This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

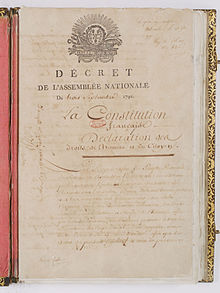

The French Constitution of 1791 (French: Constitution française du 3 septembre 1791) was the first written constitution in France, created after the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime. One of the basic precepts of the French Revolution was adopting constitutionality and establishing popular sovereignty.

| French Constitution of 1791 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Original title | Constitution française du 3 septembre 1791 |

| Jurisdiction | France |

| Created | 3 September 1791 |

| Date effective | 14 September 1791 |

| System | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Head of state | Monarch |

| Chambers | Unicameral (Legislative Assembly) |

| Author(s) | National Constituent Assembly |

Drafting process

editEarly efforts

editFollowing the Tennis Court Oath, the National Assembly began the process of drafting a constitution as its primary objective. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted on 26 August 1789 eventually became the preamble of the constitution adopted on 3 September 1791.[1] The Declaration offered sweeping generalizations about rights, liberty, and sovereignty.[2]

A twelve-member Constitutional Committee was convened on 14 July 1789 (coincidentally the day of the Storming of the Bastille). Its task was to do much of the drafting of the articles of the constitution. It included originally two members from the First Estate (Champion de Cicé, Archbishop of Bordeaux and Talleyrand, Bishop of Autun); two from the Second (the comte de Clermont-Tonnerre and the marquis de Lally-Tollendal); and four from the Third (Jean Joseph Mounier, Abbé Sieyès, Nicholas Bergasse, and Isaac René Guy le Chapelier).

Many proposals for redefining the French state were floated, particularly in the days after the remarkable sessions of 4–5 August 1789 and the abolition of feudalism. For instance, the Marquis de Lafayette proposed a combination of the American and British systems, introducing a bicameral parliament, with the king having the suspensive veto power over the legislature, modeled to the authority then recently vested in the President of the United States.

The main controversies early on surrounded the issues of what level of power to be granted to the king of France (i.e.: veto, suspensive or absolute) and what form would the legislature take (i.e.: unicameral or bicameral). The Constitutional Committee proposed a bicameral legislature, but the motion was defeated 10 September 1789 (849–89) in favor of one house; the next day, they proposed an absolute veto, but were again defeated (673–325) in favor of a suspensive veto, which could be over-ridden by three consecutive legislatures.

New Constitutional Committee

editA second Constitutional Committee quickly replaced it, and included Talleyrand, Abbé Sieyès, and Le Chapelier from the original group, as well as new members Gui-Jean-Baptiste Target, Jacques Guillaume Thouret, Jean-Nicolas Démeunier, François Denis Tronchet, and Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne, all of the Third Estate. As Simon Schama has pointed out, many of the members of the Constitutional Committee were themselves members of nobility, many of whom would later face execution.[3]

Their greatest controversy faced by this new committee surrounded the issue of citizenship. Would every subject of the French Crown be given equal rights, as the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen seemed to promise, or would there be some restrictions? The October Days (5–6 October) intervened and rendered the question much more complicated. In the end, a distinction was held between active citizens (over the age of 25, paid direct taxes equal to three days' labor) which had political rights, and passive citizens, who had only civil rights. This conclusion was intolerable to such radical deputies as Maximilien Robespierre, and thereafter they never could be reconciled to the Constitution of 1791.

Committee of Revisions

editA second body, the Committee of Revisions, was struck September 1790, and included Antoine Barnave, Adrien Duport, and Charles de Lameth. Because the National Assembly was both a legislature and a constitutional convention, it was not always clear when its decrees were constitutional articles or mere statutes. It was the job of this committee to sort it out. The committee became very important in the days after the Champs de Mars Massacre, when a wave of revulsion against popular movements swept France and resulted in a renewed effort to preserve powers for the Crown. The result is the rise of the Feuillants, a new political faction led by Barnave, who used his position on the committee to preserve a number of powers for the Crown, such as the nomination of ambassadors, military leaders, and ministers.

Results

editAfter very long negotiations, the constitution was reluctantly accepted by King Louis XVI in September 1791. Redefining the organization of the French government, citizenship and the limits to the powers of government, the National Assembly set out to represent the interests of the general will. It abolished many “institutions which were injurious to liberty and equality of rights”. The National Assembly asserted its legal presence in French government by establishing its permanence in the Constitution and forming a system for recurring elections. The Assembly's belief in a sovereign nation and in equal representation can be seen in the constitutional separation of powers. The National Assembly was the legislative body, the king and royal ministers made up the executive branch and the judiciary was independent of the other two branches. On a local level, the previous feudal geographic divisions were formally abolished, and the territory of the French state was divided into several administrative units, Departments (Départements), but with the principle of centralism.

Evaluation

editThe Assembly, as constitution-framers, were afraid that if only representatives governed France, it was likely to be ruled by the representatives' self-interest; therefore, the king was allowed a suspensive veto to balance out the interests of the people. By the same token, representative democracy weakened the king’s executive authority.

The constitution was not egalitarian by today's standards. It distinguished between the propertied active citizens and the poorer passive citizens. Women lacked rights to liberties such as education, freedom to speak, write, print and worship.[citation needed]

Keith M. Baker writes in his essay “Constitution” that the National Assembly threaded between two options when drafting the Constitution: they could modify the existing, unwritten constitution centered on the three estates of the Estates General or they could start over and rewrite it completely. The National Assembly wanted to reorganize social structure and legalize itself: while born of the Estates General of 1789, it had abolished the tricameral structure of that body.

With the onset of war and the threat of the revolution's collapse, radical Jacobin and ultimately republican conceptions grew enormously in popularity, increasing the influence of Robespierre, Danton, Marat and the Paris Commune. When the King used his veto powers to protect non-juring priests and refused to raise militias in defense of the revolutionary government, the constitutional monarchy proved unworkable and was effectively ended by the 10 August insurrection. A National Convention was called, electing Robespierre as its first deputy; it was the first assembly in France elected by universal male suffrage. The convention declared France a republic on 22 September 1792.[4]

Timeline of French constitutions

editSee also

edit- De Tracy's longest speech to the Constituent Assembly was on the situation in Saint-Domingue, which was repeatedly interrupted by applause and published in a separate pamphlet.[5]

- French Revolution

- Kingdom of France (1791–92)

- United States Constitution

- Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth 1791 Constitution

References

edit- ^ The Constitution of 1791

- ^ Popiel, Jennifer; Carnes, Mark; Kates, Gary (2015). Rousseau, Burke, and Revolution in France, 1791 (2nd ed.). W.W. Norton & Company. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-393-93888-3.

- ^ Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, NY: Penguin Books p. 478 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Pertue, M. "Constitution de 1791," in Soboul, Ed., "Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution francaise," pp. 282–283. Quadrige/PUF, Paris: 2005. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Opinion de M. de Tracy sur les affaires de Saint-Domingue, en septembre 1791. Paris: Laillet, s. a. (1791)

External links

edit- "Constitution de 1791". Conseil constitutionnel (in French). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Constitution of 1791, University of California, Santa Cruz (in English) (partial only)

- Constitution of 1791: complete text Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine