The Graf Zeppelin-class aircraft carriers were four German Kriegsmarine aircraft carriers planned in the mid-1930s by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder as part of the Plan Z rearmament program after Germany and Great Britain signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. They were planned after a thorough study of Japanese carrier designs. German naval architects ran into difficulties due to lack of experience in building such vessels, the realities of carrier operations in the North Sea and the lack of overall clarity in the ships' mission objectives.

Aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft, Deutsche Werke |

| Planned |

|

| Completed | 0 |

| Cancelled | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Aircraft carrier |

| Displacement | 33,550 tonnes |

| Length | 262.5 m (861 ft 3 in) |

| Beam | 31.5 m (103 ft 4 in) |

| Draft | 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in) |

| Propulsion | Geared turbines, 200,000 hp (150,000 kW), four screws |

| Speed | 35 knots (65 km/h) |

| Range | 14,816 km (8,000 nmi) at 19 knots (35 km/h) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Aircraft carried |

|

This lack of clarity led to features such as cruiser-type guns for commerce raiding and defense against British cruisers, that were either eliminated from or not included in American and Japanese carrier designs. American and Japanese carriers, designed along the lines of task-force defense, used supporting cruisers for surface firepower, which allowed flight operations to continue without disruption and reduced the chances of exposure to risks that surface action would have entailed.

A combination of political infighting between the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe, disputes within the ranks of the Kriegsmarine itself and Adolf Hitler's waning interest all conspired against the carriers. A shortage of workers and materials slowed construction still further and, in 1939, Raeder reduced the number of ships from four to two. Even so, the Luftwaffe trained its first unit of pilots for carrier service and readied it for flight operations. With the advent of World War II, priorities shifted to U-boat construction; one carrier, Flugzeugträger B, was broken up on the slipway while work on the other, Flugzeugträger A (christened Graf Zeppelin) was continued tentatively but suspended in 1940. The air unit scheduled for her was disbanded at that time.

The role of aircraft in the Battle of Taranto, the pursuit of the German battleship Bismarck, the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway demonstrated conclusively the usefulness of aircraft carriers in modern naval warfare. With Hitler's authorization, work resumed on the remaining carrier. Progress was again delayed, this time by the demand for newer planes specifically designed for carrier use and the need for modernizing the ship in light of wartime developments. Hitler's disenchantment with the performance of the Kriegsmarine's surface units led to a final stoppage of work. The ship was captured by the Soviet Union at the end of the war and sunk as a target ship in 1947.

Design and construction

editAfter 1933, the Kriegsmarine began to examine the possibility of building an aircraft carrier.[1] Wilhelm Hadeler had been Assistant to the Professor of Naval Construction at the Technische Hochschule in Charlottenburg (now Technische Universität Berlin) for nine years when he was appointed to draft preliminary designs for an aircraft carrier in April 1934.[2] Hadeler's first design was a 22,000-long-ton (22,000 t) ship that could carry 50 aircraft and steam at 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph).[1]

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement, signed on 18 June 1935, allowed Germany to construct aircraft carriers with total displacement up to 38,500 tons,[3] though Germany was limited to 35% of total British tonnage in any category of warship. The Kriegsmarine then decided to scale back Hadeler's design to 19,250 long tons (19,560 t), which would permit the construction of two ships within the 35% limit.[1]

The design staff decided that the new carrier would need to be able to defend itself against surface combatants, which necessitated armor protection to the standard of a heavy cruiser. A battery of sixteen 15 cm (5.9 in) guns were deemed sufficient to defend the ship from destroyers.[4] In 1935, Adolf Hitler announced that Germany would construct aircraft carriers to strengthen the Kriegsmarine. A Luftwaffe officer, a naval officer, and a constructor visited Japan in the autumn of 1935 to obtain flight deck equipment blueprints and inspect the Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi.[5] The Germans also unsuccessfully attempted to examine the British carrier HMS Furious.[6]

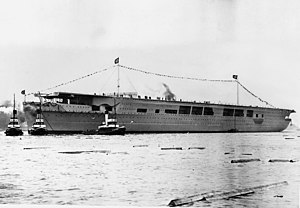

The keel of Graf Zeppelin was laid down on 28 December 1936,[1] on the slipway that had recently held the battleship Gneisenau.[6] The ship was built by the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel.[7] Two years later, Großadmiral (Grand Admiral) Erich Raeder presented an ambitious shipbuilding program called Plan Z which would build up the Kriegsmarine to a point where it could challenge the British Royal Navy in the North Sea. Under Plan Z, by 1945 as part of the balanced force the navy would have four carriers; the pair of Graf Zeppelin-class ships were the first two in the plan. Hitler approved the construction program on 1 March 1939.[8] In 1938, a second carrier, ordered under the provisional name "B", was laid down at the Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel.[9] Graf Zeppelin was launched on 8 December 1938.[10]

Design

editHull

editThe Graf Zeppelin class's hull was divided into 19 watertight compartments, the standard division for all capital ships in the Kriegsmarine.[11] Their belt armor was to vary from 100 mm (3.9 in) over the machinery spaces and aft magazines, to 60 mm (2.4 in) over the forward magazines and tapered down to 30 mm (1.2 in) at the bows. Stern armor was kept at 80 mm (3.1 in) to protect the steering gear. Inboard of the main armor belt was a 20 mm (0.79 in) anti-torpedo bulkhead.[12]

Horizontal armor protection against aerial bombs and plunging shellfire started with the flight deck, which acted as the main strength deck. The armor was generally 20 mm (0.79 in) thick except for those areas around the elevator shafts and funnel uptakes where thickness increased to 40 mm (1.6 in) in order to give the elevators necessary structural strength and the critical uptakes greater splinter protection.[12] Beneath the lower hangar was the main armored deck (or tween deck) where armor thickness varied from 60 mm (2.4 in) over the magazines to 40 mm (1.6 in) over the machinery spaces. Along the peripheries, it formed a 45 degree slope where it joined the lower portion of the waterline belt armor.[12]

The Graf Zeppelins' original length-to-beam ratio was 9.26:1, resulting in a slender silhouette. However, in May 1942, the accumulating top-weight of recent design changes required the addition of deep bulges to each side of Graf Zeppelin's hull, decreasing that ratio to 8.33:1 and giving her the widest beam of any carrier designed prior to 1942.[13] The bulges served mainly to improve Graf Zeppelin's stability but they also gave her an added degree of anti-torpedo protection and increased her operating range because selected compartments were designed to store approximately 1500 additional tons of fuel oil.[14]

Graf Zeppelin's straight-stemmed prow was rebuilt in early 1940 with the addition of a more sharply angled "Atlantic prow", intended to improve overall seakeeping. This added 5.2 m (17 ft) to her overall length.[11]

Machinery

editThe Graf Zeppelin class's power plant was to consist of 16 La Mont high-pressure boilers, similar to those used in the Admiral Hipper-class heavy cruisers. Their four sets of geared turbines, connected to four shafts, were expected to produce 200,000 shp (150,000 kW) and propel the carrier at a top speed of 35 knots (40 mph; 65 km/h). With a maximum bunkerage capacity of 5000 tons of fuel oil (prior to the addition of bulges in 1942), the Graf Zeppelins' calculated radius of action was 9,600 miles (15,400 km) at 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). However, wartime experience on ships with similar power plants showed such estimates were highly inaccurate, and actual operational ranges tended to be much lower.[15]

Two Voith-Schneider cycloidal propeller-rudders were to be installed in the forward bow of the ship along the center-line. These were intended to assist in berthing the ship in harbor and also in negotiating narrow waterways such as the Kiel Canal where, due to the carrier's high freeboard and difficulty in maneuvering at speeds below 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), gusting winds might push the ship into the canal sides. In an emergency, the units could have been used to steer the ships at speeds under 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) and, if the ships' main engines were rendered inoperable, could propel the vessel at a speed of 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) in calm seas. When not in use, they were to be retracted into their vertical shafts and protected by water-tight covers.[15]

Flight deck and hangars

editFlight deck

editThe Graf Zeppelins' steel flight deck, overlaid with wooden planking, was 242 m (794 ft) long by 30 m (98 ft) wide at its maximum. It had a slight round down right aft and overhung the main superstructure but not the stern; being supported by steel girders. At the bow, the carriers were to have an open forecastle and the leading edge of her flight deck was uneven (mainly due to the blunt ends of her catapult tracks), but it did not appear likely that would have caused any undue air turbulence. Careful wind-tunnel studies using models confirmed this, but they also revealed that their long low island structure would generate a vortex over the flight deck in these tests when the ship yawed to port. This was considered to be an acceptable hazard when conducting air operations.[16]

Hangars

editThe Graf Zeppelin class's upper and lower hangars were long and narrow with unarmored sides and ends. Workshops, stores and crew quarters were located outboard of the hangars, a design feature similar to that of British carriers.[16] The upper hangar measured 185 m (607 ft) x 16 m (52 ft); the lower hangar 172 m (564 ft) x 16 m (52 ft). The upper hangar had 6 m (20 ft) vertical clearance while the lower hangar had 0.3 m (1 ft 0 in) less headroom due to the ceiling braces. Total usable hangar space was 5,450 m2 (58,700 sq ft) with stowage for 43 aircraft: 20 Fieseler Fi 167 torpedo bombers, 18 in the lower hangar, two in the upper hangar; 13 Junkers Ju 87C dive bombers in the upper hangar and 10 Messerschmitt Bf 109T fighters in the upper hangar.[17]

Elevators

editThe Graf Zeppelin class had three electrically operated elevators positioned along the flight-deck's center-line: one near the bow, abreast the forward end of the island; one amidships; and one aft. They were octagonal in shape, measuring 13 m (43 ft) x 14 m (46 ft), and were designed to transfer aircraft weighing up to 5.5 tons between decks.[18][19]

Launch catapults

editTwo Deutsche Werke compressed air-driven telescoping catapults were installed at the forward end of the flight deck for power-assisted launches. They were 23 m (75 ft) long and designed to accelerate a 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) fighter to a speed of approximately 140 km/h (87 mph) and a 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) bomber to 130 km/h (81 mph).[19]

A dual set of rails led back from the catapults to the forward and midship elevators. In the hangars, aircraft were to be hoisted by crane - a method also proposed for the Essex-class carriers of the United States Navy, but rejected as too time-consuming - onto collapsible launch trolleys. The aircraft/trolley combination would then be lifted to flight deck level on the elevator and trundled along the rails to the catapult start points. When the catapults were triggered, a burst of compressed air would propel moveable slideways within the catapult track wells forward.[20]

As each plane lifted off, its launch trolley would reach the end of the slideway but remain locked in place until the tow attachment cables were released. Once the slideways were retracted back into the catapult track wells and the tow cables unhooked, the launch trollies would be manually pushed forward onto recovery platforms, lowered to the forecastle on "B" deck, then rolled back into the upper hangar for re-use via a secondary set of rails.[20] When not in use, the catapult tracks were to be covered with sheet metal fairings to protect them from harsh weather.[19]

Eighteen aircraft could have theoretically been launched at a rate of one every 30 seconds before exhausting the catapult air reservoirs. It would then have taken 50 minutes to recharge the reservoirs. The two large cylinders holding the compressed air were housed in insulated compartments located between the two catapult tracks, below flight deck level but above the main armored deck. This positioning afforded them only light protection from potential battle damage. The insulated compartments were to be electrically heated to a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) in order to prevent ice from forming on the cylinder piping and control equipment as the compressed air was vented during launches.[21]

It was intended from the outset that all of the Graf Zeppelins' aircraft would normally launch via catapult. Rolling take-offs would be performed only in an emergency or if the catapults were inoperable due to battle damage or mechanical failure. Whether this practice would have been strictly adhered to or later modified, based on actual air trials and combat experience is open to question, especially given the limited capacity of the air reservoirs and the long recharging times necessary between launches.[19] One advantage of such a system, however, was that the Graf Zeppelins could have launched their aircraft without need for turning the ship into the wind or under conditions where the prevailing winds were too light to provide enough lift for her heavier aircraft. They could also have launched and landed aircraft simultaneously.[22]

To facilitate rapid catapult launches and eliminate the necessity of time-consuming engine warm-ups,[Note 1] up to eight aircraft were to be kept in readiness aboard the German carriers on their hangar decks by the use of steam pre-heaters. These would keep the aircraft engines at an operational temperature of 70 °C (158 °F). In addition, engine oil was to be kept warmed in separate holding tanks, then added via hand-pumps to the aircraft engines shortly before launch. Once the aircraft were raised to flight deck level via the elevators, aircraft oil temperature could be maintained, if need be, through the use of electric pre-heaters plugged into power points on the flight deck. Otherwise, the aircraft could have been immediately catapult-launched as their engines would already have been at or near normal operating temperature.[23]

Arresting gear

editFour arrester wires were positioned at the after end of the flight deck with two more emergency wires located afore and abaft of the amidships elevator. Original drawings show four additional wires fore and aft of the forward lift, possibly intended to allow recovery of aircraft over the bows, but these may have been deleted from the ship's final configuration.[18] To assist with night landings, the arrester wires were to be illuminated with neon lights.[22]

Wind barriers

editTwo 4 m (13 ft) high, slitted steel wind barriers were installed afore the midships and forward elevators. These were designed to reduce wind velocity over the flight deck to a distance of approximately 40 m (130 ft) behind them. When not in use they could be lowered flush with the deck to allow aircraft to pass over them.[18]

Island

editThe Graf Zeppelins' starboard-side island housed the command and navigating bridges and charthouse. It also served as a platform for three searchlights, four domed stabilized fire-control directors and a large vertical funnel. To compensate for the weight of the island, the carrier's flight deck and hangars were offset 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) to port from her longitudinal axis.[11] Design additions proposed in 1942 included a tall fighter-director tower, air search radar antennas and a curved cap for her funnel, the latter intended to keep smoke and exhaust gases away from the armored fighter-director cabin.[24]

Armament

editThe Graf Zeppelins were to be armed with separate high and low angle guns for AA and anti-ship defense at a time when most other major navies were switching to dual-purpose AA weapons and relying on escort ships to protect their carriers from surface threats.[15] Her primary anti-shipping armament consisted of sixteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK C/28 guns paired in eight armored casemates. These were mounted, two each, at the four corners of the carriers' upper hangar deck, positions that raised the possibility the guns would be washed out in heavy seas, especially those in the forward casemates.[15]

Chief Engineer Hadeler had originally planned for only eight such weapons on the carriers, four on each side in single mountings. However, the Naval Armaments Office misinterpreted his proposal to save space by pairing them and instead doubled the number of guns to 16, resulting in a need for increased ammunition stowage and more electrically operated hoists to service them.[25] Later in Graf Zeppelin's construction, some consideration was given to deleting these guns and replacing them with 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK C/33 guns mounted on sponsons just below flight deck level. But the structural modifications needed to accommodate such a change were judged too difficult and time-consuming, requiring major changes to the ship's design, and the matter was shelved.[26]

Primary AA protection came from 12 10.5 cm (4.1 in) guns, paired in six turrets positioned three afore and three aft of the carrier's island. Potential blast damage to planes sited on the flight deck when these guns fired to port was an unavoidable risk and would have limited any flight activity during an engagement.[16]

The Graf Zeppelin class's secondary AA defenses consisted of 11 twin 37 mm (1.5 in) SK C/30 guns mounted on sponsons located along the flight deck edges: four on the starboard side, six to port and one mounted on the ship's forecastle. In addition, seven 20 mm (0.79 in) MG C/30 guns were installed on single-mount platforms on either side of the carrier: four to port and three to starboard. These guns were later changed to Flakvierling mountings.[27]

Flight testing at Travemünde

editIn 1937, with Graf Zeppelin's launch scheduled for the end of the following year, the Luftwaffe's experimental test facility at Travemünde (Erprobungsstelle See or E-Stelle See) on the Baltic coast - one of the four such Erprobungstelle facilities of the Third Reich, with the headquarters at Rechlin - began a lengthy program of testing prototype carrier aircraft. This included performing simulated carrier landings and take-offs and training future carrier pilots.[28]

The runway was painted with a contoured outline of Graf Zeppelin's flight deck and simulated deck landings were then conducted over an arresting cable strung width-wise across the airstrip. The cable was attached to an electromechanical braking device manufactured by DEMAG (Deutsche Maschinenfabrik A.G. Duisburg). Testing began in March 1938 using the Heinkel He 50, Arado Ar 195 and Ar 197. Later, a stronger braking winch was supplied by Atlas-Werke of Bremen and this allowed heavier aircraft, such as the Fieseler Fi 167 and Junkers Ju 87, to be tested.[29] After some initial problems, Luftwaffe pilots performed 1,500 successful braked landings out of 1,800 attempted.[30]

Launches were practiced using a 20 m (66 ft) long barge-mounted pneumatic catapult, moored in the Trave River estuary. The Heinkel-designed catapult, built by Deutsche Werke Kiel (DWK), could accelerate aircraft to speeds of 145 km/h (90 mph) depending on wind conditions. Test planes were first hoisted by crane onto collapsible launch carriages in the same manner as intended on Graf Zeppelin.[31]

The catapult test program began in April 1940 and, by early May, 36 launches had been conducted, all carefully documented and filmed for later study: 17 by Arado Ar 197s, 15 by modified Junkers Ju 87Bs and four using a modified Messerschmitt Bf 109D. Further testing followed, and by June Luftwaffe officials were fully satisfied with the catapult system's performance.[32]

Aircraft

editThe expected role of the Graf Zeppelin class was that of a seagoing scouting platform and her initial planned air group reflected that emphasis: 20 Fieseler Fi 167 biplanes for scouting and torpedo attack, 10 Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, and 13 Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers.[5] This was later changed to 30 Bf 109 fighters and 12 Ju 87 dive-bombers as carrier doctrine in Japan, Great Britain and the United States shifted away from purely reconnaissance duties toward offensive combat missions.[5]

In late 1938, the Technische Amt RLM (Technical Office of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium or State Ministry of Aviation) requested that Messerschmitt's Augsburg design bureau draw up plans for a carrier-borne version of the Bf 109E fighter, to be designated Bf 109T (the "T" standing for Träger or Carrier).[33] By December 1940, the RLM decided to complete only seven carrier-equipped Bf 109T-1s and to finish the remainder as land-based T-2s since work on Graf Zeppelin had ceased back in April and there appeared to be little likelihood she would then be commissioned any time soon.[34]

When work on Graf Zeppelin ceased, the T-2s were deployed to Norway. At the end of 1941, when interest in completing Graf Zeppelin revived, the surviving Bf 109 T-2s were withdrawn from front-line service in order to again prepare them for possible carrier duty. Seven T-2s were rebuilt to T-1 standards and handed over to the Kriegsmarine on 19 May 1942. By December, a total of 48 Bf 109T-2s had been converted back into T-1s. 46 of these were stationed at Pillau in East Prussia and reserved for use aboard the carrier. By February 1943, all work on Graf Zeppelin had ceased and the aircraft were returned to Luftwaffe service in April.[35]

When work on Graf Zeppelin was suspended in May 1940, the 12 completed Fi 167s were organized into Erprobungsstaffel 167 for the purpose of conducting further operational trials. By the time work on the carrier resumed two years later in May 1942, the Fi 167 was no longer considered adequate for its intended role and the Technische Amt decided to replace it with a modified torpedo-carrying version of the Junkers Ju 87D.[36] Ten Ju 87C-0 pre-production aircraft were built and sent to the testing facilities at Rechlin and Travemünde where they underwent extensive service trials, including catapult launches and simulated deck landings. Of the 170 Ju 87C-1 ordered, only a few saw completion, suspension of work on Graf Zeppelin in May 1940 resulting in cancellation of the entire order. Existing aircraft and those airframes in process were eventually converted back into Ju 87B-2s.[37]

Work on developing a torpedo-carrying version of the Ju 87D for anti-shipping sorties in the Mediterranean had already commenced in early 1942 when the possibility again arose that Graf Zeppelin might be completed. As the Fieseler Fi 167 was now considered obsolete, the Technische Amt requested that Junkers modify the Ju 87D-4 into a carrier-borne torpedo-bomber/recon plane to be designated Ju 87E-1. But when all further work on Graf Zeppelin was halted for good in February 1943, the entire order was canceled. None of the Ju 87Ds converted to carry a torpedo were used operationally.[38]

By May 1942, when work was ordered resumed on Graf Zeppelin, the older Bf 109T carrier-borne fighter was considered obsolete. By September 1942 detailed plans for the new fighter, the Me 155, were completed. When it became apparent Graf Zeppelin would not be commissioned for at least another two years, Messerschmitt was unofficially told to shelve the projected fighter design. No prototype of the carrier-borne version of the plane was ever constructed.[39]

On 1 August 1938, four months prior to Graf Zeppelin's launch date, the Luftwaffe formed its first carrier-based air unit, designated Trägergruppe I/186, on Rugia Island near Burg. It was composed of three squadrons (Staffeln) and was intended to serve aboard both carriers when completed. By October shipyard construction delays resulted in disbandment of the air group as it was considered too large and costly to maintain given the uncertainty over when the two vessels would be ready for sea trials. Instead, on 1 November that same year a single fighter squadron (Trägerjagdstaffel) was created, 6./186, and placed under the command of Cpt. Heinrich Seeliger.[40]

Later, a dive bomber squadron was added, 4./186, equipped with Ju 87Bs under Cpt. Blattner. Six months after, in July 1939, a second fighter squadron was formed, 5./186, under Oberleutnant Gerhard Kadow and partly staffed with pilots culled from 6./186. By August the three squadrons were reorganised into Trägergruppe II/186 under the command of Major Walter Hagen in anticipation that Graf Zeppelin would be ready for service trials by the summer of 1940.[40]

Ships in class

editConstruction on the Kriegsmarine's two aircraft carriers had been fitful from the start due to a shortage of welders and delays in obtaining materials.

Graf Zeppelin

editWork started on Graf Zeppelin, ordered as Flugzeugträger A, in 1936. She was laid down on 28 December that year, and launched on 8 December 1938. She was incomplete by April 1940, when a changed strategic situation led to work on her being suspended.[41] By early 1942 the usefulness of aircraft carriers in modern naval warfare had been amply demonstrated, and on 13 May 1942, with Hitler's authorization, the German Naval Supreme Command ordered work resumed on the carrier.[42]

With technical problems, such as the demand for newer planes specifically designed for carrier use, and the need for modernization, progress was delayed. The German naval staff hoped all these changes could be accomplished by April 1943, with the carrier's first sea trials taking place that August. By late January 1943 Hitler had become so disenchanted with the Kriegsmarine, especially with what he perceived as the poor performance of its surface fleet, that he ordered all of its larger ships taken out of service and scrapped. As of 2 February 1943, construction on the carrier ended for good.

Graf Zeppelin languished for the next two years in various Baltic ports. On 25 April 1945, she was scuttled at Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland), ahead of the advancing Red Army.[43] The ship was subsequently raised by the Soviets[44] and was used for target practice and sunk in 1947. Her wreck was discovered in 2006 by Polish researchers in the Baltic off Władysławowo, at the head of the Hel Peninsula.[45]

Flugzeugträger B

editThe contract to build the ship was awarded to the Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft in Kiel in 1938, with a planned launch date on 1 July 1940. Work on Flugzeugträger B began in 1938 but was halted on 19 September 1939 because, now that Germany was at war with Great Britain and France, priority had shifted to U-boat construction. The hull, completed only up to the armored deck, sat rusting on its slipway until 28 February 1940, when Admiral Raeder ordered her broken up and scrapped.[46] Scrapping was completed four months later.

The Kriegsmarine never named a vessel before it was launched, so it was only given the designation "B" ("A" was Graf Zeppelin's designation before launch). Had it been completed, the aircraft carrier could have been named Peter Strasser in honor of the World War I leader of the naval airships Peter Strasser.[47]

Flugzeugträger C and D

editIn 1937, the Kriegsmarine planned two additional aircraft carriers of the Graf Zeppelin class with the official designations C and D. Both these carriers were planned to be operational by 1943. However, by the end of 1938, this plan was changed to only build these two carriers plus any further units as smaller carriers.[48]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ As almost all the existing aircraft types being considered for carrier use by the Third Reich were powered by various Daimler-Benz or Junkers-designed inverted V12 liquid-cooled engines, unlike either the U.S. Navy or IJNAF, who both generally preferred air-cooled radial engines for their carrier aircraft.

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 226

- ^ Reynolds, p. 42

- ^ Reynolds, p. 43

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, pp. 226–227

- ^ a b c Reynolds, p. 44

- ^ a b Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 227

- ^ Gröner, p. 71

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 220

- ^ Gröner, pp. 71–72

- ^ Gröner, p. 72

- ^ a b c Breyer, p. 33

- ^ a b c Whitley (1985), p. 157

- ^ Brown, p. 9

- ^ Whitley (1984), p. 31

- ^ a b c d Whitley (1985), p. 159

- ^ a b c Brown, p. 10

- ^ Breyer, p. 52

- ^ a b c Whitley (1985), p. 155

- ^ a b c d Breyer, p. 54

- ^ a b Wagner & Wilske, pp. 54–56

- ^ Burke, p. 87

- ^ a b Marshall, p. 23

- ^ Burke, p. 86

- ^ Breyer, p. 18

- ^ Breyer, p. 43

- ^ Breyer, p. 44

- ^ Breyer, p. 48

- ^ Reynolds, p. 46

- ^ Israel, p. 66

- ^ Breyer, p. 66

- ^ Breyer, p. 67

- ^ Israel, p. 65

- ^ Marshall, p. 16

- ^ Marshall, p. 24

- ^ Breyer, p. 69

- ^ Green, p. 169

- ^ Breyer, p. 72

- ^ Breyer, p. 73

- ^ Green, p. 88

- ^ a b Breyer, p. 55

- ^ Whitley (1984), p. 30

- ^ Reynolds, p. 47

- ^ Breyer, p. 32

- ^ Chesneau, pp. 76-77, 190

- ^ "Geschichte - DER SPIEGEL".

- ^ Breyer, p. 14

- ^ Ireland, p. 176

- ^ Carl Dreessen: "Die deutsche Flottenrüstung." Mittler & Sohn. Hamburg 2000. p. 101

References

edit- Breyer, Siegfried (1989). The German Aircraft Carrier Graf Zeppelin. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

- Breyer, Siegfried (2004). Encyclopedia of Warships 42: Graf Zeppelin. Gdansk: A.J. Press.

- Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. New York: Arco Publishing.

- Burke, Stephen (2007). Without Wings: The Story of Hitler's Aircraft Carrier. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-2216-4.

- Chesneau, Roger (1998). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present. An Illustrated Encyclopedia (Rev Ed). London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-87-5-9.

- Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-913-8.

- Green, William (1979). The Warplanes of the Third Reich. New York: Doubleday and Company.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Ireland, Bernard (1998). Jane's Naval History of World War II. New York: Collins Reference.

- Israel, Ulrich H.-J. (2003). ""Flugdeck klar!" Deutsche Trägerflugzeuge bis 1945". Flieger Revue Extra.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Marshall, Francis L. (1994). Sea Eagles - The Operational History of the Messerschmitt Bf 109T. Walton on Thames: Air Research Publications.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (January 1967). "Hitler's Flattop: The End of the Beginning". United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Schenk, Peter (2008). "German Aircraft Carrier Developments". Warship International. 45 (2). Toledo: International Naval Research Organization: 129–158. ISSN 0043-0374. OCLC 1647131.

- Wagner, Richard & Manfred Wilske (2007). Flugzeugträger Graf Zeppelin: Das Original, Das Modell, Die Flugzeuge. Neckar-Verlag.

- Whitley, M.J. (July 1984). "Warship 31: Graf Zeppelin, Part 1". London: Conway Maritime Press Ltd.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Whitley, M.J. (1985). Warship 33, Vol IX: Graf Zeppelin, Part 2. London: Conway Maritime Press Ltd.

Further reading

edit- Burke, Stephen & Adam Olejnik (2010). Freedom of the Seas: The Story of Hitler's Aircraft Carrier - Graf Zeppelin. Stephen Burke Books. ISBN 978-0-9564790-0-6.

- Faulkner, Marcus (2012). "The Kriegsmarine and the Aircraft Carrier: The Design and Operational Purpose of the Graf Zeppelin". War in History. 19 (4). SagePub: 492–516. doi:10.1177/0968344512455974. S2CID 108704626.

- Israel, Ulrich H.-J. (1994). Graf Zeppelin: Einziger Deutscher Flugzeugträger. Hamburg: Verlag Koehler/Mittler.

- Mueller, William B. (March 2018). "Hitler's Carrier". Sea Classics, Vol. 51, no.3.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

edit- "Graf Zeppelin Rediscovered – Hitler's Showpiece Aircraft Carrier Found." Spiegel Online International article dated 27-7-2006. Retrieved 20-9-2010.

- A video with photos of the unfinished Graf Zeppelin