The flocculus (Latin: tuft of wool, diminutive) is a small lobe of the cerebellum at the posterior border of the middle cerebellar peduncle anterior to the biventer lobule. Like other parts of the cerebellum, the flocculus is involved in motor control. It is an essential part of the vestibulo-ocular reflex, and aids in the learning of basic motor skills in the brain.

| Flocculus | |

|---|---|

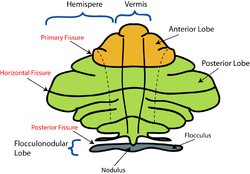

Schematic representation of the major anatomical subdivisions of the cerebellum. Superior view of an "unrolled" cerebellum, placing the vermis in one plane. | |

Anterior view of the cerebellum. ("Flocculus" labeled at upper right.) | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Cerebellum |

| System | Vestibular |

| Artery | AICA |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

It is associated with the nodulus of the vermis; together, these two structures compose the vestibular part of the cerebellum.

At its base, the flocculus receives input from the inner ear's vestibular system and regulates balance. Many floccular projections connect to the motor nuclei involved in control of eye movement.

Structure

editThe flocculus is contained within the flocculonodular lobe which is connected to the cerebellum. The cerebellum is the section of the brain that is essential for motor control. As a part of the cerebellum, the flocculus plays a part in the vestibulo-ocular reflex system, a system that controls the movement of the eye in coordination with movements of the head.[1] There are five separate “zones” in the flocculus and two halves, the caudal and rostral half.

Circuitry of the flocculus

editThe flocculus has a complex circuitry that is reflected in the structure of the zones and halves. These "zones" of the flocculus refer to five separate groupings of Purkinje cells that project to different areas of the brain. Depending upon where stimulus occurs in the flocculus, signals can be projected to very different parts of the brain. The first and third zones of the flocculus project to the superior vestibular nucleus, the second and fourth zones project to the medial vestibular nucleus, and the fifth zone projects to the interposed posterior nucleus, a part of the cerebellum.[2]

The anatomy of the flocculus shows that it is composed of two disjointed lobes or halves. The “halves” of the flocculus refer to the caudal half and the rostral half, and they indicate from where fiber projections are received and the path in which a signal travels.[3] The caudal half of the flocculus receives mossy fiber projections mainly from the vestibular system and tegmental pontine reticular nucleus, an area within the floor of the midbrain that affects the axonal projections or images received by the cerebellum. Vestibular inputs are also carried through climbing fibers that project into the flocculus, stimulating Purkinje cells. Leading research would suggest that climbing fibers play a specific role in motor learning.[4] The climbing fibers then send the image or projection to the part of the brain that receives electrical signals and generates movement. From the midbrain, corticopontine fibers carry information from the primary motor cortex.[1] From there, projections are sent to the ipsilateral pontine nucleus in the ventral pons, both of which are associated with projections to the cerebellum. Finally, pontocerebellar projections carry vestibulo-occular signals to the contralateral cerebellum via the middle cerebellar peduncle.[5] The rostral half of the flocculus also receives mossy fiber projections from the pontine nuclei; however, it receives very little projection from the vestibular system.

Function

editThe flocculus is a part of the vestibulo-ocular reflex system and is used to help stabilize gaze during head rotation about any axis of space. Neurons in both the vermis of cerebellum and flocculus transmit an eye velocity signal that correlates with smooth pursuit.

Flocculus role In learning basic motor functions

editThe idea that the flocculus is involved in motor learning gave rise to the “flocculus hypothesis.” This hypothesis argues that the flocculus plays a key role in the vestibulo-ocular system, most importantly the ability for the vestibular system to adapt to a shift in the visual field.[3] The learning of basic motor skills, including walking, balancing, and the ability to sit up, can be attributed to early patterns and pathways associated with the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and the pathways formed in the cerebellum that contribute to the learning of basic motor skills. The flocculus appears to be included in a VOR pathway that aids in the adaptation to a repeated shift in the visual field.[4] A shift in the visual field affects an individual's spatial recognition. The leading research would suggest that the flocculus aids in the synchronization of eye and motor functions after a visual shift occurs in order for the visual field and the motor skills to function together. If this shift is repeated the flocculus essentially trains the brain to fully readjust to these repeated stimuli.[6]

Location

editConstituted by two disjointed-shaped lobes, the flocculus is positioned within the lowest level of the cerebellum. There are three main subdivisions in the cerebellum and the flocculus is contained within the most primitive the vestibulocerebellum.[1]

Its lobes are linked through a circuit of neurons connecting to the vermis, the medial structure in the cerebellum. Extensions leave the base of the follucular's lobes which then connect to the spinal cord. The cerebellum, which houses the flocculus, is located in the back and at the base of the human brain, directly above the brainstem.[7]

Clinical significance

editThe flocculus is most important for the pursuit of movements with the eyes. Lesions in the flocculus impair control of the vestibulo-ocular reflex, and gaze holding also known as vestibulocerebellar syndrome.[8] The deficits observed in patients with lesions to this area resemble dose-dependent effects of alcohol on pursuit movements.[9] Bilateral lesions of the flocculus reduce the gain of smooth pursuit, which is the steady tracking of a moving object by the eyes. Instead, the bilateral lesions of the flocculus result in saccadic pursuit, in which smooth tracking is replaced by simultaneous rapid movements, or jerking motions, of the eye to follow an object toward the ipsilateral visual field. These lesions also impair the ability to hold the eyes in the eccentric position, resulting in gaze-evoked nystagmus toward the affected side of the cerebellum.[8] Nystagmus is the constant involuntary movements of the eyes; a patient can have either horizontal nystagmus (side-to-side eye movements), vertical nystagmus (up and down eye movements), or rotary nystagmus (circular eye movements).[8] The flocculus also plays a role in keeping the body oriented in space. A lesion in this area will result in ataxia, a neurological disorder that results in the deterioration of the coordination of muscle movements, and unsteady bodily movements such as swaying and staggering.[7]

Associated conditions

editThe conditions and systems associated with floccular loss are considered to be a subset of a vestibular disease. Some symptoms of common vestibular diseases include: head tilting, an inability to stand, ataxia, dizziness, vomiting and strabismus. Because of the flocculus’ role in the vestibular system, the inner ear, equilibrioception, and both peripheral and central vision is affected by any loss or damage to the flocculus. These systems are affected because damage to the flocculus prevents any changes from being stored in regards to visual and motor communication, meaning that although the VOR is still intact these systems are unable to store changes in gain or eye movement as the head is rotated back and forth.[10]

Additional images

editThis gallery of anatomic features needs cleanup to abide by the medical manual of style. |

-

Human cerebellum anterior view

-

Cerebellum. Inferior surface.

-

Cerebellum. Inferior surface.

-

Cerebellum. Inferior surface.

References

edit- ^ a b c Purves, Dale, ed. (2012). Neuroscience Fifth Edition. Sutherland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-646-5.[page needed]

- ^ De Zeeuw, C. I.; Wylie, D. R.; Digiorgi, P. L.; Simpson, J. I. (1994). "Projections of individual purkinje cells of identified zones in the flocculus to the vestibular and cerebellar nuclei in the rabbit". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 349 (3): 428–47. doi:10.1002/cne.903490308. PMID 7852634. S2CID 21175287.

- ^ a b Ito, M (1982). "Cerebellar Control of the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex--Around the Flocculus Hypothesis". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 5: 275–96. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.05.030182.001423. PMID 6803651.

- ^ a b Lisberger, S. (1988). "The neural basis for learning of simple motor skills". Science. 242 (4879): 728–35. Bibcode:1988Sci...242..728L. doi:10.1126/science.3055293. PMID 3055293.

- ^ McDougal, David; Van Lieshout, Dave; Harting, John. "Pontine Nuclei and Middle Cerebellar Penduncle". Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Broussard, Dianne M.; Titley, Heather K.; Antflick, Jordan; Hampson, David R. (2011). "Motor learning in the VOR: The cerebellar component". Experimental Brain Research. 210 (3–4): 451–63. doi:10.1007/s00221-011-2589-z. PMID 21336828. S2CID 31829859.

- ^ a b Reitan, Ralph M.; Wolfson, Deborah (1998). A Clinical Guide for Neuropsychologists. Tuscan, Arizona: Neuropsychology Press.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Benarroch, Eduardo (2006). Basic Neurosciences with Clinical Applications. Philadelphia: Butterworth–Heinemann.[page needed]

- ^ Per, Brodal (1998). The Central Nervous System Structure and Function (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Dean, Paul; Porrill, John (2008). "Oculomotor anatomy and the motor-error problem: The role of the paramedian tract nuclei". In Kennard, Christopher; Leigh, R. John (eds.). Using Eye Movements as an Experimental Probe of Brain Function - A Symposium in Honor of Jean Büttner-Ennever. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 171. pp. 177–86. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00624-9. ISBN 978-0-444-53163-6. PMID 18718298.

External links

edit- Atlas image: n2a7p4 at the University of Michigan Health System

- NIF Search - Flocculus via the Neuroscience Information Framework