Poncelet was a French Navy Redoutable-class submarine of the M6 series commissioned in 1932. She participated in World War II, first on the side of the Allies from 1939 to June 1940, then served in the navy of Vichy France. She was scuttled during the Battle of Gabon in November 1940. Her commanding officer at the time of her loss,Capitaine de corvette (Corvette Captain) Bertrand de Saussine du Pont de Gault, is regarded as a national naval hero in France for sacrificing his life to scuttle her and ensure that she did not fall into enemy hands.

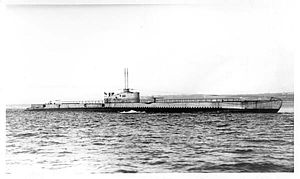

Poncelet′s sister ship Ajax in 1930.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Poncelet |

| Namesake | Jean-Victor Poncelet (1788–1867), French engineer and mathematician |

| Operator | French Navy |

| Builder | Arsenal de Lorient, Lorient, France |

| Laid down | 3 March 1927 |

| Launched | 10 April 1929 |

| Commissioned | 1 September 1932 |

| Homeport | Brest, France |

| Fate | Scuttled 7 November 1940 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Redoutable-class submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 92.3 m (302 ft 10 in) |

| Beam | 8.1 m (26 ft 7 in)[1] |

| Draft | 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) (surfaced) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Range |

|

| Test depth | 80 m (262 ft) |

| Complement | |

| Armament |

|

Characteristics

editPoncelet was part of a fairly homogeneous series of 31 deep-sea patrol submarines also called "1,500-tonners" because of their displacement.[2] All entered service between 1931 and 1939.

The Redoutable-class submarines were 92.3 metres (302 ft 10 in) long and 8.1 metres (26 ft 7 in) in beam and had a draft of 4.4 metres (14 ft 5 in). They could dive to a depth of 80 metres (262 ft). They displaced 1,572 tonnes (1,547 long tons) on the surface and 2,082 tonnes (2,049 long tons) underwater. Propelled on the surface by two diesel engines producing a combined 6,000 horsepower (4,474 kW), they had a maximum speed of 18.6 knots (34.4 km/h; 21.4 mph). When submerged, their two electric motors produced a combined 2,250 horsepower (1,678 kW) and allowed them to reach 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Also called “deep-cruising submarines”, their range on the surface was 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Underwater, they could travel 100 nautical miles (190 km; 120 mi) at 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph).

Construction and commissioning

editPoncelet was authorized under the 1925 naval program.[3] She was laid down at Arsenal de Lorient in Lorient, France, on 20 August 1925[3] with the hull number Q141. Work was halted on 3 March 1927,[3] but later resumed, and she was launched on 10 April 1929[3] at the same time as her sister ship Henri Poincaré. Poncelet completed fitting out for sea trials on 15 October 1930,[3] passed her official acceptance trials on 20 February 1931,[3] and completed her final fitting-out on 5 February 1932.[3] She was declared complete on 10 February 1932[3] and was commissioned on 1 September 1932.[3]

Service history

edit1932–1939

editOn 28 October 1937, one of the sailors in Poncelet′s engineering department suffered an injury.[3]

World War II

editFrench Navy

editAt the start of World War II in September 1939, Poncelet was assigned to the 6th Submarine Division in the 4th Submarine Squadron in the 1st Squadron, based in Brest, France.[3][4] Her sister ships Ajax, Archimède, and Persée made up the rest of the division.[3][4]

On 20 September 1939, Poncelet and Persée departed Brest to patrol in the Atlantic Ocean to the north and south of the Azores, where seven German merchant ships — which the Allies suspected of serving as supply ships for German U-boats — had taken refuge at the start of the war.[3][5] On 23[6] or 28[3] September 1939 (according to different sources), Poncelet became the only French submarine whose crew boarded an enemy merchant ship during World War II when she captured the German cargo ship Chemnitz. Chemnitz — making a voyage from Durban, South Africa, to Hamburg, Germany, with a cargo of 2,500 tonnes (2,460 long tons; 2,760 short tons) of lead ore, 2,000 tonnes (1,970 long tons; 2,200 short tons) of lead, 1,000 tonnes (980 long tons; 1,100 short tons) of wheat, 850 tonnes (840 long tons; 940 short tons) of flour, and 500 tonnes (490 long tons; 550 short tons) of barley — had slipped out of Las Palmas on Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands in an attempt to reach Germany, but Poncelet captured her 70 nautical miles (130 km; 81 mi) south of Faial Island in the Azores and took her as a prize, sending her to Casablanca in French Morocco under the control of a prize crew.[3][6] Poncelet then proceeded to Cherbourg, France, along with Persée for a refit.[3][7]

German ground forces advanced into France on 10 May 1940, beginning the Battle of France. Poncelet departed Cherbourg, then called at Brest. Italy declared war on France on 10 June 1940 and joined the invasion. As the Germans approached Brest, Poncelet evacuated the base, getting underway at 18:30 on 18 June 1940 with the submarine tender Jules Verne and 13 other submarines,[3] including her sister ships Ajax, Casabianca, Persée, and Sfax. They arrived at Casablanca on 23 June 1940.[3][8] The Battle of France ended in France's defeat and armistices with Germany on 22 June 1940 and with Italy on 24 June, both of which went into effect on 25 June 1940.

Vichy France

editAfter France's surrender, Poncelet served in the naval forces of Vichy France. After the British Royal Navy attacked the French Navy squadron at Mers El Kébir, French Morocco, on 3 July 1940, Poncelet was assigned along with Casabianca and Sfax to defensive patrols off French Morocco, the three submarines combining to maintain a continuous offshore presence from 6 to 18 July 1940, when the submarines Amphitrite, Calypso, and Méduse relieved them.[3][9]

On 8 August 1940, the French Navy put a reorganization into effect which placed Poncelet and Persée in the 6th Submarine Division and transferred them to Dakar in Senegal.[3] On 2 September 1940, Poncelet got underway from Dakar with the aviso Bougainville and the banana boat Cap des Palmes, which was loaded with troops and supplies. Poncelet escorted Cap de Palmes as she approached Mayumba on the coast of Gabon — then a territory of French Equatorial Africa — to land the troops, but the landing was cancelled when the French discovered British forces at Mayumba.[3] Poncelet then proceeded to Port-Gentil in Gabon.[3][10] As of 26 October 1940, she remained at Port-Gentil.[3]

Battle of Gabon

editOn 7 November 1940, Free French forces began amphibious landings to capture Gabon from Vichy France,[11] resulting in the Battle of Gabon. At the time, Poncelet, which was at Port-Gentil, and Bougainville, which was at Libreville, were the only Vichy French vessels available for the defense of Gabon.[12] British forces provided cover for the landings, and at 06:30 Alpha Time on 7 November the Royal Navy heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire[11] — flagship of the British task force commander, Admiral John Cunningham[13] — launched a Supermarine Walrus biplane flying boat to search for Poncelet.[11] It returned at 07:45 Alpha Time and reported that Poncelet was anchored off Port-Gentil, 8 nautical miles (15 km; 9.2 mi) and bearing 138 degrees from Cape Lopez.[11]

Poncelet had put about a quarter[3] or a third[11] (according to different sources) of her crew ashore to reinforce the Vichy French garrison at Port-Gentil,[11] but she received orders to attack the transports carrying the Free French invasion force[12] off Libreville[3] with the crew she had on board, and she set out toward the Baie des Baleiniers.[3] She sighted the masts of the Royal Navy sloop-of-war HMS Milford,[3] which was on antisubmarine patrol to the north and northeast of Cape Lopez, and at 15:52 Alpha Time, Milford reported that Poncelet had gotten underway.[11] At 16:15, Milford reported Poncelet zigzagging on the surface on a course of 60 degrees, while Milford herself was making 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) on a course of 60 degrees.[11] At 16:19, Milford reported her own position as 00°20′S 008°50′E / 0.333°S 8.833°E and that Poncelet was 7 nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi) distant, bearing 30 degrees and still on a course of 60 degrees.[11]

Loss

editMilford was too slow to intercept Poncelet as long as Poncelet remained on the surface and undamaged, so Cunningham ordered Devonshire to launch a Walrus to attack Poncelet in the hope of either damaging her or forcing her to dive, which in either case would slow her and give Milford a chance to overtake her.[11][13] Devonshire launched the Walrus at 16:50 Alpha Time.[11] At 17:00 Alpha Time, Milford reported herself at 00°11′S 008°57′E / 0.183°S 8.950°E and that Poncelet was 6.5 nautical miles (12.0 km; 7.5 mi) distant, making 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) and steering a course of 39 degrees.[11] The Walrus straddled Poncelet with two 100-pound (45 kg) depth charges, damaging her and forcing her to submerge.[11][13]

At 17:20 Alpha Time, Milford reported that Poncelet had altered course to the west and submerged and that she was engaging Poncelet.[11] Poncelet fired a torpedo at Milford which passed under Milford without exploding.[11][14] Poncelet attempted to fire a second torpedo, but it got stuck in its tube, gave off toxic smoke into the interior of the submarine, and created a leak.[11][14] Milford depth-charged Poncelet, damaging her and forcing her to the surface, then opened gunfire on her.[3] She submerged again, but was too badly damaged to withstand the dive, and her crew faced the danger of asphyxiation from the smoke emitted by the torpedo, so Poncelet′s commanding officer, Capitaine de corvette (Corvette Captain) Bertrand de Saussine du Pont de Gault, ordered the submarine to surface and her crew to abandon ship.[3][14] Soon after engaging Poncelet, Milford reported that Poncelet had surfaced at 00°04′S 008°56′E / 0.067°S 8.933°E.[11]

The British light cruiser HMS Delhi received orders at 18:01 Alpha Time to close with Poncelet and put a prize crew aboard her.[11] At 18:05, Milford signaled that Poncelet′s engines had broken down and that she had surrendered.[11] Once certain that his crew was safe, de Saussine went back aboard Poncelet and opened her seacocks, scuttling her at 00°20′S 008°50′E / 0.333°S 8.833°E to prevent her from falling into enemy hands.[11][14] He decided to remain aboard as she sank and went down with his ship, the only member of Poncelet′s crew lost in her sinking.[3][12][14][15][16] At 18:20, Milford reported that Poncelet had been scuttled and that she was picking up survivors.[11] Although Delhi received orders to assist in the rescue, Milford brought aboard all 54 survivors — three officers and 51 enlisted men.[11]

Aftermath

editDelhi reported at 19:22 Alpha Time on 7 November 1940 that she was in company with Milford and the British auxiliary naval trawler HMS Turcoman at 00°01′N 009°03′E / 0.017°N 9.050°E and that the prisoners-of-war from Poncelet would spend the night of 7–8 November aboard Milford.[11] Devonshire rendezvoused with Milford at 05:45 Alpha Time on 8 November 1940 to receive a full report on Milford′s engagement with Poncelet.[11] Milford transferred Poncelet′s survivors to Delhi at 07:45 Alpha Time on 9 November 1940 while a Walrus from Devonshire flew over the scene to provide antisubmarine cover.[11] At 14:00 Alpha Time on 9 November, Delhi detached from the task force to refuel at Lagos, Nigeria, which she reached at around 11:30 Alpha Time on 10 November 1940.[11] She disembarked the prisoners-of-war from Poncelet at Lagos.[11]

In France, de Saussine is regarded as a national naval hero.[17] His classmate and close friend, French Navy officer and French Resistance hero Honoré d'Estienne d'Orves, who fought in the Free French Naval Forces, was deeply affected by the death of de Saussine.[18][19] Chemnitz — the merchant ship Poncelet captured in September 1939 — was renamed Saint-Bertrand in honor of de Saussine after his death.[20]

The British eventually released Poncelet′s survivors, and they arrived at Dakar on 15 March 1943.[3] As of July 2022, the wreck of Poncelet remains undiscovered.

In media

editThe end of Poncelet is recounted by the writer Jean Noli in his 1971 book Le choix: les marins français au combat ("The Choice: French Sailors in Combat").

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "FR Ajax of the French Navy – French Submarine of the Redoutable class – Allied Warships of WWII". uboat.net. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ Perchoc, Michel (2004). Pages D'histoire Navale. Éd. du Gerfaut. ISBN 978-2-914622-49-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Sous-Marins Français Disparus & Accidents: Sous-Marin Poncelet (in French) Accessed 27 August 2022

- ^ a b Huan, p. 49.

- ^ Picard, pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b Auphan & Mordal, p. 35.

- ^ Huan, p. 62.

- ^ Picard, p. 39.

- ^ Huan, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Huan, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Allied Warships: FR Poncelet, uboat.net Accessed 9 July 2022

- ^ a b c Clayton, p. 118.

- ^ a b c "Commander David Corky Corkhill obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 13 December 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Fiche biographique de Bertrand De Saussine" (in French). Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Jennings, p. 44.

- ^ Picard, p. 42.

- ^ Clayton, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Ntoma Mengome, p. 52.

- ^ Montety, p. 204.

- ^ Picard, pp.33–34.

Bibliography

edit- Clayton, Anthony (2014). Three Republics, One Navy: A Naval History of France 1870–1999. Solihull, England: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-911096-74-0.

- Fontenoy, Paul E. (2007). Submarines: An Illustrated History of Their Impact (Weapons and Warfare). Santa Barbara, California. ISBN 978-1-85367-623-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[verification needed] - Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Huan, Claude (2004). Les Sous-marins français 1918–1945 (in French). Rennes: Marines Éditions. ISBN 9782915379075.

- Jennings, Eric T. (2015). French Africa in World War II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107048485.

- Montety, Étienne de (2001). Honoré d'Estienne d'Orves: Un héros français (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-01576-3.

- Ntoma Mengome, Barthélémy (2013). La bataille de Libreville: De Gaulle contre Pétain : 50 morts (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 88. ISBN 978-2-343-01045-8..

- Picard, Claude (2006). Les Sous-marins de 1 500 tonnes (in French). Rennes: Marines Éditions. ISBN 2-915379-55-6.