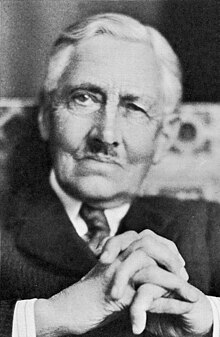

Sir Frederic Truby King CMG (1 April 1858 – 10 February 1938), generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society.

Sir Truby King | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Frederic Truby King 1 April 1858 New Plymouth, New Zealand |

| Died | 10 February 1938 (aged 79) Wellington, New Zealand |

| Occupation(s) | Bank clerk, asylum superintendent, child health reformer |

| Known for | Founder of Plunket Society |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Newton King (brother) |

Early life

editKing was born in New Plymouth on 1 April 1858, the son of Thomas and Mary King.[1] His brother, Newton King, was to become a leading Taranaki businessman. Truby King was privately educated by Henry Richmond and proved to be a keen scholar. After working for a short time as a bank clerk he travelled to Edinburgh and Paris to study medicine.[2] In 1886, he graduated with honours with a M.B., C.M, and later completed a BSc in Public Health (Edinburgh). Although his interest was in surgery it was the demonstrations of Charcot on hysteria and neurological disorders that influenced his choice of career. While training in Scotland he married Isabella Cockburn Miller.[2] Around 1904, King and his wife adopted the infant daughter of Leilah Gordon when Gordon's husband was sick, a decision that Gordon regretted for the rest of her life.[3] The baby, named Esther Loreena, became known as Mary King.[3]

Medical appointments

editIn 1887, while still in Scotland, King was appointed resident surgeon at both the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and Glasgow Royal Infirmary.[2] Returning to New Zealand he became Medical Superintendent of the Wellington General Hospital from 1888 to 1889.[4] By 1889 he was in Dunedin as Medical Superintendent at the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum and as a lecturer in mental diseases at the University of Otago.[2]

At Seacliff he introduced better diets for patients, more discipline for staff and improvements to the hospital farm.[2] The 'villa' style of treatment, with smaller and more open wards, was also one of his innovations. These reforms and King's own intransigence to those who opposed them led to a Commission of Inquiry, which completely vindicated his methods.

Developing interest in infant care and nutrition

editOver the next eight years, King had interests in psychology, medicine, agriculture, horticulture, child care and alcoholism. He began to realise that principles of nutrition applied across many disciplines.[2] He spent a winter in Japan during the Russo-Japanese War and returned with his dream clarified, having noticed how healthy infants were due to 12 to 18 months of breastfeeding.[2] On his return he began to use his access as a Justice of the Peace to licensed baby-boarding homes where typical conditions moved him to establish such a boarding facility himself at his Karitane residence at the foot of Huriawa Peninsula.[2]

Plunket Society

editIt is the establishment of the Plunket Society on 14 May 1907 for which King is best known. Set up to apply scientific principles to nutrition of babies, and strongly rooted in eugenics and patriotism,[5] its 1917 "Save the Babies" Week had the slogan "The Race marches forward on the feet of Little Children".,[6]

King's methods to teach mothers domestic hygiene and childcare were strongly promoted through his first book on mothercare, Feeding and Care of Baby, and via a network of specially trained Karitane nurses and a widely syndicated newspaper column, Our babies, written by King's wife Isabella. Apart from nutrition, King's methods specifically emphasised regularity of feeding, sleeping and bowel movements, within a generally strict regimen supposed to build character by avoiding cuddling and other attention.[5]

His methods were controversial. In 1914 the physician Agnes Elizabeth Lloyd Bennett publicly opposed his stance that higher education for women was detrimental to their maternal functions and hence to the human race.[7] He also excited controversy during his efforts to export his methods to Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, with particular debate associated with his views on infant feeding formulas. He believed in "humanized" milk with the protein reduced to 1.4% to match breast milk, against the general paediatric consensus at the time in favour of high protein feeds.[8]

The work of the Plunket Society was credited with lowering infant mortality in New Zealand from 88 per thousand in 1907 to 32 per thousand over the next thirty years, though it has since been argued that this was due less to its specific methods than to its general raising of awareness of childcare.[8]

Public service

editKing was appointed to represent New Zealand in 1913 at the Child Welfare Conference in London and was invited to assist in the establishment of a child public health service in Britain. In 1917 the former patron of the Plunket Society, Lady Victoria Plunket, wife of the former Governor of New Zealand, William Plunket, 5th Baron Plunket,[9] invited Truby King to come to London to set up an infant welfare centre. It became the Babies of the Empire Society, later renamed the Mothercraft Training Society.

Following the First World War he was one of the British representatives at the Inter-allied Red Cross Conference and travelled through Europe for the War Victims Relief Committee.

Back in New Zealand, by 1921, King became Director of Child Welfare in the Department of Health and by 1925 also Inspector-General of Mental Hospitals. Until his retirement in 1927, he continued to develop and organise mental hospital services in New Zealand. His work was recognised by the award of a CMG in 1917 and a knighthood in 1925. In 1935, he was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal.[10]

Later years

editKing died in Wellington on 10 February 1938. He was the first private citizen in New Zealand to be given a state funeral.[11]

Twenty years later, he was the first New Zealander to feature on a New Zealand postage stamp.[11]

His babycare method continued in popularity, finding favour in post-war Britain at least until the 1950s.[12]

It featured, controversially, in the 2007 Channel 4 documentary series, Bringing Up Baby, which compared it with the 1960s Benjamin Spock and the 1970s Continuum concept.[12]

Legacy

editFour streets in New Zealand are named after King: Truby King Street in the New Plymouth suburb of Merrilands, Truby King Street in Rolleston, Truby King Crescent in the Dunedin suburb of Liberton, and Truby King Drive in Waikouaiti.

Truby King Recreation Reserve: A public nature reserve located in Seacliff

Truby King Park, in Melrose, Wellington, includes the Truby King Mausoleum.

In Australia a number of maternal childhood centres in the 20's, 30's, and 40's were named after Truby King such as Coburg and Dandenong (both in Melbourne).[13] One such centre, in the Melbourne suburb of Coburg is now a heritage listed building.[14]

References

edit- ^ "Death of an old Settler". The Star. No. 4630. 28 April 1893. p. 3. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h From the pen of F Truby King, Truby King Booklet Committee, Auckland, undated

- ^ a b New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga. "Gordon, Eliza". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Barber, L.; Towers, R.J. (1976). Wellington hospital 1847-1976. Wellington Hospital Board. p. 134. OCLC 4179287.

- ^ a b Gene Dreaming: New Zealanders and Eugenics Archived 9 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Hilary Stace, Professional Historians' Association of New Zealand/Aotearoa (PHANZA), September 1997,

- ^ New Zealand's Infant Welfare Services and Maori, 1907–60 Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Linda Bryder, Health and History, Volume 3, Number 1, 2001

- ^ Bennett, Agnes Elizabeth Lloyd (1872–1960), Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ a b Philippa Mein Smith, "King, Sir (Frederic) Truby (1858–1938)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 4 Nov 2007

- ^ Rowald, Katharina (17 December 2018). "'If We Are to Believe the Psychologists …': Medicine, Psychoanalysis and Breastfeeding in Britain, 1900–55". Medical History. 63 (1). Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Official jubilee medals". Evening Post. 6 May 1935. p. 4. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ a b Nigel Benson, "Seacliff asylum's painful and haunting history" Otago Daily Times, Dunedin 27 January 2007

- ^ a b Frederic Truby King's Strict Routine Method, Channel 4 Bringing up Baby microsite

- ^ "Infant Welfare". The Dandenong Journal. Victoria, Australia. 17 March 1932. p. 8. Retrieved 11 June 2020 – via Trove.?

- ^ "Truby King Baby Health Centre". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Council Victoria. Retrieved 10 June 2020.