Gavin Douglas (c. 1474 – September 1522) was a Scottish bishop, makar and translator. Although he had an important political career, he is chiefly remembered for his poetry. His main pioneering achievement was the Eneados, a full and faithful vernacular translation of the Aeneid of Virgil into Scots, and the first successful example of its kind in any Anglic language. Other extant poetry of his includes Palice of Honour, and possibly King Hart.

Gavin Douglas | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Dunkeld | |

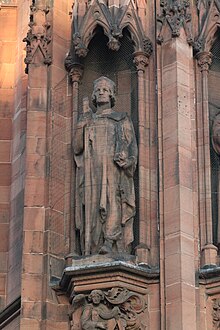

Statue of Gavin Douglas, Scottish National Portrait Gallery | |

| See | Diocese of Dunkeld |

| In office | 1515/6 – 1522 |

| Predecessor | Andrew Stewart |

| Successor | Robert Cockburn |

| Previous post(s) | Provost of St. Giles' |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 1516 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1474 Tantallon Castle, East Lothian |

| Died | September 1522 London |

| Nationality | Scottish |

Life and career

editEarly life

editGavin (or Gawin, Gawane, Gawain) Douglas was born c. 1474–76, at Tantallon Castle, East Lothian, the third son of Archibald, 5th Earl of Angus by his second wife Elizabeth Boyd. A Vatican register records that Gavin Douglas was 13 in 1489, suggesting he was born in 1476. An application had been lodged to award Gavin the right to hold a Church canonry or prebend and enjoy its income. Another appeal to Rome concerning church appointments made in February 1495 states his age as 20.[1]

He was a student at St Andrews University in 1489–94, and thereafter, it is supposed, at Paris.[2] He chiefly studied Aristotle's Logic, Physics, Natural Philosophy, and Metaphysics.[3] in 1492 he received his bachelor's degree, and in 1496 was named among the Licentiati, or Masters of Arts, which was regarded at the time as an advanced academic degree.[3] In 1496 he obtained the living of Monymusk, Aberdeenshire, and later he became parson of Lynton (modern East Linton) and rector of Hauch (modern Prestonkirk), in East Lothian. About 1501 he was preferred to the deanery or provostship of the collegiate church of St Giles, Edinburgh, which he held with his parochial charges.[4]

Early career

editUntil the Battle of Flodden in September 1513, Gavin Douglas appears to have been occupied with his ecclesiastical duties and literary work. Indeed, all the extant writings by which he has earned his place as a poet and translator belong to this period. After the disaster at Flodden he was completely absorbed in public business.

Before the crisis of 1513, Douglas was a friend and correspondent of many of the internationally renowned men of his age, including Polydore Vergil, John Major, Cardinal Wolsey and Henry, 3rd Lord Sinclair. Because of his powerful family connections and role in high public life, he is the best-documented of the early Scottish makars. Indeed, of poets in the British Isles before him, only the biography of Chaucer is as well documented or understood. All his literary work was composed before his 40th year while he was Provost of St Giles in Edinburgh. Douglas's literary work was composed in a highly polished Middle Scots, often aureate in style. After the Eneados he is not known to have produced any further poetry, despite being at the height of his artistic powers when it was completed in 1513, six weeks before the Battle of Flodden. No more than four of works by him are known to exist; The Palice of Honour, Conscience, his major translation the Eneados, and possibly King Hart.

While Provost of St Giles, in 1510 Gavin applied to the Pope for permission to celebrate the marriages of couples who were related within the limits and degrees proscribed by the Church. Gavin argued that these marriages helped to make peace in Scotland, and the long delay in receiving a dispensation from Rome in each case, which was a formality, was inconvenient and unnecessary. Gavin asked to be allowed to conduct ten such marriages over four years.[5]

Career during the minority of James V

editAfter the Battle of Flodden, during the minority of James V of Scotland, the Douglas family assumed a pivotal role in public affairs. Three weeks after the Battle of Flodden Gavin Douglas, still Provost of St Giles, was admitted a burgess of Edinburgh. His father, the "Great Earl", was then the civil provost of the capital. The Earl died soon afterwards in January 1514 in Wigtownshire, where he had gone as justiciar. As his son had been killed at Flodden, the succession fell to Gavin's nephew, Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus.

The marriage of the young Earl of Angus to James IV's widow, Margaret Tudor, on 6 August 1514 did much to identify the Douglases with the English party in Scotland, as against the French party led by the Duke of Albany, and incidentally to determine the political career of his uncle Gavin. During the first weeks of the Queen's sorrow after the battle, Gavin, with one or two colleagues of the council, acted as personal adviser, and it may be taken for granted that he supported the pretensions of the young earl. His own hopes of preferment had been strengthened by the death of many of the higher clergy at Flodden.

The first outcome for Gavin from the new family connection was his appointment to the Abbacy of Aberbrothwick by the Queen Regent, as Margaret Tudor was before her marriage, probably in June 1514. Soon after the marriage of Angus to Margaret she nominated him Archbishop of St Andrews, in succession to William Elphinstone, archbishop-designate. But John Hepburn, prior of St Andrews, having obtained the vote of the chapter, expelled him, and was himself in turn expelled by Andrew Forman, Bishop of Moray, who had been nominated by the Pope. In the interval, Douglas's rights in Aberbrothwick had been transferred to James Beaton, Archbishop of Glasgow, and he was now without title or temporality. The breach between the Queen's party and Albany's had widened, and the Queen's advisers had begun an intrigue with England, to the end that the royal widow and her young son should be removed to Henry's court. In those deliberations Gavin Douglas took an active part, and for this reason stimulated the opposition which successfully thwarted his preferment.

Gavin Douglas became heavily involved in affairs of state, seeking a dominant role as one of the Lords of Council and bidding to attain one or more of the many sees, including the archbishopric of St Andrews, left vacant in the destructive aftermath of the Scottish defeat. He finally obtained the bishopric of Dunkeld in 1516, but only after a bitter struggle.

In 1517, in his more settled public position, Douglas was one of the leading members of the embassy to Francis I which negotiated the Treaty of Rouen, but his role in the volatile politics of the period, mainly centring on control over the minority of James V, was deeply contentious. By late 1517 he had managed to earn the enduring hostility of the Queen Mother, a former ally, and in subsequent years became manifestly involved in political manœuvring against the Regent Albany. At the same time he remained ambitious for the St Andrews archbishopric, which fell vacant once again in 1521. His career was cut short when he died suddenly during a brief period in exile in London.

Bishop of Dunkeld

editIn January 1515 on the death of George Brown, Bishop of Dunkeld, Douglas's hopes revived. The queen nominated him to the now vacant seat, which he ultimately obtained, though not without trouble. For John Stewart, 2nd Earl of Atholl had forced his brother, Andrew Stewart, prebendary of Craig, upon the chapter, and had put him in possession of the bishop's palace. The queen appealed to the pope and was seconded by her brother of England, with the result that the Pope's sanction was obtained on 18 February 1515. Some of the correspondence of Douglas and his friends incident to this transaction was intercepted. When Albany came from France and assumed the regency, these documents and the "purchase" of the bishopric from Rome contrary to statute were made the basis of an attack on Douglas, who was imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle, thereafter in St Andrews Castle (under the charge of his old opponent, Prior Hepburn), and later in Dunbar Castle, and again in Edinburgh. Papal intervention procured his release after nearly a year's imprisonment. The Queen, meanwhile, had retired to England. After July 1516 Douglas appears to have been in possession of his see and to have patched up a diplomatic peace with Albany.

On 17 May 1517 the Bishop of Dunkeld proceeded with Albany to France to conduct the negotiations which ended in the Treaty of Rouen. He was back in Scotland towards the end of June. Albany's longer absence in France permitted the party faction of the nobles to come to a head in a plot by James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran to seize the Earl of Angus, the Queen's husband. The issue of this plot was the well-known fight of Cleanse the Causeway, in which Gavin Douglas's part stands out in picturesque relief. The triumph over the Hamiltons had an unsettling effect upon the Earl of Angus. He made free with the Queen's rents and abducted Lord Traquair's daughter. The Queen set about obtaining a divorce and used her influence for the return of Albany as a means of undoing her husband's power. Albany's arrival in November 1521, with a large body of French men-at-arms, compelled Angus, with the bishop and others, to flee to the Borders. From this retreat Gavin Douglas was sent by the earl to the English court, to ask for aid against the French party and against the Queen, who was reported to be the mistress of the Regent. Meanwhile, Douglas was deprived of his bishopric and forced, for safety, to remain in England, where he effected nothing in the interests of his nephew. The declaration of war by England against Scotland, in answer to the recent Franco-Scottish negotiations, prevented his return. His case was further complicated by the libellous animosity of James Beaton, Archbishop of Glasgow (whose life he had saved in the "Cleanse the Causeway" incident), who was anxious to put himself forward and thwart Douglas in the election to the archbishopric of St Andrews, left vacant by the death of Forman.

Death

editIn 1522 Douglas was stricken by the plague which raged in London, and died at the house of his friend Lord Dacre. During the closing years of exile he was on intimate terms with the historian Polydore Vergil, and one of his last acts was to arrange to give Polydore a corrected version of Major's account of Scottish affairs. Douglas was buried in the church of the Savoy, where a monumental brass (removed from its proper site after the fire in 1864) still records his death and interment.

For Douglas's career see, in addition to the public records and general histories, John Sage's Life in Thomas Ruddiman's edition, and that by John Small in the first volume of his edition The Poetical Works of Gavin Douglas (1874).

Memorials

editA Victorian brass plaque to Douglas exists in St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh (placed on one of the southern columns).

There is a bin commemorating Gavin Douglas in Queen's Park, Glasgow.

Works

editPalice of Honour

editThe Palice of Honour, dated 1501, is a dream-allegory extending to over 2000 lines, composed in nine-line stanzas. It is his earliest work. In its descriptions of the various courts on their way to the palace, and of the poet's adventures – first, when he incautiously slanders the court of Venus, and later when after his pardon he joins in the procession and passes to see the glories of the palace – the poem carries on the literary traditions of the courts of love, as shown especially in the "Romaunt of the Rose" and "The Hous of Fame". The poem is dedicated to James IV, not without some lesson in commendation of virtue and honour.

No manuscript of the poem is extant. The earliest surviving edition (c. 1553) was printed at London by William Copland (died 1569). An Edinburgh edition, from the press of Henry Charteris (died 1599), followed in 1579. From certain indications in the latter and the evidence of some odd leaves discovered by David Laing, it has been concluded that there was an earlier Edinburgh edition, which has been ascribed to Thomas Davidson, printer, and dated c. 1540.

Eneados

editDouglas's major literary achievement is the Eneados, a Scots translation of Virgil's Aeneid, completed in 1513, and the first full translation of a major poem from classical antiquity into any modern Germanic language. His translation, which is faithful throughout, includes the 13th book by Mapheus Vegius. Each of the 13 books is introduced additionally by an original verse prologue. These deal with various matters, sometimes semi-autobiographical, in a variety of styles.

Other accredited works

editTwo other poems are accredited to Gavin Douglas, King Hart and Conscience.

Conscience is a short four-stanza poem. Its subject is the "conceit" that men first clipped away the "con" from "conscience" to leave "science" and "na mair"; then they lost "sci" and had nothing but "ens": that schrew, Riches and geir.

King Hart is a poem of doubtful accreditation.[6] Like The Palice of Honor, it is a later allegory, and as such, of high literary merit. Its subject is human life told in the allegory of King Hart (Heart) in his castle, surrounded by his five servitors (the senses), Queen, Plesance, Foresight and other courtiers. The poem runs to over 900 lines and is written in eight-line stanzas. The text is preserved in the Maitland folio manuscript in the Pepysian library, Cambridge. It is not known to have been printed before 1786, when it appeared in Pinkerton's Ancient Scottish Poems.

Modern editions

edit- Gavin Douglas's Translation of the Aeneid, edited by Gordon Kendal, 2 volumes, London, MHRA, 2011

- Virgil's Aeneid translated into Scottish Verse by Gavin Douglas, Bishop of Dunkeld, edited by David F.C. Coldwell, 4 Volumes, Edinburgh, Blackwood for The Scottish Text Society, 1957–64

- Gavin Douglas: A selection from his Poetry, edited by Sydney Goodsir Smith, Edinburgh, Oliver & Boyd for The Saltire Society, 1959

- Selections from Gavin Douglas, edited by David F. C. Coldwell, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1964

- The Shorter Poems of Gavin Douglas, edited by Priscilla J Bawcutt, Edinburgh, Blackwood for The Scottish Text Society, 1967 (reprint 2003)

- The palis of honoure [by] Gawyne Dowglas, Amsterdam, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum; New York, Da Capo Press, 1969

- The Palyce of Honour by Gavin Douglas, edited by David J. Parkinson, 2nd edition, Michigan, Medieval Institute Publications, 2018.

- The Makars: the poems of Henryson, Dunbar, and Douglas, edited, introduced, and annotated by J.A. Tasioulas, Edinburgh, Canongate Books, 1999

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ Bawcutt 1994, pp. 95–96. (Bawcutt is unclear about whether these are "old style" dates.) The 1495 register refers to Douglas as a Glasgow M.A., which may mark a confusion with a namesake, Gavin Douglas, son of the Laird of Drumlanrig.

- ^ Bayne, Thomas Wilson (1888). "Douglas, Gawin". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 15. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ a b "The Palyce of Honour: Introduction | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Balfour Paul, vol 1, p. 185.

- ^ Bawcutt 1994, p. 98.

- ^ Preston, Priscilla (1959). "Did Gavin Douglas Write 'King Hart'?". Medium Ævum. 28 (1): 31–47. doi:10.2307/43626771. ISSN 0025-8385. JSTOR 43626771.

Sources

edit- Balfour Paul, Sir James (1904). Scots Peerage. 9 vols. Edinburgh: David Douglas.

- Bawcutt, Priscilla (1976). Gavin Douglas: A Critical Study. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.

- ——— (1994). "New Light on Gavin Douglas". In MacDonald, A. A.; Lynch, Michael; Cowan, Ian B. (eds.), The Renaissance in Scotland. Leiden: Brill. pp. 95–106.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Douglas, Gavin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 444–445. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Further reading

edit- Ellis, Henry, ed., Original Letters Illustrative of English History, 3rd Series, vol. 1 (London: Richard Bentley, 1846), pp. 293–303. Letters from Douglas to Cardinal Wolsey.

- Hubbard, Tom (1991), "Chosyn Carbukkill: Virgil's Northern Legacy", in Hubbard, Tom (2022), Invitation to the Voyage: Scotland, Europe and Literature, Rymour, pp. 13–16, ISBN 9-781739-596002

- Maxwell, Sir Herbert. A History of the House of Douglas. 2 vols. (London: Freemantle, 1902)

- Nicholson, Ranald. Scotland: The Later Middle Ages (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1978)