culturele identiteit?", in P. Gillaerts, H. van Belle, L. Ravier (eds.), Vlaamse identiteit: mythe én werkelijkheid (Leuven 2002), 22-40, esp. 38. (in Dutch)

- ^ Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: Accounting for the past, 1650-2000; by D. Fokkema, 2004, Assen.

- ^ G. Janssens and A. Marynissen, Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (Leuven/Voorburg 2005), 155 ff.

- ^ Inquiry by 'Vepec', 'Vereniging voor Promotie en Communicatie' (Organisation for Promotion and Communication), published in Knack magazine 22 November 2006 p.14 [The Dutch language term 'gelovig' is in the text translated as 'religious'; more precisely it is a very common word for believing in particular in any kind of God in a monotheistic sense, and/or in some afterlife.

- ^ (in Dutch) Flemish Authorities - coat of arms Archived 2003-12-04 at the Wayback Machine De officiële voorstelling van het wapen van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, in zwart - wit en in kleur, werd vastgesteld bij de ministeriële besluiten van 2 januari 1991 (BS 2 maart 1991), en zoals afgebeeld op de bijlagen bij deze besluiten. - flag Archived 2007-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Samples of the black lion without red tongue and claws for the province of East and West Flanders before the regionalization of Belgian provinces:Prof. Dr. J. Verschueren; Dr. W. Pée & Dr. A. Seeldraeyers (1 December 1997). Verschuerens Modern Woordenboek (6th revised ed.). N.V. Brepols, Turnhout. volume M–Z, plate "Wapenschilden" left of p. 1997. This dictionary/encyclopaedia was put on the list of school books allowed to be used in the official secondary institutions of education on March 8, 1933 by the Belgian government.

- ^ Armorial des provinces et des communes de Belgique, Max Servais: pages 217-219, explaining the 1816 origin of the Flags of the provinces of East and West Flanders and their post 1830 modifications

- ^ Flemish authorities show a logo of a highly stylized black lion either with red claws and tongue (sample: 'error' page by ministry of the Flemish Community) Archived 2005-04-06 at the Wayback Machine or a completely black version.

- ^ Armorial des provinces et des communes de Belgique, Max Servais

- ^ "Flanders (Belgium)". Flags of the World web site. 2006-12-02. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Velde, François R. (2000-04-01). "War-Cries". Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Olivier, M. (1995-06-13). "Voorstel van decreet houdende instelling van de Orde van de Vlaamse Leeuw (Vlaamse Raad, stuk 36, buitengewone zitting 1995 – Nr. 1)" (PDF) (in Dutch). Flemish Parliament. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ [1] The Belgians In Canada, Cornelius J. Jaenen, 1991.

- ^ "This migration resulted in a Flemish corridor stretching from Wallaceburg, through Chatham, up to Leamington."/"Flemish moved to a region stretching from Aylmer to Simcoe." The Netherlandic Presence in Ontario, Frans J. Schryer, 1998.

- ^ "The most important Flemish settlement was located at the heart of the tobacco-growing region, within the London-Kitchener-Dunnville triangle."/"In the mid-1920s, another important settlement developed around Sarnia on Lake Huron." The Flemish and Dutch Migrant Press in Canada: A Historical Investigation, Jennifer Vrielinck. Accessed August 3, 2019.

- ^ Baltische Studien. Vol. 1. 1832. p. 105.

- ^ "Willem van den Blocke". Culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Flemish merchants" (PDF).

- ^ "De vergeten Vlamingen van de Azoren – Lusophonia" (in Dutch). 2007-04-02. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ "De Azoren, de Vlaamse eilanden". Het Nieuwsblad (in Flemish). 2011-03-05. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ "Meer Geschiedenis van de Azoren". www.azoresweb.com. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ "História – Freguesia das Angústias" (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ "It (Haverfordwest) was probably the main area of Flemish settlement in Pembrokeshire." Archived 2019-08-01 at the Wayback Machine Haverfordwest Town Council. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ The Flemish colonists in Wales BBC. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ Fourteenth Century England - A Place Flemish Rebels Called 'Home' England's Immigrant's 1330-1550. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester. AD 1363 The Victorian Web. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "Remember our Flemish 'immigrant' ancestors who came to Bolton and established the spinning and weaving industry on which the town was subsequently built." The Bolton News. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "Flemish weavers who settled in the area in the 14th Century helped to develop the woollen cottage industry." Community Rail Lancashire. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "Settlement of Flemish Cloth Workers in Hartshead and Liversedge" Spen Valley, Past and Present by Frank Peel, 1893.

- ^ "In the mid 1300's, it is said that Flemish weavers settled in Bury, giving rise to the woollen industry in the town, and the reason for a sheep being depicted on the Coat of Arms." Lancashire Online Parish Clerks. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "A considerable number of Flemish weavers settled in Halifax in the West Riding at the close of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the fifteenth century." Weaving in Yorkshire. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "The cloth trade enjoyed a fillip when a considerable number of Flemish weavers settled in Halifax in the West Riding at the close of the fourteenth century." History of the Wool Industry in England, the Yorkshire West Riding and Pudsey & Halifax. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "About 1340, Flemish weavers settled in this town" Some Field Family Journeys: Selected Descendants of Roger Del Feld by Warren James Field, 2011.

- ^ Flemish Immigrants In South-East England During The Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "The weaving skills of Flemish immigrants brought a further boost to Braintree's prosperity in the 16th century" Archived 2019-08-01 at the Wayback Machine A Brief History of Braintree. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "From the early 1580s, the numbers of immigrants began to decline as many of the strangers returned to the Netherlands and one historian has estimated that the Flemish/Dutch population had dropped to just over a thousand by 1582. The likelihood, however, is that although numbers were decreasing the decline was not as great as this, and that numbers were nearer 1,600 to 2,000 in 1582." The Population of Sandwich From Elizabeth I To The Civil War. Accessed August 1, 2019."

- ^ [2] The Elizabethan Strangers. BBC. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "Flemish weavers came and settled in North Walsham in the 13th and 14th centuries." Tour Norfolk. Accessed August 3, 2019.

- ^ "By the fifteenth century a small community of weavers and farmers was established and it is believed that this was the origin of Whitefield" Bury Metropolitan Borough Council. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- ^ "They (Flemish) tended to settle in a tightly packed strip of woods between Green Bay and Sturgeon Bay." Wisconsin Historical Society. Accessed August 3, 2019.

- ^ [3] The Flemish In Wisconsin, Jeanne and Les Rentmeester, 1985.

External links

edit- Media related to Flemish people at Wikimedia Commons