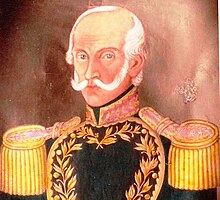

Francisco Burdett O'Connor (12 June 1791 - 5 October 1871) was an officer in the Irish Legion of Simón Bolívar's army in Venezuela. He later became Chief of Staff to Antonio José de Sucre and Minister of War of Bolivia.[1][2] Aside from Bolívar and Sucre, he is one of the few military officers of the Spanish American wars of independence to be bestowed the title of Libertador (Liberator).[3]

Francisco Burdett O'Connor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 1 November 1826 – 9 December 1827 | |

| President | Antonio José de Sucre |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | José María Pérez de Urdininea |

| Minister of War and Navy | |

| In office 3 July 1831 – 24 January 1832 | |

| President | Andrés de Santa Cruz |

| Preceded by | José Miguel de Velasco |

| Succeeded by | José Miguel de Velasco |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francis O'Connor 12 June 1791 County Cork, Ireland |

| Died | 5 October 1871 (aged 80) Tarija, Bolivia |

| Nationality | Irish, Peruvian, Bolivian |

| Spouse | Francisca Ruiloba |

| Children | Heraclia Horacio Carolina |

| Honorary title | Liberator |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1819-1839 |

| Rank | Army General |

| Battles/wars |

|

Early life and family

editFrancis Burdett O'Connor was born in Cork, Ireland, into a prominent Protestant family. His parents were Roger O'Connor and Wilhamena Bowen. His uncle Arthur O'Connor (1753-1852) was the agent in France for Robert Emmet's rebellion of the United Irishmen. His brother was the MP and Chartist leader Feargus O'Connor (1794-1855).[4] He spent much of his childhood in Dangan Castle, former childhood home of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington.[5][6]

O'Connor's father Roger was known for his eccentricities. After his wife died in 1806, he became increasingly erratic. Matters worsened in 1809 when there was a serious fire that destroyed part of the house. Francisco wrote in his autobiography 60 years later that he had accidentally started the fire himself when melting lead to create bullets.[7][5] In 1817 his father was arrested for allegedly organising a mail robbery. He was acquitted, but local rumours continued to blame him for the crime.[6] The family no longer felt welcome in the area. Francis and his brother Feargus decided to leave, stealing horses from their brother Roderic, travelling to London and asking to be taken in by family friend M.P. Francis Burdett. Burdett looked after them, and Francisco later added his name to his surname.[6]

The Spanish American wars of independence

editCampaigns in Venezuela and Colombia

editIn 1819, Francis O'Connor enlisted in the Latin American independence cause of Simon Bolivar, and sailed from Dublin with 100 officers and 101 men of the Irish Legion under the command of Colonel William Aylmer. The force arrived at Margarita Island off the coast of Venezuela in September 1819 to find that conditions were squalid and nothing was prepared.[1] After losses through death and desertion, in March 1820 the force attacked the city of Riohacha on the mainland, which they temporarily occupied. Later, the force was involved in the siege of Cartagena and the campaign against Santa Marta. However, the Irish soldiers became demoralized by the cautious and inept conduct of the war by General Mariano Montilla and indiscipline evolved into mutiny. In June 1820 the force was disarmed and shipped to Jamaica.[8] While in Huaraz, O'Connor received a letter from Simón Bolívar, calling him to partake in the United Army of Liberation.[5]

Campaigns in Peru and Bolivia

editO’Connor joined the United Army of Liberation in Peru in 1824, and, six months later, Bolívar appointed him chief of staff. He fought at the Battle of Junín in August 1824 against heavy odds, where he was nearly killed by a Spanish soldier.[5] Prior to the Battle of Ayacucho, O'Connor strategically retreated to the plains of Ayacucho, saving the patriot army from a complete encirclement by the Spanish forces. Although reluctant, Sucre agreed with O'Connor and ordered the army to set up a defensive position where the Irishman had suggested. The Spanish army attacked and were defeated by the patriots.[5]

This battle is considered the end of the Spanish-American Wars of independence. Spanish General Canterac confessed to O'Connor after the battle that the choice of position made by the patriot army was a major factor in the defeat of the royalists.[5]

Upper Peruvian Campaign

editIn 1825 Antonio José de Sucre chose him to direct the Campaign in Upper Peru, the final operation of the war, in pursuit and elimination of general Pedro Antonio Olañeta, the last royalist commander to offer resistance.[9][10] However, while he was marching south, he learned that Olañeta had been killed by his own troops at the Combat of Tumusla, suddenly ending the Campaign in Upper Peru.[5][11]

The nascent years of the Bolivian Republic (1825-1829)

editIn 1826, Francisco O'Connor was appointed military governor of Tarija. In 1827, he published a proclamation encouraging Irish people to settle in the 'New Erin' of Tarija.[11][12] Furthermore, Bolívar would send O'Connor to make a survey of the Bolivian coast and determine which location was the best for Bolivia's main port of Cobija.[11]

In 1828, O'Connor witnessed the events of that fateful year, namely the tragic ending of Pedro Blanco Soto, as he was in Sucre the night of the President's untimely assassination. Not completely certain of what had occurred that night, O'Connor finally uncovered the truth years later from one of Blanco's guards the night of his death, writing it years later in his Recuerdos. The Irishman writes the following account of the murder:

There were rumors, of course, that General Blanco had been assassinated by the orders of the captain of the National Guard and that the first Chief of First Battalion, Colonel José Ballivian. In fact, many suppose it that way until now in Chuquisaca; however, finding myself in Peru in the year 1836 with the Bolivian Army... Lieutenant Colonel Prudencio Deheza, the same one who commanded the guard corps in the Recoleta convent of Chuquisaca the night of the cruel assassination of General Blanco, told me about that tragic event as follows: The order that was posted to the guards that day was: that in case of any attempt by the cholada [the indigenous popular masses of Bolivia] to rescue the prisoner, that he not be allowed to escape with his life. This order was read to all the troops that made up the guard; and that same night, at midnight, the sentinel stationed in the corridor, sounded the alarm, and stated that groups of cholos were approaching the high wall in front of the convent. All guards armed themselves, and Deheza set up in his designated position. All this happened next to the cell in which the unfortunate General Blanco was imprisoned. With a sentinel at the door and another inside the same cell. At this time, Blanco was sleeping on a pallet in his cell, and hearing the noise in the corridor he was awaken. He was going to the door to see what was happening, when the sentinel in sight pushed him with his bayonet onto the pallet and shot him. The captain of the guard entered the cell and the sentinel told him that the prisoner had tried to escape; the gatekeeper also entered the cell, and shot Blanco a second time. Deheza then entered and finished him off with his sword.[13]

The Presidency of Santa Cruz

editO'Connor had retired to his hacienda in Tarija after the tragic end of President Blanco, where he planned to remain unless called upon by his country. The possibility of a Peruvian invasion and the souring of relations between Peru and Bolivia compelled President Andrés de Santa Cruz to recall O'Connor to active service. O'Connor accepted the President's call to arms, yet no war nor Peruvian invasion took place. Rather, after the defection of three Peruvian ships, Agustín Gamarra chose to sign a treaty with Bolivia to ensure peace.[5]

O'Connor, hopeful to return to his hacienda, was not allowed to leave La Paz by Santa Cruz, who instead promoted him to Army general. Honoured, O'Connor remained in La Paz with the President and was given the position of Minister of War and Navy after José Miguel de Velasco took leave in July 1831. Although needed in La Paz, O'Connor was dispatched by Santa Cruz to the Southern border with Argentina when the caudillo Facundo Quiroga threatened to invade and annex the Tarija Department, a region long considered to be Argentine by the citizens of that country.[5] Santa Cruz, in a letter to O'Connor, stated:

No one knows that territory [the borderlands of the Tarija Department] better than you, which could soon become the theater of a campaign. You will take an Infantry battalion and a Regiment of Cavalry, will march to Tarija, and will put the whole province in a state of defense against that gaucho [Quiroga].[14]

Quiroga's invasion never came, and Santa Cruz attempted to incorporate an uninterested O'Connor into his administration. He served on an interim basis as Minister of War yet again in the year 1833, and was made President of the Council of War, for which he participated in the infamous trial of Colonel Manrique. Santa Cruz had wanted a death sentence for the colonel, however, when O'Connor ruled to fire Manrique from the army instead, a clash between the President and the Irishman took place. O'Connor, insulted by said clash, decided to retire to the borderlands in Tarija, declaring he would never serve in his administration again.[5]

The Peru–Bolivian Confederation

editThe formation of the Confederation

editHowever, in 1835, Santa Cruz wrote a letter, calling him to arms. In 1833, General Agustín Gamarra had found himself out of favour with the National Congress, which had supported General Luis José de Orbegoso as the former's successor. Gamarra remained in rebellion, however, and headed to Bolivia to request the aid of President Santa Cruz. In 1835, General Felipe Santiago Salaverry rebelled against Orbegoso and successfully ousted him. Although Santa Cruz had actually provided support to Gamarra, in the form of men and money, and had even agreed to the creation of a Peru–Bolivian Confederation, separating Peru between the Republics of North and South Peru, the alliance collapsed.

Gamarra had defeated an army that Salaverry had sent to Cusco to retake the city. In light of this victory, Gamarra broke his agreement with Santa Cruz and aspired to seize the Presidency of Peru for himself. However, he was defeated at the Battle of Yanacocha by Colonel José Ballivián.[5] It was at this point that Santa Cruz entered into an alliance with Orbegoso, with the promise of a Confederation between Peru and Bolivia.

In 1836, O'Connor marched alongside Santa Cruz and the Bolivian Army to the city of Arequipa, where Salaverry and his army were located. When the Bolivian Army entered the city, Salaverry's army was leaving, heading toward Uchumayo. Santa Cruz decided to remain in the city instead of pursuing the enemy, and, on the other side of the river, Salaverry's army rained heavy fire onto the city for six days. On 4 February, General Ballivián led a charge which was completely defeated by Salaverry, with O'Connor's division having to cover for the defeated and retreating first division. On the morning of 7 February, O'Connor spotted Salaverry's army marching toward Huascacachi. Salaverry's intention was to cut off the Bolivian supply, preventing any possible retreat by Santa Cruz into Bolivia. Sensing an opportunity, since the enemy forces were marching in thin files and were not in a position to fight, O'Connor informed Santa Cruz who ordered an immediate attack. A charge led by General Otto Philipp Braun effectively decided the outcome of the so-called Battle of Socabaya, ending in the capture and later execution of Salaverry and several of his officers.[15]

The war against Chile

editWith the new Confederation secured, Santa Cruz made three major mistakes: the annulment of the treaty of peace and friendship with Chile; the promotion of the civilian Mariano Enrique Calvo to Division general; and marginalizing José Miguel de Velasco, who had served loyally under Santa Cruz, which led to his later defection in Tupiza in 1839. O'Connor describes these as "the major blunders which cost Santa Cruz", the first being the anger of the army at the promotion of Calvo:

Congress passed a law... which had Doctor Mariano Enrique Calvo, Prosecutor of the Supreme Court and then appointed Vice President of Bolivia, in charge of the Executive Power in the absence of General Santa Cruz, promoted to division general. The soldiers of the army were very offended by the appointment of Calvo, and they told me that they did not want to accept a peso of the money that had been granted to them by Congress, and that they did not approve and could not approve the appointment of a civilian to the rank of division general.[16]

The second major blunder which O'Connor describes is the annulment of the treaty with Chile signed under Salaverry, which had led to the declaration of war by said nation:

[As for the war with Chile], the cause was the decree passed by General Santa Cruz which annulled the treaty of peace, friendship, and trade concluded between Salaverry, the intrusive president of Peru, and the Government of Chile... and the Captain General [Santa Cruz] knew it and must have weighed on him; however, he was so proud as a result of the victory at Socabaya that he imagined himself in a position to do whatever occurred to him at will, without looking at one side or the other, and this fact, which seemed insignificant to him, was the cause of his downfall and that of all the Confederation.[17]

The third major blunder O'Connor mentions is the disrespect toward and marginalization of General Velasco, whose defection in 1839 would be the event which finally toppled Santa Cruz in Bolivia:

I received from Lima the plaque of a Great Dignitary of the Legion of Honor of Bolivia, which was worth the pension of five hundred pesos for life. This dignity was not conferred on General Velasco, who had been Vice President of Bolivia for many years, and President also after the death of General Pedro Blanco, on the last night of 1828, and Chief of Staff of the Bolivian Army during the Battle of Yanacocha. Another reckless decision by General Santa Cruz, as this was the real cause behind the defection of General Velasco in Tupiza, and his pronouncement for the Restoration in February 1839, when he learned of the defeat of the Confederation Army in Yungay.[18]

The war with Chile continued when Diego Portales was assassinated by his own men, followed by a mutiny in Oruro against Santa Cruz. Sensing an opportunity, the Chileans invaded Peru and were able to occupy the city of Arequipa. The Army of the Confederation far outnumbered that of the Chilean Army in Arequipa. However, instead of achieving a decisive and crushing victory over Chile, Santa Cruz opted for the signing of a peace treaty, known as the Treaty of Paucarpata, celebrated on 17 November 1837. O'Connor vehemently disagreed with such a treaty, telling Santa Cruz that he did not believe the Chilean government would abide by such a treaty.[19] After the treaty was signed, Santa Cruz negotiated with General Manuel Blanco Encalada the sale of all the horses in the Chilean Army in Arequipa, paying very high prices for the time.

The war against Argentina

editThe Argentine Confederation under Juan Manuel de Rosas had, like the Chileans, also declared war on Santa Cruz. O’Connor was sent hurriedly to Tarija alongside General Braun to prevent the Argentine army under Gregorio Paz from seizing the province. The Argentines intended to claim the province of Tarija, long disputed with Bolivia. Although the Bolivian high command believed the enemy was located in San Luis, the Argentines were actually advancing toward Tarija. O’Connor and Braun pursued Paz and eventually caught up to his army near the Montenegro mountain range, on the banks of the Bermejo River on 24 June 1838.

The Bolivians led an uphill charge against the Argentines, who were holding a defensive position. Although Paz's men were firing ferociously, the Bolivians under O’Connor led an impressive charge which resulted in the Argentine army abandoning their positions and fleeing to safety. Braun eventually caught up with O’Connor to discover the Argentine troops fleeing and abandoning all their belongings in the process. Thus, the Battle of Montenegro came to an end with a decisive Bolivian victory.

Previously, on 11 June, the second division of the Argentine army, led by Alejandro Heredia, was defeated at the Battle of Iruya, completely repelling the attack of the enemies. When General Heredia was suddenly assassinated, the war on the south essentially ended, with the threat of an Argentine invasion eliminated.[20][11]

The second Chilean campaign and the revolution of General Velasco

editThe Chileans were quick to resume hostilities with Santa Cruz, as the so-called treaty of Paucarpata was not ratified by the Chilean government. Landing in Peru, the Restoration Army, composed of Peruvian exiles and Chileans, was able to crush Santa Cruz in the decisive Battle of Yungay, leading to the unravelling of the Confederation. On 9 February 1839, General Velasco proclaimed himself against Santa Cruz, and in the following days the Departments of Chuquisaca, La Paz, and Cochabamba declared themselves in favour of the rebellion. Velasco would erase O'Connor from the military list of Bolivia, resulting in the banishment of the latter from political and military affairs. O'Connor retired to his estate in Tarija, never to offer his services again for any government, especially not Velasco's.[21]

Death and legacy

editHe died in Tarija on 5 October 1871 at eighty years of age.[1] His memoirs entitled Independencia Americana: Recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor were published in 1895.[22] O'Connor played a key role during the battles of Junin and Ayacucho, loyally serving Sucre and organizing with Santa Cruz what came to be among the fiercest and most well-trained armies in all of South America. This army united Peru and Bolivia and, although ephemeral, would score major victories against the armies of Chile and Argentina. He is among the few military officers during the Spanish American Wars of Independence to have received the title of Liberator.

Bibliography

editBurdett O'Connor, Francisco. (1916). "Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia."[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c James Dunkerley (2000). Warriors and scribes: essays on the history and politics of Latin America. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-754-4.

- ^ Aguirre, Nataniel (1872). El general Francisco Burdett O'Connor (in Spanish). Imp. de la Union Americana.

- ^ Dunkerley, James (2000). El tercer hombre: Francisco Burdett O'Connor y la emancipación de las Américas (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-62-32-3.

- ^ Graham Wallas (1895). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 41. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 400.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k O'Connor, Francisco Burdett (1915). Independencia americana: recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, colonel del ejército, libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia (in Spanish). Sociedad española de librería.

- ^ a b c Dunkerley, James (2000). El tercer hombre: Francisco Burdett O'Connor y la emancipación de las Américas (in Spanish). Plural editores. ISBN 978-99905-62-32-3.

- ^ Francisco Burdett O'Connor, Recuerdos (1895) (La Paz, 1972), p. 5.

- ^ Brian McGinn (November 1991). "Venezuela's Irish Legacy". Irish America Magazine (New York) Vol. VII, No. XI. pp. 34–37. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ James Dunkerley (2000). Americana: the Americas in the world around 1850 (or 'seeing the elephant' as the theme for an imaginary western. Verso. p. 461ff. ISBN 1-85984-753-6.

- ^ Byrne, James Patrick; Coleman, Philip; King, Jason Francis (2008). Ireland and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History: a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-614-5.

- ^ a b c d Fanning, Tim (25 August 2016). Paisanos: The Forgotten Irish Who Changed the Face of Latin America. Gill & Macmillan Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7171-7182-8.

- ^ Dunkerley, James (2007). Bolivia: Revolution and the Power of History in the Present : Essays. Institute for the Study of the Americas. ISBN 978-1-900039-81-9.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco Burdett (1915). Independencia americana: Recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor ... (in Spanish). González y Medina. pp. 277–278.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco Burdett (1915). Independencia americana: Recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor ... (in Spanish). González y Medina. p. 308.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. pp. 362–376.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. p. 378.

- ^ Francisco, O'Connor. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. pp. 378–379.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. p. 379.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. pp. 386–387.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. pp. 392–418.

- ^ O'Connor, Francisco. Independencia americana recuerdos de Francisco Burdett O'Connor, coronel del ejército libertador de Colombia y general de división de los del Perú y Bolivia. pp. 429–430.

- ^ Mary N. Harris. "Irish Historical Writing on Latin America, and on Irish Links with Latin America" (PDF). National University of Ireland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2009.