Qin, known as the Former Qin and Fu Qin (苻秦) in historiography,[4] was a dynastic state of China ruled by the Fu (Pu) clan of the Di peoples during the Sixteen Kingdoms period. Founded in the wake of the Later Zhao dynasty's collapse in 351, it completed the unification of northern China in 376 during the reign of Fu Jiān (Emperor Xuanzhao), being the only state of the Sixteen Kingdoms to achieve so.[5] Its capital was Chang'an up to Fu Jiān's death in 385. The prefix "Former" is used to distinguish it from the Later Qin and Western Qin dynasties that were founded later.

Qin 秦 | |

|---|---|

| 351–394 | |

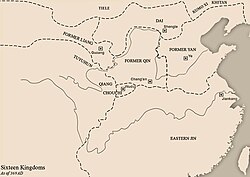

Former Qin 369 CE | |

Former Qin 376 CE | |

| Capital | Chang'an (351–385) Jinyang (385–386) Nan'an (386–394) Huangzhong (394) |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Emperor | |

• 351–355 | Fu Jiàn |

• 355–357 | Fu Sheng |

• 357–385 | Fu Jiān |

• 385–386 | Fu Pi |

• 386–394 | Fu Deng |

• 394 | Fu Chong |

| History | |

• Fu Jiàn's entry into Chang'an | 350 |

• Established | 4 March[1][2] 351 |

• Fu Jiàn's claim of imperial title | 352 |

• Fu Jiān's destruction of Former Yan | 370 |

| 383 | |

• Fu Jiān's death | 16 October 385[1][3] |

• Disestablished | 394 |

• Fu Hong's death | 405 |

| Today part of | China |

| Former Qin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 前秦 | ||||||

| |||||||

In 383, the severe defeat of the Former Qin by the Jin dynasty at the Battle of Fei River encouraged uprisings, splitting Former Qin territory into two noncontiguous pieces after the death of Fu Jiān. One remnant, at present-day Taiyuan, Shanxi was soon overwhelmed in 386 by the Xianbei under the Later Yan, Western Yan and the Dingling. The other struggled in greatly reduced territories around the border of present-day Shaanxi and Gansu until its final disintegration in 394 following years of invasions by Western Qin and Later Qin.

All rulers of Former Qin proclaimed themselves "Emperor", except for Fu Jiān who only claimed the title "Heavenly King" (Tian Wang). He was nonetheless posthumously considered an emperor by the Former Qin imperial court.

History

editBackground

editThe Fu clan was originally named Pu (蒲) and they were an influential tribe in Lüeyang Commandery under the Western Jin dynasty. During the Upheaval of the Five Barbarians, many refugees fled to them, and their chieftain, Pu Hong declared independence before submitting to the Xiongnu-led Former Zhao dynasty in the Guanzhong region. He later submitted to the Jie-led Later Zhao dynasty, which conquered Former Zhao in 329. After Shi Hu seized power in 333, Pu Hong convinced him to resettle the various Di and Qiang tribes in Guanzhong to live around the capital region in Xiangguo. Pu Hong and his family were moved to Fangtou (枋頭, in modern Hebi, Henan), where he supervised the Di tribes as the Colonel Who Protects the Di (護氐校尉) and became a favoured general of Shi Hu.

After Shi Hu's death in 349, Pu Hong played a role in instigating the Later Zhao princes' internecine struggle for the throne. He then took advantage of the confusion to lead his armies west towards Guanzhong, where he planned to establish an independent state. In accordance to a prophecy, he changed his family name to Fu (苻) and, after briefly being a vassal to the Eastern Jin dynasty, proclaimed himself King of the Three Qins. However, en route, he was assassinated by one of his generals.

Fu Hong's son and heir, Fu Jiàn, quickly quelled the rebellion and succeeded his father. Initially, he renounced his father's imperial titles and redeclared himself as a Jin vassal, but once he captured the ancient capital of Chang'an, he declared independence from Jin by claiming the title of Heavenly King of Qin.

Reign of Fu Jiàn and Fu Sheng

editFu Jiàn further elevated himself to Emperor of Qin in 352. During his reign, he expanded his state by defeating remnants of the Later Zhao and wresting for control over the Longxi region with the Former Liang. His most serious challenge was in 354, when the Eastern Jin dynasty commander, Huan Wen launched his first northern expedition against them. Fu Jiàn barely repelled him using a scorched earth strategy, and during the battle, his crown prince, Fu Chang (苻萇), was killed.

Not long after, Fu Jiàn died in 355 and was succeeded by his son Fu Sheng. Traditional historians describe Fu Sheng as a violent ruler, killing many of his high-ranking officials over trivial matters. During his reign, he forced the Former Liang into submission and killed the Qiang warlord, Yao Xiang. However, as he planned to have his cousins killed, he was overthrown in a coup in 357 led his cousin, Fu Jiān (note the different pinyin from his uncle and first ruler, Fu Jiàn).

Rise of Fu Jiān and unification of northern China

editAfter Fu Jiān ascended the throne, he changed the imperial title back to Heavenly King. Although a Di, he had a strong background in Confucian education and employed many Han Chinese officials, the most prominent being his Prime Minister, Wang Meng. With the help of Wang Meng, Fu Jiān shifted the state's initial dependence on mercantile towards agrarian policies by promoting agriculture, building irrigation facilities along with resettling the Xiongnu and Xianbei people to work on the farmlands. Imperial power was centralized by reorganizing the bureaucracy and cracking down on powerful, corrupt nobles and officials. He also emphasized education and restored many of the traditional Chinese rituals.

Fu Jiān's early reign dealt with internal revolts by his dukes and vassal warlords, but by 368, these issues had largely been dealt with. At the time, his main rivals were the Former Yan to the east, led by the Murong-Xianbei, and the Eastern Jin in the south. In 369, taking advantage of Former Yan's vulnerability, Former Qin forces led by Wang Meng launched an invasion, and by the end of 370, all of Yan was conquered. In 371, Qin conquered Chouchi, and in 373, they captured Sichuan from Jin. Qin's unification of northern China was completed in 376, when they conquered Former Liang and Dai. Fu Jiān treated his defeated enemies with leniency and allowed them to serve in his administration.

Former Qin also began receiving envoys from various states including Silla and Goguryeo. While upholding Confucianism, Fu Jiān also expressed interest in Buddhism. In 379, he welcomed the Buddhist monk, Dao'an into his court and made him a political advisor. In 382, he sent his Di general, Lü Guang on an expedition to the Western Regions while requesting that he bring him Kumārajīva, a monk from Kucha.

Battle of Fei River

editThe Eastern Jin was the last state in the way of Former Qin's unification of China. Wang Meng died in 375, and before his death, he warned Fu Jiān against going to war with Jin. He instead advised him to focus on consolidating his territory, as many of his conquered people, particularly the Qiang and Xianbei, were not fully loyal to his regime. However, Fu Jiān did not listen, and to address Wang Meng's latter concern, he relocated many of the Qiang and Xianbei people to live near the capital while moving the Di to newly-controlled territories, hoping to integrate the various ethnic groups.

In 378, Former Qin forces besieged Xiangyang and attacked Pengcheng. Although Xiangyang fell to Qin in 379, the assault on Pengcheng was defeated by the Jin general, Xie Xuan. In 383, aiming to unify China and despite opposition from most of his ministers, Fu Jiān invaded Jin with a massive army, with records claiming to be at 1 million strong. The Former Qin captured Shouchun before facing the Jin army led by Xie An at the Battle of Fei River. During the battle, Zhu Xu, a Former Qin general who had been captured from Jin, betrayed Fu Jiān by shouting "The Qin army is defeated!", causing widespread panic among the soldiers. As the Qin soldiers fled in disarray, the Jin army pursued and dealt them a disastrous defeat. Fu Jiān himself was injured in battle and barely escaped to the north.

Disintegration and fall

editIn 384, as Former Qin was recovering from the recent defeat, the Xianbei general and previous prince of Former Yan, Murong Chui, rebelled in the northeast, founding the Later Yan dynasty with the aim of restoring his family's former state. Chui's rebellion encouraged his nephew, Murong Hong, to revolt around Chang'an, and their state was known as the Western Yan. Fu Jiān attempted to quell the uprisings, but soon, his Qiang general, Yao Chang also rebelled north of the Wei River, founding the Later Qin dynasty. Fu Jiān was besieged in Chang'an by Western Yan forces and later fled the city due to the food shortages in 385. However, he was then captured by Yao Chang, who had him executed after he refused to formally pass the throne.

Rebellions continued to break out in other parts of the empire. In 385, the Qifu-Xianbei tribe formed the Western Qin dynasty in the Longxi and the Chouchi state was restored. In 386, Lü Guang, returning from the Western Regions, seized Liang province and founded the Later Liang, while the Tuoba-Xianbei restored their state of Dai, which later became known as the Northern Wei dynasty. Meanwhile, Xie Xuan led Eastern Jin forces to recover lost territory, pushing all the way to the Yellow River. Fu Jiān's son, Fu Pi, declared himself emperor in 385 and sought to restore Former Qin's authority from Jinyang in Bing province, but suffered a devastating defeat to the Western Yan. His brief reign came to an end after he was killed by Jin forces while trying to capture Luoyang in 386.

At Nan'an Commandery (南安郡; southeast of present-day Longxi County, Gansu) in the Guanzhong, a distant cousin of Fu Jiān, Fu Deng was acclaimed the new emperor after news of Fu Pi's death. Throughout his reign, Fu Deng fought with the Later Qin, finding much success early on before suffering a significant defeat at the Battle of Dajie in 389. From then on, he was unable to launch anymore substantial campaigns. In 394, taking advantage of Yao Chang's death, he carried out one last attack on Later Qin at the Battle of Feiqiao, where his main forces were destroyed. He was soon captured and executed by Yao Chang's successor, Yao Xing. His son, Fu Chong, fled to Huangzhong (湟中, in modern Xining, Qinghai) and declared himself emperor, but not long after, Western Qin forces seized his remaining territory and killed him in battle, marking the formal end of the Former Qin dynasty.

During the fall of Former Qin, the Fu clan became dispersed throughout China. Fu Hóng, a son of Fu Jiān, fled to the Eastern Jin, where he became a confidant of the usurper Huan Xuan before being killed in battle in 405. The Later Yan welcomed members of the Fu clan to surrender, with two of them, the sisters Fu Song'e and Fu Xunying, becoming empresses to the last ruler, Murong Xi. In Chouchi, Fu Chong's son, Fu Xuan, was made a military general.

Rulers of the Former Qin

edit| Temple name | Posthumous name | Personal name | Durations of reigns | Era names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaozu | Jingming | Fu Jian (苻健) | 351–355 | Huangshi (皇始) 351–355 |

| – | King Li¹ | Fu Sheng | 355–357 | Shouguang (壽光) 355–357 |

| Shizu | Xuanzhao | Fu Jian (苻堅) | 357–385 | Yongxing (永興) 357–359 Ganlu (甘露) 359–364 |

| – | Aiping | Fu Pi | 385–386 | Taian (太安) 385–386 |

| Taizong | Gao | Fu Deng | 386–394 | Taichu (太初) 386–394 |

| – | – | Fu Chong | several months in 394 | Yanchu (延初) 394 |

¹ Fu Sheng was posthumously given the title "wang" even though he had reigned as emperor.

Rulers family tree

edit| Former Qin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

editNotes and references

edit- ^ a b "中央研究院". 中央研究院.

- ^ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 99.

- ^ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 106.

- ^ 徐俊 (November 2000). 中国古代王朝和政权名号探源. Wuchang, Hubei: 华中师范大学出版社. pp. 107–109. ISBN 7-5622-2277-0.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.