French Americans or Franco-Americans (French: Franco-américains) are citizens or nationals of the United States who identify themselves with having full or partial French or French-Canadian heritage, ethnicity and/or ancestral ties.[2][3][4] They include French-Canadian Americans, whose experience and identity differ from the broader community.

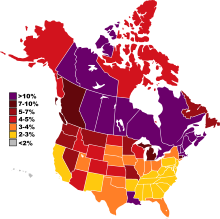

French Americans and French Canadians as percent of population by state and province.[a] | |

| Total population | |

| Including French-Canadian: 8,053,902 (2.4%) alone or in combination | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Predominantly in New England and Louisiana with smaller communities elsewhere; largest numbers in California. Significant communities also exist in New York, Wisconsin, and Michigan, as well as throughout the Mid-Atlantic. | |

| Languages | |

| French, Louisiana Creole, English, Franglais | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christian (Majority Catholic, minority Protestant) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| French Canadians, French-Canadian Americans, Basque Americans, Belgian Americans (Wisconsin Walloons), Breton Americans, Catalan Americans, Corsican Americans |

The state with the largest proportion of people identifying as having French ancestry is Maine, while the state with the largest number of people with French ancestry is California. Many U.S. cities have large French American populations. The city with the largest concentration of people of French extraction is Madawaska, Maine, while the largest French-speaking population by percentage of speakers in the U.S. is found in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana.

Country-wide, as of 2020, there are about 9.4 million U.S. residents who declare French ancestry[5] or French Canadian descent, and about 1.32 million[6] per the 2010 census, spoke French at home.[7][8] An additional 750,000 U.S. residents speak a French-based creole language, according to the 2011 American Community Survey.[9]

Franco-Americans are less visible than other similarly sized ethnic groups and are relatively uncommon when compared to the size of France's population, or to the numbers of German, Italian, Irish or English Americans. This is partly due to the tendency of Franco-American groups to identify more closely with North American regional identities such as French Canadian, Acadian, Brayon, Louisiana French (Cajun, Creole) than as a coherent group, but also because emigration from France during the 19th century was low compared to the rest of Europe. Consequently, there is less of a unified French American identity as with other European American ethnic groups, and Americans of French descent are highly concentrated in New England and Louisiana. Nevertheless, the French presence has had an outsized impact on American toponyms.

History

editSome Franco-Americans arrived prior to the founding of the United States, settling in places like the Midwest, Louisiana or Northern New England. In these same areas, many cities and geographic features retain their names given by the first Franco-American inhabitants, and in sum, 23 of the Contiguous United States were colonized in part by French pioneers or French Canadians, including settlements such as Iowa (Des Moines), Missouri (St. Louis), Kentucky (Louisville) and Michigan (Detroit), among others.[10] Settlers and political refugees from the Kingdom of France, including Huguenots, also settled alongside French-speaking Flemish Walloons in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, the capital of New Netherland, which later became New York City.[11][12] While found throughout the country, today Franco-Americans are most numerous in New England, northern New York, the Midwest, Louisiana, and northern California. Often, Franco-Americans are identified more specifically as being of French Canadians, Cajuns or Louisiana Creole descent.[13]

A vital segment of Franco-American history involves the Quebec diaspora of the 1840s–1930s, in which nearly one million French Canadians moved to the United States, mainly relocating to New England mill towns, fleeing economic downturn in Québec and seeking manufacturing jobs in the United States. Historically, French Canadians had among the highest birth rates in world history, explaining their relatively large population despite low immigration rates from France. These immigrants mainly settled in Québec and Acadia, although some eventually inhabited Ontario and Manitoba. Many of the first French-Canadian migrants to the U.S. worked in the New England lumber industry, and, to a lesser degree, in the burgeoning mining industry in the upper Great Lakes. This initial wave of seasonal migration was then followed by more permanent relocation in the United States by French-Canadian millworkers.

Louisiana

editLouisiana Creole people refers to those who are descended from the colonial settlers in Louisiana, especially those of French and Spanish descent but also including individuals of mixed-race heritage (cf. Creoles of Color). Louisiana Creoles of any race have common European heritage and share cultural ties, such as the traditional use of the French language and the continuing practice of Catholicism; in most cases, the people are related to each other. Those of mixed race also sometimes have African and Native American ancestry.[14] As a group, the mixed-race Creoles rapidly began to acquire education, skills (many in New Orleans worked as craftsmen and artisans), businesses and property. They were overwhelmingly Catholic, spoke Colonial French (although some also spoke Louisiana Creole) and kept up many French social customs, modified by other parts of their ancestry and Louisiana culture. The free people of color married among themselves to maintain their class and social culture.

The Cajuns of Louisiana have a unique heritage, generally seeing themselves as distinct from Louisiana Creoles despite a number of historical documents also classifying the Acadians' descendants as Créoles. Their ancestors settled Acadia, in what is now the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and part of Maine in the 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1755, after capturing Fort Beauséjour and several other French forts in the region, British authorities demanded the Acadians swear an oath of loyalty to the British Crown, which the majority refused to do. In response, the British deported them to the Thirteen Colonies in the south in what has become known as the expulsion of the Acadians. Over the next generation, some four thousand Acadians made the long trek to Louisiana, where they began a new life. The name Cajun is a corruption of the word Acadian. Many still live in what is known as the Cajun Country, where much of their colonial culture survives. French Louisiana, when it was sold by Napoleon in 1803, covered all or part of fifteen current U.S. states and contained French and Canadian colonists dispersed across it, though they were most numerous in its southernmost portion.

During the War of 1812, Louisiana residents of French origin took part on the American side in the Battle of New Orleans (December 23, 1814, through January 8, 1815). Jean Lafitte and his Baratarians later were honored by US General Andrew Jackson for their contribution to the defense of New Orleans.[15]

In Louisiana today, more than 15 percent of the population of the Cajun Country reported in the 2000 United States Census that French was spoken at home.[16]

Another significant source of immigrants to Louisiana was Saint-Domingue (today Haiti); many Saint Dominicans fled during this time, and half of the diaspora eventually settled in New Orleans.[17]

Biloxi in Mississippi, and Mobile in Alabama, still contain French American heritage since they were founded by the Canadian Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville.

The Houma Tribe in Louisiana still speak the same French they had been taught 300 years ago.

Colonial era

editIn the 17th and early 18th centuries, there was an influx of a few thousand Huguenots, who were Calvinist refugees fleeing religious persecution following the issuance of the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau by Louis XIV of the Kingdom of France.[18] Some of these refugees settled in the Dutch colony of New Netherland and its capital city, New Netherland, including being among the first Europeans to settle on Staten Island.[12] In 1674, with the signing of the Treaty of Westminster to end the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674), the Netherlands ceded the colony to Great Britain, who renamed the colony New York, and its capital to New York City, after Prince James, Duke of York, the brother of King Charles II of England.

For nearly a century, French settlers fostered a distinctive French Protestant identity that enabled them to remain aloof from American society, but by the time of the American Revolution, they had generally intermarried and merged into the larger Presbyterian community.[19] In 1700, they constituted 13% of the white population of the Province of Carolina, and 5% of the white population of the Province of New York.[18] The largest number settling in South Carolina, where the French comprised 4% of the white population in 1790.[20][21] With the help of the well-organized international Huguenot community, many also moved to Virginia.[22] In the north, Paul Revere of Boston was a prominent figure.

A new influx of French-heritage people occurred at the very end of the colonial era. Following the failed invasion of Quebec in 1775-1776, hundreds of French-Canadian men who had enlisted in the Continental Army remained in the ranks. Under colonels James Livingston and Moses Hazen, they saw military action across the main theaters of the Revolutionary War. At the end of the war, New York State formed the Canadian and Nova Scotia Refugee Tract stretching westward from Lake Champlain. Though many of the veterans sold their claim in this vast region, some remained and the settlement held. From early colonizing efforts in the 1780s to the era of Quebec's "great hemorrhage," the French-Canadian presence in Clinton County in northeastern New York was inescapable.[23]

Midwest

editFrom the beginning of the 17th century, French Canadians explored and traveled to the region with their coureur de bois and explorers, such as Jean Nicolet, Robert de LaSalle, Jacques Marquette, Nicholas Perrot, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, Pierre Dugué de Boisbriant, Lucien Galtier, Pierre Laclède, René Auguste Chouteau, Julien Dubuque, Pierre de La Vérendrye and Pierre Parrant.

The French Canadians set up a number of villages along the waterways, including Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; La Baye, Wisconsin; Cahokia, Illinois; Kaskaskia, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan; Saint Ignace, Michigan; Vincennes, Indiana; St. Paul, Minnesota; St. Louis, Missouri; and Sainte Genevieve, Missouri. They also built a series of forts in the area, such as Fort de Chartres, Fort Crevecoeur, Fort Saint Louis, Fort Ouiatenon, Fort Miami (Michigan), Fort Miami (Indiana), Fort Saint Joseph, Fort La Baye, Fort de Buade, Fort Saint Antoine, Fort Crevecoeur, Fort Trempealeau, Fort Beauharnois, Fort Orleans, Fort St. Charles, Fort Kaministiquia, Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Rouillé, Fort Niagara, Fort Le Boeuf, Fort Venango and Fort Duquesne. The forts were serviced by soldiers and fur trappers who had long networks reaching through the Great Lakes back to Montreal.[24] Sizable agricultural settlements were established in the Pays des Illinois.[25]

The region was relinquished by France to the British in 1763 as a result of the Treaty of Paris. Three years of war by the Natives, called Pontiac's War, ensued. It became part of the Province of Quebec in 1774, and was seized by the United States during the Revolution.[26]

New England and New York State

editIn the nineteenth century, many people of French heritage arrived from Quebec and New Brunswick to work in manufacturing cities, especially textile centers, in New England and New York State. They came together in enclaves known as "Little Canadas". In the same period, Francophones from Quebec became a majority of workers in other regions and sectors, for instance the saw mill and logging camps in the Adirondack Mountains and their foothills. They amounted to an ever-growing share of the region's population; by the mid-twentieth century, Franco-Americans comprised 30 percent of Maine's population.[27]

Factories could provide employment to entire nuclear families, including children. Some French-Canadian women saw New England as a place of opportunity and possibility where they could create economic alternatives for themselves distinct from the expectations of their farm families in Canada. By the early twentieth century, some saw temporary migration to the United States as a rite of passage and a time of self-discovery and self-reliance. Most moved permanently to the United States, using the inexpensive railroad system to visit Quebec from time to time. When these women did marry, they had fewer children with longer intervals between children than their Canadian counterparts. Some women never married and oral accounts suggest that self-reliance and economic independence were important reasons for choosing work over marriage and motherhood. These women conformed to traditional gender ideals in order to retain their 'Canadienne' cultural identity, but they also redefined these roles in ways that provided them increased independence as wives and mothers.[28][29] Women also shaped the Franco-American experience as members of religious orders. The first hospital in Lewiston, Maine, became a reality in 1889 when the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, the 'Grey Nuns,' opened the Asylum of Our Lady of Lourdes. This hospital was central to the Grey Nuns' mission of providing social services for Lewiston's predominately French-Canadian mill workers. The Grey Nuns struggled to establish their institution despite meager financial resources, language barriers, and opposition from the established medical community.[30][31]

The French-Canadian community in the Northeast tried to preserve its inherited cultural norms. This happened within the institutions of the Catholic Church, though it involved struggling with little success against Irish clerics. According to Raymond Potvin, the predominantly Irish hierarchy was slow to recognize the need for French-language parishes; several bishops even called for assimilation and English language-only parochial schools. By the twentieth century, a number of parochial schools for Francophone students opened, though they gradually closed later in the century and a large share of the French-speaking population left the Church. At the same time, the number of priests available to staff these parishes diminished.[32] Like Church institutions, such Franco-American newspapers as Le Messager and La Justice served as pillars of the ideology of survivance—the effort to preserve the traditional culture through faith and language.[33] A product of the commercial and industrial economy of these areas, by 1913, the French and French-Canadian populations of New York City, Fall River (Massachusetts), and Manchester (New Hampshire) were the largest in the country. Out of the 20 largest Franco-American populations in the United States, only four cities were outside of New York and New England, with New Orleans ranking 18th largest in the nation.[34] Because of this, a number of French institutions were established in New England, including the Société Historique Franco-américaine in Boston and the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste d’Amérique of Woonsocket, the largest French-Catholic cultural and mutual benefit society in the United States in the early twentieth century.[35] Immigration from Quebec dwindled in the 1920s.

Amid the decline of the textile industry from the 1920s to the 1950s, the French element experienced a period of upward mobility and assimilation. This pattern of assimilation increased during the 1970s and 1980s as many Catholic organizations switched to English and parish children entered public schools; some parochial schools closed in the 1970s.[27][36] In recent decades, self-identification has moved away from the French language.

Franco-American culture continues to evolve in the twenty-first century. Well-established genealogical societies and public history venues still seek to share the Franco-American story. Their work is occasionally supported by the commercial and cultural interests of Quebec and state governments in the Northeast.[37] New groups and events have contributed to the effort. Some observers have drawn a comparison between recent developments and the appropriation and modernization of “Franco” culture by young people in the 1970s. For some, a “renaissance” or “revival” is under way.[38][39]

The New Hampshire PoutineFest, founded by Timothy Beaulieu, uses an iconic Quebec dish to broaden interest in the culture.[40] The French-Canadian Legacy podcast offers contemporary perspectives on French-Canadian experiences on both sides of the border. Through a collaboration with the Quebec Government Office and local institutions, the podcast’s team established a GeoTour dedicated to Franco-American life in major New England cities.[41] Acts of commemoration have lately extended to pioneer suffragist Camille-Lessard Bissonnette.[42] Abby Paige has, for her part, brought the community’s history and its complicated legacies to the stage.[43] The culture and its manifestations in Louisiana, the Midwest, and the Northeast have become the focus of a course at Harvard University.[44] Francophonie Month (March) and St. John the Baptist Day (June 24) also provide an opportunity for celebration and increased visibility.[45] At the same time, some members of the community are inviting reconsideration of Franco-Americans’ place in conversations about race[46][47] and class.[48]

Noted American popular culture figures who maintained a close connection to their French roots include musician Rudy Vallée (1901–1986) who grew up in Westbrook, Maine, a child of a French-Canadian father and an Irish mother,[49] and counter-culture author Jack Kerouac (1922–1969) who grew up in Lowell, Massachusetts. Kerouac was the child of two French-Canadian immigrants and wrote in both English and French. Franco-American political figures from New England include U.S. Senator Kelly Ayotte (R, New Hampshire), Governor Paul LePage of Maine, and Presidential adviser Jon Favreau, who was born and raised in Massachusetts.

California

editDuring the early years of the California Gold Rush, over 20,000 migrants from France arrived in the state.[50] By the mid-1850s, San Francisco had emerged as the center of the French population on the West Coast, with over 30,000 people of French descent, more than any other ethnic group except Germans.[51] During this period, the city's French Quarter was established, along with important businesses and institutions such as the Boudin Bakery and French Hospital. Since the US was in high demand for labor between 1921 and 1931, it resulted in an estimated 2 million French immigrants coming to America for jobs. This not only portrayed a strong impact on the American economy, but also the French economy as well.[52] The latter half of the 19th century progressed, French immigrants continued to arrive in San Francisco in large numbers and French entrepreneurs played significant roles in shaping the city's culinary, fashion, and financial sectors. This led to the city earning the nickname "Paris of the Pacific".[53]

French immigrants and their descendants also began settling in what is now the North Bay, becoming instrumental in the development of Wine Country and the modern California wine industry.[54] Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, French architecture (especially Beaux-Arts) was heavily used in the rebuilding of the city, as evidenced in its City Hall, Legion of Honor Museum, and downtown news kiosks.[51]

As a result of historic connections and cultural exchanges between France and the region, the majority of French multinational businesses have established their U.S. headquarters or subsidiaries in the San Francisco Bay Area since the rise of Silicon Valley and the Dot-com bubble.[55]

Civil War

editFranco-Americans in the Union forces were one of the most important Catholic groups present during the American Civil War. The exact number is unclear, but thousands of Franco-Americans appear to have served in this conflict. Union forces did not keep reliable statistics concerning foreign enlistments. However, historians have estimated anywhere from 20,000 to 40,000 Franco-Americans serving in this war. In addition to those born in the United States, many who served in the Union forces came from Canada or had resided there for several years. Canada's national anthem was written by such a soldier named Calixa Lavallée, who wrote this anthem while he served for the Union, attaining the rank of Lieutenant.[56] Leading Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard was a notably francophone Louisiana Creole.

Politics

editWalker (1962) examines the voting behavior in U.S. presidential elections from 1880 to 1960, using election returns from 30 Franco-American communities in New England, along with sample survey data for the 1948–60 elections. According to Walker, from 1896 to 1924, Franco-Americans typically supported the Republican Party because of its conservatism, emphasis on order, and advocacy of the tariff to protect the textile workers from foreign competition. In 1928, with Catholic Al Smith as the Democratic candidate, the Franco-Americans moved over to the Democratic column and stayed there for six presidential elections. They formed part of the New Deal Coalition. Unlike the Irish and German Catholics, very few Franco-Americans deserted the Democratic ranks because of the foreign policy and war issues of the 1940 and 1944 campaigns. In 1952 many Franco-Americans broke from the Democrats but returned heavily in 1960.[57]

Additional work has expanded Walker's findings. Ronald Petrin has explored the rise of the Republican ascendency among Massachusetts Franco-Americans in the 1890s; the lengthy economic depression that coincided with President Grover Cleveland's administration and Franco-Irish religious controversies were likely factors in growing support for the GOP. Petrin recognizes different political behaviors in large cities and in smaller centers.[58] Madeleine Giguère has confirmed the later shift to the Democratic column through her research on Lewiston's presidential vote during the twentieth century.[59] In the most in-depth study of Franco-American political choices, Patrick Lacroix finds different patterns of partisan engagement across New England and New York State. In southern New England, Republicans actively courted the "Franco" vote and offered nominations. The party nominated Aram J. Pothier, a native of Quebec, who won his bid for the governorship of Rhode Island and served seven terms in that office. In northern New England, Franco-Americans faced exclusion from the halls of power and more easily turned towards the Democrats. During the 1920s, the regional disparity disappeared. Due to the nativist and anti-labor policies of Republican state governments, an increasingly unionized Franco-American working class lent its support to the Democrats across the region. Elite "Francos" continued to prefer the GOP.[60]

As the ancestors of most Franco-Americans had for the most part left France before the French Revolution, they usually prefer the fleur-de-lis to the modern French tricolor.[61]

Franco-American Day

editIn 2008, the state of Connecticut made June 24 Franco-American Day, recognizing French Canadians for their culture and influence on Connecticut. The states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, have now also held Franco-American Day festivals on June 24.[62]

Demographics

editColonial French American population in 1790

editThe Census Bureau produced estimates of the colonial American population with roots in France, in collaboration with the American Council of Learned Societies, by scholarly classification of the names of all White heads of families recorded in the first U.S. census of 1790. The government required accurate counts of the origins of colonial stock as basis for computing National Origins Formula immigration quotas in the 1920s; for this task scholars estimated the proportion of names in each state determined to be of French derivation. The report concluded that, in 1790, French Americans made up roughly 2.3% of the population inhabiting the Continental United States; the highest concentrations of French Americans resided in the territories that had historically formed colonial New France to the west of British America. Within the Thirteen Colonies, the most significant French minorities could be found in the Middle Colonies of New York and New Jersey, and the Southern Colonies of South Carolina and Georgia.

Estimated French American population in the Continental United States as of the 1790 Census [63]

| State or Territory | French | |

|---|---|---|

| # | % | |

| Connecticut | 2,100 | 0.90% |

| Delaware | 750 | 1.62% |

| Georgia | 1,200 | 2.27% |

| Kentucky & Tenn. | 2,000 | 2.15% |

| Maine | 1,200 | 1.25% |

| Maryland | 2,500 | 1.20% |

| Massachusetts | 3,000 | 0.80% |

| New Hampshire | 1,000 | 0.71% |

| New Jersey | 4,000 | 2.35% |

| New York | 12,000 | 3.82% |

| North Carolina | 4,800 | 1.66% |

| Pennsylvania | 7,500 | 1.77% |

| Rhode Island | 500 | 0.77% |

| South Carolina | 5,500 | 3.92% |

| Vermont | 350 | 0.41% |

| Virginia | 6,500 | 1.47% |

| 1790 Census Area | 54,900 | 1.73% |

| Northwest Territory | 6,000 | 57.14% |

| French America | 12,850 | 64.25% |

| Spanish America | − | - |

| United States | 73,750 | 2.29% |

2000 Census

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau of 2000, 5.3 percent of Americans are of French or French Canadian ancestry. In 2013 the number of people living in the U.S. who were born in France was estimated at 129,520.[64] Franco-Americans made up close to, or more than, 10 percent of the population of seven states, six in New England and Louisiana. Population wise, California has the greatest Franco population followed by Louisiana, while Maine has the highest by percentage (25 percent).

|

|

|

|

Historical immigration

edit

Between 1820 and 1920, 530,000 French people came to the United States |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religion

editMost Franco Americans have a Roman Catholic heritage (which includes most French Canadians and Cajuns). Protestants would arrive in two smaller waves, with the earliest arrivals being the Huguenots who fled from France in the colonial era, many of whom would settle in Boston, Charleston, New York and Philadelphia.[69] Huguenots and their descendants would immigrate to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Provinces of Pennsylvania and Carolina due in large part to colonial anti-Catholic sentiment, during the period of the Edict of Fontainebleau.[70] The 19th century would see the arrival of others from Switzerland.[71]

From the 1870s to the 1920s in particular, there was tension between the English-speaking Irish Catholics, who dominated the Church in New England, and the French-Canadian immigrants, who wanted their language taught in the parochial schools. The Irish controlled all the Catholic colleges in New England, except for Assumption College in Massachusetts, controlled by the French and one school in New Hampshire controlled by Germans. Tensions between these two groups bubbled up in Fall River in 1884–1886, in Danielson, Connecticut and North Brookfield, Massachusetts in the 1890s and in Maine in the subsequent decades.[72][73][74][75] A breaking point was reached during the Sentinelle affair of the 1920s, in which Franco-American Catholics of Woonsocket,[76] Rhode Island, challenged their bishop over control of parish funds in an unsuccessful bid to wrest power from the Irish American episcopate.[77] In a 1957 treatise on urban history, American historian Constance Green would attribute some disputes between French and Irish Catholics in Massachusetts, Holyoke in particular, as fomented by Yankee English Protestants, in the hopes that a split would diminish Catholic influence.[78]

Marie Rose Ferron was a mystic stigmatic; she was born in Quebec and lived in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Between about 1925 and 1936, she was a popular "victim soul" who suffered physically to redeem the sins of her community. Father Onésime Boyer promoted her cult.[79]

Education

editCurrently there are multiple French international schools in the United States operated in conjunction with the Agency for French Education Abroad (AEFE).[80]

French language in the United States

editAccording to the National Education Bureau, French is the second most commonly taught foreign language in American schools, behind Spanish. The percentage of people who learn French language in the United States is 12.3%.[64] French was the most commonly taught foreign language until the 1980s; a subsequent influx of Hispanic immigrants aided the growth of Spanish into the 21st century. According to the U.S. 2000 Census, French is the third most spoken language in the United States after English and Spanish, with 2,097,206 speakers, up from 1,930,404 in 1990. The language is also commonly spoken by Haitian immigrants in Florida and New York City.[81]

As a result of French immigration to what is now the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries, the French language was once widely spoken in a few dozen scattered villages in the Midwest. Migrants from Quebec after 1860 brought the language to New England. French-language newspapers existed in many American cities; especially New Orleans and in certain cities in New England. Americans of French descent often lived in predominantly French neighborhoods; where they attended schools and churches that used their language. Before 1920 French Canadian neighborhoods were sometimes known as "Little Canada".[82]

After 1960, the "Little Canadas" faded away.[83] There were few French-language institutions other than Catholic churches. There were some French newspapers, but they had a total of only 50,000 subscribers in 1935.[84] The World War II generation avoided bilingual education for their children, and insisted they speak English.[85] By 1976, nine in ten Franco Americans usually spoke English and scholars generally agreed that "the younger generation of Franco-American youth had rejected their heritage."[86]

Flag

editThe Franco-American flag is an ethnic flag adopted at a Franco-American conference at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire in May 1983 to represent their New England community. It was designed by Robert L. Couturier, attorney and one-time mayor of Lewiston, Maine, to have a blue field with a white fleur-de-lis over a white five-pointed star.[87][88] This flag extends a tradition of designing flags for the French communities of each Canadian province to the United States.

Blue and white are colors found on the flags of both the United States and francophone nations such as France or Quebec. The star symbolizes the United States and the fleur-de-lis symbolizes French culture. It can also be seen as representative of French Canadians who form a sizable population in the American Northeast.

Settlements

editCities founded

edit- Biloxi, Mississippi was founded in 1699 by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville.

- Boise, Idaho, founded in the 1820s by French fur traders, means "wooded".

- Bourbonnais, Illinois was named after French Canadian fur trader Francois Bourbonnais. The first permanent resident was French Canadian fur trader Noel LeVasseur in the 1830s.

- Chicago, Illinois is derived from a French rendering of the Native American word shikaakwa, translated as "wild onion" or "wild garlic", from the Miami-Illinois language.[89][90][91][92] The first known reference to the site of the current city of Chicago as "Checagou" was by Robert de LaSalle around 1679 in a memoir written about the time.[93] Henri Joutel, in his journal of 1688, noted that the wild garlic, called "chicagoua," grew abundantly in the area.[90]

- Coeur d'Alene, Idaho French Canadian fur traders allegedly named the local Indian tribe the Coeur d'Alene out of respect for their tough trading practices. Cœur d'alêne literally means "heart of an awl".

- Davenport, Iowa was founded by Antoine LeClaire, an interpreter for the United States Army, in 1836.

- Detroit, Michigan was founded by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in 1701, a French Royal Army captain, and was originally called Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, after the minister of marine under Louis XIV and the French word Détroit for "strait".

- Dubuque, Iowa was established as a lead mining site by Canadian Julien Dubuque in 1788.

- Duluth, Minnesota, so-named for an Anglicization of Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, modern city established by English, first founded as early French fur-trading post.

- Dupont, Colorado, Du Pont, Georgia, Dupont, Indiana, Dupont, Ohio, Dupont, Pennsylvania, Dupont, Tennessee and DuPont, Washington, were all founded by the Du Pont family or other French settlers.

- French Camp, California was the terminus of the Oregon-California Trail used by French-Canadian fur traders (including Michel Laframboise) in the 1830s and 1840s, making it one of the oldest settlements in San Joaquin County.

- Galveston, Texas, first European settlement was established in 1816 by French pirate, Louis-Michel Aury, succeeded by Jean Lafitte, until the island's raiders were evicted by the US Navy in 1821.

- Grand Forks, North Dakota, originally "Les Grandes Fourches", when it was settled in the 1740s by fur traders.

- Green Bay, Wisconsin or La Baye, was founded by Jean Nicolet in 1634. Many residents of Green Bay are direct descendants of the French Canadian inhabitants and their families.

- Juneau, Alaska was founded in 1891 and named in honor of Joseph Juneau, a gold prospector from the region of Montreal, who settled the first mining camp in the area.

- Kaskaskia, Illinois was founded in 1703 by French Jesuit missionaries and was Illinois's first capital.

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin was founded settled by French traders most notably Jacques Vieau and established as a city by Solomon Juneau.

- Mobile, Alabama was founded in 1702 by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne. It was the first capital of Louisiana.

- Natchitoches, Louisiana was founded in 1714 by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis.

- New Orleans, Louisiana was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne and named after Philippe II, Duke of Orléans.

- New Paltz, New York was founded in 1678 by French Huguenots settlers, including Louis DuBois.

- New Rochelle, New York was founded by French Huguenots and named after La Rochelle, France.

- Peoria, Illinois was first settled with the establishment of Fort Crevecoeur in 1680, ceded to British after 1763; area of downtown was once site of "La Ville de Maillet"

- Pierre, South Dakota was named after Pierre Chouteau Jr., a fur trader of French Canadian origin, who built Fort Pierre, where the capital of Pierre stands today.

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was originally surveyed in 1669 by Robert de La Salle and was a post of French and Dutch fur traders, prior to the construction of Fort Duquesne and modern founding by the English.

- Poteau, Oklahoma was founded by French traders

- Portage Des Sioux was founded in 1799 by Zenon Trudeau and François Saucier.

- Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin was established in 1685 by Nicholas Perrot as a fur trading post.

- Prairie du Rocher, Illinois was founded in 1722 by Sister Thérèse Langlois, four years after Fort de Chartres was built by Pierre Dugué de Boisbriand.

- Saint Charles, Missouri was founded by Louis Blanchette, a French Canadian, in 1769.

- Saint Louis, Missouri was founded by a French trader, Pierre Laclède, and his stepson, a trader from Louisiana, René Auguste Chouteau in 1764.

- Sainte Genevieve, Missouri was founded in 1735 by habitants.

- Saint Ignace, Michigan was founded by father Jacques Marquette in 1671.

- St. Joseph, Missouri was founded by Joseph Robidoux c. 1826.

- Saint Paul, Minnesota was established in 1838 by Pierre Parrant and settled by French Canadians. In 1841, it was named Saint-Paul by Father Lucien Galtier in honor of Paul the Apostle.

- Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan was founded in 1668 by fathers Jacques Marquette and Claude Dablon.

- Vincennes, Indiana was established in 1732 by François-Marie Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes and rallied to the cause of the American revolution with Father Pierre Gibault.

States founded

edit- Arkansas – named by French explorers from the corrupted Indian word meaning "south wind". Arkansas Post was its first French establishment in 1686 by Henri de Tonti.

- Illinois – French for the land of the Illini, a Native American tribe. Also named from the Pays des Illinois which had a substantial population at the time of New France. French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Illinois River in 1673. In 1680, other French explorers constructed a fort at the site of present-day Peoria, and in 1682, a fort atop Starved Rock in today's Starved Rock State Park. French Canadians came south to settle particularly along the Mississippi River, and Illinois was part of the French empire of La Louisiane until 1763, when it passed to the British with their defeat of France in the Seven Years' War.

- Indiana – In 1679 the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle was the first European to cross into Indiana after reaching present-day South Bend at the Saint Joseph River.[94] French-Canadian fur traders soon arrived, bringing blankets, jewelry, tools, whiskey and weapons to trade for skins with the Native Americans. By 1702, Sieur Juchereau established the first trading post near Vincennes. In 1715, Sieur de Vincennes built Fort Miami at Kekionga, now Fort Wayne. In 1717, another Canadian, Picote de Beletre, built Fort Ouiatenon on the Wabash River. In 1732, Sieur de Vincennes built a second fur trading post at Vincennes. French Canadian settlers, who had left the earlier post because of hostilities, returned in larger numbers.

- Louisiana – from the French Louisiane, in honor of King Louis XIV of France. Named by Cavelier de La Salle who founded Louisiana and died in Texas. Many Acadians migrated to Louisiana and are today known as Cajuns.

- Maine – Two Jesuit missions were established by the French: one on Penobscot Bay in 1609, and the other on Mount Desert Island in 1613. The same year, Castine was established by Claude de La Tour. In 1625, Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour erected Fort Pentagouet to protect Castine.

- Michigan – French transcription of Ojibwe word Mishii'igan (syncopated as Mishiigan) which means "great lake". The French forts of Fort Saint-Joseph and Fort Michilimackinac, as well as the French establishments of Detroit and Saint Ignace were located in the area of Michigan which was part of New France.

- Minnesota – The first Europeans in the area were French fur traders who arrived in the 17th century. Explorers such as Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, Father Louis Hennepin, and Joseph Nicollet, among others, mapped out the state.

- Missouri – The first European settlers were mostly ethnic French Canadians, who created their first settlement in Missouri at present-day Ste. Genevieve, about an hour south of St. Louis. They had migrated about 1750 from the Illinois Country. St. Louis was founded soon after by French from New Orleans in 1764.

- Vermont – comes from a contraction of French words, Vert, green, and mont, mount, mountain. It was named by the French explorer Samuel de Champlain. French seigneuries were subdivided along Lake Champlain at the time of New France, which was later given to the British colonies by the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

- Wisconsin – named after the Meskousing River. This spelling was later corrupted from the local Native American language to "Ouisconsin" by French explorers, and over time this version became the French name both for the Wisconsin River and for the surrounding lands. La Baye was Wisconsin's main community at the time of New France. English speakers anglicized the spelling to its modern form when they began to arrive in greater numbers during the early 19th century.[95]

Historiography

editRichard (2002) examines the major trends in the historiography regarding the Franco-Americans who came to New England in 1860–1930. He identifies three categories of scholars: survivalists, who emphasized the common destiny of Franco-Americans and celebrated their survival; regionalists and social historians, who aimed to uncover the diversity of the Franco-American past in distinctive communities across New England; and pragmatists, who argued that the forces of acculturation were too strong for the Franco-American community to overcome. The 'pragmatists versus survivalists' debate over the fate of the Franco-American community may be the ultimate weakness of Franco-American historiography. Such teleological stances have impeded the progress of research by funneling scholarly energies in limited directions while many other avenues, for example, Franco-American politics, arts, and ties to Quebec, remain insufficiently explored.[96]

While a considerable number of pioneers of Franco-American history left the field or came to the end of their careers in the late 1990s, other scholars have moved the lines of debate in new directions in the last fifteen years. The "Franco" communities of New England have received less sustained scholarly attention in this period, but important work has no less appeared as historians have sought to assert the relevance of the French-Canadian diaspora to the larger narratives of American immigration, labor and religious history.

Scholars have worked to expand the transnational perspective developed by Robert G. LeBlanc during the 1980s and 1990s.[97] Yukari Takai has studied the impact of recurrent cross-border migration on family formation and gender roles among Franco-Americans.[98] Florence Mae Waldron has expanded on older work by Tamara Hareven and Randolph Langenbach in her study of Franco-American women's work within prevalent American gender norms.[99] Waldron's innovative work on the national aspirations and agency of women religious in New England also merits mention.[100] Historians have pushed the lines of inquiry on Franco-Americans of New England in other directions as well. Recent studies have introduced a comparative perspective, considered the surprisingly understudied 1920s and 1930s, and reconsidered old debates on assimilation and religious conflict in light of new sources.[101][102][103]

At the same time, there has been rapidly expanding research on the French presence in the middle and western part of the continent (the American Midwest, the Pacific coast, and the Great Lakes region) in the century following the collapse of New France.[104][105][106][107]

Notable people

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ This map does not display data of people identifying solely as Acadian/Cajun, Creole, French-Canadian, Haitian, Métis or Québécois alone, due to the difficulty of determining overlap for multiple-ancestry or ethnicity responses. Many identified with "French" Census responses in the United States and Canada will have some overlap with "French – French-Canadian" and "French – Cajun", "Haitian – French" and other responses.

Citations

edit- ^ "IPUMS USA". University of Minnesota. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "French Americans – Dictionary definition of French Americans | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ "Franco-American Alliance | French-United States history [1778]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ Barkan, Elliott Robert (January 17, 2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration [4 volumes]: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842203.

- ^ "Table B04006 - People Reporting Ancestry - 2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (2003). "Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "LANGUAGE SPOKEN AT HOME BY ABILITY TO SPEAK ENGLISH FOR THE POPULATION 5 YEARS AND OVER : Universe: Population 5 years and over : 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Shin, Hyon B.; Bruno, Rosalind (October 2003). "Language Use and English-speaking Ability: 2000" (PDF). 2000 U.S. Census. U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Ryan, Camille (2013). "Language Use in the United States: 2011 – American Community Survey Reports" (PDF). U.S. Census. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Maurault, Olivier (November 1950). The French of Canada and New England. New York: The Newcomen Society of England in North America.

- ^ "A Brief Outline of the History of New Netherland". Coin and Currency Collections. University of Notre Dame Libraries. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ a b LeFevre, Ralph (July 1921). "The Huguenots - The First Settlers in the Province of New York". The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association. 2 (3): 177–185. JSTOR 43564497. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ US census 2010

- ^ Helen Bush Caver and Mary T. Williams, "Creoles", Multicultural America, Countries and Their Cultures Website, accessed February 3, 2009

- ^ Ingersoll, Charles Jared. History of the second war between the United States of America and Great Britain: declared by act of Congress, the 18th of June, 1812, and concluded by peace, the 15th of February, 1815 Vol.2, Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1852, pp. 69ff.

- ^ 1.6 million Americans over the age of five speak the language at home; Language Use and English-Speaking Ability, fig. 3 www.census.gov (PDF)

- ^ "Haitian Immigration: 18th & 19th Centuries - The Black Republic and Louisiana". In Motion: African American Migration Experience. New York Public Library. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. p. 163. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ Higonnet, Patrice Louis René (1980). "French". In Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar (eds.). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Harvard University Press. p. 382. ISBN 0674375122. OCLC 1038430174.

- ^ Kurt Gingrich, "'That Will Make Carolina Powerful and Flourishing': Scots and Huguenots In Carolina in the 1680s", South Carolina Historical Magazine, Jan–June 2009, Vol. 110 Issue 1/2, pp 6–34,

- ^ Bertrand Van Ruymbeke, New Babylon to Eden: The Huguenots and Their Migration to Colonial South Carolina. U. of South Carolina Press, 2006.

- ^ David Lambert, The Protestant International and the Huguenot Migration to Virginia (2009)

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (2019). "Promises to Keep: French Canadians as Revolutionaries and Refugees, 1775-1800". Journal of Early American History. 9 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1163/18770703-00901004. S2CID 159066318.

- ^ Eric Jay Dolin, Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America (W.W. Norton, 2010) pp 61–132

- ^ Ekberg, Carl J. (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country. University of Illinois Press. pp. 31–100. ISBN 0-252-06924-2.

- ^ Clarence Walworth Alvord, "Father Pierre Gibault and the Submission of Post Vincennes, 1778", American Historical Review Vol. 14, No. 3 (Apr. 1909), pp. 544–557, JSTOR 1836446.

- ^ a b Mark Paul Richard, "From 'Canadien' to American: The Acculturation of French-Canadian Descendants in Lewiston, Maine, 1860 to the Present", PhD dissertation Duke U. 2002; Dissertation Abstracts International, 2002 62(10): 3540-A. DA3031009, 583p.

- ^ Waldron, Florencemae (2005), "The Battle Over Female (In)Dependence: Women In New England Québécois Migrant Communities, 1870–1930", Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 26 (2): 158–205, doi:10.1353/fro.2005.0032, S2CID 161455771

- ^ Waldron, Florencemae (2005), "'I've Never Dreamed It Was Necessary To 'Marry!': Women And Work In New England French Canadian Communities, 1870–1930", Journal of American Ethnic History, 24 (2): 34–64, doi:10.2307/27501562, JSTOR 27501562, S2CID 254493034[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hudson, Susan (2001–2002), "Les Sœurs Grises of Lewiston, Maine 1878–1908: An Ethnic Religious Feminist Expression", Maine History, 40 (4): 309–332

- ^ Richard, Mark Paul (2002). "The Ethnicity of Clerical Leadership: The Dominicans in Francophone Lewiston, Maine, 1881–1986". Quebec Studies. 33: 83–101. doi:10.3828/qs.33.1.83.

- ^ Potvin, Raymond H. (2003), "The Franco-American Parishes of New England: Past, Present and Future", American Catholic Studies, 114 (2): 55–67

- ^ Stewart, Alice R. (1987), "The Franco-Americans of Maine: A Historiographical Essay", Maine Historical Society Quarterly, 26 (3): 160–179

- ^ "French Towns in the United States; A Study of the Relative Strength of the French-Speaking Population in Our Large Cities". The American Leader. Vol. IV, no. 11. New York: American Association of Foreign Language Newspapers, Inc. December 11, 1913. pp. 672–674.

- ^ "Ready to Dedicate Gatineau Shaft at Southbridge Today". The Boston Globe. Boston. September 2, 1929. p. 5.

The memorial erected to State. Representative Felix Gatineau of Southbrldge, founder of L'Union St John the Baptist in America, the largest French Catholic fraternal organization in the United States, will be dedicated tomorrow. Labor Day and a parade in which 3000 persons will participate, will be a feature.

- ^ Richard, Mark Paul (1998), "From Franco-American to American: The Case of Sainte-Famille, An Assimilating Parish of Lewiston, Maine", Histoire Sociale: Social History, 31 (61): 71–93

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick. "Histoire des Franco-Américains: nouvelle utilité, nouvelle efflorescence?". HistoireEngagée.ca. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (April 25, 2021). "Le Droit". Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Vermette, David (2022). "The Question of a Franco-American Revival". In Stein-Smith, Kathleen; Jaumont, Fabrice (eds.). French All around Us – French language and Francophone Culture in the United States. New York City: TBR Books. pp. 205–215.

- ^ Murphy, Megan (March 15, 2022). "New Hampshire PoutineFest to Return this October". WOKQ 97.5. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ "New England Franco Route GeoTour". Geocaching. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Collins, Steve (May 29, 2022). "Lewiston's Lessard-Bissonnette to be honored with historical marker". Lewiston Sun-Journal. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ McKone, Tom (June 22, 2022). "Abby Paige and "Les Filles du Quoi?" Shine at Lost Nation Theater". The Bridge. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Carrier, Léa (September 17, 2022). "La francophonie nord-américaine en vedette dans un cours à Harvard". La Presse. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (August 13, 2017). "Why Was the Quebec Flag Flown at the Statehouse in Connecticut?". History News Network. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ St. Pierre, Timothy (2020). "Acknowledging and Confronting Racism in Franco Communities". Le Forum. 42 (3): 10, 49.

- ^ Paige, Abby (2021). "Beyond Whiteness: Imagining a Franco-American Future". Le Forum. 43 (1): 3, 7–8.

- ^ Currie, Ron (November 2, 2018). "Paul LePage and I Feel the Same Way About the Poor". Down East. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Doty, C. Stewart (1993), "Rudy Vallee: Franco-American and Man from Maine", Maine Historical Society Quarterly, 33 (1): 2–19

- ^ Foucrier, Annick (2012). "The French in Gold Rush San Francisco and spiritual kinship". Spiritual Kinship in Europe, 1500–1900. pp. 275–291. doi:10.1057/9780230362703_11. ISBN 978-1-349-34856-5.

- ^ a b Hiding in plain sight - the French of San Francisco, 30 November 2015, KALW

- ^ Sauvy, Alfred. "Assessment of French Immigration Needs". caccl-positas.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ Sessums, Martha. Paris of the Pacific: Celebrating San Francisco’s Founding French Community, France Today, 28 April 2015.

- ^ Franson, Paul. French influence in California/Pacific Northwest’s wine business, French Consulate of San Francisco, April 2018.

- ^ Vasilyuk, Sasha.French companies' transplants grow in Bay Area, SFGATE, 20 March 2010.

- ^ Canada, French Canadians and Franco-Americans in the Civil War Era (1861–1865) D.-C. Bélanger, Montreal, Quebec, June 24, 2001

- ^ Walker, David (1962), "The Presidential Politics of the Franco-Americans", Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 28 (3): 353–363, doi:10.2307/139667, JSTOR 139667

- ^ Petrin, Ronald A. (1990). French Canadians in Massachusetts Politics, 1885-1915: Ethnicity and Political Pragmatism. Philadelphia: Balch Institute Press.

- ^ Madeleine Giguère (2007). Madore, Nelson; Rodrigue, Barry (eds.). Voyages : A Maine Franco-American Reader. Gardiner: Tilbury House. pp. 474–483.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (2021). "Tout nous serait possible": Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, 1874-1945. Quebec City: Presses de l'Université Laval.

- ^ Weil, François (1990), "Les Franco-Americains et la France" (PDF), Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, 77 (3): 21–34, doi:10.3406/outre.1990.2812

- ^ Edmonton Sun, April 21, 2009

- ^ American Council of Learned Societies. Committee on Linguistic and National Stocks in the Population of the United States (1932). Report of the Committee on Linguistic and National Stocks in the Population of the United States. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1086749050.

- ^ a b "French in the US". netcapricorn.com. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Fohlen, Claude (1990). "Perspectives historiques sur l'immigration française aux États-Unis" (PDF). Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales. 6 (1): 29–43. doi:10.3406/remi.1990.1225. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Source of the data: US Census Bureau, « Population Group: French (except Basque) » Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, recensement de 2010 (9,529,969 habitants)

- ^ US Census Bureau, « Population Group: French Canadian » Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, recensement de 2010 (2,265,648 habitants)

- ^ a b Source of the data: Histoire des Acadiens, Bona Arsenault, Éditions Leméac, Ottawa, 1978

- ^ Rouse, Parke (July 7, 1996). "Huguenots sought freedom". Daily Press. Newport News, Va. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019.

- ^ Spiegel, Taru (September 30, 2019). "Teaching French at Harvard and L'Abeille Françoise". 4 Corners of the World; International Collections. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019.

- ^ Auto racer Louis Chevrolet was a Swiss Catholic. He made automobiles bearing his name before selling out in 1915; General Motors purchased the brand in 1917.

- ^ Rumilly, Robert (1958). Histoire des Franco-Américains. Montreal: Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste d'Amérique.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (2016). "A Church of Two Steeples: Catholicism, Labor, and Ethnicity in Industrial New England, 1869–1890". Catholic Historical Review. 102 (4): 746–770. doi:10.1353/cat.2016.0206. S2CID 159662405.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (2017). "Americanization by Catholic Means: French Canadian Nationalism and Transnationalism, 1889-1901". Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 16 (3): 284–301. doi:10.1017/S1537781416000384. S2CID 164667346.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (2018). "À l'assaut de la corporation sole : autonomie institutionnelle et financière chez les Franco-Américains du Maine, 1900-1917". Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française. 72 (1): 31–51. doi:10.7202/1051145ar.

- ^ Woonsocket Rhode Island, A Centennial History, 1888-2000 The Millennium Edition pg. 87

- ^ Richard S. Sorrell, "Sentinelle Affair (1924–1929): Religion and Militant Survivance in Woonsocket, Rhode Island," Rhode Island History, Aug 1977, Vol. 36 Issue 3, pp 67–79

- ^ Green, Constance McLaughlin (1957). American Cities in the Growth of the Nation. New York: J. De Graff. p. 88. OCLC 786169259.

- ^ Hillary Kaell, "'Marie-Rose, Stigmatisée de Woonsocket': The Construction of a Franco-American Saint Cult, 1930–1955", Historical Studies, 2007, Vol. 73, pp 7–26

- ^ "Rechercher un établissement". Agency for French Education Abroad. Retrieved on October 24, 2015.

- ^ Melvin Ember; et al. (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Springer. p. 528. ISBN 9780306483219.

- ^ Ronald Arthur Petrin (1990). French Canadians in Massachusetts Politics, 1885–1915: Ethnicity and Political Pragmatism. Balch Institute Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780944190074.

- ^ Claire Quintal, ed., Steeples and Smokestacks. A Collection of essays on The Franco-American Experience in New England (1996) pp 618-9

- ^ Quintal p 614

- ^ Quintal p 618

- ^ Richard, "American Perspectives on La fièvre aux États-Unis, 1860–1930," p 105, quote on p 109

- ^ The French-Canadian heritage in New England ([International version] ed.). University Press of New England. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0-7735-0537-7.

- ^ "The Robert Couturier Collection - Audio-Visual Materials". Franco-American Collection | University of Southern Maine. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019.

- ^ For a historical account of interest, see the section entitled "Origin of the word Chicago" in Andreas, Alfred Theodore, History of Chicago, A. T. Andreas, Chicago (1884) pp 37–38.

- ^ a b Swenson, John F. (Winter 1991). "Chicagoua/Chicago: The origin, meaning, and etymology of a place name". Illinois Historical Journal. 84 (4): 235–248. ISSN 0748-8149. OCLC 25174749.

- ^ McCafferty, Michael (December 21, 2001). ""Chicago" Etymology". The LINGUIST List. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ McCafferty, Michael (Summer 2003). "A Fresh Look at the Place Name Chicago". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 96 (2). Illinois State Historical Society. ISSN 1522-1067. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ Quaife, Milton M. Checagou, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press., 1933).

- ^ Allison, p. 17.

- ^ "Origin of State Names". infoplease.com. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Richard, Sacha (2002). "American Perspectives on La fièvre aux Etats-Unis, 1860–1930: A Historiographical Analysis of Recent Writings on the Franco-Americans in New England". Canadian Review of American Studies. 32 (1): 105–132. doi:10.3138/CRAS-s032-01-05. S2CID 161389855.

- ^ Pinette, Susan (2002). "Franco-American Studies in the Footsteps of Robert G. LeBlanc". Quebec Studies. 33: 9–14. doi:10.3828/qs.33.1.9.

- ^ Takai, Yukari (2008). Gendered Passages: French-Canadian Migration to Lowell, Massachusetts, 1900–1920. New York City: Peter Lang.

- ^ Waldron, Florence Mae (2005). "'I've Never Dreamed It Was Necessary to Marry!': Women and Work in New England French Canadian Communities, 1870–1930". Journal of American Ethnic History. 24 (2): 34–64. doi:10.2307/27501562. JSTOR 27501562. S2CID 254493034.

- ^ Waldron, Florence Mae (2009). "Re-evaluating the Role of 'National' Identities in the American Catholic Church at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: The Case of Les Petites Franciscaines de Marie (PFM)". Catholic Historical Review. 95 (3): 515–545. doi:10.1353/cat.0.0451. S2CID 143533518.

- ^ Ramirez, Bruno (2015). "Globalizing Migration Histories? Learning from Two Case Studies". Journal of American Ethnic History. 34 (4): 17–27. doi:10.5406/jamerethnhist.34.4.0017.

- ^ Richard, Mark Paul (2016). "'Sunk into Poverty and Despair: Franco-American Clergy Letters to FDR during the Great Depression". Quebec Studies. 61: 39–52. doi:10.3828/qs.2016.4.

- ^ Lacroix, Patrick (2016). "A Church of Two Steeples: Catholicism, Labor, and Ethnicity in Industrial New England, 1869-1890". Catholic Historical Review. 102 (4): 746–770. doi:10.1353/cat.2016.0206. S2CID 159662405.

- ^ Gitlin, Jay (2009). The Bourgeois Frontier: French Towns, French Traders, and American Expansion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Englebert, Robert; Teasdale, Guillaume, eds. (2013). French and Indians in the Heart of America, 1630–1815. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- ^ Barman, Jean (2014). French Canadians, Furs, and Indigenous Women in the Making of the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- ^ Teasdale, Guillaume; Villerbu, Tangi, eds. (2015). Une Amérique française, 1760–1860: Dynamiques du corridor créole. Paris: Les Indes savantes.

Further reading

edit- Albert, Renaud S; Martin, Andre; Giguere, Madeleine; Allain, Mathe; Brasseaux, Carl A (May 1979). A Franco-American Overview (PDF). Vol. I–V. Cambridge, Mass.: National Assessment and Dissemination Center, Lesley College; US Department of Education – via Education Resources Information Center (ERIC).

- Baird, Charles Washington (1885). History of the Huguenot Emigration to America, Dodd, Mead & Company, (online: Volume I)

- Blumenthal, Henry. (1975) American and French Culture, 1800–1900: Interchanges in Art." Science, Literature, and Society

- Bond, Bradley G. (2005). French Colonial Louisiana and the Atlantic World, LSU Press, 322 pages ISBN 0-8071-3035-4 (online excerpt)

- Butler, Jon. (1992) The Huguenots in America: A Refugee People in New World Society (Harvard UP)

- Brasseaux, Carl A. (1987). The Founding of New Acadia. The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana, 1765–1803, LSU Press, 229 pages ISBN 0-8071-2099-5

- Childs, Frances Sergeant. (1940)French Refugee Life in the United States 1790–1800: An American Chapter of the French Revolution online

- Cote, Rhea Robbins. (1997) Wednesday's Child, Rheta Press, 96 pages ISBN 978-0-9668536-4-3

- Cote, Rhea Robbins. (2013) 'down the Plains' , Rheta Press, 226 pages ISBN 978-0-615-84110-6

- Ekberg, Carl J. (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country. The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times, University of Illinois Press, 376 pages ISBN 0-252-06924-2 (online excerpt)

- Higonnet, Patrice Louis René. "French" in Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar, eds. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674375122, (1980) pp 379–88.

- Jones, Howard Mumford. (1927) America and French Culture, 1750–1848 online free to borrow

- Lagarde, François. (2003). The French in Texas. History, Migration, Culture (U of Texas Press, 330 pages ISBN 0-292-70528-X (online excerpt)

- Laflamme, J.L.K., David E. Lavigne and J. Arthur Favreau. (1908) Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "French Catholics in the United States". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Lamarre, Jean. Les Canadiens français du Michigan: leur contribution dans le développement de la vallée de la Saginaw et de la péninsule de Keweenaw, 1840-1914 (Les éditions du Septentrion, 2000). online

- Louder, Dean R., and Eric Waddell, eds. (1993). French America. Mobility, Identity, and Minority Experience Across the Continent, Louisiana State University Press, 371 pages ISBN 0-8071-1669-6

- Lindenfeld, Jacqueline. (2002). The French in the United States. An Ethnographic Study, Greenwood Publishing Group, 184 pages ISBN 0-89789-903-2 (online excerpt)

- Monnier, Alain. "Franco-Americains et Francophones aux Etats-Unis" ("Franco-Americans and French Speakers in the United States). Population 1987 42(3): 527–542. Census study.

- Pritchard, James S. (2004). In Search of Empire. The French in the Americas, 1670–1730, Cambridge University Press, 484 pages ISBN 0-521-82742-6 (online excerpt)

- Rumily, Robert. (1958) Histoire des Franco Americains. a standard history

- Valdman, Albert. (1997). French and Creole in Louisiana, Springer, 372 pages ISBN 0-306-45464-5 (online excerpt)

- Weil, François. "Les Franco-Americains et la France' ("Franco-Americans and France") Revue Francaise d'Histoire d'Outre-Mer 1990 77(3): 21–34

External links

edit- Extensive studies, Documents, Statistics and Resources of Franco American History

- Franco American Women's Institute

- Institut français

- Dave Martucci, Franco-American flags, in Flags of the World

- Vivre en Orange County – French Community in Orange County, California

- Bonjour L.A. !- Bonjour L.A. ! Los Angeles with a French touch

- Council for the Development of French in Louisiana – a state agency.

- Oral History of French Canadians in Franklin County, New York and of a small sawmill and logging community in the Northern New York State populated by French Canadians