The examples and perspective in this dog-centric article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2024) |

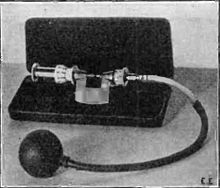

A dog whistle (also known as silent whistle or Galton's whistle) is a type of whistle that emits sound in the ultrasonic range, which humans cannot hear but some other animals can, including dogs and domestic cats, and is used in their training. It was invented in 1876 by Francis Galton and is mentioned in his book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development,[1] in which he describes experiments to test the range of frequencies that could be heard by various animals, such as a house cat.

The upper limit of the human hearing range is about 20 kilohertz (kHz) for children, declining to 15–17 kHz for middle-age adults.[2] The top end of a dog's hearing range is about 45 kHz, while a cat's is 64 kHz.[3][4] It is thought that the wild ancestors of cats and dogs evolved this higher hearing range in order to hear high-frequency sounds made by their preferred prey, small rodents.[3] The frequency of most dog whistles is within the range of 23 to 54 kHz,[5] so they are above the range of human hearing, although some are adjustable down into the audible range.

To human ears, dog whistles only emit a quiet hissing sound.[6] The principal advantage of dog whistles is that they do not produce a loud, potentially irritating noise for humans that a normal whistle would produce and thus can be used to train or command animals without disturbing nearby people. Some dog whistles have adjustable sliders for active control of the frequency produced. Trainers may use the whistle simply to get a dog's attention or to inflict pain for the purpose of behaviour modification.

In addition to lung-powered whistles, there are also electronic dog whistle devices that emit ultrasonic sound via piezoelectric emitters.[3] The electronic variety are sometimes coupled with bark-detection circuits in an effort to curb barking behaviour. This kind of whistle can also be used to determine the hearing range for people and for physics demonstrations requiring ultrasonic sounds.[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Galton, Francis (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, pp. 26-27.

- ^ D'Ambrose, Christoper; Choudhary, Rizwan (2003). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Frequency range of human hearing". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ^ a b c Krantz, Les (2009). Power of the Dog: Things Your Dog Can Do That You Can't. MacMillan. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-0312567224.

- ^ Strain, George M. (2010). "How Well Do Dogs and Other Animals Hear?". Prof. Strain's website. School of Veterinary Medicine, Louisiana State University. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Caroline Coile, D.; Bonham, Margaret H. (2008), "Why Do Dogs Like Balls?: More Than 200 Canine Quirks, Curiosities, and Conundrums Revealed", Sterling Publishing Company, Inc: 116, ISBN 9781402750397, retrieved 2011-08-07

- ^ Weisbord, Merrily; Kachanoff, Kim (2000). Dogs with Jobs: Working Dogs Around the World. Simon & Schuster. pp. xvi–xvii. ISBN 0671047353.

External links

edit- Media related to Dog whistles at Wikimedia Commons