Futurist architecture is an early-20th century form of architecture born in Italy, characterized by long dynamic lines, suggesting speed, motion, urgency and lyricism: it was a part of Futurism, an artistic movement founded by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who produced its first manifesto, the Manifesto of Futurism, in 1909. The movement attracted not only poets, musicians, and artists (such as Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Fortunato Depero, and Enrico Prampolini) but also a number of architects. A cult of the Machine Age and even a glorification of war and violence were among the themes of the Futurists - several prominent futurists were killed after volunteering to fight in World War I. The latter group included the architect Antonio Sant'Elia, who, though building little, translated the futurist vision into an urban form.[1]

History of Italian Futurism

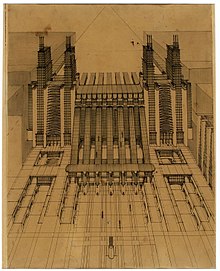

editIn 1912, three years after Marinetti's Futurist Manifesto, Antonio Sant'Elia and Mario Chiattone take part to the Nuove Tendenze[3] exhibition in Milano. Antonio Sant' Elia and Mario Chiattone were pioneers of architecture in futurism. Sant'Elia and Chiattone met in 1909 in Brera, where they were both studying architecture. Between 1913 and 1914 they shared a studio building and they participated in the first exhibition of the group Nuove Tendenze at the Famiglia Artistica in Milan (1914) as a founder-member. His exhibits included The Building of a Modern Metropolis and Bridge and Studies of Volume (watercolor and encre-de-Chine on paper). Although less abstract in character than Sant'Elia's Città Nuova drawings, scholars have said that they are among the most memorable images of Futuristic architecture.[4]

In 1914 the group presented their first exposition with a "Message" by Sant'Elia, that later, with the contribution of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, became the Manifesto dell’Architettura Futurista ("Manifesto of Futurist Architecture").[2] Boccioni unofficially worked on a similar manifesto, but Marinetti preferred Sant'Elia's paper.

Later in 1920, another manifesto was written by Virgilio Marchi, Manifesto dell’Architettura Futurista–Dinamica (Manifesto of Dynamic Instinctive Dramatic Futurist Architecture).[2] Ottorino Aloisio worked in the style established by Marchi, one example being his Casa del Fascio in Asti.

Another futurist manifesto related to architecture is the Manifesto dell'Arte Sacra Futurista ("Manifesto of Sacred Futurist Art") by Fillia (Luigi Colombo)[2] and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, published in 1931. On 27 January 1934 it was the turn of the Manifesto of Aerial Architecture by Marinetti, Angiolo Mazzoni and Mino Somenzi.[2] Mazzoni had publicly adhered to futurism only the year before. In this paper the Lingotto factory by Giacomo Matté-Trucco is defined as the first Futurist constructive invention.[2] Mazzoni himself in those years worked on a building considered today a masterpiece[5] of futurist architecture, like the Heating plant and Main controls cabin at Santa Maria Novella railway station, in Florence.

Italian Futuristic artists and architects

edit- Giacomo Balla

- Antonio Sant'Elia

- Umberto Boccioni

- Giuseppe Terragni

- Mario Ridolfi

- Eurico Prampolini

Art Deco

editThe Art Deco style of architecture with its streamlined forms was regarded as futuristic when it was in style in the 1920s and 1930s. The original name for both early and late Art Deco was Art Moderne – the name "Art Deco" did not come into use until 1968 when the term was invented in a book by Bevis Hillier. The Chrysler Building is a notable example of Art Deco futurist architecture.

Futurism after World War II

editGoogie architecture

editAfter World War II, Futurism was considerably weakened and redefined itself thanks to the enthusiasm towards the Space Age, the Atomic Age, the car culture, and the wide use of plastic. For example, this trend is found in the architecture of Googies in the 1950s in California. Futurism in this case is not a style, but a rather free and uninhibited architectural approach, which is why it was reinterpreted and transformed by generations of architects the following decades, but in general it includes amazing shapes with dynamic lines and sharp contrasts, and the use of technologically advanced materials.

Neo-Futurism

editPioneered from late 1960s and early 1970s by Finnish architects Eero Saarinen;[6][7] and Alvar Aalto,[8] American architect Adrian Wilson[9] and Charles Luckman;[10][11] Danish architects Henning Larsen[12] and Jørn Utzon;[13] the architectural movement was later named Neo-Futurism by French architect Denis Laming. He designed all of the buildings in Futuroscope, whose Kinemax is the flagship building.[14] In the early 21st century, Neo-Futurism has been relaunched by innovation designer Vito Di Bari with his vision of "cross-pollination of art and cutting edge technology for a better world" applied to the project of the city of Milan at the time of the Universal Expo 2015.[15] [citation needed] [promotion?]In popular literature, the term futuristic is often used without much precision to describe an architecture that would have the appearance of the space age as described in works of science fiction or as drawn in science fiction comic strips or comic books. Today it is sometimes confused with blob architecture or high-tech architecture. The routine use of the term futurism – although influenced by Antonio Sant'Elia's vision of Futurist architecture – must be well differentiated from the values and political implications of the Futurist movement of the years 1910–1920. The futurist architecture created since 1960 may be termed Neo-Futurism, and is also referred as Post Modern Futurism or Neo-Futuristic architecture.

-

Residential building in Paris, near the Maison de la Radio

-

Ferrohouse in Zurich (Justus Dahinden, 1970)

-

Graduate Center (classroom building), Oral Roberts University (Frank Wallace, 1963)

-

French embassy in Warsaw, Poland (Bernard Zehrfuss), 1971

-

Warsaw Central railway station in Poland by Arseniusz Romanowicz (1975)

References

edit- ^ Günter Berghaus (2000). International Futurism in Arts and Literature. Walter de Gruyter. p. 364. ISBN 3-11-015681-4.

- ^ a b c d e f "Futurist architecture and Angiolo Mazzoni’s manifesto of aerial architecture", published in VV.AA. Angiolo Mazzoni e l'Architettura Futurista, p.7–22

- ^ Literally "New Trends".

- ^ Agustín, M. R. J. (2008). Arquitectura Futurista. Síntesis. https://smu.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma9929261103403716&context=L&vid=01SMU_INST:01SMU&lang=en&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&query=any,contains,ocn299943493

- ^ In 1978, architect Léon Krier described the heating plant as the greatest masterpiece of Futurist-Constructivist-Modernist architecture. Published in London 1978 – An architecture thesis on Angiolo Mazzoni by Flavio Mangione and Barbara Weiss; Angiolo Mazzoni e l'Architettura Futurista p.45

- ^ "Eero Saarinen – Tag – ArchDaily". Archdaily.com. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Eero Saarinen's TWA Terminal To Become A Luxury Hotel". Fastcodesign.com. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Design Spotlight: Alvar Aalto- Travel Squire". Travelsquire.com. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Adrian Wilson Bio, latest news and articles – Architectural Digest". Architectural Digest. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Pearman, Hugh (1 November 2004). Airports: A Century of Architecture. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-5012-X.

- ^ "December 2012 Members Newsletter" (PDF). Preservationdallas.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Cake, Opera (19 October 2010). "Neo-Futurism at Danish Royal Opera". Opera-cake.blogspot.com. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Sydney Opera House, Sydney". Skyscraperpage.com. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Denis Laming – Architect". Laming.fr. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-25. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources

edit- VV.AA. Angiolo Mazzoni e l'Architettura Futurista, Supplement of CE.S.A.R. September/December 2008 (Available at "Centro Studi Architettura Razionalista – Research centre for rationalist a architecture – Notebooks". 2011-01-11. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11.) (in Italian and English)