Gaetana "Gae" Emilia Aulenti (pronounced [ˈɡaːe auˈlɛnti]; 4 December 1927 – 31 October 2012) was an Italian architect and designer based in Milan. Beginning her career in the early 1950s, Aulenti was one of the few prominent female architects in post-war Italy.[1][2]

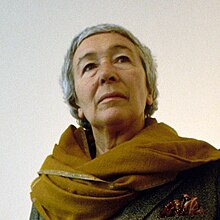

Gae Aulenti | |

|---|---|

Aulenti in 1986 | |

| Born | Gaetana Emilia Aulenti 4 December 1927 Palazzolo dello Stella, Italy |

| Died | 31 October 2012 (aged 84) Milan, Italy |

| Known for | Architectural design |

| Movement | Modernism |

At this time, modern architecture was the predominant international architectural style.[3] However, Aulenti adopted the principals of neo-liberty, a controversial architectural theory which argued for an ongoing place for tradition and history in design; for recognising artistic merit; and, for freedom of design within the modern aesthetic.[4][5][6]

Throughout her career, Aulenti used her architecture and design skills in a variety of professional forums ranging from furniture design to major architectural works.[1][7][8]

Aulenti is known for transforming the Gare d'Orsay to the Musée d'Orsay.[9] She was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion d' Honneur and in 1995, the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic.[10][11][12]

Personal life and education

editAulenti, was born in Palazzolo dello Stella in the Friuli region of northeast Italy to Aldo Aulenti, an accountant and his wife, a school teacher. The Aulenti family, with origins in Calabria and Apulia, included doctors, lawyers and clergy.[13][14]

When Aulenti was a child, her family moved to Biella, in the Piedmont region in northern Italy. During World War II, Aulenti lived in Nazi occupied Northern Italy and continued her secondary school education in Turin and Florence.[15]

In 1953, Aulenti completed her degree in architecture at the Polytechnic University of Milan.[16][9] Architects Anna Castelli Ferrieri, Franca Stagi and Cini Boeri were fellow alumni.[17][18]

Aulenti married Francesco Buzzi, also a Polytechnic alumnus, in 1959.[1] They had a daughter, Giovanna Buzzi, who became a costume designer.[19] Aulenti and Buzzi divorced when Giovanna was three years of age.[19] Giovanna said she was close to her mother and saw her as a mentor.[19]

Architectural and design philosophy

editFrom 1955 to 1965, Aulenti was a graphic designer at the Casabella-continuità, a Milanese magazine with a focus on avant-garde architecture and design.[20] While working at Casabella under editor-in-chief, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Aulenti and her colleagues explored the novel but short-lived Italian architectural theory, neo-liberty.[1][5] The theory postulated there was continuity between historic and modern architectural styles rather than strict division and that elements of the past could be used to benefit in current styles.[21] This represented a step back from modernism. Aulenti's realisation of the theory is found in her first furniture piece, Sgarsul (1962), a chair made in bent beech wood with a slung leather seat with soft polyurethane padding. The Sgarsul chair takes historic design elements from Thonet's Rocking Chair No.1. (1862).[22][23][24]

Aulenti said of her architectural and design philosophy,

I am convinced that architecture is tied to the polis, it is an art of the city, of the foundation, and as such it is necessarily related and conditioned by the context in which it is born. Place, time, and culture create that architecture, instead of another.[1]

And,

The architecture in which I would like to recognize myself derives from three fundamental capacities of an aesthetic and not a moral order. The first is the analytical one, in the sense that we must be able to recognize the continuity of both conceptual and physical urban and geographical traces, as specific essences of architecture. The second is the synthetic one, that is to know how to operate the necessary synthesis in order to render priority and evident the principles of the architecture. The third is the prophetic one, typical of artists, poets and inventors.[25][26]

Aulenti said of her range of design work,

I have always tried to make my work unclassifiable, not to accept abstract rules, not to confine myself to specializations, but instead to deal with different disciplines. The theatre, for example, to be able to analyze literary and musical texts. The design of objects as a complementary world to architectural spaces. Architecture as a basic passion where theory and practice must intertwine. I believe architecture is an interdisciplinary intellectual work, a work in which building science and art are extremely integrated.[24]

Career

editIndustrial design

editAulenti had a prolific career in industrial design.[27][28]

Aulenti's Locus Solus (1964) furniture collection was named after the country estate in Raymond Roussel's 1912 novel of the same name. It included chairs, a table, an adjustable lamp, sofa, sun lounger, and bench. The furniture was manufactured in tubular cold-formed steel by the Poltronova furniture company. The collection was used in the film La Piscine (1969). A replica collection in off-white and yellow, was produced for sale in 2023.[29][30][31]

The Pipistrello lamp (1965) was one of Aulenti's early but lasting designs.[32][33] The lamp is innovative in that the neck of the lamp extends by 20 cm so that the lamp could sit on a table or the floor.[33][2] It was manufactured by Elio Martinelli, the founder of the Martinelli Luce lighting company, using methacrylate copolymer molding.[34] Another Aulenti design for Martinelli Luce was the La Ruspa lamp (1967).[28][35]

The Giova (1964) was designed for FontanaArte, a lighting and furniture manufacturer. The Giova was a centripetal object that functioned as a lamp, a planter, an aroma diffuser and an objet d'art.[24]

Olivetti, the maker of precision office machines, engaged Aulenti to design their showrooms in Paris (1967) and Buenos Aires (1968).[36][23] The office machines were displayed on a central inverted cone of white laminate with spokes of polished wood between them. The surfaces surrounding the central display were coloured red in order to convey the feeling of one being in a futuristic capsule.[37]

In 1968, Aulenti designed showrooms in Turin, Zurich and Brussels for the car manufacturer, Fiat.[38] The cars were displayed on inclined and mirrored platforms.[39] The show room furniture was produced by the Kartell furniture company from Aulenti's designs. At the time, Kartell was experimenting with plastic injection moulding.[39][12]

Aulenti collaborated with the American modern furniture design and manufacturing company, Knoll in the late 1960s and 1970s. Their first design was the Jumbo, a table in Carrara marble. The second was a full furniture set presented as "The Aulenti Collection". It included a lounge, side chairs, and, high and low tables.[40]

Aulenti's projects were not only in furniture and display design. She worked with the French fashion house, Louis Vuitton, to design a watch with a matching pen and silk scarf. The design is known as the "Monterey" (1988). There were two versions. The Monterey I had elements of an elaborately decorated pocket watch while the Monterey II was notable for its black, polished ceramic case.[41] Aulenti also designed a line of porcelain sanitary ware, the "Orsay" collection (1996).[2]

Architectural design

editMusée d'Orsay

editThe Gare d'Orsay (Orsay railway station) was built in 1900 in the beaux-arts style by Victor Laloux.[42]

In 1975, the French president, François Mitterrand, engaged the French architectural firm, ACT to commence an adaptive reuse project, converting the railway station into a new museum, the Musée d'Orsay, which would house visual art collections created between 1848 and 1914.[43]

Aulenti was engaged to complete the new museum's interior design but discord between ACT and the curators led Aulenti to have a larger role in the overall architectural plan.[42][44] Aulenti succeeding in arguing for alterations to the ACT design, which the curators felt was excessively beholden to the neo-classical style and overly ornate. Some features of the Gare d'Orsay were preserved, including the mansard roof, a large gilded clock, large busts of Mercury (messenger of the gods) and stone rose casing of the ceiling.[43]

Aulenti divided the station space into three levels. On the ground floor, the main corridor (installed in an incline) was changed from the short to the long axis of the building. From this ramp, one entered galleries on either side. Limestone blocks, in various shades of white, were attached to the surfaces of the ramp, platforms supporting statuary and at one end, two towers.[2] Balconies overlooking the main corridor (usually called the "nave") were added at the mezzanine and attic (upper level).[45][46] Natural light enters the building from the large, glass, barrel vault ceiling, the windows facing the Rue de Lille and from oculi. With the installation of additional artificial lighting, Aulenti created a consistent quality of light throughout the museum.[43] The museum interior design has since been changed using halogen lighting, dark wood floors and grey walls.[47]

Charles Jencks, cultural theorist and architectural historian, described the Musée d'Orsay as an example of a "postmodern museum" where there is tension due to the past needing to exist in the present and the artistic in the academic.[48] Jencks said, "The train shed, a symbol of nineteenth-century power and materialism, meets thirteenth-century cathedral layout in a twentieth-century temple to the contradictions of nineteenth-century art."[49]

He wrote of the museum,

The linear, suiting trains, also suits historical sequence with startling results. They give a clear beginning, middle and end to the gentle stroll through history. Overhead, the wide barrel vault of the old station spreads a generous light that pulls one gently up the progression of French art. The floor and the visitor mount slowly, too ... Gae Aulenti has articulated the walls to either side of this nave space in heavy Egyptian tones, but also with horizontal streamlines that push forward ... thus, the railway station becomes a cathedral with the left aisle housing the avant-garde and the right aisle holding the Academy. Up the middle, the nave mixes the two competitors but not indiscriminately.[48]

The new museum opened to the public on 9 December 1986 to mixed review.[50][51][52][53] Paul Goldberger, architectural critic, wrote in The New York Times,

Unfortunately, the results of this ambitious project are, architecturally speaking, not natural at all. They are contrived, awkward and uncomfortable. The newly created Musee d'Orsay may be the most ambitious conversion of an old building into a museum in the modern history of Paris, but it is also a work of architecture that is deeply insensitive both to the original Gare d'Orsay and to the works of art it is supposed to be protecting and displaying. It will do little to advance the art of museum design, and it may well set the business of architectural ''recycling'' back a generation.[54]

Aulenti received the Chevalier de Legion d'Honneur, conferred by the president of the Republic of France, François Mitterrand in 1987 for her contribution.[1]

Centre Georges Pompidou

editThe Centre Pompidou was built between 1972 and 1977 to a plan by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. The ten-level building, constructed in glass and metal, was designed with open indoor spaces to provide flexibility in its use.[55] It is the home of the collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne.[56]

Aulenti was engaged to redesign the fourth floor of the Musée to reduce the amount of natural light striking the art works.[57] Aulenti created galleries of varying sizes along a building-length, unobstructed corridor-gallery set beside the west windows.[58] She installed shelves, alcoves and pedestals within the galleries and created small corridors linking the galleries for fragile items that required low light exposure.[59][55]

Palazzo Grassi

editThe Palazzo Grassi is a 16th century mansion on the Grand Canal in Venice. In 1983, when the Palazzo was owned by the Fiat group. Aulenti was commissioned to refurbish the palazzo as an art exhibition space.[60]

The building has two floors and an attic built around a central trapezoid-shaped courtyard. In 1983, the building was dark and maze-like with no indication of its original features.[61]

Aulenti searched in contemporaneous Venetian buildings for elements of Palazzo's original architect, Giorgio Massari. Aulenti repaired the original masonry with salvaged 19th century bricks. New utilities were fixed outside the masonry so that it would not be disturbed in the future. Paint was applied in a palette of aquamarine on pink marble-patterned stucco (marmorino).[60] Aulenti and Piero Castiglioni, an Italian lighting designer, created the Castello Lighting System for the Palazzo. The Castello system, designed for flexibility, was manufactured in aluminium with low voltage halogen bulbs. It won a Compasso d'Oro design award in 1995.[62]

The palazzo was gutted and refurbished over a thirteen month period, opening on 15 April 1985.[63]

Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya

editThe Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya in Barcelona, home of the Catalan visual art collection, was constructed on Montjuïc for the 1929 World's Fair. Aulenti and a team of designers refurbished the museum for the 1992 Summer Olympics.[64][65] They added escalators and terraces to ease access to the building. Glass was added to the outer walls for illumination. In the great hall, a structure of white metal steps was inserted to define spaces for a bookstore and cafeteria.[64]

Scuderie del Quirinale

editThe Scuderie del Quirinale (papal stables) is a building at the Quirinal Palace, the official residence of the president of Italy in Rome. Aulenti converted the Scuderie to an exhibition building for the 2000 Great Jubilee.[66] Aulenti used techniques similar to those in previous conversions. For example, she constructed hardboard walls to conceal utilities and create hanging space, leaving the original structure intact. Aulenti also increased the availability of natural light and the flexibility of artificial lighting.[1]

Japan

editAulenti designed the Italian Cultural Institute and the Chancellery of the Italian Embassy in Tokyo.[24] At the Italian Cultural Institute, Aulenti used a cladding coloured RAL 3011, a red-brown hue found in Japanese lacquerware. The choice was controversial due to the perceived intensity of the hue.[24]

Other selected architectural design projects

editOther projects include the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (2003), the Italian cultural institute in Tokyo (2005), the Palazzo Branciforte in Palermo, Sicily (2007) and the Perugia San Francesco d'Assisi (Umbria International Airport) for the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy (2011).[67][68] In 1991, Aulenti converted a 17th century granary at the Torrecchia Vecchia estate in Lazio to a villa for Carlo Caracciolo.[69] Aulenti also designed the Italian Pavilion at the Seville Expo '92 and the redevelopment of the Piazzale Cadorna in Milan in 2000.[25]

Stage and costume design

editAulenti and Luca Ronconi, theatre director and producer, founded the Prato Theatre design workshop (Laboratorio di Progettazione Teatrale) in the late 1970s.[70] Together, they staged 16 productions including, Pier Paolo Pasolini's Calderón, Euripides Le Baccanti, and Hugo von Hofmannsthall's La Torre.[71][72]

In her stage designs, Aulenti made reference to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's work, A Manifesto of Variety Theatre (1913). Marinetti rejected imitation of the historic and obsessive reproduction of daily life. Rather, he chose freedom in design, the use of a cinematic background, and imaginative, satiric and futuristic concepts. Aulenti did not rely on scenery canvas and flats to provide perspective. Instead, she divided the stage with structures such as platforms in order to give context to each scene.[7][1][73][74]

Aulenti created the stage design for Wozzeck (1925), the atonal opera by Alban Berg, at La Scala in 1977. Claudio Abbado was the conductor with Gloria Lane and Guglielmo Sarabia the principals.[75] Aulenti's daughter, Giovanna Buzzi, designed the costumes.[1]

The French music critic, Jacques Lonchampt reviewed the production in Le Monde. He described the stage as being enclosed by a large "crushing" wall and prison gate, and the stage itself, a conveyor belt, starting and stopping but inexorably carrying the characters towards the prison.[76]

Lonchampt wrote,

This device has the major drawback of raising the stage quite considerably and of distancing the singers from the room. The sound is lost in the flies and in the first rows, at least, the voices seem thin, without force or resonance ... unreal ... which is serious in a work with such brief tableaux, where the listener must feel the physical presence of the characters from the outset.[76]

The Italian musicologist, Massimo Mila, reviewed this production in La Stampa. He describes a construction of moving boards, which changed colour with different lights. It brought props such as a chair and table or roughly arranged blankets and mattresses to the scene. He thought the stage design was effective until the noise of some unintended movements of the device interrupted the performance.[77]

Nicholas Vitaliano, Ronconi's biographer, wrote that Aulenti and Ronconi designed a type of "stage machine", a moving surface traversing the entire stage, which was otherwise left in almost entire darkness.[78]

Aulenti's stage design for Ronconi's production of Rossini's opera, Il viaggio a Reims (Journey to Reims) at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro (1984) involved on-stage cinematic screens. Video operators filmed the performance from the stage and in real time, projected the recordings, such as close-ups of the singers, onto the screens. The operators also projected video images of a royal procession which was being filmed live on the streets outside the theatre. This video led directly to the performers entering, in procession, onto the stage, a technique which was innovative in its time.[79]

The premier of Samstag aus Licht by Karlheinz Stockhausen was produced by Ronconi for La Scala (1984).[80] La Scala was too small for the expected audience and so the production was moved to the Palazzo dello sport (the Milan sports centre).[81] In the stadium space, Aulenti and Ronconi created a spectacle. In the act, "Lucifer's dance", the "spirit of negation" appeared on stilts in front of a very large human face. The character on stilts controlled the face through the music of a wind band that was seated on a vertical frame on the stage.[82]

Aulenti also created the stage design for Elektra by Richard Strauss in Milan (1984).[1]

Exhibitions

editAulenti created stage designs for The Wild Duck by Henrik Ibsen in Genoa, the premier of Aulenti designed exhibition spaces both in Italy and abroad.[83][25]

At the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in New York City, Aulenti designed the exhibition space for the The Italian Metamorphosis 1943–1968 (1994), an exhibition of post-war art and design curated by Germano Celant. Aulenti created a large sculpture of wire triangles which projected into the museum's atrium. The visitors' perspective on the sculpture gradually changed as they walked up the ramp.[84][85] Benjamin Buchloh commented that designers, such as Aulenti, are able to highlight their own "trademark" architectural aesthetic by incorporating it into their exhibition design. He was critical, suggesting that this is to the detriment of the artistic work or object being displayed. Buchloch described Aulenti's "zig-zag" design, when placed in the curved space of the Guggenheim, as a "vagina dentata."[86]

Aulenti created exhibition designs for Futurismo and Futurismi (1986), I Fenici (1988), I Celti (1991), I Greci in Occidente (1996) and Da Puvis de Chavannes a Matisse e Picasso and Verso l'Arte Moderna (2002) at the Palazzo Grassi.[87][15][88]

The first comprehensive exhibition of Aulenti's own works was at the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, in Milan (1976), organised by fellow architect and friend, Vittorio Gregotti.[7]

Milan Triennial

editAulenti had an association with the Milan Triennial over many years.[1] She presented her own work, "Ideal apartment for an urban location" at the La casa e la scuola exhibition at the 12th Triennial in 1960.

Then, in 1964, she won the Grand International Prize for Arrivo al Mare (Arrival at the seaside). In this work, Aulenti installed a large mirrored room with multiple, life-sized, colour-sketched cut-outs of women in simple robes, standing under a ceiling of slung fabric strips. It was inspired by Pablo Picasso.[10][89]

Aulenti was a member of the executive of the Triennial from 1977 to 1980. She designed spaces for installations at exhibitions such as the 1951–2001 Made in Italy? (2001).[90]

Professional affiliations

editFrom 1955 to 1965, Aulenti was a member of the editorial staff of the design magazine, Casabella-Continuità. Aulenti wrote two articles for Casabella: Soviet architecture (1962) and Marin County (1964).[10] From 1954 to 1962, Aulenti was a member of the editorial staff of Lotus international, the quarterly Milanese architecture magazine.[6]

As an educator, Aulenti was an assistant professor of architectural composition (1960–1962) at Ca' Foscari University of Venice, adjunct assistant professor of elements of architectural composition (1964) at Milan Polytechnic, and visiting lecturer at the College of Architecture, Barcelona and the Stockholm Cultural Centre (1969–1975).[6] She also taught at the Milan School of Architecture (1964–1967).[10]

Aulenti was a member of Movimento Studi per I'Architettura, Milan (1955 - 961) and the Association for Industrial Design, Milan (1960 and vice-president in 1966).[10]

Death and legacy

editOn 31 October 2012, Aulenti died at her home in the Brera district of Milan as a result of chronic illness.[91]

Fifteen days prior, she had made her last public appearance when she received the Gold Medal for Lifetime Achievement at the Milan Triennial.[12]

Ten days after her death, Aulenti's major work to expand the Perugia San Francesco d'Assisi – Umbria International Airport was inaugurated. It was designed for the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy.[25]

In December 2012, the Piazza Gae Aulenti was dedicated to Aulenti's memory. It is a contemporary public space surrounded by private enterprises in the Isola neighbourhood near the Porta Garibaldi railway station. The piazza is 100 meters in diameter and is constructed 6 meters above ground level. There are three large fountains with a boardwalk extending to the centre of the piazza.[92]

After Aulenti's death, the Milan Triennial and Archivio Gae Aulenti created an exhibition remembering her life and work. It is a sequence of rooms recreating, true to size, several of her interior design projects, including the Arrivo al Mare room. At the centre of the exhibition is a display of Aulenti's industrial design works and around the perimeter, a display of Aulenti's papers.[90][93]

From 2020 to 2021, the Vitra Design Museum, a private museum in Germany, presented the exhibition, Gae Aulenti: A Creative Universe.[23]

For the tenth anniversary of Aulenti's death, Open House – Milan and the Aulenti estate created an exhibition highlighting Aulenti's contribution to architecture, choosing one project from each of the Open House Italia network cities: Milan (Piazza Cadorna), Naples (Piazza Dante), Rome (Scuderie del Quirinale) and Turin (Palavela).[25] In Japan, an exhibition and symposium about Aulenti's work was held on 11 December 2022.[24]

A selection of Aulenti's papers, drawings, and designs, including the design drawings for the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, California are curated at the International Archive of Women in Architecture in the Newman Library, at Virginia Tech.[94] Drawings, photographic material and design models under plexiglass by Aulenti are held by Sistema Informativo Unificato per le Soprintendenze Archivistiche (SIUSA).[95] Aulenti's granddaughter, Nina Artioli is the curator of Aulenti's archive in Milan.[24]

Architects, Marco Bifoni, Francesca Fenaroli and Vittoria Massa continue under Aulenti's name as G.A. Architetti Associati.[96]

Awards.

edit- Ubi Prize for Stage Design, Milan, 1980.[10]

- Architecture Medal, Academie d' Architecture, Paris, 1983.[10]

- Josef Hoffmann Prize, Hochschule fur Angewandte Kunst, Vienna, 1984.[10]

- Commandeur, Order des Artes et Letters, France,1987.[10]

- Honorary Dean of Architecture, Merchandise Mart of Chicago, 1988.[10]

- Accademico Nazionale, Accademia di San Luca, Rome, 1988.[10]

- Premio speciale della cultura, Repubblica Italiana X Legislatura, 1989.[97]

- Praemium Imperiale, Japan, 1991.[98][24]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Petranzan, Margherita (1996). Gae Aulenti. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-2059-9.

- ^ a b c d Guerrand, Roger-Henri (2015-10-27). Dictionnaire des Architectes: Les Dictionnaires d'Universalis (in French). Encyclopaedia Universalis. ISBN 978-2-85229-141-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Colquhoun, Alan (2002-04-25). Modern Architecture. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-159264-5.

- ^ Seražin, Helena; Garda, Emilia Maria; Franchini, Caterina (2018-06-13). Women's Creativity since the Modern Movement (1918-2018): Toward a New Perception and Reception. Založba ZRC. ISBN 978-961-05-0106-0.

- ^ a b Sabini, Maurizio (2021-02-11). Ernesto Nathan Rogers: The Modern Architect as Public Intellectual. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-11742-6.

- ^ a b c Emanuel, Muriel (2016-01-23). Contemporary Architects. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-04184-8.

- ^ a b c Gregotti, Vittorio (1986-04-09). "BUILDING A PASSAGE". Artforum. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ Lacy, Bill (1991). 100 Contemporary Architects: Drawings & Sketches. H.N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3661-4.

- ^ a b Martin, Douglas (2012-11-02). "Gae Aulenti, Musée d'Orsay Architect, Dies at 84". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hillstrom, Laurie Collier (1999). Contemporary Women Artists. USA: St. James Press. pp. 39. ISBN 1-55862-372-8.

- ^ "Le onorificenze della Repubblica Italiana". Presidenza della Repubblica. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hartman, Jan Cigliano (2022-03-29). The Women Who Changed Architecture. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-64896-086-4.

- ^ Briganti, Annarita (2022-09-20). Gae Aulenti (in Italian). Cairo. ISBN 978-88-309-0275-6.

- ^ "Story Gae Aulenti". Storie Milanesi. Retrieved 2024-08-28.

- ^ a b "Biografia | Archivio Gae Aulenti" (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Wainwright, Oliver (5 November 2012). "Gae Aulenti obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Keshmiry, Mariama (2020-09-17). "News | People in design. Farewell to architect and designer Cini Boeri". ndion. Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ Groot, Marjan; Seražin, Helena; Garda, Emilia Maria; Franchini, Caterina (2017-09-01). MoMoWo. Women designers, craftswomen, architects and engineers between 1918 and 1945. Založba ZRC. ISBN 978-961-05-0033-9.

- ^ a b c admin (2021-04-04). "Giovanna Buzzi". Alain Elkann Interviews. Retrieved 2024-09-07.

- ^ Strauss, Cindi (2020-02-25). Radical: Italian Design 1965-1985 : the Dennis Freedman Collection. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24749-7.

- ^ A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ^ "Sgarsul, Gae Aulenti's debut as a designer". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ a b c "Gae Aulenti: A Creative Universe". www.design-museum.de (in German). Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Belfiore, Matteo (25 December 2022). "Gae Aulenti – A look at Japan and the world". ADF Web Magazine. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e "Gae Aulenti. City open artwork – Auic". www.auic.polimi.it. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Architetti senza tempo, Gae Aulenti. Città opera aperta". Eventi del Politecnico di Milano. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti. Vitra Design Museum". ITSLIQUID. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ a b Schleuning, Sarah; Strauss, Cindi; Horne, Sarah; MacLeod, Martha; Perkins, Berry Lowden (2021-01-01). Electrifying Design: A Century of Lighting. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25457-0.

- ^ Service, Customer (2023-04-18). "Jacquemus + Exteta, a new take on Locus Solus – EXTETA". exteta.it. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ "Poltronova: Italian Radical Design". artemest.com. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ Colbachini, Francesco (2023-11-23). "The Locus Solus Series". Italian Design Club. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ Tamm, Marek; Olivier, Laurent (2019-08-22). Rethinking Historical Time: New Approaches to Presentism. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-06510-9.

- ^ a b "Pipistrello: (story of) a light turned icon". DesignBest magazine (Website) (in Italian). 25 April 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Pipistrello – Martinelli Luce Website". martinelliluce.it. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti La Ruspa Lamp by Gae Aulenti for Martinelli Luce, Italy, 1968". Castorina. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti and Olivetti". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti and Olivetti". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ Gavinelli, Corrado; Loik, Mirella (1993). Architettura del XX secolo (in Italian). Editoriale Jaca Book. ISBN 978-88-16-43911-5.

- ^ a b "Vitra Design Museum: Collection". collectiononline.design-museum.de. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti | Knoll". www.knoll.com. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "A Future Icon: The Louis Vuitton Monterey Deisgned By Gae Aulenti In 1988 – Italian Watch Spotter". 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ a b Creating the MusŽe d'Orsay: The Politics of Culture in France. Penn State Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-271-03834-6.

- ^ a b c Winchip, Susan (2014-02-07). Visual Culture in the Built Environment: A Global Perspective. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-62892-450-3.

- ^ "Musee D'Orsay, Paris". World Construction Network. Retrieved 2024-08-29.

- ^ Ames, David L.; Wagner, Richard D. (2009). Design & Historic Preservation: The Challenge of Compatibility : Held at Goucher College, Baltimore, Maryland, March 14-16, 2002. Associated University Presse. ISBN 978-0-87413-831-3.

- ^ Barker, Emma; Barker, Senior Lecturer in Art History Emma (1999-01-01). Contemporary Cultures of Display. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07783-4.

- ^ LTD, DESIGN MUSEUM ENTERPRISE; Fitoussi, Brigitte; Fortes, Imogen (2017-03-09). Paris in Fifty Design Icons. Octopus. ISBN 978-1-84091-756-7.

- ^ a b Jencks, Charles (2012-05-25). The Story of Post-Modernism: Five Decades of the Ironic, Iconic and Critical in Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-96009-6.

- ^ Rattenbury, Kester (2005-08-04). This is Not Architecture: Media Constructions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56766-9.

- ^ "Musée d'Orsay". museums.eu. Retrieved 2024-08-29.

- ^ Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris: An Architectural Guide. Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 978-3-930698-96-7.

- ^ Barker, Emma; Barker, Senior Lecturer in Art History Emma (1999-01-01). Contemporary Cultures of Display. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07782-7.

- ^ Milojovic A. and Nikolic M. Museum architecture and conversion: From paradigm to institutionalization of anti-museum. Facta universitatis - series Architecture and Civil Engineering. Jan 2012, 10(1):77

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (2 April 1987). "Architecture: the new Mussee D'orsay in Paris". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Center Georges Pompidou, a 1985 project by Piero Castiglioni as a lighting designer". Marco Petrucci. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ "Our building – Centre Pompidou". Centre Pompidou. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Paris architectural masterpiece. Center Pompidou by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers | METALOCUS". www.metalocus.es. 2021-12-19. Retrieved 2024-08-29.

- ^ Pile, John; Gura, Judith; Plunkett, Drew (2024-01-17). A History of Interior Design. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-63886-5.

- ^ Weston, Richard (2004). Plans, Sections and Elevations: Key Buildings of the Twentieth Century. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-382-0.

- ^ a b "Palazzo Grassi. Art Destination Venice". universes.art. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ "Neoclassicism in Venice: Grassi Palace, extraordinary museum, residence of a ghost". visitvenezia.eu. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Scala, Quin (2017-04-01). Lighting: 20th Century Classics. Fox Chapel Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60765-395-0.

- ^ Arduini C. Palazzo Grassi in Venice Maire Tecnimont Foundation. https://fondazione.groupmaire.com/media/filer_public/04/cd/04cd5ae4-893f-4d61-853f-bde3ac829fc1/palazzo-venice-min.pdf Accessed 30 August 2024

- ^ a b Strum, Suzanne (2001). Barcelona: A Guide to Recent Architecture. Ellipsis. ISBN 978-1-84166-005-9.

- ^ "Expo Barcelona 1929 | National Palace | Central area". en.worldfairs.info. Retrieved 2024-09-10.

- ^ "Scuderie del Quirinale". Ales Arte Lavoro e Servizi S.p.A. (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "Palace". Palazzo Branciforte. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ Internazionale, Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione. "Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Tokyo". iictokyo.esteri.it (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-09-02.

- ^ "Torrecchia Vecchia – English Gardens hidden in the Lazio". Torrecchia Vecchia. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ Woodham, Jonathan (2016-05-19). A Dictionary of Modern Design. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-251853-8.

- ^ "Tutti i risultati conGae Aulenti - Luca Ronconi". lucaronconi.it. Retrieved 2024-09-07.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti, biografia e mostre". Itinerari nell'Arte. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ Marinetti F.T. A Manifesto of Variety Theatre (1913) chapter 13. Variety Theatre pages 126–127. https://writingstudio2010.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/variety-stage.pdf Accessed 8 September 2024.

- ^ Marrone, Gaetana; Puppa, Paolo (2006-12-26). Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45530-9.

- ^ Lotti, Giorgio; Radice, Raul (1979). La Scala. Elm Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-241-10329-6.

- ^ a b "À LA SCALA DE MILAN Le " Wozzeck " désincarné de Ronconi" (in French). 1977-04-19. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- ^ Mila, Massimo (2012-06-08). Mila alla Scala (in Italian). Bur. ISBN 978-88-586-2969-7.

- ^ Vitaliano, Nicholas (2021-07-29). Il lavoro teatrale di Luca Ronconi: Gli anni del piccolo (in Arabic). Mimesis. ISBN 978-88-575-8315-0.

- ^ Quazzolo, Paolo (2022-07-31). Rappresentazioni e tecniche della visione (in Italian). Marsilio Editori spa. ISBN 978-88-297-1691-3.

- ^ Gregori, Maria (24 May 1984). "Dio c'e e lo metto in musica" [God is there and I put it to music] (PDF). L'Unita (in Italian). p. 14. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Obst J. (trans.) Saturday from Light. (1984). Dialogue transcribed from the WDR film for Saturday World Theatre. https://www.stockhausen-verlag.com/DVD_Translations/19_Saturday_World_Theatre.pdf Accessed 17 September 2024.

- ^ Parker, Roger (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285445-2.

- ^ "A nomadic exhibition by Gae Aulenti for Olivetti in 1970". www.domusweb.it. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "9 Times Architects Transformed Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum". ArchDaily. 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ "Nine Guggenheim Exhibitions Designed by Architects". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. (1995-01-01). "Focus: "The Italian Metamorphosis, 1943–1968"". Artforum. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ Quinn, Josephine Crawley; Vella, Nicholas C. (2014-12-04). The Punic Mediterranean: Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-19493-5.

- ^ Quinn, Josephine Crawley; Vella, Nicholas C. (2014-12-04). The Punic Mediterranean: Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-19493-5.

- ^ Scrivano, Paolo (2017-05-15). Building Transatlantic Italy: Architectural Dialogues with Postwar America. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-17082-2.

- ^ a b "Gae Aulenti (1927–2012)". triennale.org. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (2012-11-05). "Gae Aulenti Dies, Age 84". ARTnews. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Massetti, Enrico (2015-08-21). Milan. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-329-49693-4.

- ^ Todd, Laura M. (2024-05-31). "Pioneering designer Gae Aulenti's illustrious career is celebrated in a new Milan retrospective". wallpaper.com. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ "A Guide to the Gae Aulenti Architectural Collection, 1987–2003 Aulenti, Gae, Architectural Collection Ms2000-014". ead.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ "SIUSA – Aulenti Gae". siusa-archivi.cultura.gov.it. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Chi siamo". aulenti-associati (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Il presidente del consiglio Ciriaco De Mita assegna i Premio speciale della cultura – Auletta dei gruppi: 9 marzo 1989 / Archivio fotografico / Camera dei deputati – Portale storico". storia.camera.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-09-02.

- ^ "Gae Aulenti | The official website of the Praemium Imperiale". 高松宮殿下記念世界文化賞. Retrieved 2024-09-02.

Further reading

edit- Emmanuel, M. (1980). Contemporary Architects. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-312-16635-4. NA680.C625.

- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

- Peltason, Ruth A. (1991). 100 Contemporary Architects. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 0-8109-3661-5. NA2700.L26.

- "Gae Aulenti". Design & Art. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011.

- Davide Mosconi. "Design Italia '70" Milan 1970.

- Nathan H. Shapira, "Design Processes Olivetti 1908–1978". Los Angeles, 1979.

- Vittorio Gregotti, Emilio Battisti, Franco Quadri. "Gae Aulenti" exhibition catalog. Milan 1979.

- Erica Brown, "Interior Views" London 1980

- Eric Larrabee, Massimo Vignelli, "Knoll Design", New York 1981.

- "Gae Autenti e il Museo d' Orsay" Milan 1987.

- Arata Isozaki "International Design Yearbook 1988–89", London 1988.

- Marc Gaillard, Oeil Magazine, November 1990.

- Jeremy Myerson, "Grande Dame" article in Design Week, 14 October 1994.

- "Pillow Talk" article in Design Week, 10 November 1995.

- "Gae Aulenti : Weekend House for Mrs. Brion, San Michele, Italy, 1974." GA Houses, no. 171 (July 1, 2020): 67–69.

- Rykwert, Joseph, 1926–. "Gae Aulenti’s Milan." Architectural Digest 47, no. 1 (January 1, 1990): 92–97.

External links

edit- Aulenti's Legacy – Triennale di Milano – a documentary podcast hosted by Alice Rawsthorn (5 episodes)

- Aulenti: A Creative Universe – a video about the Vitra Design Museum exhibition tour.

- Aulenti open house - Fontana-arte 2022 In 2022, Aulenti's home was opened to the public.