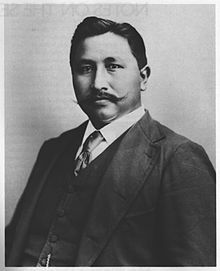

Francis La Flesche (Omaha, 1857–1932) was the first professional Native American ethnologist; he worked with the Smithsonian Institution. He specialized in Omaha and Osage cultures. Working closely as a translator and researcher with the anthropologist Alice C. Fletcher, La Flesche wrote several articles and a book on the Omaha, plus more numerous works on the Osage. He made valuable original recordings of their traditional songs and chants. Beginning in 1908, he collaborated with American composer Charles Wakefield Cadman to develop an opera, Da O Ma (1912), based on his stories of Omaha life, but it was never produced. A collection of La Flesche's stories was published posthumously in 1998.

Francis La Flesche | |

|---|---|

Francis La Flesche | |

| Born | December 25, 1857 |

| Died | September 5, 1932 (aged 74) |

| Occupation(s) | anthropologist, ethnologist, musicologist |

| Known for | First Native American anthropologist, known for his studies of Native American Omaha and Osage culture and music. Worked at Smithsonian Institution. |

| Father | Joseph LaFlesche |

| Relatives |

|

Of Omaha, Ponca, and French descent, La Flesche was the son of Omaha chief Joseph LaFlesche (also known as Iron Eye) and his second wife Ta-in-ne (Omaha). He grew up on the Omaha Reservation at a time of major transition for the tribe. Before the establishment of anthropology programs, La Flesche earned undergraduate and master's degrees at the George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C. He made his professional life among European Americans.

Early life and education

editFrancis La Flesche was born in 1857 on the Omaha Reservation, the first child of his father Joseph LaFlesche's second wife Ta-in-ne, an Omaha woman. He was half-brother to his father's first five children.[1] Their mother was Mary Gale, mixed-race daughter of an American surgeon and his Iowa wife. After Mary's death, the widower Joseph (also known as Iron Eye) had remarried. Francis attended the Presbyterian Mission School at Bellevue, Nebraska. Later he attended college and law school in Washington, D.C.

By 1853, Iron Eye was a chief of the Omaha; he helped negotiate the 1854 treaty by which the tribe sold most of their land in Nebraska. He led the tribe as a head chief soon after their removal to a reservation and in the major transition to more sedentary lives. Joseph La Flesche (Iron Eye) was Métis, of Ponca and French descent, and grew up mostly with the Omaha people. Working first as a fur trader, as an adult he was adopted as a son by the chief Big Elk. He taught him the culture and designated Iron Eye as his successor.

Joseph emphasized education for all his children; several went to schools and colleges in the East. They were encouraged to contribute to the Omaha. Francis' half-siblings became accomplished adults: Susette LaFlesche was an activist and nationally known speaker on issues of Indian rights and reform; Rosalie LaFlesche Farley was an activist and managed Omaha tribal financial affairs; and Susan La Flesche was the first Native American woman trained as a European-American style doctor; she treated the Omaha for years.

Career

editIn 1879, Judge Elmer Dundy of the US District Court made a landmark civil rights decision affirming the rights of American Indians as citizens under the Constitution. In Standing Bear v. Crook, Dundy had ruled that "an Indian is a person" under the Fourteenth Amendment. Susette "Bright Eyes" La Flesche had been involved as an interpreter for the chief Standing Bear and an expert witness on Indian issues. She invited Francis to accompany her with Standing Bear on a lecture tour of the eastern United States during 1879-1880. They took turns acting as interpreter for the chief.

In 1881 Susette and the journalist Thomas Tibbles accompanied Alice C. Fletcher, an anthropologist, on her unprecedented trip to live with and study Sioux women on the Rosebud Indian Reservation.[2] Susette acted as her interpreter. Francis La Flesche also met and assisted Fletcher at this time, and they started a lifelong professional partnership.

Nearly 20 years older than he, Fletcher encouraged his education to become a professional anthropologist. He started working with her in Washington, D.C., about 1881, where he also worked as an interpreter for the US Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.[3]

La Flesche gained a position with the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution, with which Fletcher collaborated on her research. He served as a copyist, translator and interpreter. At the beginning, he helped classify Omaha and Osage artifacts. He advanced to conducting professional-level research with Fletcher, and also acted as her translator and interpreter. He graduated from the National University Law School (now George Washington University Law School) in 1892 and earned a master's degree there in 1893.[3] In 1891 Fletcher had informally adopted the 34-year-old La Flesche.[3]

In their joint book and articles on the Omaha, La Flesche followed the anthropological approach of describing rituals and practices in detail. During his regular visits to the Omaha and Osage, and study of their rituals, La Flesche also made recordings on wax cylinders (now invaluable) of their songs and chants, as well as documenting them in writing. The young composer Charles Wakefield Cadman was interested in American Indian music and influenced by La Flesche's work.[4] Cadman spent time on the Omaha reservation to learn many songs and how to play the traditional instruments.

In 1908 La Flesche proposed a collaboration with Cadman and Nelle Richmond Eberhart, to create an opera based on his Omaha stories. Eberhart had written lyrics for Cadman's Four American Indian Songs, as well as other of his songs. The team worked for four years on Da O Ma, which was changed to feature Sioux characters. Each approached the collaboration from a different point of view, and the opera was never published or performed.[4][5] LaFlesche contributed also to Cadman's ''The Robin Woman (Shanewis) (1918), but the composer completed the project with Tsianina Redfeather Blackstone, a Creek singer who contributed to the libretto.[5]

Beginning in 1910, La Flesche gained a professional position as an anthropologist in the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology, serving there until 1929. This marked the second part of his career. He wrote and lectured extensively on his research, publishing most of his works during this time. His focus changed with his independent research on the music and religion of the Osage, who are closely related to the Omaha.

His primary objective was to explain Osage ideas, beliefs, and concepts. He wanted his readers to see the world of the Osages for what it was in reality-not the world of simple "children of nature" but a highly complex world reflecting an intellectual tradition as sophisticated and imaginative as that of any Old World people.[6]

Wax cylinder recordings

editLa Flesche recorded on wax cylinders. His recordings are held by the Library of Congress, and digitized versions of more than 60 are available online.[7] Contemporary Osage tribal members have compared the effect of hearing the recordings of their traditional rituals to that of Western scholars reading the newly discovered Dead Sea Scrolls.[8]

Marriage and family

editLa Flesche married Alice Mitchell in June 1877, but she died the next year.[9] In 1879 he married Rosa Bourassa, a young Omaha woman, about the time of his tour in 1879-1880 with his sister and Standing Bear. They separated shortly before he began working in Washington, D.C., in 1881 and divorced in 1884.[6][9]

For most of his years in Washington, La Flesche shared a house on Capitol Hill with Alice Fletcher, with whom he worked closely, and Jane Gay.[9] Fletcher and La Flesche kept the nature of their relationship private. She willed money to him at her death.[6]

Death

editFrancis La Flesche died on September 5, 1932, in Thurston County, Nebraska. He was buried in Bancroft Cemetery, Bancroft, Nebraska, near the graves of his father and half-sisters Susette La Flesche and Rosalie La Flesche.

Legacy and honors

edit- 1922, La Flesche was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences

- 1922-23, he was elected as president of the Anthropological Society of Washington

- 1926, awarded an Honorary Doctor of Letters by the University of Nebraska[3]

- Because of the close working relationship between Fletcher and La Flesche, the Smithsonian Institution has collected their papers in a joint archive.[3]

Works

edit- 1900, The Middle Five: Indian Boys at School (memoir)

- 1911, The Omaha Tribe, with Alice Cunningham Fletcher

- 1912, Da O Ma (unpublished)[10]

- 1914/-1915/1921, The Osage Tribe: Rite of Chiefs[10]

- 1917-1918/1925, The Osage Tribe: the Rite of Vigil[10]

- 1925-1926/1928, The Osage Tribe: Two Versions of the Child-Naming Rite[10]

- 1927-1928/1930, The Osage Tribe: Rite of the Waxo'be[10]

- 1932, Dictionary of the Osage Language (linguistics)

- 1939, War Ceremony and Peace Ceremony of the Osage Indians, published posthumously[3]

- 1999, The Osage and the Invisible World, edited by Garrick A. Bailey[11]

- 1998 Ke-ma-ha: The Omaha Stories of Francis La Flesche, edited by Daniel Littlefield and James Parins, Nebraska University Press, previously unpublished work[10]

References

edit- ^ LaFlesche Family Papers[usurped], Nebraska State Historical Society, accessed 22 August 2011

- ^ Camping With the Sioux: Fieldwork Diary of Alice Cunningham Fletcher Archived 2011-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, National Museum of Natural History, Archives of the Smithsonian Institution, accessed 26 August 2011

- ^ a b c d e f "Register to the Papers of Alice Cunningham Fletcher and Francis La Flesche" Archived 2009-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

- ^ a b Introduction, Francis La Flesche, Ke-ma-ha: The Omaha Stories of Francis La Flesche, Lincoln: Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 1998, accessed 26 August 2011

- ^ a b Pamela Karantonis, Dylan Robinson. Opera Indigene: Re/presenting First Nations and Indigenous Cultures, Routledge, 2016, p. 178

- ^ a b c Introduction, The Osage and the Invisible World, edited by Garrick A. Bailey, University of Oklahoma Press, 1999, 26 August 2011

- ^ "Library of Congress; Contributor: La Flesche, Francis". loc.gov. US Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Time Life Books. (1993). The Wild West, Time Life Books, p. 318

- ^ a b c Joan T. Mark, A Stranger in Her Native Land: Alice Fletcher and the American Indians, University of Nebraska Press, 1988, p. 308

- ^ a b c d e f "Francis La Flesche, The Cambridge Companion to Native American Literature, edited by Joy Porter, Kenneth M. Roemer, Cambridge University Press, 2005, accessed 26 August 2011

- ^ The Osage and the Invisible World, edited by Garrick A. Bailey, University of Oklahoma Press, 1999, 26 August 2011

Further reading

edit- Green, Norma Kidd, Iron Eye's Family: The Children of Joseph LaFlesche, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1969.

- Liberty, Margot, "Native American 'Informants': The Contribution of Francis La Flesche", in American Anthropology: The Early Years, ed. by John V. Murra, 1974 Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society. St. Paul: West Publishing Co. 1976, pp. 99–110

- Liberty, Margot, "Francis La Flesche, Omaha, 1857—1932", in American Indian Intellectuals, ed. by Margot Liberty, 1976 Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society. St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1978, pp. 45–60

- Mark, Joan (1982). "Francis La Flesche: The American Indian as Anthropologist", in Isis 73(269)495—510.

External links

edit- Works by Francis La Flesche at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Francis La Flesche in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- "Francis La Flesche", American Memory, Library of Congress

- Omaha Indian Music, Library of Congress. Recordings of traditional Omaha music by Francis La Flesche from the 1890s, as well as recordings and photographs from the late 20th century.

- "Register to the Papers of Alice Cunningham Fletcher and Francis La Flesche", National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

- Finding Aid to LaFlesche Family papers, at History Nebraska

- "Francis La Flesche". Find A Grave. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "Joseph "Insta Maza" La Flesche". Find a Grave. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2015.