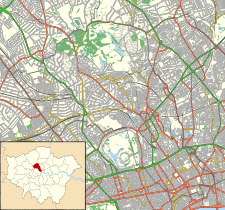

Great Ormond Street Hospital (informally GOSH, formerly the Hospital for Sick Children) is a children's hospital located in the Bloomsbury area of the London Borough of Camden, and a part of Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust.

| Great Ormond Street Hospital | |

|---|---|

| Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust | |

The view along Great Ormond Street | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Great Ormond Street, London, England |

| Coordinates | 51°31′21″N 0°07′14″W / 51.5225°N 0.1205°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | National Health Service |

| Type | Teaching |

| Affiliated university | University College London |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | No |

| Beds | 389 |

| Speciality | Children's hospital |

| History | |

| Opened | 14 February 1852 |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

The hospital is the largest centre for child heart surgery in Britain and one of the largest centres for heart transplantation in the world. In 1962 it developed the first heart and lung bypass machine for children. With children's book author Roald Dahl, it developed an improved shunt valve for children with hydrocephalus, and non-invasive (percutaneous) heart valve replacements. Great Ormond Street performed the first UK clinical trials of the rubella vaccine, and the first bone marrow transplant and gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency.[1]

The hospital is the largest centre for research and postgraduate teaching in children's health in Europe.[2]

In 1929, J. M. Barrie donated the copyright to Peter Pan to the hospital.

History

editOrigins

editThe Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street was founded on 14 February 1852 after a long campaign by Dr Charles West, and was the first hospital in England to provide in-patient beds specifically for children.[3]

Despite opening with just 10 beds, it grew into one of the world's leading children's hospitals through the patronage of Queen Victoria, counting Charles Dickens, a personal friend of the Chief Physician Dr West, as one of its first fundraisers. The Nurses League was formed in February 1937.[4]

Nationalisation

editGreat Ormond Street Hospital was nationalised in 1948, becoming part of the National Health Service. During the early years of the NHS, private fundraising for the hospital was heavily restricted, though the hospital was permitted to continue to receive pre-existing legacies.[5]

Audrey Callaghan, wife of James Callaghan (prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979), served the hospital as Chairman of the Board of Governors from 1968 to 1972 and then as Chairman of the Special Trustees from 1983 until her final retirement in 1990.[6] Diana, Princess of Wales, served as president of the hospital from 1989 until her death. A plaque at the entrance of the hospital commemorates her services.[7]

1990s

editThe Charles West School of Nursing transferred from Great Ormond Street to London South Bank University in 1995.[8]

2000s

editIn 2002 Great Ormond Street Hospital commenced a redevelopment programme which is budgeted at £343 million and the next phase of which was scheduled to be complete by the end of 2016.[9] In July 2012, Great Ormond Street Hospital was featured in the opening ceremony of the London Summer Olympics.[10][11]

In 2017 Great Ormond Street Hospital was subject to international attention regarding the Charlie Gard treatment controversy.[12][13][14]

Archives

editThe hospital's archives are available for research under the terms of the Public Records Act 1958 and a catalogue is available on request.[15] Admission records from 1852 to 1914 have been made available online on the Historic Hospital Admission Records Project.[16]

St Christopher's Chapel

editSt Christopher's Chapel is a chapel decorated in the Byzantine style and Grade II* listed building located in the Variety Club Building of the hospital. Designed by Edward Middleton Barry (son of the architect Sir Charles Barry who designed the Houses of Parliament) and built in 1875, it is dedicated to the memory of Caroline Barry, the architect's sister-in-law, who provided the £40,000 required to build the chapel and a stipend for the chaplain.[17] It was built in "elaborate Franco-Italianate style". As the chapel exists to provide pastoral care to ill children and their families, many of its details refer to childhood. The stained glass depicts the Nativity, the childhood of Christ and biblical scenes related to children. The dome depicts a pelican pecking at her breast in order to feed her young with drops of her own blood, a traditional symbol of Christ's sacrifice for humanity.[18]

When the old hospital was being demolished in the late 1980s, the chapel was moved to its present location via a "concrete raft" to prevent any damage en route. The stained glass and furniture were temporarily removed for restoration and repair. It was reopened along with the new Variety Club Building on 14 February 1994 by Diana, Princess of Wales, then president of the hospital.[19]

Peter Pan

editIn April 1929 J. M. Barrie gave the copyright to his Peter Pan works to the hospital, with the request that the income from this source not be disclosed. This gave the institution control of the rights to these works, and entitled it to royalties from any performance or publication of the play and derivative works. Innumerable performances of the play and its various adaptations have been staged, several theatrical and television adaptations have also been produced, and numerous editions of the novel have been published, all under licence from the hospital.[20][21] The hospital's trustees further commissioned a sequel novel, Peter Pan in Scarlet, written by Geraldine McCaughrean and published in 2006.[22][23]

After the copyright first expired in the UK at the end of 1987 – 50 years after Barrie's death – the government's Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988[24] granted the hospital a perpetual right to collect royalties for public performances and commercial publication of the work within the UK. This did not grant the hospital full copyright control over the work, however. When British copyright terms were later extended to the author's life plus 70 years by a European Union directive in 1996, Great Ormond Street revived its full copyright claim on the work. After the copyright expired again in 2007, the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act again applied.[24]

Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity

editThe hospital has relied on charitable support since it first opened. One of the main sources for this support is Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. Whilst the NHS meets the day-to-day running costs of the hospital, the fundraising income allows Great Ormond Street Hospital to remain at the forefront of child healthcare.[25] The charity aims to raise over £50 million every year to complete the next two phases of redevelopment, as well as provide substantially more fundraising directly for research. The charity also purchases up-to-date equipment, and provides accommodation for families and staff.[26][27]

Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity was one of the charities that benefited from the national Jeans for Genes campaign, which encourages people across Britain to wear their jeans and make a donation to help children affected by genetic disorders. All Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity's proceeds from the campaign went to its research partner, the UCL Institute of Child Health.[28]

On 6 August 2009, Arsenal F.C. confirmed that Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity was to be their "charity of the season" for the 2009–10 season. They raised over £800,000 for a new lung function unit at the hospital.[29]

Two charity singles have been released in aid of the hospital. In 1987, "The Wishing Well", recorded by an ensemble line-up including Boy George, Peter Cox and Dollar amongst others became a top 30 hit.[30] In 2009, The X Factor finalists covered Michael Jackson's "You Are Not Alone" in aid of the charity, reaching No.1 in the UK Charts.[31]

On 30 March 2010, Channel 4 staged the first Channel 4's Comedy Gala at the O2 Arena in London, in aid of the charity. The event has been repeated every year since, raising money for Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity each time.[32]

In 2011, Daniel Boys recorded a charity single called "The World Is Something You Can Imagine". It was also released as with proceeds going to the Disney Appeal at Great Ormond Street Hospital.[33]

In 2018, celebrity supergroup The Celebs formed at Metropolis Studios to record an original Christmas song called "Rock With Rudolph", written and produced by Grahame and Jack Corbyn. The song was in aid of Great Ormond Street Hospital. It was released digitally through independent record label Saga Entertainment in November 2018. The music video debuted exclusively with The Sun on 29 November 2018 and had its first TV showing on Good Morning Britain on 30 November 2018. The song peaked at number two on the iTunes pop chart.[34][35][36]

Controversies

editPeter Pan copyright

editAt various times, Great Ormond Street has been involved in legal disputes in the United States, where the copyright term is based on date of publication, putting the 1911 novel in the public domain since the 1960s. The hospital asserted that the play, first published in 1928, was still under copyright in the US until the end of 2023.[37]

Gender identity

editIn January 2024 it was revealed that proposed gender service "has been hit by revolt before it has opened after several experts quit over apparent concerns with staff training" and that "The resignations included experts who believed the training materials were not following the independent recommendations made by Dr Hilary Cass, former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Namely, that the service should provide an "exploratory" rather than "affirmative" approach to the child's health". Some clinicians working on the new training materials and who did not resign are understood to have felt it important to affirm a patient’s gender identity and know that patients benefit from medication.[38][39] This recommendation has also been criticised, due to ethical concerns around the nature of an "exploratory" approach. Specifically, that it will result in biased clinicians carrying out conversion therapy.[40]

On 1 April 2024, despite opposition, the new Children and Young People's Gender Service (London) began delivering for children and young people experiencing gender related distress.[41]

Despite resistance to the service, the hospital has assured the public that their aim "is to develop a robust training and education programme that is underpinned by the latest evidence that can enable clinicians and support staff to deliver the very best care for the children and young people who urgently need this new service" [42]

In March 2024 NHS England confirmed children attending the regional centres will no longer receive puberty blockers and will be supported in line with the recommendations made by Dr Hilary Cass by "resulting in a holistic approach to care".[43] One of the last acts of government in 2024 was to bring in an emergency ban on puberty blockers.[44]

Fundraising

editThe hospital's charity faced an investigation by the Information Commissioner's Office over potential breaches of data protection law in February 2017.[45] The Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity was fined "£11,000 for sharing 910,283 records with other charities, sending on average 795,000 records per month to a wealth screening company and using email and birthdays to find out extra information about more than 311,000 supporters".[46][47]

In 2024 Fundraisers working on behalf of Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity have found themselves embroiled in controversy due to allegations of employing "pressure-selling techniques". These door-to-door fundraisers have been accused of coercing people into signing up for donations.[48] An undercover investigation exposed some concerning practices such as:[48]

- Psychological manipulation: Fundraisers were taught to use "psychological motivators" and anticipate objections when interacting with potential donors at their doorsteps. This included tactics to encourage regular monthly donations via direct debit, allowing the hospital to better plan its budget.

- Emotional manipulation: One senior fundraiser even claimed the ability to cry on demand to evoke sympathy from potential donors.

- Hard-sell tactics: Trainees were armed with an array of hard-sell techniques designed to overcome any objections raised by potential donors.

Other

editGreat Ormond Street Hospital was involved in a scandal regarding the removal of live tissue and organs from children during surgery and onward sale to pharmaceutical companies without the knowledge of parents in 2001.[49]

In January 2014, it was revealed that as a result of an accidental injection of glue into her brain, Maisha Najeeb brought a claim for compensation against the Great Ormond Street Hospital leading to a payment of up to £24million.[50][51]

The hospital's charity faced an investigation by the Information Commissioner's Office over potential breaches of data protection law in February 2017.[45] The Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity was fined "£11,000 for sharing 910,283 records with other charities, sending on average 795,000 records per month to a wealth screening company and using email and birthdays to find out extra information about more than 311,000 supporters".[46][47]

In April 2018, it was revealed children were put at risk by being given potentially dangerous drugs.[52]

In April 2019, following an inquiry into the death of Amy Allan, the coroner criticised the hospital for not providing a proper plan for the teenager's recovery after surgery.[53]

In 2019 the Great Ormond Street mortuary manager made the senior leadership aware of staffing issues. "Since April 2019 GOSH mortuary has been very short staffed but somehow we have managed to keep our standards up, get through a HTA inspection and still give 100% care to our patients whilst having 50% staff. Patient first and always".[54]

The former Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, urged Great Ormond Street Hospital to examine a possible fundamental cultural problem amid claims it prioritizes reputation over patient care in March 2020.[55]

In March 2020, the BBC conducted an investigation into the death of a child and revealed that at least six children had died of invasive aspergillosis at Great Ormond Street since 2016.[56]

Several leaked emails from the head of Great Ormond Street Hospital, released in November 2020, suggested that the hospital had become accustomed to some "bad behaviours" and that more needed to be done to ensure staff feel safe.[57]

In June 2021, the mother of a baby questioned why action was not taken sooner for her son who died at Great Ormond Street Hospital.[58]

Great Ormond Street Hospital entered into an agreement with Sensyne, an AI company, in September 2021. The hospital received 1,428,571 shares in the company in exchange for patient data. Sensyne has since been delisted from the London Stock Exchange leading to a loss to the hospital of around £2 million.[59][60]

Following a lawsuit against Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, a family received up to £7 million after the boy was left disabled, in July 2022.[61][62][63]

In February 2023, the mother of a sick child with cancer was shocked after hearing Great Ormond Street hospital workers making jokes about his likely death.[64][65][66][67]

In March 2023, it was revealed trainee dentist doctors at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust were going unsupervised.[68]

In May 2023, newspapers highlighted the case of Ryan, left unattended in a lift by a Great Ormond Street hospital worker. His mother Catherine suffered a stress-induced seizure as she fell down the stairs and broke several bones after learning what happened to her son. Ryan was found again after someone needed to use the trolley he was in, around 11 hours later. A spokesperson from the hospital said that there was a situation on the day of Ryan’s arrival and that they had half the number of staff that were due to be on duty.[69][70]

Hospital cleaners have made allegations of institutional racism at Great Ormond Street Hospital in March 2023. Hospital cleaners from minority ethnic groups say they were denied NHS contracts and paid less than white NHS employees. A court hearing was concluded in 2023. Each cleaner could receive between £80,000 and £190,000 if the claims are successful.[71]

In August 2023 it was revealed a child began to experience lung complications with an invasive aspergillosis infection which led to his death.[72]

In 2024 it was revealed that hundreds of children at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) have suffered life-altering injuries, including amputations, permanent deformities, and chronic pain, following their treatment by the consultant ortopedic surgeon Yaser Jabbar.[73]

Patients-led assessments

editFood quality

editIn 2013 a survey of more than 1,300 health units revealed Great Ormond Street Hospital had the second worst score in London and the 13th lowest score overall. The hospital that treats some of the country's most severely ill children and teenagers said it was surprised by the results of the first patient-led assessment of non-clinical issues. According to a hospital spokeswoman, the food quality has now improved "after extensive taste testing."[74]

In 2023 a new patient-led assessment released by NHS Digital revealed Great Ormond Street Hospital was still ranked amongst the worst hospitals in UK with the 40th lowest score overall. As part of the assessment of food provision, assessors were asked questions regarding the choice of food offered, the availability of food 24 hours a day, meal times, and menu accessibility. A ward-level assessment of the food was also conducted, including an assessment of taste, texture, and serving temperature.[75]

Cleanliness

editin 2023 the patients-led assessment data released by NHS Digital also revealed Great Ormond Street Hospital was the third worst hospital in UK for cleanliness.[75]

Notable staff

edit- Lancelot Barrington-Ward, surgeon

- Mildred Creak, child psychiatrist

- Norman Bethune, Canadian physician and humanitarian

- Gwendoline Kirby, matron 1950-

- H. S. Sington, anaesthetist 1907 to 1938

- Lewis Spitz, surgeon

- Catherine Jane Wood, Matron from 1880

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Breakthroughs "Breakthroughs | Great Ormond Street Hospital". Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Britain's best hospitals: A patients' guide". The Independent. 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Kevin Telfer (2008). The remarkable story of Great Ormond Street Hospital. Simon & Schuster. p11

- ^ "www.gosnursesleague.org". Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ Official history Retrieved 14 February 2019

- ^ Kevin Telfer (2008). The remarkable story of Great Ormond Street Hospital. Simon & Schuster. p58

- ^ "Princess Diana unveils plaque at Great Ormond Street Hospital". Getty Images. March 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Complete history of GOSH". Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ "The New Clinical Building (Phase 2B)". Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "World's media lavishes praise on Olympic opening ceremony". The Guardian. Guardian. 28 July 2012. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "Incredible honour for Great Ormond Street Hospital at London 2012 Olympic Opening Ceremony". Great Ormond Street Hospital. UK NHS/ UK Government. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "London's Great Ormond Street Hospital seeks new hearing for critically ill Charlie Gard". Reuters. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Jacobs, Ben; Pidd, Helen (3 July 2017). "Donald Trump offers help for terminally ill baby Charlie Gard". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Clarke, Hilary (3 July 2017). "Pope and Trump offer support to Charlie Gard". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Archives". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Historic Hospital Admission Records Project". Archived from the original on 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Ian Visits GOSH". Ian Visits. 11 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Historic England. "Great Ormond Street Hospital Chapel in Central Block (1113211)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Lunnon, Raymond J. "The Chapel of St. Christopher" (pdf). Great Ormond Street Hospital. Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Tatar, Maria (ed). The Annotated Peter Pan. W.W. Norton (2011)

- ^ Bruce K. Hanson. Peter Pan on Stage and Screen 1904–2010. McFarland (2011)

- ^ Philip Ardagh (8 October 2006). "Return to Neverland". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- ^ Nicola Smyth (8 October 2006). "The Boys are back in town". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012.

- ^ "GOSH.org". Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ "What's happening now". Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Why we need your help". Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Jeans for Genes to set up as independent charity". UK Fundraising. 23 May 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Arsenal.com". Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ "G.O.S.H. – Full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "X Factor Finalists 2009 – Full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "Channel 4's Comedy Gala". The O2. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ ""The World Is Something You Imagine" for our Disney Appeal". gosh.org. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Barker, Faye (30 November 2018). "TV stars sing for Great Ormond Street Christmas charity single". ITV News. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Gail Porter discusses recording a celebrity charity single for Great Ormond Street Hospital". Female First. 4 December 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "The Celebs – Rock With Rudolph". YouTube. TheCelebsVEVO. 29 November 2018. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Copyright". Archived from the original on 3 July 2010.

- ^ Gentleman, Amelia (18 January 2024). "New NHS children's gender clinic hit by disagreements and resignations". Guardian.

- ^ Searles, Michael (18 January 2024). "GOSH advisers quit new NHS children's gender clinic over training concerns". The Telegraph.

- ^ PsychologyScience, Perspect (18 March 2023). "Interrogating Gender-Exploratory Therapy".

- ^ "New specialist gender service starts". www.evelinalondon.nhs.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2024.

- ^ "Statement on media coverage on new children and young people's gender service". Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. 14 April 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Stavrou, Athena (12 March 2024). "NHS says children to no longer receive puberty blockers at gender identity clinics". Yahoo News.

- ^ "Private prescriptions of puberty blockers for children to be banned". The Telegraph. 29 May 2024. Retrieved 3 June 2024.

- ^ a b Cooney, Rebecca. "Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity 'cooperating with ICO'". www.thirdsector.co.uk.

- ^ a b Rudgard, Olivia (5 April 2017). "Britain's biggest charities hiring investigators to snoop on their wealthiest donors as ICO announces host of fines". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ a b Bowcott, Owen; correspondent, Owen Bowcott Legal affairs (5 April 2017). "UK charities fined by watchdog for wealth screening of donors". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Beal, James (22 February 2024). "Revealed: how charity doorsteppers twist your emotions for money". The Times.

- ^ Miller, Marjorie (31 January 2001). "British Stunned by Harvest of Organs at a Children's Hospital". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hartley-Parkinson, Richard (27 January 2014). "Brain damaged girl handed £24million payout after her head was injected with GLUE by medics". mirror.

- ^ "Hospital payout for girl's glue injection". BBC News. 27 January 2014.

- ^ Newman, Melanie; Campbell, Denis (14 April 2018). "Patients put at risk by 'aggressive' treatment at Great Ormond Street". The Observer – via The Guardian.

- ^ "Great Ormond Street Hospital under fire over death of teenager Amy Allan following 'uneventful' surgery". ITV News. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Great Ormond Street Hospital - mortuary team award". Association of Anatomical Pathology Technology.

- ^ "Child deaths 'not properly investigated' at top hospital". 17 March 2020 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Buchanan, Michael (17 March 2020). "Child deaths 'not properly investigated' at top hospital". BBC News.

- ^ "Chief executive admits Great Ormond Street 'got used to some bad behaviours'". The Independent. 20 November 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Jacob (11 June 2021). "Mum questions treatment for 'smiley, happy baby' who died". MyLondon.

- ^ Clark, Lindsay. "NHS hospitals lose millions in AI startup investment". www.theregister.com.

- ^ Clark, Lindsay. "Patient data swapped for shares in AI firm. Then it delists". www.theregister.com.

- ^ Farmer, Brian (14 July 2022). "Great Ormond Street Hospital bosses agree settlement after boy left disabled". Evening Standard.

- ^ "Great Ormond Street Hospital bosses agree settlement after boy left disabled". The Independent. 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Great Ormond Street Hospital bosses agree settlement after boy left disabled". www.shropshirestar.com. 14 July 2022.

- ^ Thrower, Antony; Harris, Mary (23 February 2023). "Family's horror as doctors joke about 'Grim Reaper' outside their ill son's room". mirror.

- ^ "Mum of boy with cancer 'disgusted' at Great Ormond Street Hospital doctors' Grim Reaper jokes". ITV. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Mum's disgust at hospital workers' Grim Reaper jokes metres from sick child". Kent Online. 22 February 2023.

- ^ Williamson, Lucy (23 February 2023). "Mum of boy with cancer claims Great Ormond Street staff 'made Grim Reaper joke'". MyLondon.

- ^ "Great Ormond Street Hospital unable to hire dentists amid national staffing crisis". The Independent. 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Shoebury's Ryan Heffernan-Surplice was left in lift at GOSH". echonews. 27 May 2023.

- ^ "Essex boy, 12, who died suddenly at Shoeburyness High School spent 'around 11 hours' unattended in Great Ormond Street hospital lift". essexlive. 27 May 2023.

- ^ "Cleaners sue NHS hospital over 'racial discrimination'". openDemocracy.

- ^ Cuddeford, Callum (3 August 2023). "boys-death-after-last-chance" – via My London.

- ^ "721 children in rogue surgeon investigation at Great Ormond Street". The Times. 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Great Ormond Street Hospital food 'among UK worst'". Evening Standard. 25 September 2013.

- ^ a b Tidman, Zoe (11 April 2023). "Revealed: Best and worst trusts for cleanliness and food". Health Service Journal.

External links

edit- Official website

- MUSIC4GOSH Musicians working for Great Ormond Street Hospital Charity

- UCL Institute of Child Health website

- Jeans for Genes website

- Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity

- Historic Hospital Admission Records Project – containing archive of admission records for the Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street 1852–1914

- Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Nurses League website