Foxy Brown is a 1974 American blaxploitation action film written and directed by Jack Hill. It stars Pam Grier as the title character who takes on a gang of drug dealers who killed her boyfriend.[3] The film was released by American International Pictures as a double feature with Truck Turner. The film uses Afrocentric references in clothing and hair. Grier starred in six blaxploitation films for American International Pictures.

| Foxy Brown | |

|---|---|

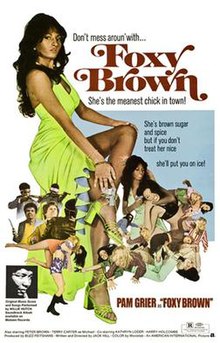

US film poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Hill |

| Written by | Jack Hill |

| Produced by | Buzz Feitshans |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Brick Marquard |

| Edited by | Chuck McClelland |

| Music by | Willie Hutch |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $500,000 |

| Box office | $2.46 million[1][2] |

While not prosecuted for obscenity, the film was seized and confiscated in the United Kingdom under section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act 1959 during the video nasty panic.[4]

Plot

editFoxy Brown seeks revenge when her government-agent boyfriend is shot down at her doorstep by members of a drug syndicate. She links her boyfriend's murderers to a "modeling agency" run by Stevie Elias and Katherine Wall that services local judges, congressmen, and police in the area. Foxy decides to pose as a prostitute to infiltrate the company, and helps save a fellow black woman from a life of drugs and sexual exploitation, and reunites her with her husband and child.

Not long after she infiltrates the company, her relationship to her late boyfriend and her brother, Lincoln 'Link' Brown, who ratted her boyfriend out, is exposed. She is caught before she can escape. After an exchange of words and heated death threats, Katherine decides to keep her alive in hopes of her being worth some money in the sex-slave trade. They give her a shot of heroin and then send her to a drug manufacturing plant with two of Miss Katherine's henchmen. After she tries to escape her captors, one of the henchmen ties her to the bed and the other gives her another shot of heroin and rapes her.

Using her quick thinking, Foxy uses a razor to get free and escapes her captors by setting the farm on fire. Katherine orders Stevie to kill Foxy; he vainly attempts to scare information out of Link, and then kills him and his girlfriend. Foxy asks her Black Panther brothers for help; they kill Stevie's partners in crime, capture Stevie, and castrate him. Foxy comes to Katherine's house and shows her the jar containing Stevie's genitals. After killing Katherine's guards and shooting her in the arm with a hidden pistol, Foxy says that death is too easy for her and wants her to suffer the way that Katherine made her suffer.

Cast

edit- Pam Grier as Foxy Brown

- Antonio Fargas as Lincoln "Link" Brown

- Peter Brown as Stevie Elias

- Kathryn Loder as Miss Katherine Wall

- Terry Carter as Dalton Ford / Michael Anderson

- Harry Holcombe as Judge Fenton

- Sid Haig as Hays

- Juanita Brown as Claudia

- Bob Minor as Oscar

- Tony Giorgio as Eddie

- Fred Lerner as Bunyon

- H.B. Haggerty as Brandi

- Boyd "Red" Morgan as Slauson

Themes and analysis

editStereotypes

editAccording to Yvonne D. Sims in her book Women of Blaxploitation, Foxy Brown was heavily criticized, not only for its "disturbing" portrayal of black womanhood, but also for its controversial stereotypes about violence and drug abuse in black culture. In a time when African Americans were making progress politically, socially, and culturally, Foxy Brown's heroine contradicted the image they were creating for themselves in society. Though Foxy is considered a heroine in this film, her role as vengeful black woman willing to pose as a prostitute and exposing herself throughout the film goes against some of the characteristics one would expect in a heroine. It also addresses the stereotype of the objectification of black women. Nelson George states that Pam Grier has been embraced by many feminists for her roles that not only display her beauty, but also her fearlessness and ability to exact retribution on men who challenge her.[5]

Blaxploitation

editBlaxploitation is a genre of exploitation films that usually targets the black audience in urban communities. Blaxploitation was very popular at the time this film was made after parts of the film industry saw untapped box-office potential in the black audience. The reputation of the blaxploitation film genre has shifted from low-budget black exploitation films to American classics worthy of deeper analysis. Although criticized for exploiting African-American culture, at the time, it provided one of the few ways for African-Americans to get into the film industry. Grier addressed this in an interview with Essence in 1979:

"Why would people think I would ever demean the Black woman? I was tried and convicted without being asked to testify in my defense. Sure, a lot of those films were junk. But they were what was being offered. They provided work for me and jobs for hundreds of Blacks. We all needed to work. We all needed to eat."[5]

Maternalism

editIn Foxy Brown and Coffy (1973), the women share a distinct characteristic; they are nurturers. In each film, the plot surrounds justice for a loved one who was a victim of drug abuse, violence, and gang activity. Foxy wants revenge for her late boyfriend, Michael, and she also wants to shut down the drug and prostitute operation so they can no longer harm her community. Director Jack Hill made an obvious reference to Angela Davis, the American activist, when she was talking to Black Caesar, and she demands they get justice for "all of the people."[6] In Coffy, Grier was seeking revenge against the drug underworld for her younger sister getting hooked on drugs, and now has to live in a rehabilitation home. In both films, the women risk their lives carrying out vigilant missions to make the streets a better place, but also, and more importantly, to avenge their family.

Women's power movement

editThis movie spoke directly to the women's power movement and struggle in the 1970s. Despite criticism, Foxy was the poster child for a new type of heroine who was subsequently appropriated by the blaxploitation genre. She redefined African-American beauty, sexuality, and womanhood, which led to the diversification of African-American actresses onscreen. Grier said:

"The 1970s was a time of freedom and women saying that they needed empowerment. There was more empowerment and self-discovery than any other decade I remember. All across the country, a lot of women were Foxy Brown and Coffy. They were independent, fighting to save their families not accepting rape or being victimized... This was going on all across the country. I just happened to do it on film. I don't think it took any great genius or great imagination. I just exemplified it, reflecting it to society."[5]

Additionally, Foxy Brown and Coffy show that women can stand up for themselves and for what they believe. The image of Foxy in an evening gown, well-equipped with a gun, is a visual representation of that idea that one does not have to be masculine to have power. "Female power," according to Grier, is "very different [from] male power, and a woman should maintain it always."[5]

Production

editAccording to director Jack Hill, due to tension between American International Pictures (AIP) and him, he was not invited to direct the sequel for Coffy until last minute. Tensions arose at a screening of a different film on which AIP had been working, which they were eager to show to Hill. Hill walked out, unimpressed, and AIP made a vow to never hire him again. AIP founder Samuel Z. Arkoff reconciled with Hill, however, after the success of Coffy.[7]

Foxy Brown was originally intended to be a sequel to his Coffy, also starring Pam Grier, and originally used the working title "Burn, Coffy, Burn!"[8] However, AIP decided at the last minute it did not want to do a sequel. Therefore, it is never said exactly what kind of job Foxy Brown has – "Coffy" was a nurse, and since this was no longer to be a sequel, they could not give Foxy Brown that job and did not have time to rewrite the script to establish just what kind of job she had.

On the audio commentary on the film's DVD release, Hill mentions that he was initially against the outfits that the wardrobe department chose for Foxy Brown. Since Pam Grier had become a star in Coffy, an impetus existed to present the actress as even more stylish than she had appeared in the previous film. The 14 costumes were designed by a California couturier named Ruthie West, who was also the stylist for the Jackson 5, Thelma Houston, Bobbie Gentry, the Curtis Brothers, and Sisters Love, among others.[9] Hill, by his own account, though, initially felt that the outfits were too trendy and specific to the time period, and within a few years would cause the film to look dated and obsolete. In the years since the film's release, however, Hill has reversed his opinion on Foxy's clothes, particularly in the wake of not only Foxy Brown's ascent into pop culture icon, but also the '70s nostalgia movement that started in the mid-1990s.[7] Hill also mentioned that the character of Foxy Brown became something of a female empowerment symbol that seemed to transcend the time period of the film.

Reception

editFoxy Brown was a financial success. Produced on a budget of $500,000, it grossed $2,460,000.[1]

A. H. Weiler of The New York Times wrote that Grier was "in a rut" and "fast becoming a bore despite all the sex, brawls and gore in 'Foxy Brown'".[10] Variety wrote that even by blaxploitation standards, the film is "something of a mess. Hill's screenplay has peculiar narrative gaps that are not concealed by heaps on 'right on, brother' dialog, while his direction is frenzied without being exciting." The review concluded that Grier was "reasonably competent and self-assured" and would be interesting to see in a different role.[11] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film one star out of four and wrote, "Some critics have found meaning in recent black films featuring large, well-endowed women as heroic figures. I find nothing ground-breaking about that. 'Foxy Brown' is selling Pam Grier's body just like it was sold a couple years ago in a half-dozen Philippine women-in-prison pictures."[12] Linda Gross of the Los Angeles Times stated, "For the most part, 'Foxy Brown' is just another movie about vengeance, vigilantes, dope, call girls and violence — interspersed with sex, vulgarity and hatred."[13] The Atlanta Daily World wrote that Grier had the star caliber to "carry a film and to have the title role."[14] Verina Glaessner of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "For all its additional heavyweight violence ... Foxy Brown is in every way a far less interesting work than writer-director Jack Hill's previous film with Pam Grier, Coffy. ... Hill's colourless script does little for an actress who unmistakably has, regardless of her material, all the strength and resilience of a Jane Russell."[15]

The film holds a 61% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 23 reviews.[16]

In 2003, the character Foxy Brown was one of 400 characters nominated in AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains list.[17]

Soundtrack

editThe film's songs were written and performed by Willie Hutch, and a soundtrack album was released on Motown Records in 1974.[18]

Home media

editIn 2001, Foxy Brown was released on DVD with a commentary track by director Jack Hill.[19] In 2010, the film was digitized in High Definition (1080i) and broadcast on MGM HD. In 2013, Arrow Video released a region B/2 (UK only) restored Blu-ray that featured extras including a director's audio commentary track, new interviews with the cast, and a collector's booklet featuring new writing on the film by Josiah Howard, author of Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide.[20] In 2015, Olive Films released a region A/1 (US only) Blu-ray with no special features.[21][22]

Influence

editFoxy Brown is considered to be one of the most influential blaxploitation films,[23] with Pam Grier's character seen as the female archetype of the genre.[24][25] The film and the character of Foxy Brown have directly influenced or were referenced in multiple films in subsequent years, including Girl 6 (1996), Urban Legend (1998), Undercover Brother (2002), and Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002).[24] Jackie Brown, the Quentin Tarantino film starring Grier in the title role, is an homage to Foxy Brown.[26] In the 2001 horror film Bones, Grier references her Foxy Brown character.[27]

It is often noted by film historians as one of the first blaxploitation films to provide a portrayal of a strong and independent woman; until Grier, women often existed exclusively to support their men for a small part of the film.[6]

Additionally, Foxy Brown and the preceding film Coffy are unique for their establishment of pushers and pimps as villains.[28] Before these films, the blaxploitation genre often espoused empathy for the social positions of such individuals.

Pam Grier titled her memoir Foxy: My Life in Three Acts (2010), influenced by this film.[29]

Television series

editIn December 2016, a television series based on the film was reported as being developed by streaming service Hulu, with DeVon Franklin and Tony Krantz executive producing, and Meagan Good starring as Foxy Brown.[30] As of October 2022, the TV series has yet to appear.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Samuel Z Arkoff & Richard Turbo, Flying Through Hollywood By the Seat of My Pants, Birch Lane Press, 1992 p 202

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 300. ISBN 9780835717762. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- ^ "Pam Grier looks back on blaxploitation: 'At the time some people were horrified'". The Los Angeles Times. June 4, 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "Video Nasties Seizures". melonfarmers.co.uk. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Sims 2006, p. 76.

- ^ a b Sims 2006, p. 237.

- ^ a b Walker, David; Rausch, Andrew; Watson, Chris (2009). Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-8108-6706-2.

- ^ "Classic Corner: Foxy Brown". Crooked Marquee. March 4, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Peters, Ida (October 6, 1973). "Designer for "Foxy Brown"". The Baltimore Afro-American.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (April 6, 1974). "Pam Grier Typed as 'Foxy Brown'". The New York Times. 16.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Foxy Brown". Variety. April 17, 1974. 16.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (April 17, 1974). "The Super Cops". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 8.

- ^ Gross, Linda (April 15, 1974). "Pam on Way Up in 'Foxy'". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 19.

- ^ "Pam Grier, New Star". Atlanta Daily World. April 7, 1974.

- ^ Glaessner, Verina (March 1975). "Foxy Brown". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 42 (494): 56.

- ^ "Foxy Brown", Rotten Tomatoes, retrieved 2024-09-24

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ "Foxy Brown [Original Soundtrack]". AllMusic. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Foxy Brown". DVD Talk. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ^ Deighan, Samm (July 14, 2013). "Foxy Brown (UK Blu-Ray Review)". Diabolique Magazine. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Foxy Brown Blu-ray Review". High Def Digest. June 9, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "Foxy Brown (Blu-ray Review)". Why So Blu?. May 25, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Best Blaxploitation Movies of All Time". Complex. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ a b Kim, Kristen Yoonsoo (January 18, 2018). "The Revolutionary Power of Pam Grier's 'Foxy Brown'". Vice. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Braxton, Greg (August 27, 1995). "MOVIES : She's Back and Badder Than Ever : Pam Grier's '70s blaxploitation films are a big kick again, making the star a hot retro hero. (And you thought Foxy Brown was finished.)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "12 Fascinating Facts About Jackie Brown". Mental Floss. 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ Davis, Sandi (October 26, 2001). "Actress Grier makes no 'Bones' about film". The Oklahoman. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Coffy". Blerds Online. February 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Felicia R. (2010-05-04). "Pam Grier's Collection of Lessons Learned". The New York Times.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (13 December 2016). "'Foxy Brown' TV Series Reboot Starring Meagan Good In the Works At Hulu From DeVon Franklin, Tony Krantz & MGM TV". Deadline. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

Sources

edit- Sims, Yvonne (2006). Women of Blaxploitation: How the Black Action Film Heroine Changed American Popular Culture. North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2744-4.