This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (May 2023) |

Operation Ripper, also known as the Fourth Battle of Seoul, was a United Nations (UN) military operation conceived by the US Eighth Army, General Matthew Ridgway, during the Korean War. The operation was intended to destroy as much as possible of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) and Korean People's Army (KPA) forces around Seoul and the towns of Hongch'on, 50 miles (80 km) east of Seoul, and Chuncheon, 15 miles (24 km) further north. The operation also aimed to bring UN troops to the 38th Parallel. It followed upon the heels of Operation Killer, an eight-day UN offensive that concluded February 28, to push PVA/KPA forces north of the Han River. The operation was launched on 6 March 1951 with US I Corps and IX Corps on the west near Seoul and Hoengsong and US X Corps and Republic of Korea Army (ROK) III Corps in the east, to reach the Idaho Line, an arc with its apex just south of the 38th Parallel in South Korea.

| Operation Ripper | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean War | |||||||||

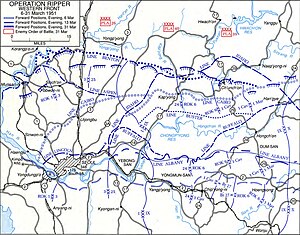

Operation Ripper western front map | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Total unknown 3,220 wounded[2] | 7,151 known dead; Thousands killed, wounded and captured | ||||||||

Operation Ripper was preceded by the largest artillery bombardment of the Korean War. In the middle, the US 25th Infantry Division quickly crossed the Han and established a bridgehead. Further to the east, IX Corps reached its first phase line on 11 March. Three days later the advance proceeded to the next phase line. During the night of 14–15 March, elements of the ROK 1st Infantry Division and the US 3rd Infantry Division liberated Seoul, marking the fourth and last time the capital changed hands since June 1950. The PVA/KPA forces were compelled to abandon it when the UN approach to the east of the city threatened them with encirclement.

Following the recapture of Seoul the PVA/KPA forces retreated northward, conducting skilful delaying actions that utilized the rugged, muddy terrain to maximum advantage, particularly in the mountainous US X Corps sector. Despite such obstacles, Operation Ripper pressed on throughout March. In the mountainous central region, US IX and US X Corps pushed forward methodically, IX Corps against light opposition and X Corps against staunch enemy defenses. Hongch'on was taken on the 15th and Chuncheon secured on the 22nd. The capture of Chuncheon was the last major ground objective of Operation Ripper.

UN forces had advanced north an average of 30 miles (48 km) from their start lines. However, while the Eighth Army had occupied their principal geographic objectives, the goal of destroying PVA forces and equipment had again proved elusive. More often than not, the PVA/KPA forces withdrew before they suffered extensive damage. Chuncheon, a major PVA/KPA supply hub, was empty by the time UN forces finally occupied it. As the UN troops ground forward, they were constantly descending sharp slopes or ascending steep heights to attack enemy positions that were sometimes above the clouds. By the end of March, US forces reached the 38th Parallel.

Background

editAs Operation Killer had entered its final week with limited results already predictable, Ridgway published plans for another attack, again with the main effort in his central zone, but with all units on the Eighth Army front involved. As in Operation Killer, the primary purposes of the attack, which Ridgway called Operation Ripper, were to destroy PVA/KPA forces and equipment and to interdict their attempts to organize an offensive. A secondary purpose was to outflank Seoul and the area north of the city as far as the Imjin River. Aware of UN commander General Douglas MacArthur’s interest in recapturing Seoul, but preferring to avoid a direct assault across the Han River into the capital (although plans had been prepared for such an operation), Ridgway hoped to gain a position from which he could take Seoul and the ground to the north by a flanking attack from the east or simply by posing a threat that would induce enemy forces to withdraw from that area.[3]

Ridgway published the Ripper plan on 1 March but deferred setting an opening date because of forward area supply shortages, particularly in food, petroleum products, and ammunition. The shortages resulted partially from conscious efforts during February, especially during the Chinese Fourth Phase Offensive in mid-February, to hold down stockpiles in forward dumps as a hedge against losses through forced abandonment or destruction. In addition, as stocks were expended in the Killer advance, the damage to roads, rail lines, bridges, and tunnels caused by the rains and melting ice and snow severely hampered resupply. Before setting a date for the operation Ridgway wanted a five-day level of supplies established at all forward points. The best estimate at the beginning of March was that this level could be reached in about five days.[3]: 311

Regardless of success in meeting this logistical requirement, Ridgway intended to cancel the operation if in the time taken to raise forward supply levels new intelligence disclosed clear evidence of an imminent PVA/KPA attack. Neither the capture of new ground nor the retention of ground currently held were essential features of Eighth Army operations as Ridgway conceived them. "Terrain," he maintained, "is merely an instrument... for the accomplishment of the mission here," that of inflicting maximum losses on the PVA/KPA at minimum cost while maintaining major units intact. Intelligence indicated that those forces giving ground before the Killer advance in the IX and X Corps' zones were moving into defensive positions just above the Arizona Line. Eighth Army intelligence officer Colonel Tarkenton, believed these forces would tie in with the existing PVA/KPA front tracing the north bank of the Han River in the west and passing through the ridges above Route 20 in the east. Lending support to this judgment, the PVA 39th Army had moved up on the line in front of IX Corps, and the KPA III Corps, less its 3rd Infantry Division, had entered the line before X Corps. Thus, as of 1 March six PVA armies and four KPA corps were arrayed between Seoul and the spine of the Taebaek Mountains. On the 1st, as he had earlier, Tarkenton carried the PVA 37th Army in his enemy order of battle, locating it immediately behind the center of the PVA/KPA front in the vicinity of Chuncheon. In his earlier estimate he tentatively had placed the 43rd Army in the same area, but had since decided that this unit was not in Korea at all. Tarkenton now also had reports that two PVA armies, the 24th and 26th, had moved south from the Hungnam-Wonsan region to a central assembly just above the 38th Parallel north of Chuncheon. Thus three reserve armies might be immediately available for offensive operations in the central region. To add substance to this possibility, agents recently returning from behind enemy lines brought back reports that the PVA/KPA high command at one time had planned to open an offensive on 1 March, then had postponed the opening date to the 15th. During interrogation, recently taken prisoners of war partially substantiated the agent reports by stating that their forces were preparing to launch an offensive in the Eighth Army's central zone early in March. It also now appeared that the KPA VI Corps, one of the units that had withdrawn into Manchuria the past autumn, had returned to Korea and was moving toward the front in the west. At last report the VI Corps, or a part of it, was approaching the 38th Parallel northwest of Seoul and thus was near enough to join an offensive. Tarkenton concluded, however, that although the PVA/KPA high command was preparing an offensive, its opening was not imminent. He reached that conclusion mainly on grounds that the bulk of their reserves were too far north for early employment.[3]: 311–313

Amid efforts to acquire fuller information on PVA/KPA preparations and plans, Ridgway arranged an amphibious demonstration in the Yellow Sea in an attempt to fix PVA/KPA reserves and to distract their attention from the central zone in which the main Ripper attack was to be made. Minesweepers of Task Force 95 began the demonstration with sweeps along the west coast and into the Taedong River estuary in the vicinity of Chinnamp’o. A cruiser and destroyer contingent followed to bombard pretended landing areas. Troop and cargo ships next left Inchon, steamed part way up the coast, then reversed course. On 5 March the same ships made an ostentatious departure from Inchon to continue the illusion of an impending amphibious landing. In the Sea of Japan, Task Force 95 had placed the Wonsan area under bombardment in February and continued the campaign into March. This bombardment, coupled with the occupation of an offshore island by a small party of South Korean Marines, added to the impression of imminent landing operations. Ridgway had learned that two recently federalized National Guard infantry divisions, the 40th and 45th, were soon to leave the United States for duty in Japan. In an attempt to enlarge the amphibious threat, he proposed to MacArthur that the departure of the divisions be publicized and a deception plan be developed to indicate that the two units would make an amphibious landing in Korea. Extending the idea further, Ridgway also proposed creating the illusion of forthcoming airborne operations by having three replacement increments of 6,000 each put on 82nd Airborne Division patches after arriving in Japan and wear them until they reached Korea. He made this second proposal on the basis of intelligence indicating that the PVA/KPA thought the 82nd was in Japan. Nothing came of either proposal.[3]: 313

A continuing interdiction campaign opened by the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) in January and about to be joined by the carriers and gunnery ships of Task Force 77 offered possible help in blunting PVA/KPA offensive preparations. In laying out this campaign FEAF commander General George E. Stratemeyer had emphasized attacks on the rail net since its capacity for troop and supply movements was much greater than that of the roads; he had stressed in particular the destruction of railroad bridges. To date, results had been less than originally hoped for, because of both an overestimate of FEAF capabilities and an underestimate of PVA/KPA countermeasures. But as the attacks continued, a principal point in the selection of targets remained that dropping the railroad bridges and keeping them unserviceable would leave the PVA/KPA with no usable stretch of rail line more than 30 miles (48 km) long.

On 5 March Ridgway had his five-day forward supply levels in all items except petroleum products. Severely taxed railroad facilities would need two more days to complete petroleum shipments. In the meantime, intelligence operations provided no confirming clues that a PVA/KPA offensive was an immediate threat. In evaluating the PVA/KPA's most likely course of action Tarkenton predicted that they would defend the line he had described at the first of the month, but with changes in the frontline order of battle. The PVA 39th and 40th Armies appeared to have withdrawn from the front. This withdrawal left the KPA I Corps and PVA 50th Army in the western sector of the line, the 38th, 42nd and 66th Armies in the central area, and the KPA V, III and II Corps and 69th Brigade in the remaining ground to the east. With supply requirements all but met, IX and X Corps finishing their advance to the Arizona Line, and no clear indication of an imminent enemy offensive at hand, Ridgway on 5 March ordered Operation Ripper to begin on the morning of 7 March.[3]: 314

Objectives

editThe final objective line of the operation, the Idaho Line, was anchored in the west on the Han River 8 miles (13 km) east of Seoul. From that point it looped steeply northeastward through the eastern third of the I Corps' zone and almost to the 38th Parallel in the IX Corps’ central zone, then fell off gently southeastward across the X Corps and ROK zones to Hap’yong-dong, an east coast town 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Gangneung. Since Line Idaho traced a deep salient into PVA/KPA territory, a successful advance to it would carry the Eighth Army, in particular IX Corps in the center, into an area believed to hold a large concentration of PVA/KPA forces and supplies. Prize terrain objectives in the central zone were the towns of Hongcheon and Chuncheon. Both were road hubs, and Chuncheon, nearer the 38th Parallel, appeared to be an important PVA/KPA supply center. In the major Ripper effort, IX Corps, now commanded by Major General William M. Hoge, was to seize the two towns as it moved some 30 miles (48 km) north to the deepest point of the Idaho salient. The 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team (187th RCT), currently undergoing refresher training at Daegu, was to assist IX Corps attack should an opportunity arise to employ airborne tactics profitably.[3]: 315

To Hoge's right, X Corps was to move to a segment of the Idaho Line whose most northerly point lay about 20 miles (32 km) above the present Corps' front. In clearing PVA/KPA forces from this territory, Almond was to pay particular attention to the two principal north-south corridors in his zone, one traced by the Soksa-ri-Pangnim-ni segment of Route 20 at the Corps' right, the other by a lesser road running south out of P’ungam-ni in the left third of the Corps' zone. Responsibility for the remaining ground to the east was once again divided between ROK III and ROK I Corps. Believing that the ROK sector needed to be strengthened, particularly after the Capital Division lost almost 1,000 men in the ambush at Soksa-ri on 3 March, Ridgway had detached the ROK I Corps headquarters and the ROK 3rd Infantry Division from X Corps, sending the division to rejoin ROK III Corps and reestablishing ROK I Corps with the ROK 9th and Capital Divisions in the coastal zone. The ROK 5th Infantry Division, having reorganized after being hurt in the mid-February offensive, meanwhile rejoined X Corps. During the Ripper advance the two ROK Corps were to secure Route 20. In the coastal area, ROK I Corps forces already were well above this lateral road-in fact, were already on or above the Idaho Line. Inland, ROK III Corps would have to move about 10 miles (16 km) north through the higher Taebaek ridges to get onto the Idaho Line some 5 miles (8.0 km) above Route 20.[3]: 315–7

In the I Corps' zone at the west end of the army front, General Frank W. Milburn was to retain two divisions, the ROK 1st and US 3rd, in his western and central positions along the lower bank of the Han to secure the army flank and protect Inchon, where 500 to 600 tons of supplies were being unloaded daily thanks to Task Force 90 and the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade. East of Seoul on the Corps' right, the US 25th Infantry Division, now commanded by Brigadier general Joseph S. Bradley, was to attack across the Han on both sides of its confluence with the southward flowing Pukhan River. Above the Han, Bradley's division was to clear the high ground bordering the Pukhan to protect the left flank of IX Corps and to threaten envelopment of PVA/KPA forces defending Seoul.[3]: 317

Battle

editAdvance to the Albany Line

editThe opening phase of Operation Ripper gave promise that the Eighth Army might reach its final ground objectives almost by default. Employing only a delaying action by small forces, the PVA/KPA line units frequently offered stubborn resistance, including local counterattacks, but more frequently opposed approaching Eighth Army forces at long range, then withdrew. In the I Corps' zone, the 25th Infantry Division made a model crossing of the Han River before daylight on 7 March. Attacking with three regiments abreast following heavy preparatory fires on the northern bank of the river and in company with simulated crossings by other Corps' forces, the division reached the northern shore almost unopposed. Joined quickly by tanks that forded or were ferried across the river, and helped by good close air support after daybreak, the assault battalions pushed through moderate resistance, much of it in the form of small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire and a profusion of well placed antitank and antipersonnel mines, for first-day gains of 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 km).[3]: 321

Averaging similar daily gains against opposition that faded after 10 March, Bradley's three regiments reached the Albany Line between the 11th and 13th. The 35th Infantry Regiment, first to reach the phase line, cleared a narrow zone on the east side of the Pukhan River. On the west side the 24th and 27th Infantry Regiments occupied heights in the Yebong Mountain mass within 2–3 miles (3.2–4.8 km) of the Seoul-Chuncheon road and on line with the northern outskirts of Seoul to the west.[3]: 321

In the main attack, IX Corps advanced four divisions abreast. In a wide zone at the Corps' left the 24th Division attacked through the Yongmun Mountain mass, while in narrower zones in the eastern half of the corps area the US 1st Cavalry, ROK 6th and US 1st Marine Divisions moved toward Hongcheon. Advancing steadily against light to moderate resistance, all but the ROK 6th Infantry Division, which the cavalrymen and Marines on either side gradually pinched out, were on the Albany Line by dark on 12 March. Accompanying forces of the 1st Marine Division attacking astride Route 29 above Hoengsong was a recovery team from the 2nd Infantry Division detailed to search for the bodies of men and the equipment lost in that area by division forces who had been supporting the X Corps’ Operation Roundup when the PVA attacked in mid-February. By 12 March the team recovered more than 250 bodies, mostly of men who had been members of Support Force 21, and retrieved the five 155-mm. howitzers left behind when the support force withdrew. (The air strikes the support force commander had requested on the abandoned weapons either had not been flown or had not found their targets.) The team also retrieved the six M5 tractors left behind by the support force artillery, evacuated four of the six tanks that had been lost, and recovered a number of damaged trucks that were of value at least for spare parts.[3]: 321–2

In the X Corps' zone, the 2nd, ROK 5th, and 7th Divisions advanced abreast, the 2nd moving through the P’ungam-ni corridor on the left, the 7th along Route 20 on the right, and the ROK 5th over the ridges in the center. In a well-fought delaying action, KPA forces kept gains short until 11 March, when they began to withdraw above the Albany Line. Against the diminishing resistance, the 2nd and 7th Divisions each placed a regiment on the phase line on 13 March. At Corps' center, the ROK 5th Division reached the line on the following day. Immediately east, ROK III Corps reached and at some points passed above Route 20 by dark on 13 March. With forces already well above the Idaho Line in the coastal zone, ROK I Corps meanwhile made only minor adjustments to consolidate its forward positions. As of the 13th, a regiment of the ROK 9th Division and two regiments of the Capital Division occupied a line reaching northeastward from the Hwangbyong Mountain area to the coast near the town of Chumunjin. A problem meanwhile had arisen in rear of ROK I Corps when the KPA 10th Division, isolated behind Eighth Army lines since January, opened a bid to return to its own lines. Though much reduced by efforts of the 1st Marine Division until mid-February and the ROK 2nd Division thereafter to destroy the unit in the Pohang-Andong-Yongdok area, the division had maintained a formal organization of a headquarters and three regiments and with a surviving strength of about 2,000 had managed by the opening of Operation Ripper to slip north through the Taebaek Mountains to the Irwol Mountain region, 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Andong. Easily withstanding further efforts of the ROK 2nd Division to eliminate it, the division by 13 March reached the Chungbong Mountain area, about 25 miles (40 km) miles south of Gangneung. As the KPA unit approached the ROK I Corps' rear, General Kim sent two regiments of the ROK 9th Division and a battalion of the Capital Division south to intercept it. The two forces clashed briefly in the Chungbong heights on the morning of the 13th to open what would become a cat-and-mouse affair lasting ten days.[3]: 322

Advance to the Buffalo Line

editDuring the evening of the 13th Ridgway ordered the next phase of the advance to begin the following morning. In the west, the 25th Infantry Division was to advance toward a segment of the Buffalo Line bulging 4 miles (6.4 km) above the Seoul-Chunchron road in a zone confined to the west side of the Pukhan River. In the main attack, IX Corps was to make its major effort in the right half of the Corps' zone, sending the 1st Cavalry and 1st Marine Divisions to clear Hongcheon and then to occupy the Buffalo Line above town to block Route 29 leading northwest to Chuncheon and Route 24 running through the Hongcheon River valley to the northeast. Only short advances were required in the western half of the IX Corps' zone, by the 24th Division at the left in conjunction with the I Corps advance and by the ROK 6th Division at the right to protect the flank of the forces attacking Hongcheon. To the east, X Corps and ROK III Corps were to continue toward the Idaho Line while, on the flank, ROK I Corps had only to maintain its forward positions in the coastal slopes while other Corps' forces concentrated on eliminating the KPA 10th Division.[3]: 322–3

Against the continued advance, according to estimates prepared by Eighth Army intelligence as the initial assault concluded, the PVA delaying forces backing away from the 25th Infantry Division and the four divisions of IX Corps were expected to join their parent units in defenses in the next good system of high ground to the north located generally on an east-west line through Hongcheon. Presenting something of a barrier to this ground in the IX Corps' zone was the Hongcheon River, which flowed into the zone from the northeast to a bend below Hongcheon town, then meandered west to empty into the Pukhan. Tarkenton expected the KPA forces in the higher ridges to the east to withdraw to positions on line with those of the PVA in the IX Corps' zone, but did not expect the KPA defending Seoul and the ground west of the city, all of whom were outside the zone of the Ripper advance, to abandon their positions along the Han. Tarkenton also believed that PVA/KPA forces were now prepared, or nearly so, to make some form of strong counter effort and that they well might open it out of the Hongcheon area when Ridgway's forces arrived in that region. But on this count, as well as in his estimate of enemy defensive plans, the continuation of Operation Ripper would prove Tarkenton in error. The evidence of a PVA/KPA buildup collected by the army intelligence staff was nonetheless valid. At the same time, it was incomplete and off the mark in the identification and location of units.[3]: 323

KPA and PVA buildup

editWhat the intelligence staff had reported in mid-February as the entry of seven new PVA armies into Korea was largely the return of the three KPA corps and nine divisions that had withdrawn into Manchuria for reorganization and retraining the past autumn. Beginning in January, KPA VI Corps, with the 18th, 19th and 36th Divisions, crossed the Yalu River at Ch’ongsongjin, 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Sinuiju. Avoiding Route 1 in favor of lesser roads nearby, Corps' commander Lieurenant general Choe Yong Jin took his divisions south into Hwanghae Province and assembled them in the Namch’onjom-Yonan area northwest of Seoul. On arriving there in mid-February, Choe assumed command of the KPA 23rd Brigade previously stationed in the area to defend the Haeju sector of the Yellow Sea coast.[3]: 323

Eighth Army intelligence identified and caught the southward movement of KPA VI Corps by 1 March but remained in the dark, even at midmonth, about the reentry of KPA VII and VIII Corps. Crossing the Yalu at Sinuiju in January, VII Corps, with the 13th, 32nd and 37th Divisions, proceeded across Korea in a drawn out series of independent movements by subordinate units to the Wonsan area, closing there by the end of February. In the same time VIII Corps, with the 42nd, 45th and 46th Divisions, reentered Korea at Manp’ojin and, without the 45th Division, moved across the peninsula to the Hungnam area. The 45th Division proceeded to Inje, just above the 38th Parallel in eastern Korea, to join KPA III Corps as a replacement for the 3rd Division, which the III Corps had left in the Wonsan area when it moved to the front. Once in Wonsan, VII Corps commander Lt. Gen. Lee Yong Ho assumed command of the 3rd Division and also the 24th Division, which was defending the coast in that area. Similarly, on arriving in Hungnam with two divisions, Lt. Gen. Kim Chang Dok, commander of VIII Corps, accumulated two other units already in the vicinity, the 41st Division and 63rd Brigade. Thus, by the beginning of March KPA reserves in the Hungnam-Wonsan area totaled two corps with eight divisions and a brigade. As late as the middle of the month Ridgway's intelligence staff was aware only of the two divisions and brigade that had been in the region for some time. Besides the recently arrived VI Corps, KPA reserves in western North Korea included the IV Corps, whose location and composition Eighth Army intelligence at mid-March had yet to discover. Operating in northeastern Korea until late December, the headquarters of the IV Corps had then moved west to the Pyongyang area. Since that time, under the command of Lieutenant general Pak Chong Kok and operating with the 4th, 5th and 105th Tank Divisions and the 26th Brigade, the IV Corps had had the mission of defending the Yellow Sea coast between Chinnamp’o and Sinanju.[3]: 324

With the return of forces from Manchuria, KPA reserves by early March altogether numbered four corps, 14 divisions, and three brigades. These and the units at the front, including the 10th Division currently attempting to return to its own lines, gave the KPA an organization of eight corps, 27 divisions, and four brigades. This force was not nearly so strong as its numerous units would indicate. Most divisions were understrength, and many of those recently reconstituted were scarcely battle worthy. Before March was out, in fact, two divisions, the 41st and 42nd, would be broken up to provide replacements for others. Nevertheless, the KPA had recovered measurably from its depleted condition in early autumn of 1950. There was also fresh leadership in to KPA high command. In a recent change, Lieutenant general Nam Il replaced General Lee as chief of staff. Nam, about forty years old, had a background of college and military training in the Soviet Union and World War II service as a company grade officer in the Soviet Army. A close associate of Premier Kim Il Sung, Nam had a solid political, if not military, foundation for his new post. Nam's headquarters was in Pyongyang, where in December Lee had reassembled the General Headquarters staff from Manchuria and Kanggye. Front Headquarters, the tactical echelon of General Headquarters, was again in operation (apparently in the town of Kumhwa, located in central Korea some 30 miles (48 km) north of Chuncheon). General Kim Chaek, the original commander of this forward headquarters, had died in February. Now in command was Lieutenant general Kim Ung, who during World War II had served with the Chinese 8th Route Army in north China and more recently had led the KPA I Corps in the main attack during the initial invasion of South Korea. A solid tactician, he was currently the ablest KPA field commander. The PVA forces in Korea also were under new leadership, in either January or February Peng Dehuai had replaced Lin Piao as commander of the PVA. In company with the change in command, a surge of fresh Chinese units from Manchuria had begun. During the last two weeks of February the XIX Army Group, with the 63rd, 64th and 65th Armies, crossed into Korea at Sinuiju, and during the first half of March the group commander, Yang Teh-chih, assembled his forces not far above the 38th Parallel northwest of Seoul in the Kumch’on-Kuhwa-ri area between the Yesong and Imjin rivers. Also entering in late February were the 9th Independent Artillery Regiment and the 11th Artillery Regiment of the 7th Motorized Artillery Division.[3]: 324–5

As these forces entered, the IX Army Group, which had been seriously hurt in the Battle of Chosin Reservoir and which now had been out of action for two months, was well along in refurbishing its three armies, the 20th, 26th and 27th. At the time of this group's entry into Korea, each of its armies had been reinforced by a fourth division. The extra divisions had been inactivated, and their troops were being distributed as replacements among the remaining units. By 1 March the 26th Army had begun to move into an area near the 38th Parallel behind the central sector of the front. The Eighth Army intelligence staff quickly picked up the move of the 26th, but even at mid-March the staff had only a few reports-which it did not accept-that any part of the XIX Army Group had entered Korea.[3]: 325–6

As part of the buildup, four armies of the XIII Army Group, all in need of restoration, were replaced at the front during the first half of March. By the l0th, the 26th Army moved southwest out of its central reserve location to relieve the 38th, and 50th Armies, which had been opposing the 25th Division and 24th Division. Upon relief, the 38th withdrew to the Sukch’on area, north of Pyongyang, where it came under the control of Headquarters, PVA. The 50th returned to Manchuria, reaching Antung by the end of the month. The 39th and 40th Armies, which had left the line before the start of the operation and had assembled in the Hongcheon area, meanwhile began relieving the 42nd and 66th Armies in the central sector, completing relief on or about 14 March. On being replaced, the 42nd moved north to Yangdok, midway between Pyongyang and Wonsan, for reorganization and resupply. Like the 38th, the 42nd also passed to Headquarters, PVA control. The 66th had seen its last day of battle in Korea. En route to Hebei Province, its home base in China, the army paraded through Antung, Manchuria, on 2 April. As these frontline changes were made, another complement of fresh Chinese forces began entering Korea. First to enter in March was the independent 47th Army, commanded by Zhang Tianyun. The army was assigned to the XIII Army Group but not given a combat mission. Its divisions, the 139th, 140th and 141st, were sent to the area above Pyongyang to construct airfields at Sunan, Sunch’on and Namyang-ni, respectively. Coming into Korea at the same time was the 5th Artillery Division, which because of its means of transportation was known also as the "Mule Division." This unit, too, was assigned to the XIII Army Group. Following these units into Korea was a far larger force, the III Army Group, with the 12th, 15th and 60th Armies. At mid-March this group was still in the process of entering the peninsula and assembling in the Koksan-Sin’ggye-Ich’on region north of the area occupied by the newly arrived XIX Army Group. The final force due to enter Korea in March made up the bulk of the 2nd Motorized Artillery Division. Entering late in the month, the division would join its 29th Regiment already in Korea. When all Chinese movements in March were completed, the strength of the PVA would have risen to four army groups with 14 armies and 42 divisions, these supported by four artillery divisions and two separate artillery regiments. As sensed by Eighth Army intelligence, the buildup was in preparation for an offensive. But the offensive would not originate in the Hongcheon area, as Tarkenton thought possible, nor was it imminent. The movement and positioning of reinforcements from Manchuria would continue through most of March; the remainder of the IX Army Group would not be fully ready to move south until the turn of the month; and the refurbishing of other units, both North Korean and Chinese, would require even more time. In line with the doctrine of elastic, or mobile, defense, small forces meanwhile would continue to employ delaying tactics against the Ripper advance. With some exceptions, the delaying forces would give ground even more easily than they had during the opening phase of the operation as they fell back toward the concentrations of major units above the 38th Parallel.[3]: 326–7

Capture of Hongcheon

editIn ordering the second phase of Ripper to begin, Ridgway allowed for the possibility that the PVA would set up stout defenses in the ground immediately below Hongcheon and instructed the IX Corps' commander to take the town by double envelopment, not by frontal assault. Accordingly, Hoge directed the 1st Cavalry Division to envelope it on the west and the 1st Marine Division to move around it on the east. Hongcheon actually lay in the Marine zone near the boundary between the two divisions. As Hoge's forces attacked north on the morning of the 14th, it became steadily clearer that they would meet little resistance in the ground below their objectives. Long range small-arms fire and small, scattered groups of PVA who made no genuine attempt to delay the advance toward Hongcheon were the extent of the opposition the 1st Cavalry and 1st Marine Divisions encountered during the morning. The 24th Division and the ROK 6th Division, which had rejoined the advance in a new zone on the right of the 24th, met no resistance at all in making their short advances in the western half of the Corps' zone.[3]: 327–8

Prompted by the easy morning gains, Hoge recommended to Ridgway that the 24th and ROK 6th Divisions extend their advances to the lower bank of the Hongcheon River and to the Chongpyong Reservoir, located within a double bend of the Pukhan just west of the mouth of the Hongcheon. Ridgway approved, and through the afternoon the two divisions continued to advance, still unopposed, within 2–4 miles (3.2–6.4 km) of the river line. In continuing the attack on Hongcheon, the 1st Cavalry Division advanced against scant resistance and reached the Hongcheon River west of town late in the afternoon. The 1st Marine Division, moving more slowly in descending the Oum Mountain mass on the eastern approach, advanced to within 3 miles (4.8 km) of Hongcheon before organizing perimeters for the night. On 15 March the 24th Division at the far left of the Corps' advance moved without opposition to the lower bank of the Chongpyong Reservoir while the ROK 6th Division in the zone between the 24th and 1st Cavalry Divisions also advanced against no resistance to high ground overlooking the Hongcheon River. The 25th Division at the right of the I Corps' zone moved just as easily through the ground west of the Pukhan. By dark on the 15th the 24th Infantry and 27th Infantry reached the Seoul-Chuncheon road at the left and center of the division zone while the attached Turkish Brigade, having taken over a zone bordering the Pukhan at the far right, moved about 2 miles (3.2 km) above the road adjacent to the newly-won positions of the 24th Division. In the Hongcheon area, the 1st Cavalry Division stood fast along the Hongcheon River on the 15th to wait for the Marines to come up on its right. Strong PVA positions on a ridge due east of Hongcheon stalled the Marines in that area, but at the far left of the Marine zone the town itself fell to the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, at noon. A motorized patrol, first to enter, found the town ruined and undefended. On the return trip, following an explosion that damaged a truck, the patrol discovered that FEAF bombers had liberally sprinkled the eastern half of the town with small bombs set to explode when disturbed. A company of Marine engineers began the uncomfortable task of clearing these explosives while the 1st Battalion passed through and occupied high ground immediately northeast of the town.[3]: 328

Capture of Seoul

editBy the time Hongcheon fell, Ridgway discerned that the PVA/KPA high command had decided to abandon Seoul. The first sign appeared on 12 March when aerial observers flying over the PVA/KPA's Han River positions between Seoul and the 25th Division's bridgehead saw a large number of troops moving northwest out of that area. Patrols from the 3rd Division, which held positions along the Han opposite, crossed the river on the night of the 12th and found shoreline positions vacant. On the following night 3rd Division patrols moved more than 0.5 miles (0.80 km) above the Han without making contact. Patrols from both the 3rd Division and ROK 1st Division crossed the Han during the afternoon of 14 March. One from the 3rd Division discovered that PVA/KPA forces had vacated an important defensive position on Hill 348, the peak of a prominent north-south ridge 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Seoul. Nearer the city, another patrol moved as far north as the Seoul-Chuncheon road without contact; a third found that Hill 175, one of the lower peaks of South Mountain hugging Seoul at its southeast edge, also was vacant. Five patrols from the ROK 1st Division entered Seoul itself. One moved all the way through the western portion of the city to the gate on Route 1 while another reached the Capitol Building near the city center and raised the South Korean flag from the dome. None of the patrols received fire or sighted PVA/KPA troops.[3]: 328–9

In continuing to search the city on the 15th, the ROK discovered only a few KPA deserters who had been away from their units too long to provide information of value. Outside Seoul, a patrol from the Belgian Battalion, recently attached to the 3rd Division, checked the ground along the eastern edge of the city without making contact; two companies of ROK troops moved unopposed through the ground just west of the city; and still farther west, an ROK patrol crossed the Han and moved more than 5 miles (8.0 km) north before running into PVA/KPA fire. Aerial observers saw no PVA/KPA activity immediately above the northern limits of Seoul but observed extensive defensive preparations and troops disposed in depth east and west of Route 3 beginning at a point 5 miles (8.0 km) to the north, roughly halfway between Seoul and Uijongbu. Assured that the KPA had withdrawn from Seoul and adjacent ground, Ridgway late on the 15th instructed Milburn to occupy the nearest commanding ground above Seoul. The general line to be occupied, which Milburn later designated Lincoln, arched across heights 2 miles (3.2 km) to the west and north of Seoul, then angled northeast across the ridge holding Hill 348 to join the Buffalo Line in the 25th Division's zone. Ridgway left it to Milburn to decide the strength of the forces who would cross the river, but restricted their forward movement, once they were on the Lincoln Line, to patrolling to the north and northwest to regain contact. The restriction on further advances applied to the 25th Division as well. The principal objective at the moment, Ridgway explained to Milburn, was not to attack the enemy but simply to follow his withdrawal.[3]: 329–30

Assigning the segment of the Lincoln Line encompassing Seoul to the ROK 1st Division and the shorter portion east of the city to the 3rd Division, Milburn instructed General Paik Sun-yup to occupy his sector with a regiment, General Robert H. Soule to hold his with a battalion reinforced by not more than two platoons of tanks. Paik was to send combat patrols in search of PVA/KPA forces to the northwest while Soule sent armored combat patrols to regain contact to the north. Meanwhile, as bridges were put across the river, one in each division zone, Paik could place a second regiment on the Lincoln Line and Soule could increase his bridgehead force to a full regiment. As expected, there was no opposition when the two division commanders sent forces across the Han on the morning of the 16th. By early afternoon the ROK 15th Regiment moved through Seoul into position on the far side of the city, and the 2nd Battalion, 65th Infantry Regiment occupied the Hill 348 area. Seoul, as it changed hands for the fourth time, was a shambles. Bombing, shelling, and fires since the Eighth Army had withdrawn in January had taken a large toll of buildings and had heavily damaged transport, communications, and utilities systems. Two months of work would be required to produce even a minimum supply of power and water, and local food supplies were insufficient even for the estimated remaining two hundred thousand of the city's original population of 1.5 million. Soon after Seoul was reoccupied, therefore, a concerted, but not entirely successful effort, began via the press, radio, and police lines to prevent former residents from returning to the city while it was made livable again and while local government was restored under the guidance of civil assistance teams and ROK officials. Pusan meanwhile remained the temporary seat of national government.[3]: 330

This time there was no ceremony dramatizing the reoccupation of Seoul as there had been at the climax of the Inchon landing operation the past September. MacArthur visited Korea on 17 March but elected not to enter Seoul and limited his inspection to the 1st Marine Division as IX Corps prepared to move forward toward Chuncheon.[3]: 330

Capture of Chuncheon

editOn the morning of 16 March the Marines held up the day before by strong PVA/KPA positions east of Hongcheon discovered that the occupants had withdrawn during the night. They encountered only light resistance as they continued toward the Buffalo Line north and northeast of Hongcheon. In the western half of the IX Corps' zone, patrols from the 24th Division and ROK 6th Division searching above the Chongpyong Reservoir and Hongcheon River encountered almost no opposition. Immediately west of Hongcheon, however, the 1st Cavalry Division since reaching the Hongcheon River on 14 March had run into heavy fire and numerous, if small, PVA/KPA groups while putting two battalions into position just above the river and sending patrols to investigate farther north. This resistance and aerial observation of prepared positions indicated that the PVA planned to offer a strong delaying action in the ground bordering Route 29 between Hongcheon and Chuncheon.[3]: 330–1

To assist the advance above Hongcheon, Ridgway on the 16th authorized Hoge to move all of his divisions forward. The intention was that advances by the two divisions in the western half of the Corps' zone, in particular by the ROK 6th Division in its zone adjacent to the 1st Cavalry Division, would threaten the flank of the PVA in front of the cavalrymen. Accordingly, Hoge ordered his two divisions in the west and the 1st Cavalry Division to advance 5–6 miles (8.0–9.7 km) beyond their current river positions to the Buster Line, which was almost even with the Buffalo Line objectives of the 1st Marine Division on the Corps' right. While the 24th Division completed preparations for crossing the Pukhan at the far left, Hoge's other divisions attacked toward Lines Buster and Buffalo on 17 March. Much as anticipated, the Marines on the right and the ROK on the left met negligible resistance while the 1st Cavalry Division in the center received heavy fire and several sharp counterattacks in a daylong fight for dominating heights just above the Hongcheon River. On the 18th, with all four divisions moving forward, the resistance faded out, and it became clear that the PVA were withdrawing rapidly. Advancing easily against minor rearguard action, Hoge's forces were on or near the Buster-Buffalo Line by day's end on 19 March. The highlight of the advance on the 19th occurred in the zone of the ROK 6th Division after a patrol in the van of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment, discovered a PVA battalion assembling in a small valley 3 miles (4.8 km) above the Hongcheon River. Major Lee Hong Sun, commander of the 2nd Battalion, swiftly deployed forces on three sides of the enemy unit and attacked. Lee's forces killed 231 PVA, captured two and took a large quantity of weapons without suffering a casualty.[3]: 331–2

On 18 March, as the rapid PVA withdrawal became evident, Ridgway ordered IX Corps to continue its attack and take Chuncheon. Hoge opened the move by instructing his divisions on the 19th to proceed to the next Ripper phase line, Cairo, 4–6 miles (6.4–9.7 km) above their Buster-Buffalo objectives. Once on the Cairo Line, the 1st Cavalry Division would be on the southern lip of the basin in which Chuncheon was located and within 5 miles (8.0 km) of the town itself. Ridgway meanwhile alerted the 187th RCT for operations in the Chuncheon area. The landing plan, code-named Hawk, called for the 187th with the 2nd and 4th Ranger Companies attached to drop north of the town on the morning of 22 March and block PVA/KPA movements out of the Chuncheon basin. IX Corps' forces coming from the south were to link up with the paratroopers within 24 hours. Easy progress by Hoge's divisions on 20 and 21 March and the continuing rapid withdrawal of PVA forces made it evident that the projected airborne operation would not be profitable. Ridgway canceled it on the morning of the 21st as the 1st Cavalry Division came up on the Cairo Line without opposition. Moving ahead of the main body of the division, an armored task force meanwhile entered the Chunchon basin and at 13:30 on the 21st entered the town itself. It was empty of both PVA/KPA troops and supplies. The task force made contact only after moving 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Chuncheon over Route 29 in the Soyang River valley and then located only a few troops who scattered when the force opened fire.[3]: 332

During this search to the northeast a second task force from the cavalry division reached Chuncheon in midafternoon, just in time to greet Ridgway, who, after observing operations from a light plane overhead, landed on one of the town's longer streets. As a precaution against any PVA/KPA attempt to retake the town during the night, Ridgway before leaving instructed both task forces to return to the cavalry division's Cairo Line positions by dark. The precaution was unnecessary. Chuncheon remained vacant until the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, set up a patrol base in the town on the following day.[3]: 333

The eastern front

editWith the capture of Chuncheon, all major ground objectives of Operation Ripper were in Eighth Army hands. To the east, X Corps and ROK III Corps had reached the Idaho Line by 17 March. KPA forces had offered stiff resistance to the attack on only one day, the 15th, and then only in the X Corps' area. Prisoners taken during the advance indicated that the KPA V, II, and III Corps were withdrawing above the 38th Parallel to reorganize and prepare for offensive operations. Searching to confirm this information, Ridgway on 18 March ordered all three corps on the eastern front to reconnoiter deep beyond the parallel in the area between the Hwach’on Reservoir, located almost due north of Chuncheon, and the east coast.

As Ridgway's forces in the east consolidated positions along the Idaho Line and sent patrols north, the problem of the KPA 10th Division remained. On 20 March Ridgway pressed the ROK chief of staff and the Korean Military Advisory Group chief to eliminate the enemy unit. But in the difficult Taebaek terrain, the retreating division, although it lost heavily to air and ground attacks, separated into small groups and managed to find ways northwest through the mountains. After a flurry of small engagements while infiltrating the Idaho Line fronts of ROK III Corps and ROK I Corps, the remnants of the division, less than 1,000 men, reached their own lines on 23 March. In the days following, the reduced division moved to Ch’ongju, deep in northwestern Korea, and began reorganizing under the control of the KPA IV Corps as a mechanized infantry division. Still later, while continuing to reorganize and retrain, the unit was assigned to defend a sector of the west coast. It would not again see frontline duty.[3]: 333

Aftermath

editThe inability of ROK forces to eliminate the KPA 10th Division reflected the total result of Operation Ripper to date. For although the Eighth Army had taken its principal territorial objectives, it had had far less success in destroying PVA/KPA forces and materiel. Through the period 1–15 March, which included most of the harder fighting, known enemy dead totaled 7,151; as the PVA/KPA accelerated their withdrawal after the 15th, that figure had not increased to any great extent.[3]: 334

Chuncheon, the suspected PVA/KPA supply center, had been bare when entered; although numerous caches of materiel had been captured elsewhere, these had been relatively small. In sum, the PVA/KPA high command so far had succeeded in keeping the bulk of frontline forces and supplies out of range of the Ripper advance.[3]: 334

As Chuncheon fell, one area in which there appeared to be an opportunity to destroy an enemy force of some size was in the west above I Corps. According to patrol results and intelligence sources, KPA I Corps and the PVA 26th Army occupied that area, generally along and above a line through Uijongbu. Appearing most vulnerable were the three divisions of KPA I Corps in the region west of Uijongbu with the lower stretch of the Imjin River at their backs. Any withdrawal by these forces would require primarily the use of Route 1 and its crossing over the Imjin near the town of Munsan-ni; thus, if this withdrawal route could be blocked in the vicinity of its Imjin crossing, the KPA below the river would find it extremely difficult to escape attacks from the south. With this in mind, Ridgway enlarged Operation Ripper with plans for an airborne landing at Munsan-ni by the 187th RCT in concert with overland attacks by US I Corps. He called the supplemental squeeze play Operation Courageous.[3]: 334

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Bercuson, David J. (1999). Blood on the Hills: The Canadian Army in the Korean War. University of Toronto Press. pp. 92–66. ISBN 0802009808.

- ^ Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953. Da Capo Press. p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Mossman, Billy (1988). United States Army in the Korean War: Ebb and Flow November 1950–July 1951. United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 310–311. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Bibliography

edit- Appleman, Roy Edgar (1990). Ridgway Duels For Korea. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-585-17479-2. OCLC 44956046.

- Blair, Clay (1988). The Forgotten War: America In Korea, 1950–53. New York: Time Books. ISBN 978-0-8129-1670-6. OCLC 69655036.

- Fehrenbach, T. R. (1963). This Kind Of War: A Study In Unpreparedness. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 412580.

- Schnabel, James (1972). Policy And Direction: The First Year. United States Army In The Korean War. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 186037004. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2008.