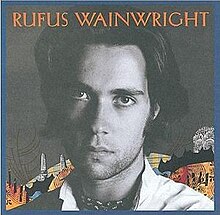

Rufus Wainwright is the debut studio album by Canadian-American singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright, released in the United States on May 19, 1998, through DreamWorks Records.[1] It was produced by Jon Brion, with the exception of "In My Arms", which was produced and mixed by Pierre Marchand, and "Millbrook" and "Baby", which were produced by Brion and Van Dyke Parks. Lenny Waronker was the executive producer.

| Rufus Wainwright | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | May 19, 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1996–1997 | |||

| Length | 53:26 | |||

| Label | DreamWorks | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Rufus Wainwright chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

25th Anniversary Edition cover | ||||

Wainwright was signed to the DreamWorks label in 1996 after Waronker heard the demo tape he recorded with Marchand. Over the course of two years, Wainwright and Brion recorded 56 songs on 62 rolls of tape at a cost that exceeded $700,000. These were then narrowed down to twelve tracks for the album. No singles were released from Rufus Wainwright, though Sophie Muller directed the music video for "April Fools", which featured Wainwright in Los Angeles attempting to prevent the deaths of opera heroines. To support the album, Wainwright toured throughout the United States and Canada following its release.

Overall, reviews for the album were positive. Though it failed to chart in any country, Wainwright reached number 24 on Billboard's Top Heatseekers chart (which highlights sales by new and developing musical recording artists) and Rolling Stone named Wainwright the Best New Artist of 1998. Rufus Wainwright also earned him recognition from the Gay & Lesbian American Music Awards, the GLAAD Media Awards, and the Juno Awards. The album was released in Japan with the bonus track "A Bit of You", and later in 2008 in LP form through the record label Plain Recordings.

Background

editWainwright, born into a musical family which included parents Loudon Wainwright III and Kate McGarrigle and sister Martha Wainwright, began touring in his early teens with his family throughout Canada, Europe, and the United States. At age fourteen, his song "I'm a Runnin'", written for the 1988 Canadian film Tommy Tricker and the Stamp Traveller, earned him a Genie Award nomination for Best Achievement in Music – Original Song and a Juno Award nomination in 1990 for Most Promising Male Vocalist of the Year.[2][3]

Wainwright attended McGill University in Montreal for a short time to study Classical music composition. With his mother's support, he began writing pop songs and learned how to play guitar. Wainwright started performing at the night club Sarajevo, and eventually recorded a demo tape with record producer Pierre Marchand, a family friend, who had worked with Kate and Anna and who later produced Wainwright's second studio album Poses. Songs were recorded at Marchand's studio in Morin-Heights, Quebec, and no edits were made to the simple live tunes.[4] The tape impressed Wainwright's father, who passed the songs along to producer Van Dyke Parks, who in turn presented them to DreamWorks executive Lenny Waronker.[5][6] Waronker had signed McGarrigle to Warner Bros. Records in the 1970s.[7] Wainwright acknowledged that having musicians as parents gave him a "foot in the door", but attributed his success to hard work.[5]

Development

editThe songs are very demanding musically, and they really require someone who knows what they're doing ... It's very orchestrated, very produced, very big. I was a little worried about that at first, but I'm really happy with it now. It's the way I wanted it to be.

Wainwright was signed to DreamWorks in 1996. Waronker paired him with producer Jon Brion, and together they spent "most of 1996 and 1997" recording 56 songs on 62 rolls of tape.[9] Costs for the recording sessions reached between $700,000 and $1,000,000.[7] Wainwright admitted that he and Brion took their time recording the album in Los Angeles, and considered the extended time a "blessing" and "luxury", claiming that "most people have two weeks to record their first album".[8] According to Wainwright, Waronker "didn't care how long it took, as long as we were doing good work."[9] Waronker was pleased with the final product, and he and Wainwright agreed on the twelve tracks that made up the album.[10]

Songs on the album were produced by Brion, except "In My Arms" was produced and mixed by Marchand, and "Millbrook" and "Baby" were produced by Brion and Van Dyke Parks.[11] Waronker served as the executive producer. Rufus Wainwright was recorded mostly in Los Angeles studios—Ocean Way studios 3 and 7, Sunset Sound Factory, Sunset Sound, Media Vortex, Hook Studios, Groove Masters, Red Zone, Sony, The Palindrome Recorder, and NRG Recording Services—although recording also took place in Marchand's Wild Sky in Morin-Heights, Quebec.[9][11] Parks conducted his orchestrations at Studio B in the Capitol Studios complex.[9]

Wainwright and Brion did not always get along, the latter admitting to The New York Times: "Rufus had all these beautiful songs but every time the vocals would kick in, he'd write some complicated keyboard part so you couldn't hear them. He wasn't interested in listening to ideas about simplifying arrangements."[9] The duo, with Ethan Johns, also contributed the songs "Le Roi D'Ys" and "Banks of the Wabash" (both "contemporary" cover versions) to the 1997 soundtrack to the film The Myth of Fingerprints.[12] Johns later considered "Le Roi D'Ys", recorded in around six hours, to be one of his favorite tracks by Wainwright.[10]

Rufus Wainwright was released on May 19, 1998, through DreamWorks. Following the album's release, which earned him mostly positive reviews, Wainwright contributed to The McGarrigle Hour, a 1998 album by Kate & Anna McGarrigle featuring family members Loudon and Martha along with singers Emmylou Harris and Linda Ronstadt.[13] In December 1998, Wainwright appeared in a Gap television advertisement in which he performed Frank Loesser's 1947 song "What Are You Doing New Year's Eve?"[14][15] In 1999, he was one of several featured artists promoted by Best Buy as part of a campaign to promote young talent.[16] The album was re-issued in 2008 in LP form through the record label Plain Recordings.[1]

Songs

editThe "neo-operatic" opening track "Foolish Love", arranged by Van Dyke Parks, was described by AllMusic contributor Matthew Greenwald as a "lush, orchestral-soaked ballad, with incredible strings".[17] He asserted that Wainwright's lyrics took the form of a letter to himself, defining his goals and "sense of purpose".[17] The song "Danny Boy", with its "fabulous wordplay that stays literate and easy to understand at the time", contains "subtle" horn lines and sampled percussion. The song alludes to Wainwright's homosexuality, which Greenwald considered a "brave move".[18] According to biographer Kirk Lake, "Danny Boy" is a companion piece to "Foolish Love" and together they represent the start and end of a relationship between a gay and a straight man.[19] Danny, the straight "drug-addled" title figure with whom Wainwright had a three-year relationship, is the subject of both songs in addition to others on the album; he appears in the album's collage artwork.[19][20] Wainwright sings of being so blinded by love that he fails to notice the "ship with eight sails" threatening to come around the bend, a reference to Bertolt Brecht's 1928 musical The Threepenny Opera.[19]

The chorus in "April Fools" begins with an "unusually upbeat attitude" and was considered by Greenwald to be the most accessible track on the album.[21] The song showcases Jim Keltner's drum performance as well as Wainwright's piano playing.[21] Driven by Wainwright's guitar playing, "In My Arms" was described by Greenwald as a "forlorn", Spanish-influenced ballad that sounded as though it "could have been recorded in France in the 1920s".[22] The song "Millbrook" is an ode to his boarding school compatriots.[23] Wainwright has admitted to being "upset and drunk" when recording the final take.[24] "Baby", which has been considered one of the most melancholic songs on the album, contains "oddly placed" and "slightly quirky" major seventh chords. Greenwald called the lyrics "a stream-of-consciousness pleasure, relating the confusing and intoxicating emotions of young love".[25]

"Beauty Mark" is an ode to Wainwright's mother, the title referring to the beauty mark above her lip.[26] The song is one of the few up-tempo tracks on the album and contains multiple keyboard overdubs by Brion.[26] Chris Yurkiw of the Montreal Mirror considered the track to be the most moving love song on the album, with an "overt and open-hearted" reference to his homosexuality: "I may not be so manly, but still I know you love me."[27] Wainwright's Summer Stage performance of "Beauty Mark" appears on his 2005 DVD All I Want.[28] In "Barcelona", Wainwright recalls a love affair that took place in the city of the same name.[29] The song is loosely about AIDS and contains the Italian language lyric "Fuggi, regal fantasima", taken from Giuseppe Verdi's opera Macbeth. According to Wainwright, the line appears in a scene when "Macbeth is going mad and sees the ghost, and in [Wainwright's] mind the ghost was AIDS."[27] "Matinee Idol" is about the rise and fall of an entertainment figure, inspired by the death of actor River Phoenix.[30][31] According to Greenwald, the musical song has a "1920s, cabaret musical feel".[30]

"Damned Ladies" is a slow ballad about the "beloved yet doomed ladies of opera".[32] Wainwright said the following of "Damned Ladies", which contains references to nine opera heroines: "In the song, I lament how these women are constantly dying brutal deaths, which I can see coming but cannot stop. It gets me every time."[19] Greenwald described "Sally Ann" as a 1920s love ballad of "lost love and emotional regret".[33] The melody in "Imaginary Love", the album's closing track, contains sixth and major seventh chords.[34]

In Japan, the album was released with the bonus track "A Bit of You".[35] In May 2023, the album's 25th anniversary, a remastered version was released with songs previously released on the 2011 box set House of Rufus plus three session outtakes. The track list consists of the original album plus the tracks: "Hankering", "Saint James Infirmary", "More Wine", "Fame Into Love Into Death", "One More Chance", "A Bit of You", "Dreams and Daydreams", "Miss Otis Regrets", "So Fine", and "Come". For the album's cover, Wainwright recreated his original art using a photograph of him at age 50.[36]

Promotion

editWainwright acknowledged that his debut album was "not a single driven album"; no singles were released from it.[37] To promote the album, a music video was produced for the song "April Fools".[38] Directed by Sophie Muller, the video features Wainwright in Los Angeles "amidst a clique of classic opera characters" such as Madame Butterfly, attempting to prevent each of them from committing suicide. However, in each instance he arrives too late.[37] The video also contains cameo appearances by No Doubt's Gwen Stefani, a friend of Muller's, and Hole bassist Melissa Auf der Maur, a high school acquaintance and former roommate of Wainwright's. Part of the video was filmed in Stefani's house.[37]

Wainwright performed "Beauty Mark" on Today, the American morning news and talk show.[39] He also taped an episode of MTV's television program 120 Minutes to promote the album, which aired on March 28, 1999.[40] An advertisement in Billboard promoting the album also referred to appearances on CBS News Sunday Morning, Late Night with Conan O'Brien, Late Show with David Letterman, and Sessions at West 54th.[41]

In the year prior to the album's release, Wainwright opened for artists such as Barenaked Ladies and Sean Lennon. On March 1, 1999, Wainwright began his first tour as a headlining act in Hoboken, New Jersey. During that month, Wainwright toured throughout New England and the mid-Atlantic states, Ontario (Ottawa and Toronto), Quebec (Montreal), the southern United States (Nashville, and Atlanta), and the midwestern United States (Cincinnati, Chicago, and Pontiac).[37] Wainwright continued to tour throughout the month of April before heading to Europe.[37] Stops were mostly along the West Coast, including four in California, Portland, Oregon, and Seattle. Three concerts were also held in western Canada, including Vancouver, Edmonton, and Calgary.[42]

Critical reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [1] |

| The Baltimore Sun | [43] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[44] |

| Houston Chronicle | [45] |

| Los Angeles Times | [46] |

| NME | 7/10[47] |

| Rolling Stone | [48] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [49] |

| Spin | 7/10[50] |

| The Village Voice | B+[51] |

Reception of the album was positive. Speaking of second-generation artists emerging around the same time, AllMusic's Jason Ankeny wrote that Wainwright "deserves to be heard regardless of his family tree". Furthermore, Ankeny complimented the musician for his songwriting abilities and his "knack for elegantly rolling piano melodies and poignantly romantic lyrics".[1] Music journalist Robert Christgau characterized Wainwright as a "mind-boggling original" whose talent is "too big to let pass".[51] Los Angeles Times critic Marc Weingarten found that the "abiding, uncynical" view of love expressed in Wainwright's lyrics does not come off as "mawkish" due to his considerable skills as a songwriter and arranger.[46] NME reviewer John Mulvey called the album "floridly impersonal" and "grandiosely arranged", but also criticized Wainwright for being "too overwrought and naff".[47] Greenwald complimented Martha's backing vocals on the song "In My Arms", as well as Parks' "positively sterling" string arrangement on "Millbrook".[22][23] Furthermore, he praised the vocal duet between Rufus and Martha on "Sally Ann", claiming that a similar sibling performance had not been heard since the Everly Brothers.[33] The album's cabaret elements and 1970s singer-songwriter style drew comparisons to Cole Porter and Joni Mitchell.[6] Josh Kun of Salon wrote that Wainwright poetically incorporated "foolish love and fantasy love, healing love and destructive love and love that makes you want to lose your sense of self just so you can find it again." Kun asserted that the songs were "built on a similar set of angled melodies and hairpin turns of phrase", and that each "succeeds as its own distinctly intimate portrait of emotion and desire."[52]

Ann Powers, music critic for The New York Times, included the album at number five on her list of the Top 10 albums of 1998.[53] The album was also included in The Village Voice's 1998 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll, which combined ballots from 496 critics.[37][54] Rufus Wainwright was nominated four times by the Gay & Lesbian American Music Awards, an organization that provided the foundation for the recognition of the excellence of LGBT artists.[55] Wainwright received the award for Best New Artist, the album was nominated for Album of the Year, and "April Fools" was nominated for Video of the Year and Best Pop Recording.[56] The GLAAD Media Awards, created by the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) to recognize and honor the mainstream media for their fair and accurate representations of the LGBT community, presented Wainwright with the award for Outstanding Music Album.[57] At the Juno Awards of 1999, Rufus Wainwright earned Wainwright the Juno Award for Best Alternative Album.[58]

Commercial reception

editAlbum sales were limited—by March 1999 only 35,000 copies had been sold.[40][59] In 2001, Michael Giltz of The Advocate wrote that Wainwright's biggest sales boost came from the Gap advertisement rather than radio play.[60] Despite low sales, Wainwright reached number 24 on Billboard's Top Heatseekers chart, and Rolling Stone named him 1998's Best New Artist.[61][62] The January 19, 1999 CMJ New Music Report showed that Rufus Wainwright spent nine weeks on CMJ Radio 200 reaching a peak position of number 52, five weeks on CMJ Code Radio reaching a peak position of number 42, as well as nine weeks on CMJ Triple A reaching a peak position of number 9.[63]

Track listing

editAll songs written by Wainwright. Track listing adapted from AllMusic.[1]

- "Foolish Love" – 5:46

- "Danny Boy" – 6:12

- "April Fools" – 5:00

- "In My Arms" – 4:08

- "Millbrook" – 2:11

- "Baby" – 5:13

- "Beauty Mark" – 2:14

- "Barcelona" – 6:53

- "Matinee Idol" – 3:08

- "Damned Ladies" – 4:07

- "Sally Ann" – 5:01

- "Imaginary Love" – 3:28

Personnel

edit- Jon Brion – Chamberlin (1), accordion (1), marimba (1,9), vibes (1,10), bass guitar (2,9,12), baritone guitar (2,3,11), optigan (2), acoustic guitar (2,3,12), electric guitar (3), background vocals (3,12), percussion (3,8), timpani (7), crotales (7), celeste (7,10), temple blocks (7), assorted bells (7), tuned toms (8), mandolin (9), drums (9), tack piano (10)

- Randy Brion – horn arrangement (2,11), conductor (2,11)

- Yves Desrosiers – acoustic guitar (4), electric guitar (4), slide bass (4)

- Marty Grebb – alto saxophone (9)

- Glen Hollman – upright (1,7,12), mandolin bass (10)

- Jim Keltner – drums (1-3,7,11,12)

- Pierre Marchand – bass guitar (4), keyboards (4)

- Van Dyke Parks – string arrangement (1,5,6), conductor (1,5,6)

- Ash Sood – drums (4), percussion (4)

- Benmont Tench – piano (3,11), Hammond organ (11)

- Martha Wainwright – background vocals (3,4,11)

- Rufus Wainwright – vocals (1-12), background vocals (3), piano (1,2,5-7,10,12), Chamberlin (1,8,9), tack piano (1,2,9), acoustic guitar (3,8,10,11), castanets (8), half-speed piano (1), humming (10)

Credits adapted from AllMusic and the album liner notes.[1][11]

See also

edit- A Singer Must Die (2010), by Art of Time Ensemble featuring Steven Page (includes a cover version of "Foolish Love")[64]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Ankeny, Jason. "Rufus Wainwright – Rufus Wainwright". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "Canada's Awards Database – 10th Genies – Best Original Song". Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "Juno Awards Database". Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on June 20, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2011. Note: User must define search parameters as "Rufus Wainwright".

- ^ Lake 2010, p. 70

- ^ a b Booth, Philip (August 7, 1998). "Wainwright steps out of his parents' shadows". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. The New York Times Company. p. 8. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Farber, Jim (May 17, 1998). "Pop Stars: The Next Generation Rufus Wainwright, Loudon's Son, Makes a Breathtaking Debut". Daily News. New York City: Mortimer Zuckerman. Retrieved March 20, 2011. [dead link]

- ^ a b Plasketes, George (2009). B-sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present. Ashgate Publishing. p. 159. ISBN 9780754665618. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Yurkiw, Chris (July 31, 1997). "All the (Wainw)right moves: Piano man Rufus Wainwright finishes his debut album in L.A." Montreal Mirror. Quebecor. Archived from the original on January 12, 2004. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Lake 2010, p. 105

- ^ a b Lake 2010, p. 106

- ^ a b c Rufus Wainwright (CD insert). Rufus Wainwright. DreamWorks Records. 1998.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Cater, Darryl. "The Myth of Fingerprints". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "The McGarrigle Hour". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Loesser, Susan (2000). A Most Remarkable Fella: Frank Loesser and the Guys and Dolls in His Life: A Portrait by His Daughter. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 61. ISBN 9780634009273. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Farber, Jim (December 17, 1998). "Rufus Wainwright Romances Audience with Heartfelt Style". Daily News. New York City: Mortimer Zuckerman. Retrieved March 19, 2011. [dead link]

- ^ Bauder, David (March 28, 1999). "Rising musicians getting lost in crowd". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. p. 7B. Retrieved March 20, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "Foolish Love: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Greenwald, Matthew. "Danny Boy: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Lake 2010, p. 72

- ^ Schwartz, Deb (January 1999). "The Rufus On Fire". Out. 7 (7). Here Media: 66. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "April Fools: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "In My Arms: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "Millbrook: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Kot, Greg (July 17, 1998). "New Out Of Old". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Greenwald, Matthew. "Baby: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "Beauty Mark: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on November 10, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Yurkiw, Christ (1998). "Drama queen: Piano man Rufus Wainwright says he downplays being gay". Montreal Mirror. Quebecor. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "All I Want". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Greenwald, Matthew. "Barcelona: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "Matinee Idol: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Powers, Ann (March 13, 1998). "Following His Troubadour Lineage, but Cutting a New Path". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ Greenwald, Matthew. "Damned Ladies: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Matthew. "Sally Ann: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Greenwald, Matthew. "Imaginary Love: Song Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Rufus Wainwright (Japan Bonus Tracks)". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ Brodsky, Rachel (May 19, 2023). "Rufus Wainwright Releases 25th Anniversary Reissue of Debut Album With Previously Unreleased Outtakes". Stereogum. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Rufus Wainwright Kicks Off Tour, Explains Video Cameos". MTV. March 2, 1999. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright – April Fools". Geffen Records. 1998. Archived from the original on March 21, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Morris, Bob (June 24, 2001). "Out and Proud, But Hardly Pectorally Correct". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ a b "Newsmakers". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Lewiston, Idaho. March 8, 1999. p. 10A. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 7. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. February 13, 1999. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2011. Note: Advertisement.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright, Peter, Paul and Mary ..." VH1. April 14, 1999. Retrieved March 23, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Considine, J. D. (June 18, 1998). "Rufus Wainwright: Rufus Wainwright (Dreamworks 50039)". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Browne, David (May 22, 1998). "Sean Lennon: Into the Sun / Rufus Wainwright: Rufus Wainwright". Entertainment Weekly. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Wiegand, David (May 17, 1998). "A Son of Singers Has His Own Flair". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Weingarten, Marc (May 29, 1998). "Rufus Wainwright, 'Rufus Wainwright,' DreamWorks". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Mulvey, John (August 12, 1998). "Rufus Wainwright – Rufus Wainwright". NME. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Chonin, Neva (May 18, 1998). "Rufus Wainwright: Rufus Wainwright". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Randall, Mac (2004). "Rufus Wainwright". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 854. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (July 1998). "Rufus Wainwright: Rufus Wainwright". Spin. 14 (7): 122–25. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (June 2, 1998). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Kun, Josh (May 20, 1998). "New release roundup". Salon.com. Salon Media Group. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ Powers, Ann (January 6, 1999). "Best Memories Of a Musical Year Full of Echoes". The New York Times. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "The 1998 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". RobertChristgau.com. March 2, 1999. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "Barnes, Rufus Wainwright Lead GLAMA Nominations". CMJ New Music Report. 57 (610). CMJ Network: 5. March 22, 1999. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ Doyle, JD. "The Gay & Lesbian American Music Awards". Queer Music Heritage (KPFT). Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "GLAAD Announces Nominees of 10th Anniversary Media Awards" (Press release). Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. January 20, 1999. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2011. Note: Press release hosted by the Queer Resources Directory.

- ^ "Juno Awards Database". Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011. Note: User must define search parameters as "Rufus Wainwright".

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright: following road less traveled". Star-News. Vol. 132, no. 124. Wilmington, North Carolina: The New York Times Company. March 8, 1999. p. 2A. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Giltz, Michael (May 8, 2001). "The World According to Rufus". The Advocate: 38. Archived from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2011. Note: Source also confirms the album's inclusion in The Village Voice's 1998 Pazz & Jop poll.

- ^ Vary, Adam (August 28, 2001). "Singer Rufus Wainwright aims for the mainstream". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "Rufus Wainwright: Charts & Awards". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "CMJ's Top 30 Editorial Picks". CMJ New Music Report. 57 (601). CMJ Network: 3. January 11, 1999. Archived from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "A Singer Must Die". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- Works cited

- Lake, Kirk (2010). There Will Be Rainbows: A Biography of Rufus Wainwright. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-198846-2. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

External links

edit- Review by Saul Austerlitz of The Yale Herald (January 15, 1999)