Francis Aidan Cardinal Gasquet OSB (born Francis Neil Gasquet;[1] 5 October 1846 – 5 April 1929) was an English Benedictine monk and historical scholar.[2] He was created Cardinal in 1914.

Francis Aidan Gasquet | |

|---|---|

| Vatican Librarian and Archivist of the Holy Roman Church | |

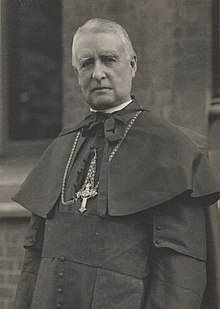

Photograph by Walter Stoneman, c. 1916 | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 19 December 1874 |

| Created cardinal | Cardinal deacon 25 May 1914; elevated to Cardinal priest 18 December 1924 by Pope Pius X (cardinal deacon), Pope Pius XI (cardinal priest) |

| Rank | Cardinal deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro (1914–1915); Cardinal deacon, later Cardinal priest, of Santa Maria in Portico (1915–1929) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francis Neil Gasquet 5 October 1846 Somers Town, London, England |

| Died | 5 April 1929 (aged 82) Palazzo San Callisto, Rome, Italy |

| Buried | Downside Abbey, Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Somerset, England |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Education | Downside School |

Life

editGasquet was the third of six children of Raymond Gasquet, a physician whose French naval officer father had emigrated to England during the British evacuation of Toulon in 1793. His mother was a Yorkshirewoman. He was born at 26 Euston Place, Somers Town, London.[3][4][5]

Educated at Downside School, he entered the Benedictines in 1865 at Belmont Priory. He moved to Downside Abbey where he was professed and, on 19 December 1871, ordained a priest. From 1878 to 1885 he was prior of Downside Abbey, resigning because of ill health; but he retained a life long interest in the development of the monastic buildings, in particular the abbey church.[6]

Upon his recovery, he became a member of the Pontifical Commission to study the validity of the Anglican ordinations (1896) leading to Apostolicae curae, to which his historical contribution was major. In 1900, he became abbot president of the English Benedictines. He was President of the Pontifical Commission for Revision of the Vulgate, 1907. He also authored the major history of the Venerable English College at Rome.

He was created Cardinal-deacon in 1914 with the titular church of San Giorgio in Velabro. He was conferred the titular church of Santa Maria in Portico in 1915. In 1917, he was appointed Archivist of the Vatican Secret Archives. In 1924, he was appointed Librarian of the Vatican Library. He died in Rome.[citation needed]

As a historian

editGasquet's historical work, especially his later work, has been attacked by later writers. Geoffrey Elton wrote of "the falsehoods purveyed by Cardinal Gasquet and Hilaire Belloc".[7] His collaboration with Edmund Bishop has been described as "an alliance between scholarship exquisite and deplorable".[8]

A polemical campaign by anti-Catholic G. G. Coulton[9] against Gasquet was largely successful in discrediting his works in academic eyes.[10] One of his books contained an appendix "A Rough List of Misstatements and Blunders in Cardinal Gasquet's Writings.[11]

David Knowles wrote a reasoned piece of apologetics on Gasquet's history in 1956, Cardinal Gasquet as an Historian.[12] In it he speaks of Gasquet's "many errors and failings", and notes that he "was not an intellectually humble man and he showed little insight into his own limitations of knowledge and training". Knowles felt Coulton, though, was in error through over-simplifying the case.[13] In his advanced years "Gasquet’s capacity for inaccuracy amounted almost to genius".[14]

Eamon Duffy wrote that Gasquet was "a generously talented man," whose first book on Henry VIII "contained a good deal of fresh and worthwhile research and offered a spirited challenge to traditional Protestant historiography of the Reformation" had been greeted as "doing much to rescue a crucial aspect of late medieval religion from the calumny of centuries;" but whose subsequent books all had highly valuable information but offered "a highly idealized picture of Catholic England from which every shadow and blemish had been air-brushed out or explained away."[14] He said in an interview:

...Cardinal Francis Aidan Gasquet, a great Benedictine historian, was both a bad workman and not entirely scrupulous about what he said. So you can be a churchman and a lousy historian.[15]

His book on the Black Death was one of the first to draw attention to this event, now considered critical in European History.

A biography, Cardinal Gasquet: a Memoir, (Burns & Oates 1953), was written by Shane Leslie, who knew him personally.

Gasquet was a revisionist on several issues. For example, his theory that at least some of the Wycliffite Bible versions pre-date or bypass Wycliffe was immediately condemned by English historians[16] but credibly highlighted the paucity of evidence for the conventional provenance and has been partly revived in 2016 by historian Henry Ansgar Kelly;[17]: 9 it is now a conventional belief by historians that Wycliffe may not have personally translated any parts. Similarly unconventional was his positive re-evaluation of Erasmus in The Eve of the Reformation based on a fresh and non-sceptical reading of Erasmus' Spongia and letters.[18]

Works

edit- The Great Pestilence (A.D. 1348-9), Now Commonly Known as the Black Death, Simpkin Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Limited, 1893.

- The Old English Bible and Other Essays, John C. Nimmo, 1897.

- Henry VIII and the English Monasteries, John Hodges, 1888.

- Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer, John Hodges, 1890 (with Edmund Bishop).

- A little book of prayers from Old English sources Catholic Truth Society, 1900.

- The Eve of the Reformation, G. Bell & Sons, 1923 [1st Pub. 1900].

- Parish Life in Mediæval England, Methuen & Co., 1922 [1st Pub. 1905]. Also at Project Gutenberg.

- The Greater Abbeys of England, Chatto & Windus, 1908.[19] (illustrated by Warwick Goble)

- The Last Abbot of Glastonbury and Other Essays, George Bell & Sons, 1908.

- The Black Death of 1348 and 1349, George Bell & Sons, 1908.

- A History of the Venerable English College, Rome, Longmans, Green & Co., 1920.

- Monastic Life in the Middle Ages, G. Bell & Sons, 1922.

- His Holiness Pope Pius XI, Daniel O'Connor, 1922.

- The Religious Life of King Henry VI, G. Bell & Sons, 1923.

Articles

edit- "Roger Bacon and the Latin Vulgate." In: A.G. Little (ed.), Roger Bacon Essays. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1914.

Miscellany

edit- William M. Cunningham, The Unfolding of the Little Flower, with a Preface by Cardinal Gasquet. London: Kingscote Press, 1916.

- Father Stanislaus, Life of the Viscountess De Bonnault D'Houet, with an Introduction by Cardinal Gasquet. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1916.

References

edit- ^ "Francis Gasquet - Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ "Gasquet, Right Rev. Francis Aidan". Who's Who. Vol. 59. 1907. pp. 662–663.

- ^ "Gasquet, Raymond (1789 - 1856)". Plarr's Lives of the Fellows Online. Royal College of Surgeons of England. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Knowles, Dom David (1963). "Cardinal Gasquet as an Historian". The Historian and Character: And Other Essays. Cambridge University Press. p. 249. ISBN 9780521088411. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Sir Howard; Godfrey, Walter H, eds. (1952). Survey of London: King's Cross Neighbourhood - The Parish of St. Pancras Part IV (PDF). London County Council. p. 90. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Bellenger, p. 117

- ^ Elton, Geoffrey Rudolph (2002). The Practice of History. Oxford; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, p. 96.

- ^ Christopher Nugent Lawrence Brooke et al. A History of the University of Cambridge: University to 1546 (1988), p. 420.

- ^ Described by Duffy as a fanatic.

- ^ Nicholson, Ernest Wilson (2003). A Century of Theological and Religious Studies in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 172.

- ^ Coulton, G.G. (1915). "A Rough List of Misstatements and Blunders in Cardinal Gasquet's Writings." In: Medieval Studies. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.

- ^ Reprinted in David Knowles, The Historian and Character, and Other Essays. Cambridge University Press, 1963, pp. 240–263.

- ^ Knowles (1963), pp. 261–2.

- ^ a b Duffy, Eamon (1 February 2004). "A. G. Dickens and the late medieval Church". Historical Research. 77 (195): 98–110. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2004.00200.x.

- ^ "Confronting the Church's Past: An Interview with Eamon Duffy," Commonweal, Vol. 127, No. 1, January 2000.

- ^ Matthew, F. D. (1895). "The Authorship of the Wycliffite Bible". The English Historical Review. 10 (37): 91–99. ISSN 0013-8266.

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2016). The Middle English Bible: a reassessment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812248340.

- ^ Gasquet, Francis Aidan (1900). The Eve of the Reformation. Studies in the Religious Life and Thought of the English people in the Period Preceding the Rejection of the Roman jurisdiction by Henry VIII.

- ^ "Review: The Greater Abbeys of England by Abbot Gasquet". The Athenaeum. No. 4208. 20 June 1908. pp. 767–768.

Further reading

edit- Bellenger, Dom Aidan (2004). "Gasquet, Francis Neil (1846–1929)." In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Benson, Robert Hugh (1914). "Cardinal Gasquet," The Dublin Review, Vol. CLV, pp. 125–130.

- Escourt, R. (1921). "The Work of Cardinal Gasquet in the Field of Pre-Reformation History," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XLVI, No. 183, pp. 353–371.

- Grange, A. M. (1894). "Dom Gasquet as a Historian," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XIX, No. 75, pp. 449–464.

- Guilday, Peter (1922). "Francis Aidan Cardinal Gasquet," The Catholic World, Vol. CXV, pp. 210–216.

- Leslie, Shane (1953). Cardinal Gasquet, A Memoir. London: Burns, Oates.

- Knowles, David (1957). Cardinal Gasquet as an Historian. London: University of London, Athlone Press.

- Jacob, E. F., Lewis Bernstein Namier, Theodore Frank Thomas Plucknett, Hugh Hale Bellot, W. K. Hancock, David Knowles, and John Goronwy Edwards (1952). The Creighton Lectures, 1951–57. London: University of London, Athlone Press.

External links

edit- Great Letter Writers

- Catholic Hierarchy entry

- Works by Francis Aidan Gasquet at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Francis Aidan Gasquet at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Francis Aidan Gasquet at the Internet Archive

- Francis Aidan Gasquet at Library of Congress, with 50 library catalogue records