Buyeo[1] (Korean: 부여; Korean pronunciation: [pu.jʌ]; Chinese: 夫餘/扶餘; pinyin: Fūyú/Fúyú), also rendered as Puyŏ[2][3] or Fuyu,[1][3][4][5] was an ancient kingdom that was centered in northern Manchuria in modern-day northeast China. It had ties to the Yemaek people, who are considered to be the ancestors of modern Koreans.[6][7][8] Buyeo is considered a major predecessor of the Korean kingdoms of Goguryeo and Baekje.

Buyeo | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2nd century BC–494 AD | |||||||||||

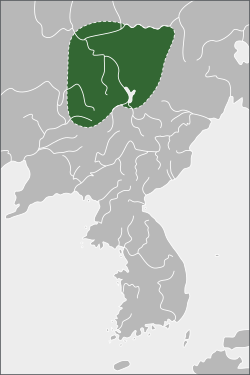

Map of Buyeo (3rd century) | |||||||||||

| Capital | Buyeo | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Buyeo, Classical Chinese (literary) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Shamanism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• ?–? | Hae Mo-su? | ||||||||||

• 86 – 48 BC | Buru | ||||||||||

• ? – 494 AD | Jan (孱) (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient | ||||||||||

• Established | c. 2nd century BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 494 AD | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||||

| Buyeo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 夫餘 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 夫余 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 부여 | ||||||

| Hanja | 夫餘 | ||||||

| |||||||

According to the Book of the Later Han, Buyeo was initially placed under the jurisdiction of the Xuantu Commandery,[9] one of Four Commanderies of Han in the later Western Han. Buyeo entered into formal diplomatic relations with the Eastern Han dynasty by the mid-1st century AD as an important ally of that empire to check the Xianbei and Goguryeo threats. Jurisdiction of Buyeo was then placed under the Liaodong Commandery of the Eastern Han.[10] After an incapacitating Xianbei invasion in 285, Buyeo was restored with help from the Jin dynasty. This, however, marked the beginning of a period of decline. A second Xianbei invasion in 346 finally destroyed the state excepting remnants in its core region; these survived as vassals of Goguryeo until their final annexation in 494.[11]

Inhabitants of Buyeo included the Yemaek tribe.[12][13] There are no scholarly consensus on the classification of the languages spoken by the Puyo, with theories including Japonic,[14] Amuric[15] and a separate branch of macro-Tungusic.[16] According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, the Buyeo language was similar to those of Goguryeo and Ye, and the language of Okjeo was only slightly different from them.[17] Both Goguryeo and Baekje, two of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, considered themselves Buyeo's successors.[18][19][20]

Mythical origins

editThe mythical founder of the Buyeo kingdom was Hae Mo-su, the Dongmyeong of Buyeo which literally means Holy King of Buyeo. After its foundation, the son of heaven (Hae Mo-su Korean: 해모수; Hanja: 解慕漱) brought the royal court to his new palace, and he was proclaimed to be King.[citation needed]

Jumong, the founder of Goguryeo, is described as the son of Hae Mo-su and Lady Yuhwa (Korean: 유화부인; Hanja: 柳花夫人) who was the daughter of Habaek (Korean: 하백; Hanja: 河伯), the god of the Amnok River or, according to an alternative interpretation, the sun god Haebak (Korean: 해밝).[21][22][23][24][excessive citations]

History

editArchaeological predecessors

editThe Buyeo state emerged from the Bronze Age polities of the Xituanshan and Liangquan archaeological cultures in the context of trade with various Chinese polities.[25] In particular was the state of Yan which introduced iron technology to Manchuria and the Korean peninsula after its conquest of Liaodong in the early third century BC.[26][page range too broad]

Relations with Chinese dynasties

editIn the later Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD), Buyeo established close ties with the Xuantu Commandery, one of Four Commanderies of Han according to the Book of the Later Han volume 85 Treatise on the Dongyi,[27] although it proceeded to becoming a nominal tributary-state and practical ally of Eastern Han in 49 AD.[28] This was advantageous to the Han as an ally in the northeast would curb the threats of the Xianbei in western Manchuria and eastern Mongolia and Goguryeo in the Liaodong region and the northern Korean peninsula. The Buyeo elites also sought this arrangement as it legitimized their rule and gave them better access to Han's prestige trade goods.[29]

During a period of turmoil in China's northeast, Buyeo attacked some of Eastern Han's holdings in 111, but relations were mended in 120 and thus a military alliance was arranged. Two years later, Buyeo sent troops to the Xuantu commandery to prevent it from being destroyed by Goguryeo when it sent reinforcement to break the siege of the commandery seat.[30] In AD 167, Buyeo attacked the Xuantu commandery but was defeated.[31] When Emperor Xian (AD 189 – AD 220) ruled Eastern Han, Buyeo was reclassified as a tributary of the Liaodong Commandery of Han.[27]

In the early 3rd century, Gongsun Du, a Chinese warlord in Liaodong, supported Buyeo to counter Xianbei in the north and Goguryeo in the east. After destroying the Gongsun family, the northern Chinese state of Cao Wei sent Guanqiu Jian to attack Goguryeo. Part of the expeditionary force led by Wang Qi (Korean: 왕기; Hanja: 王頎), the Grand Administrator of the Xuantu Commandery, pursued the Guguryeo court eastward through Okjeo and into the lands of the Yilou. On their return journey they were welcomed as they passed through the land of Buyeo. It brought detailed information of the kingdom to China.[32]

In 285 the Murong tribe of the Xianbei, led by Murong Hui, invaded Buyeo,[33] pushing King Uiryeo (依慮) to suicide, and forcing the relocation of the court to Okjeo.[34] Considering its friendly relationship with the Jin Dynasty, Emperor Wu helped King Uira (依羅) revive Buyeo.[35] According to accounts in the Zizhi Tongjian and the Book of Jin, the Murong attacked the Buyeo and forced the Buyeo to relocate several times in the 4th century.[1]

Goguryeo's attack sometime before 347 caused further decline. Having lost its stronghold on the Ashi River (within modern Harbin), Buyeo moved southwestward to Nong'an. Around 347, Buyeo was attacked by Murong Huang of the Former Yan, and King Hyeon (玄) was captured.[36][page needed][37][page range too broad]

Fall

editAccording to Samguk sagi, in 504, the tribute emissary Yesilbu mentions that the gold of Buyeo could no longer be obtainable for tribute as Buyeo had been driven out by the Malgal and the Somna and absorbed into Baekje. It is also shown that the Emperor Xuanwu of Northern Wei wished that Buyeo would regain its former glory.[citation needed]

A remnant of Buyeo seems to have lingered around modern Harbin area under the influence of Goguryeo. Buyeo paid tribute once to Northern Wei in 457–8,[38] but otherwise seems to have been controlled by Goguryeo. In 494, Buyeo were under attack by the rising Wuji (also known as the Mohe, Korean: 물길; Hanja: 勿吉), and the Buyeo court moved and surrendered to Goguryeo.[39]

Jolbon Buyeo

editMany ancient historical records indicate the "Jolbon Buyeo" (Korean: 졸본부여; Hanja: 卒本夫餘), apparently referring to the incipient Goguryeo or its capital city.[40][page range too broad] In 37 BC, Jumong became the first king of Goguryeo. Jumong went on to conquer Okjeo, Dongye, and Haengin, regaining some of Buyeo and former territory of Gojoseon.[40][page range too broad]

Culture

editAccording to Chapter 30 "Description of the Eastern Archerians, Dongyi" in the Chinese Records of the Three Kingdoms (3rd century), the Buyeo were agricultural people who occupied the northeastern lands in Manchuria (North-East China) beyond the great walls. The aristocratic rulers subject to the king bore the title ka (加) and were distinguished from each other by animal names, such as the dog ka and horse ka.[29]Four kas existed in Buyeo, which were horse ka, cow ka, pig ka, and dog ka, and ka is presumed to be of similar origin with the title khan. The ka system was similarly adopted in Goguryeo.[41]

Buyeo is north of the Long Wall, a thousand li distant from Xuantu; it is contiguous with Goguryeo on the south, with the Eumnu on the east and the Xianbei on the west, while to its north is the Ruo River. It covers an area some two thousand li square, and its households number eight myriads. Its people are sedentary, possessing houses, storehouses, and prisons. With their many tumuli and broad marshes, theirs is the most level and open of the Eastern Dongyi archerian territories. Their land is suitable for cultivation of the five grains; they do not produce the five fruits. Their people are coarsely big; by temperament strong and brave, assiduous and generous, they are not prone to brigandage... For their dress within their state they favor white; they have large sleeves, gowns, and trousers, and on their feet they wear leather sandals... The people of their state are good at raising domestic animals; they also produce famous horses, red jade, sables, and beautiful pearls... For weapons they have bows, arrows, knives, and shields; each household has its own armorer. The elders of the state speak of themselves as alien refugees of long ago. The forts they build are round and have a resemblance to prisons. Old and young, they sing when walking along the road whether it be day or night; all day long the sound of their voice never ceases... When facing the enemy the several Ka themselves do battle; the lower households carry provisions for them to eat and drink.[42]

The same text states that the Buyeo language was similar to those of its southern neighbours Goguryeo and Ye, and that the language of Okjeo was only slightly different from them.[17] Based on this account, Lee Ki-Moon grouped the four languages as the Puyŏ languages, contemporaneous with the Han languages of the Samhan confederacies in southern Korea.[43]

The earliest mentions of the Korean practice of wearing Minbok[44] are also from this source.[40][44] The text reads:[45]

In Buyeo, white clothing is revered, so they wear wide-sleeved dopo and baji made from white linens, as well as leather shoes.

Law

editBuyeo had a law that makes the thief reimburse the price that is equivalent to twelve times of the original amount the person stole, and had an eye to eye approach in terms of law.[46]

Legacy

editIn the 1930s, Chinese historian Jin Yufu (金毓黻) developed a linear model of descent for the people of Manchuria and northern Korea, from the kingdoms of Buyeo, Goguryeo, and Baekje, to the modern Korean nationality. Later historians of Northeast China built upon this influential model.[47]

Goguryeo and Baekje, two of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, considered themselves successors of Buyeo. King Onjo, the founder of Baekje, is said to have been a son of King Dongmyeong, founder of Goguryeo. Baekje officially changed its name to Nambuyeo (South Buyeo, Korean: 남부여; Hanja: 南夫餘) in 538.[48] Goryeo also considered itself a descendant of Buyeo through their direct ancestral ties with Goguryeo and Baekje. This is seen in their representation of palace names that were named after former kingdoms that were considered their forefathers.[49]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Escher, Julia (2021). "Müller Shing / Thomas O. Höllmann / Sonja Filip: Early Medieval North China: Archaeological and Textual Evidence". Asiatische Studien - Études Asiatiques. 74 (3): 743–752. doi:10.1515/asia-2021-0004. S2CID 233235889.

- ^ Byington 2016.

- ^ a b Pak, Yangjin (1999). "Contested ethnicities and ancient homelands in northeast Chinese archaeology: the case of Koguryo and Puyo archaeology". Antiquity. 73 (281): 613–618. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00065182. S2CID 161205510.

- ^ Smallwood, Colonel (1931). "Manchuria and Mongolia: Glimpses at both". Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society. 19 (1): 101–120. doi:10.1080/03068373208725190.

- ^ Beardsley, Richard K.; Smith, Robert J., eds. (1962). Japanese Culture Its Development and Characteristics. Routledge. pp. 12–16. ISBN 9780415869270.

- ^ Byington 2016, pp. 20–30.

- ^ Barnes, Gina (2015). State Formation in Korea: Emerging Elites. UK: Routledge. pp. 26–33. ISBN 9781138862449.

- ^ Jo, Yeongkwang (2015). "The Origin and Meaning of the Naming of Yemaek, Buyeo, Goguryo". Ancient Korean History Society. 44: 101–122.

- ^ "夫餘本屬玄菟", Dongyi, Fuyu chapter of the Book of the Later Han

- ^ "獻帝時, 其王求屬遼東云", Dongyi, Fuyu chapter of the Book of the Later Han

- ^ La Universidad de Seúl, 《Seoul Journal of Korean Studies,》, Vol.17, 2004. p.16

- ^ 노태돈 (1995). 부여(夫餘) [Buyeo]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2021-09-16.

- ^ 노태돈; 김선주 (2009) [1995]. 예맥(濊貊) [Yemaek]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2021-09-16.

- ^ Beckwith, C.I. (2007). "The ethnolinguistic history of Koguryo". Koguryo: The Language of Japan's Continental Relatives. Brill. pp. 29–49.

- ^ Janhunen, Juha (2005). "The lost languages of Koguryo" (PDF). Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies. 2 (2).

- ^ Unger, J Marshall (2001). "Layers of Words and Volcanic Ash in Japan and Korea". The Journal of Japanese Studies. 27 (1): 81–111. doi:10.2307/3591937. JSTOR 3591937.

- ^ a b Lee & Ramsey 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Lee, Hee Seong (2020). "Renaming of the State of King Seong in Baekjae and His Political Intention". 한국고대사탐구학회. 34: 413–466.

- ^ Park, Gi-bum (2011). "The Lineage and Establishment of the Foundation Myths of Buyeo and Koguryo : An Analysis of "Kogi" Cited in "Northern Buyeo Articles" in Samguk yusa". 동북아역사재단. 34: 205–244.

- ^ Jo, Yeong-gwang (2017). "About the origin of the Buyeo clan of Baekje monarchy". Korea Ancient History Society. 53: 169–194.

- ^ 유화부인 柳花夫人. Doosan Encyclopedia.

- ^ Doosan Encyclopedia 하백 河伯. Doosan Encyclopedia.

- ^ 하백 河伯. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ 조현설. 유화부인. Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Byington 2016, pp. 62, 101.

- ^ Kim, Sangmin (2018). "Expansion of Iron Culture in Northeast Asia and Gojoseon". Hanguk Kogo-Hakbo. 107: 46–71.

- ^ a b Book of the Later Han Volume 85 Treatise on the Dongyi

- ^ Byington 2016, p. 146.

- ^ a b Byington 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Byington 2016, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Fan, Ye (167). "Book of the Later Han, Year 167 AD". Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

- ^ Ikeuchi, Hiroshi. "The Chinese Expeditions to Manchuria under the Wei dynasty," Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 4 (1929): 71-119. p. 109

- ^ Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall, 《East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History》, Cengage Learning, 2013, pp.101-102

- ^ Hyŏn-hŭi Yi, Sŏng-su Pak, Nae-hyŏn Yun, 《New history of Korea:Korean studies series》, vol.30, Jimoondang, 2005. p.116

- ^ Fan, Xuanling (648). "Book of Jin (晉書), Chapter 8". Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

- ^ Sima, Guang (1084). Zizhi-Tongjian (in Traditional Chinese).

- ^ Lee, Jeong-bin (2017). "Hostages of Buyeo and Goguryeo in the Former Yan of Murong Xianbei". Northeast Asian History Foundation. 57: 76–114.

- ^ Northeast Asian History Foundation, 《Journal of Northeast Asian History》, Vol.4-1-2, 2007. p.100

- ^ La Universidad de Seúl, 《Seoul Journal of Korean Studies,》, Vol.17, 2004. p.16

- ^ a b c Lim, Ki-hwan (2019). "Research on formation of Sonobu(消奴部) and Gyerubu(桂婁部) in the Jolbon(卒本), the early Koguryo Dynasty". Korean Historical Studies. 136: 5–46.

- ^ 가. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ Lee 1993, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey 2011, pp. 34–36.

- ^ a b 이, 주상 (2023-06-11). "'백의민족' 옷 색깔은?…"흰색 아닌 소색입니다"". SBS News (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ 김, 종성 (2011-03-11). "한민족은 '백의민족'? 원조는 따로 있습니다". OhmyNews (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ 1책12법. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ Byington, Mark. "History News Network | The War of Words Between South Korea and China Over An Ancient Kingdom: Why Both Sides Are Misguided". Hnn.us. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ^ Il-yeon: Samguk Yusa: Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea, translated by Tae-Hung Ha and Grafton K. Mintz. Book Two, page 119. Silk Pagoda (2006). ISBN 1-59654-348-5

- ^ "고려시대 史料 Database". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

Bibliography

edit- Byington, Mark E. (2016), The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory, Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8

- Lee, Peter H. (1993), Sourcebook of Korean Civilization 1, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-07912-9

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011), A History of the Korean Language, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49448-9