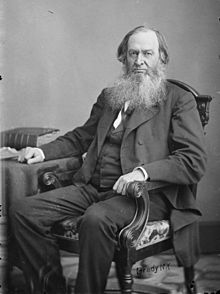

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was an American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidate for President of the United States in 1848, 1856, and 1860. He served a single term in the House of Representatives from 1853 to 1854.[1]

Gerrit Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 22nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – August 7, 1854 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Bennett |

| Succeeded by | Henry C. Goodwin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 6, 1797 Utica, New York, U.S. |

| Died | December 28, 1874 (aged 77) New York City, U.S. |

| Political party | Liberty (1840s) Free Soil (1850s) |

| Spouse(s) | Wealtha Ann Backus (Jan. 1819 – Aug. 1819; her death) |

| Children | Elizabeth Smith Miller and Greene Smith |

| Occupation | social reformer, abolitionist, politician, businessman, public intellectual, philanthropist |

First valedictorian of the new Hamilton College (1818), and married to the daughter of the college president, he had "a fine mind", with "a strong literary bent and a marked gift for public speaking".[2]: 25 He was called "the sage of Peterboro."[3]: ix He was well liked, even by his political enemies. The many who appeared at his house in Peterboro, invited or not, were well received. (In 1842 the names of 132 visitors were recorded.[4]: 28 )

Smith, one of the wealthiest men in New York, was committed to political reform, and above all to the elimination of slavery. So many fugitive slaves came to Peterboro to ask for his help (usually, in reaching Canada) that there is a book about them.[5] Peterboro was, because of Smith, the capital of the abolition movement. The only assembly of escaped slaves (as opposed to free Blacks) ever to meet in the United States—the Fugitive Slave Convention of 1850—took place in neighboring Cazenovia because Peterboro was too small for the meeting.

Smith was also, and less successfully, a temperance activist, and a women's rights suffrage advocate. He was a significant financial contributor to the Liberty Party and the Republican Party throughout his life. Besides making substantial donations of both land and money to create Timbuctoo, an African-American community in North Elba, New York, he was involved in the temperance movement and the colonization movement,[6] before abandoning colonization in favor of abolitionism, the immediate freeing of all the slaves. He was a member of the Secret Six who financially supported John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry, in 1859.[7]: 13–14 Brown's farm, in North Elba, was on land he bought from Smith.

Early life

editForebears

editSmith was born in Utica, New York, when it was still an unincorporated village.[3]: ix He was one of four children of Peter Gerrit Smith (1768–1837), whose ancestors were from Holland (Gerrit is a Dutch name),[8]: 27 and Elizabeth (Livingston) Smith (†1818), daughter of Col. James Livingston and Elizabeth (Simpson) Livingston. Peter, an actor as a young man, and who coached Gerrit in public speaking,[9]: 44 was a slave owner,[10]: 154 the first judge in Madison County,[11] and the largest landholder in New York State.[12] "In partnership with John Jacob Astor in the fur trade and alone in real estate, Peter Smith [had] managed to amass a considerable fortune. Peter was the county judge of Madison County, New York, and has been described as 'easily its leading citizen'."[8]: 27 He was "a devout and emotionally religious man".[citation needed] From 1822 on, Peter Smith was intensely engaged in the work of the Bible and tract societies."[8]: 28

The author of the only book on Peter calls him greedy, self-centered, driven by the search for profits, and someone who did not like people who were not like him: white, male, and Dutch.[10]: 153–154 He was not philanthropic.[9]: 39 "Other people...[were] objects to be used for his own benefit, especially if they were culturally different than himself. Native Americans, poor people, black people, and non-Christians he viewed with disrepect."[9]: 11

Peter spent his last years in a religious fanaticism that led him to give up all his worldly goods.[7]: 16 He turned over a $400,000 business [equivalent to $7,961,739 in 2023] to his son Gerrit in 1819 and bequeathed $800,000 more [equivalent to $16,955,556 in 2023] to his children in 1837. Gerrit also inherited 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of land from his father, and at one point he owned 750,000 acres (300,000 ha), an area bigger than Rhode Island.[13] Another source says that he inherited from his father over one million acres in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York.[14] An 1846 listing of lands he was offering for sale fills 45 pages.[15]

Gerrit had an older brother, Peter Smith Jr., who was a problem drinker that died young, and a younger brother Adolph, who was "clinically insane and confined to a nearby institution."[7]: 15

Smith's maternal aunt, Margaret Livingston, was married to Judge Daniel Cady. Their daughter Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a founder and leader of the women's suffrage movement, was Smith's first cousin. Elizabeth Cady met her future husband, Henry Stanton, also an active abolitionist, at the Smith family home in Peterboro, New York.[16] Established in 1795, the town had been founded by and named for Gerrit Smith's father, Peter Smith, who built the family homestead there in 1804.[7]: 16 [17] Another source says that Peter Smith moved to Whitesboro "about 1803" and that he removed to Peterboro in 1806.[18] Gerrit came there when he was 9.[8]: 27

Gerrit as a young man

editGerrit was described as "tall, magnificently built and magnificently proportioned, his large head superbly set on his shoulders;" he "might have served as a model for a Greek god in the days when man deified beauty and worshipped it."[19]: 42 He attended Hamilton Oneida Academy in Clinton, Oneida County, New York, and graduated with honors from its successor Hamilton College in 1818, giving the valedictory address, and describing his stay at the college as "very active with many friends".[8]: 28 (His father was one of the trustees.[20]) In January 1819, he married Wealtha Ann Backus (1800–1819), daughter of Hamilton College's first President, Azel Backus D.D. (1765–1817), and sister of Frederick F. Backus (1794–1858). Wealtha died in August of the same year. In 1822, he married 16-year-old Ann Carroll Fitzhugh (1805–1879), sister of Henry Fitzhugh (1801–1866) and of Wealtha's brother's wife.[4]: 7 Their relationship "appeared to be loving";[citation needed] although Ann was a religious, church-going person who worried that Gerrit was not.[4]: 9 They had eight children, but only Elizabeth Smith Miller (1822–1911), mother of his grandson Gerrit Smith Miller, and Greene Smith (c. 1841–1880) survived to adulthood.[11][21]

In the year of his graduation, the death of his mother plunged his father, Peter, into severe depression. He withdrew from all business and vested in his second son Gerrit, who had to abandon plans for a law career, the entire charge of his estate,[2]: 25 described as "monumental".[8]: 28

He became an active temperance campaigner, and attended temperance gatherings more than political ones.[9]: 153 He claimed to have given in 1824 the first temperance speech ever in the New York State Legislature.[22] In his hometown of Peterboro, he built one of the first temperance hotels in the country, which was not successful commercially, and was disliked by many locals.

Smith wrote of himself:

But as an extemporaneous Speaker and Debater, we do not hesitate to place him in the first class. Here his eloquence is the growth of the hour and the occasion. He warms with the subject, especially if opposed, until at the climax, his heavy voice rolling forth in ponderous volume and his large frame quivering in every muscle, he stands, like Jupiter, thundering, and shaking with his thunderbolts his throne itself.[22]

Gerrit in the 1830s

editHe attended numerous revival meetings, and taught Sunday school. He thought of establishing a seminary for Black students. In 1834 he began a Peterboro manual labor school for Black students,[8]: 30 along the model of nearby Oneida Institute. It had only one instructor, and it lasted only two years.[23][19]: 42 Previously a supporter of the American Colonization Society, he became an abolitionist in 1835 after a mob in Utica, including New York congressman and future Attorney General Samuel Beardsley, broke up the initial meeting of the New York Anti-Slavery Society, which he attended at the urging of his friends Beriah Green and Alvan Stewart.[8]: 32 [19]: 43 At his invitation, the meeting continued the next day in Peterboro.[24] He resigned as a trustee of Hamilton College "on the grounds that the school was insufficiently anti-slavery", and joined the board of and financially assisted the Oneida Institute, "a hotbed of anti-slavery activity".[19]: 44 He contributed $9,000 (equivalent to $265,819 in 2023) to support schools in Liberia, but realized by 1835 that the American Colonization Society had no intention of abolishing slavery.[8]: 31

Smith was a laggard instead of a leader in changing from supporting colonization to "immediatism", immediate full abolitionism. Support for Jefferson Davis after the war would have been unthinkable for Garrison, Douglass, or other abolitionist leaders.

Gerrit's stately house was not only an Underground Railroad stop, it received a constant stream of visitors. (See Peterboro, New York#Gerrit Smith.) His desk was said to have belonged to Napoleon. Besides a library of 1,000 volumes, on the wall was a framed map of the Eastern Seaboard, with his extensive land-holdings marked.[25]: 15

Political career

edit"It must be admitted that few men in this country have been a candidate for high office so many times and polled so few votes."[2]: 29

In 1840, Smith played a leading part in the organization of the Liberty Party; the name of the party was his.[3]: xi In the same year, their presidential candidate James G. Birney married Elizabeth Potts Fitzhugh, Smith's sister-in-law. Smith and Birney travelled to London that year to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London.[26]

Birney, but not Smith, is recorded in the commemorative painting of the event. In 1848, Smith was nominated for the Presidency by the remnant of this organization that had not been absorbed by the Free Soil Party. An "Industrial Congress" at Philadelphia also nominated him for the presidency in 1848, and the "Land Reformers" in 1856. In 1840 and again in 1858, he ran for Governor of New York on an anti-slavery platform.[27]

On June 2, 1848, in Rochester, New York, Smith was nominated as the Liberty Party's presidential candidate.[28] At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in Buffalo, New York, Smith gave a major address,[29] including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote."[28] The delegates approved a passage in their address to the people of the United States addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes. This universal exclusion of woman...argues, conclusively, that, not as yet, is there one nation so far emerged from barbarism, and so far practically Christian, as to permit woman to rise up to the one level of the human family."[28] Reverend Charles C. Foote was nominated as his running mate. The ticket would come in fourth place in the election, carrying 2,545 popular votes, all from New York.[30]

At the request of friends, Smith had 3,000 copies printed of an 1851 speech in Troy in which he set forth his views of government.[31] Smith laments the people's universal dependence on government. As a consequence of that dependence, government occupies itself "for the most part, in doing that it belongs to the people to do". He opposed tariffs, internal improvements, such as the Erie Canal, at public expense, and publicly-supported schools, which could not teach religion, which Smith thought the main function of schools. The remedy was less government, and the less, the better.[32]

The only political office to which Smith was ever elected, and that by a very large majority,[33]: 9 was Representative in the U.S. Congress. Smith served a single term in Congress, on the Free Soil ticket, from March 4, 1853, until the end of the session on August 7, 1854, although he said that because of his business activities he had sought neither the nomination nor his election.[33] ("My nomination to Congress alarmed me greatly, because I believed that it would result in my election."[34]) He made a point of resigning his seat on the last day of the session. He then published a lengthy letter to his constituents explaining his frustrations in Congress and his decision not to run for a second term.[35][34] He was well liked, even by Southern members, who found him "one of the best fellows in the Capitol, as one, although well known as an abolitionist, still as one to be tolerated".[36]

By 1856, very little of the Liberty Party remained after most of its members joined the Free Soil Party in 1848 and nearly of all what remained of the party joined the Republicans in 1854. The small remnant of the party renominated Smith under the name of the "National Liberty Party".

In 1860, the remnant of the party was also called the Radical Abolitionists.[37][38] A convention of one hundred delegates was held in Convention Hall, Syracuse, New York, on August 29, 1860. Delegates were in attendance from New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, and Massachusetts. Several of the delegates were women. Smith, despite his poor health, fought William Goodell in regard to the nomination for the presidency. In the end, Smith was nominated for president and Samuel McFarland from Pennsylvania was nominated for vice president. The ticket won 171 popular votes from Illinois and Ohio. In Ohio, a slate of presidential electors pledged to Smith ran with the name of the Union Party.[39]

Smith, along with his friend and ally Lysander Spooner, was a leading advocate of the United States Constitution as an antislavery document, as opposed to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who believed it was to be condemned as a pro-slavery document, and was in favor of secession by the North. In 1852, Smith was elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Free-Soiler. In his address, he declared that all men have an equal right to the soil; that wars are brutal and unnecessary; that slavery could be sanctioned by no constitution, state or federal; that free trade is essential to human brotherhood; that women should have full political rights; that the Federal government and the states should prohibit the liquor traffic within their respective jurisdictions; and that government officers, so far as practicable, should be elected by direct vote of the people.[27] Unhappy with his separation from his home and business, Smith resigned his seat at the end of the first session, ostensibly to allow voters sufficient time to select his successor.[40]

In 1869, Smith served as a delegate to the founding convention of the Prohibition Party.[41] During the 1872 presidential election Smith was considered for the Prohibition Party's presidential nomination.[42]

Support for Black people

editAccording to Black Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, who moved there at Smith's invitation,[43] "There are yet two places where slave holders cannot come—Heaven and Peterboro."[44]

The failed land redistribution project (Timbuctoo)

editAfter becoming an opponent of land monopoly, he gave numerous farms of 50 acres (20 ha) each to 1,000 "worthy" New York state Blacks.[45] In 1846, hoping to help black families become self-sufficient, to isolate and thus protect them from escaped slave-hunters, and to provide them with the property ownership that was needed for Blacks to vote in New York, Smith attempted to help free blacks settle approximately 120,000 acres (49,000 ha) of land he owned in the remote Adirondacks. Abolitionist John Brown joined his project, purchasing land and moving his family there. However, the land Smith gave away was "of but moderate fertility", "heavily timbered, and in no respect remarkably inviting".[45] In Smith's own words, it was his "poorest land"; his better land he sold.[46]

Most grantees never saw the remote land Smith had given them; many of those who did visit it soon left, and in 1857, it was estimated that less than 10% of the grantees were actually living on their land.[46] The difficulty of farming in the mountains, coupled with the settlers' lack of experience in housebuilding and farming and the bigotry of white neighbors, caused the project to fail.[7]: 17–18 As Smith put it, "I was perhaps a better land-reformer in theory than in practice."[46] The John Brown Farm State Historic Site is all that remains of the settlement, called Timbuctoo, New York.

The Chaplin slave escape

editPeterboro became a station on the Underground Railroad.[27] Due to his connections with it, Smith financially supported a planned mass slave escape in Washington, D.C., in April 1848, organized by William L. Chaplin, another abolitionist, as well as numerous members of the city's large free black community. The Pearl incident attracted widespread national attention after the 77 slaves were intercepted and captured about two days after they sailed from the capital.[47]

The Fugitive Slave Convention

editThe Fugitive Slave Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. It was a fugitive slave meeting, the biggest ever held in the United States. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring Peterboro, New York, and called the meeting "in behalf of the New York State Vigilance Committee."

Defending Fugitive Slave Law violators

editSmith paid the legal expenses of several persons charged with infractions of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.[7]: 12

Helping John Brown in Kansas

editSmith became a leading figure in the Kansas Aid Movement, a campaign to raise money and show solidarity with anti-slavery immigrants to that territory.[48]: 351 It was during this movement that he first met and financially supported John Brown.[49][full citation needed][48][page needed]

Harpers Ferry

editSmith was a member of what much later was called the Secret Six, a informal group of influential Northern abolitionists, who supported Brown in his efforts to capture the armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia), and start a slave revolt. After the failed raid on Harpers Ferry, Senator Jefferson Davis unsuccessfully attempted to have Smith accused, tried, and hanged along with Brown.[7]: 12 Governor Wise suggested that Smith be brought to him, "by fair or foul means",[50] but residents of Peterboro said publicly that they would use guns to protect him.[51]

Upset by the raid, its outcome, and its aftermath, expecting to be indicted, Smith suffered a mental breakdown; he was described in the press as "a raving lunatic", who became "very violent".[52] For several weeks he was confined to the Utica Psychiatric Center, at the time called the State Lunatic Asylum.[7]: 13–14 [53] He was accused of feigning his illness, but multiple reports state that it was genuine.[53][54]: 49–54 He was initially on a suicide watch.[52][55]

When the Chicago Tribune later claimed Smith had full knowledge of Brown's plan at Harper's Ferry, Smith sued the paper for libel, claiming that he lacked any such knowledge and thought only that Brown wanted guns so that slaves who ran away to join him might defend themselves against attackers.[56] Smith's claim was countered by the Tribune, which produced an affidavit, signed by Brown's son, swearing that Smith had full knowledge of all the particulars of the plan, including the plan to instigate a slave uprising. In writing later of these events, Smith said, "That affair excited and shocked me, and a few weeks after I was taken to a lunatic asylum. From that day to this I have had but a hazy view of dear John Brown's great work. Indeed, some of my impressions of it have, as others have told me, been quite erroneous and even wild."[7]: 13–14 Ralph Harlow concluded his examination of the episode with this quote from Brown: "G S he knew to be a timid man".[54]: 60

While in the New York Lunatic Asylum, now the Utica Psychiatric Center, he was treated with cannabis and morphine.[57]: 512

Other social activism

editSmith was a major benefactor of New-York Central College, a co-educational and racially integrated college in Cortland County.[58]

Smith supported the American Civil War, but at its close he advocated a mild policy toward the late Confederate states, declaring that part of the guilt of slavery lay upon the North.[59] In 1867, Smith, together with Horace Greeley and Cornelius Vanderbilt, helped to underwrite the $100,000 (~$1.79 million in 2023) bond needed to free Jefferson Davis, who had, at that time, been imprisoned for nearly two years without being charged with any crime.[7]: 11 In doing this, Smith incurred the resentment of Northern Radical Republican leaders.

Smith's passions extended to religion as well as politics. Believing that sectarianism was sinful, he separated from the Presbyterian Church in 1843. He was one of the founders of the Church at Peterboro, a non-denominational institution open to all non-slave-owning Christians.[59]

His private benefactions were substantial; of his gifts he kept no record,[citation needed] but their value is said to have exceeded $8,000,000. Though a man of great wealth, his life was one of marked simplicity.[59] He died in 1874 while visiting relatives in New York City.

The Gerrit Smith Estate, in Peterboro, New York, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2001.[60][61]

Tribute

editFrederick Douglass dedicated to Smith My Bondage and My Freedom (1855):

To honorable Gerrit Smith, as a slight token of esteem for his character, admiration for his genius and benevolence, affection for his person, and gratitude for his friendship, and as a small but most sincere acknowledgement of his pre-eminent services in [sic] behalf of the rights and liberties of an afflicted, despised and deeply outraged people, by ranking slavery with piracy and murder, and by denying it either a legal or Constitutional existence, this volume is respectively dedicated, by his faithful and firmly attached friend, Frederick Douglass.

Years before, a student at his Peterboro Manual Labor School, where "Mr. Smith liberally supplies us with stationery, books, board and lodging", stated that "if the man of color has a sincere friend, that friend is Gerrit Smith".[62]

A visitor to Smith's house in 1870 described it as follows:

I have visited many houses...but never before one like this. One breathing the affluence of wealth without a touch of its insolence, characterized by refinement and the highest culture, yet free from all the impertinance of display. Plainness of attire, simplicity of manner, absolute sincerity, and an all-pervading spirit of love characterize the family and give tone to the home—a home free from press and hurry and confusion, where differences of opinion are expressed without irritation, where the individual is respected, where the younger members of the family are reverent and the older ones considerate, where all are mindful of the interests of each, and each is thoughtful for all.[9]: 35

Philanthropic activities

editMoney was for Smith a resource that belonged to others, a divine gift to be used for the common good.[9]: 43 Smith provided support for a large number of progressive causes and people and, except for his land grants, did not keep careful records. The dates given are in some cases approximate, either because documents do not provide a definite date, or because there were multiple payments.

- "200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of his land he had divided among various destitute people, and 650 poor women have received money from him to help provide themselves with homes."[22]

- Built and ran unsuccessful temperance hotel on his property in Peterboro, 1827–1833.[63] It reopened in 1845 but was no more successful. He also established an unsuccessful temperance hotel in Oswego.[citation needed]

- Supporter of American Colonization Society, 1820s–early 1830s.

- Support for the Oneida Institute, the first school at which both Blacks and whites were welcomed, 1830s.

- Manual labor school for "colored boys" in Peterboro, 1834–1836 (two years). Benjamin Quarles suggests that Smith may have ended the project because it was duplicating what was available at the nearby Oneida Institute, headed by his friend Beriah Green.[64] Another scholar suggests that the school closed because of Smith's disillusionment with the American Colonization Society, as the school had set upon preparing students to Christianize Africa.[9]: 147–148

- Created in Peterboro a group home to support economically destitute children.[9]: 30

- Founder of nondenominational Free Church of Peterboro, 1843.[9]: 41 (Dissatisfied with existing churches' refusal to insist on abolition.)

- Supported Frederick Douglass' abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, late 1840s. Douglas dedicated the second of his autobiographies to Gerrit.[7]: 16

- Supported planned mass slave escape in Washington, DC, in April 1848, organized by William L. Chaplin.

- Provided land in North Elba, New York, to support Timbuctoo settlement of Black farmers, 1848.

- Sold land in North Elba to John Brown "for a bargain price of $1 an acre".[53]

- Major benefactor of New-York Central College, 1850s.

- Helped with legal expenses of Fugitive Slave Law violators, 1850s. Primary sponsor of the Fugitive Slave Convention, held in neighboring Cazenovia.

- In 1851, he funded the establishment of an educational academy in Peterboro.[9]: 149

- About 1855, gave $25,000 (equivalent to $817,500 in 2023) to build the Oswego City Library, and $5,000 for books.

- Leading figure in the New England Emigrant Aid Society (Kansas Aid Movement), assisting abolitionist settlers and John Brown working to make Kansas a free state, 1850s.

- Between 1856 and 1874, donated money to "interracial colleges": Berea College, Hampton Agricultural Institute, Dartmouth College, and Howard University.[9]: 149

- Paid for printing of James Redpath's The Roving Editor: or, Talks with Slaves in the Southern States, 1859.

- One of Secret Six that helped finance John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry, 1859

- With Horace Greeley and Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of guarantors of Jefferson Davis's bond, 1867.[25]: 11

- Supported William G. Allen and family financially during their poverty in London, 1870s and 1880s.

After his death, a newspaper reported his philanthropic activities as follows:

His private benefactions were boundless. He literally gave away fortunes to relieve immediate distress. Old men and women asked for sustenance in their infirmity. To redeem farms, to buy unproductive land, to send children to school, applications were made from every part of the country.

But permanent institutions, too, bear witness to the solid character of his bounty. The public subscription papers of his times usually bore his name at the head and for the largest sum. There were $5,000 to a single war fund. The English destitute received at one time $1,000, the Poles $1,000, the Greeks as much more. The sufferers by a fire at Canastota received the next morning $1,000. The sufferers by the Irish famine were gladdened by a gift of $2,000. A thousand went to the sufferers from the grasshoppers in Kansas and Nebraska. The Cuban subscriptions took $5,000. Individuals in distress, anti-slavery men, temperance reformers, teachers, hard-working ministers of whatever denomination, received sums all the way from $500 to $50. In cases when money was required to vindicate a principle—as in the Chaplin case—thousands of dollars were contributed, To keep slavery out of Kansas cost him $18,000. He helped on election expenses, maintained papers, supported editors and their families, was at perpetual charge for the maintenance of societies organised for particular reforms. The free library at Oswego, an admirable institution, comprising about six thousand wisely selected volumes, with less trash than any public collection of books we ever saw, owes its existence to his endowment of $30,000 (~$867,163 in 2023) in 1853. Judicious management, seconded by the liberality of the city, makes this library minister to the higher intellectual culture. His own college, Hamilton, received $20,000; Oneida Institute thousands at a time; Oberlin, a pet with him on account of its freedom from race and sex prejudice, was endowed with land as well as aided by money. The New York Central College appealed to him, not in vain. The Normal School at Hampton obtained in response to an appeal in 1874 $2,000 (~$48,616 in 2023). Reading rooms, libraries, academies of all degrees drew resources from him. Seminaries in Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Vermont, tasted his bounty. General R. E. Lee's Washington College was as welcome as any to what he had to bestow. Berea College in Kentucky, received in 1874 $4,720 (~$114,734 in 2023). Storer College, at Harper's Ferry, received the same year two donations each of a thousand dollars. Fisk University, at Nashville, the Howard University at Washington, drew handsomely from his stores. He at one period, shortly before the establishment of Cornell University, projected a great university for the State of New York, for the highest education of men and women, white and black, and would have carried his plan into execution but for the difficulty of procuring the superintendent he wanted. His donation of $10,000 to the Colonization Society because he had pledged it, though when he paid the money he had satisfied himself that the society was not what he had been led to believe—was considered by many abolitionists a proceeding the chivalrous honor whereof hardly excused the indiscreet support given to what he now regarded as a fraud. His charges for the rescue and maintenance of fugitive[s] from southern slavery were very heavy; in one year they amounted to $5,000. To meet the incessant casual calls that were made on him, it was a custom to have checks prepared and only requiring to be signed and filled in with the applicant's name, for various amounts. No call of peculiar necessity escaped his attention, and his bounty was as delicate as it was generous. Whole households looked to him as their preserver and constant benefactor. A unique example of his benevolence was his donation, through committees, of a generous sum of money, as much as $30,000, to destitute old maids and widows in every county of the State. The individual gift was not great, $50 to each, but the total was considerable; the humanity expressed in the idea is chiefly worth considering.[65]

Honors

editIn 2005 Smith was inducted into the National Abolition Hall of Fame, in Peterboro, New York.

Writings

editSmith paid for the printing of hundreds of broadsides, with his views on a variety of subjects. His own collection of his pamphlets is in the Syracuse University Library. A number of recipients bound those they received into volumes, different contents for each collector.

- Smith, Gerrit (1922) [March 23, 1829]. "Letter to Andrew Yates". Documentary History of Hamilton College. Clinton, New York: Hamilton College. pp. 201–208.

- Smith, Gerrit (1833). Letter from Gerit [sic] Smith, to Edward C. Delavan, esq. on the reformation of the intemperate. Albany, New York. OCLC 79910882.

- Smith, Gerrit (1835). "Speech of Mr. Gerrit Smith". Proceedings of the New York Anti-Slavery Convention : held at Utica, October 21, and New York Anti-Slavery State Society : held at Peterboro, October 22, 1835. pp. 18–23.

- Smith, Gerrit (1837). Letter of Gerrit Smith to Hon. Gulian C. Veplanck. [Calling on the New York Legislature to remove legal discrimination towards "our colored inhabitants".] Whitesboro, New York.

- Smith, Gerrit (1837). Letter of Gerrit Smith to Rev. James Smylie, of the state of Mississippi. New York: R.G. Williams, for the American Anti-Slavery Society.

- Liberty Party (N.Y.). State Convention (1842). Address of the Peterboro State Convention to the slaves, and its vindication. Cazenovia, New York. Probably written by Smith. Includes (pp. 16–23) an "Extract from a letter by Gerrit Smith to Rev. Wm. H. Brisbane".

- Smith, Gerrit (1844). Constitutional Argument against American Slavery. [In the form of a letter to John G. Whittier.] Utica, New York: Jackson & Chaplin.

- Smith, Gerrit (1846). Gerrit Smith's land auction. For sale, and the far greater share at public auction, about three quarters of a million of acres of land, lying in the State of New-York.

- Smith, Gerrit (1846). An address to the three thousand colored citizens of New-York : who are the owners of one hundred and twenty thousand acres of land, in the state of New-York, given to them by Gerrit Smith, Esq. of Peterboro, September 1, 1846. New York.

- Smith, Gerrit (1847). Abstract of the argument, in the public discussion of the question: "Are the Christians of a given community the church of such community?" made by Gerrit Smith, in Hamilton College, April 12th, 13th, 14th, 1847. Albany, New York.

- Smith, Gerrit (October 16, 1850) [October 7, 1850]. "Gerrit Smith's appeal, and the Fugitive Slave Law". Madison County Whig. Cazenovia, New York. p. 7 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- Smith, Gerrit (1851). The True Office of Civil Government. A Speech in the City of Troy. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (1852). Abstract of the argument on the fugitive slave law, made by Gerrit Smith, in Syracuse, June, 1852, on the trial of Henry W. Allen, U.S. deputy marshal, for kidnapping. Syracuse, New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (1853) [December 20, 1853]. Speech of Gerrit Smith, in Congress, on the reference of the President's message. [Smith's first speech on the floor of Congress. On the Koszta Affair.] Washington, D.C.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (1855). Speeches of Gerrit Smith in Congress [1853–1854]. New York: Mason Brothers.

- Smith, Gerrit; New York Tribune (1855). Controversy between New-York Tribune and Gerrit Smith. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (July–August 1858). "Peace better than war : annual address delivered before the American Peace Society, in Boston, May 24th, 1858". The Advocate of Peace: 97–118.

- Smith, Gerrit (1859). Three discourses on the religion of reason. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (1860). Gerrit Smith and the Vigilant Association of the City of New-York. [On slavery.] New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (1864). Speeches and letters of Gerrit Smith (from January, 1863, to January, 1864) on the rebellion. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Gerrit (1865). Sermon in Peterboro, May 21, 1865. The nation still unsaved, Only repentance can save it. Author not stated, but Library of Congress catalogued it as a work of Smith. There was no one else in Peterboro that could have written it. Peterboro? N.Y.

- Smith, Gerrit (1873). "Rescue Cuba Now" : Let crushed Cuba arise. Substance of the speech delivered in Syracuse, July 4, 1873. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Archival material

editSmith's grandson, Gerrit Smith Miller, was the final resident of the Smith mansion. In 1928, before it burned, he donated Smith's enormous collection of letters, documents, diaries, and daybooks to the Syracuse University Library, along with a pamphlet and broadside collection of over 700 items.[66] There is nothing like it for any other businessman of his day.

- Gerrit Smith Papers, Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center. 10,000 letters,[67] 74 boxes. Library description of holdings: "Business, family and general correspondence; business and land records; writings; and maps. Notable correspondents include Susan B. Anthony, John Jacob Astor, Henry Ward Beecher, Antoinette Blackwell, Caleb Calkins, Lydia Maria Child, Cassius Clay, Alfred Conkling, Roscoe Conkling, Charles A. Dana, Paulina W. Davis, Edward C. Delavan, Frederick Douglass, Albert G. Finney, Sarah Grimké, Elizabeth Cady and Henry B. Stanton, Louis Tappan, Sojourner Truth, and Theodore Weld." The collection has been microfilmed, and together with materials of his father Peter Smith, fills 89 reels.[68][69] A partial calendar of the general correspondence was published in 1941.[70] The Special Collections Research Center of Syracuse University also holds Smith's pamphlet collection, "700+ items", which has also been microfilmed, and over half digitized and available online.[71][66]

- Another important collection of documents related to Gerrit Smith is found in the archives of his alma mater, Hamilton College, in Clinton, Oneida County, New York.[72]

- Additional documents are in the collections of the Peterboro and the Madison County Historical Societies.[72]

See also

edit- Gerrit Smith Estate

- Peterboro Land Office

- Peterboro, New York

- List of recipients of aid from Gerrit Smith

- National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum

- Peterboro Area Museum

- Fugitive Slave Convention (Cazenovia, New York)

Relatives of Smith

edit- Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, wife

- Elizabeth Smith Miller, daughter

- Greene Smith, son

- Gerrit Smith Miller, grandson

- Gerrit Smith Miller Jr., great-grandson

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, cousin

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Back to Africa: Benjamin Coates and the colonization movement in America. Penn State Press. 2005. p. 88. ISBN 0-271-02684-7. Archived from the original on 2014-01-11. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ^ a b c Tanner, E. P. (January 1924). "Gerrit Smith: An Interpretation". Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association. 5 (1): 21–39. JSTOR 43554023. Archived from the original on 2022-04-14. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ^ a b c Historical Records Survey. Division of Community Service Programs. Work Projects Administration (1941). "Introduction". Calendar of the Gerrit Smith Papers in the Syracuse University Library. Introduction by George W. Roach. Albany, New York. Archived from the original on 2022-08-18. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Dann, Norman K. (2016). Ballots, Bloomers and Marmalade. The Life of Elizabeth Smith Miller. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. ISBN 9780997325102.

- ^ Dann, Norman K. (2008). When we get to heaven : runaway slaves on the road to Peterboro. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. ISBN 9780975554845.

- ^ Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men, p. 265

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Renehan, Edward J. (1995). The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-59028-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sorin, Gerald (1970). The New York Abolitionists. A Case Study of Political Radicalism. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0837133084.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dann, Norman Kingsford (2021). Passionate Energies. The Gerrit and Ann Smith Family of Peterboro, New York Through a Century of Reform. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. ISBN 9781733089111.

- ^ a b Dann, Norman K. (2018). Peter Smith of Peterboro. Furs, Land, and Anguish. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. ISBN 9780692076514.

- ^ a b "Gerrit Smith. Biographical Information". New York History Net. 2012. Archived from the original on August 16, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ Dreaming of Timbuctoo [lesson plans], Adirondack History Museum, p. 7, archived from the original on April 24, 2022, retrieved April 3, 2022

- ^ "Gerrit Smith at Home". Belvidere Standard (Belvidere, Illinois). November 26, 1867. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Pula, James S.; Pula, Cheryl A., eds. (2010). "With Courage and Honor": Oneida County's Role in the Civil War. Utica, New York: Ethnic Heritage Studies Center, Utica College. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-9660363-7-4.

- ^ Smith, Gerrit (1846). Gerrit Smith's land auction. For sale, and the far greater share at public auction, about three quarters of a million of acres of land, lying in the State of New-York. Peterboro, New York.

- ^ Griffith, Elizabeth (1984). In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-19-503729-4.

- ^ New York History Net. "Historic Peterboro". Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ Outline History of Utica and Vicinity. Utica, New York: New Century Club of Utica. 1900. p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Sernett, Milton C. (1986). Abolition's axe : Beriah Green, Oneida Institute, and the Black freedom struggle. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815623700.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice (2011). On The Hill. A Bicentennial History of Hamilton College, 1812–2012. Clinton, New York: Hamilton College. p. 55. ISBN 9780615432090.

- ^ Gunston Hall Plantation. "Descendants of George Mason, 1629-1686". p. 48. Archived from the original on 2009-01-15.

- ^ a b c Smith, Gerrit (2011). Autobiography. New York History Net. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- ^ "Peterboro Manual Labor School". African Repository. 1834. pp. 312–313.

- ^ "Both sides! Speech of Mr. Gerrit Smith, In the Meeting of the New-York Anti-Slavery Society, held in Peterboro, October 22, 1835". Richmond Enquirer. November 20, 1835. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021 – via VirginiaChronicle.

- ^ a b Renahan, Jr., Edward J. (1995). The Secret Six. The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 051759028X.

- ^ List of delegates Archived 2018-11-17 at the Wayback Machine, 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention, 1840, Retrieved 2 August 2015

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Wellman, 2004, p. 176.

- ^ Claflin, Alta Blanche. Political parties in the United States 1800-1914 Archived 2020-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, New York Public Library, 1915, p. 50

- ^ "1848 Presidential General Election Results - New York". U.S. Election Atlas. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Smith, Gerrit (1851). The True Office of Civil Government. A Speech in the City of Troy. New York. Archived from the original on 2022-08-18. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vance, Laurence M. (Winter 2009). "Gerrit Smith: a radical nineteenth-century libertarian". Independent Review. 13 (3). Archived from the original on 2022-08-18. Retrieved 2022-07-24 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ^ a b Smith, Gerrit (1855). "Letter to the Voters of the Counties of Oswego and Madison". Speeches of Gerrit Smith in Congress [1853–1854]. New York: Mason Brothers.

- ^ a b Smith, Gerrit (27 Jun 1854). "Letter of Gerrit Smith". Daily National Era. Washington, D.C. p. 2. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Smith, Gerrit (1855) [August 7, 1854]. "Final letter to his constituents". Speeches of Gerrit Smith in Congress. New York: Mason Brothers. pp. 375–396.

- ^ "Gerrit Smith in Congress". Ashtabula Weekly Telegraph (Ashtabula, Ohio). November 5, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Proceedings of the Convention of Radical Political Abolitionists, held at Syracuse, N. Y., June 26th, 27th, and 28th, 1855, New York: Central Abolition Board, 1855, archived from the original on 2018-09-05, retrieved 2018-09-12

- ^ "RADICAL ABOLITION NATIONAL CONVENTION". Douglass' Monthly. October 1860. p. 352. Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-12.

- ^ "US President - Liberty (Union) National Convention". Our Campaigns. November 24, 2008. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ "Resignation of Gerrit Smith," Archived 2022-04-26 at the Wayback Machine New York Daily Times, vol. 3, whole no. 868 (June 29, 1854), pg. 1.

- ^ "Page Six of Brief history of prohibition and of the prohibition reform party". p. 6. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020.

- ^ "Page Twenty Three of Brief history of prohibition and of the prohibition reform party". p. 23. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020.

- ^ Sernett, Milton C. (2013), Biographical History, Syracuse University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center, archived from the original on 2020-10-29, retrieved 2022-04-06

- ^ "(Untitled)". The North Star. Rochester, New York. December 8, 1848. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022 – via accessible-archives.com.

- ^ a b "[Untitled]". New-York Tribune. 3 Aug 1857. p. 4. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Smith, Gerrit (10 Aug 1857). "Letter to the Editor". New-York Tribune. p. 3. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, January 2007

- ^ a b Harlow, Ralph Volney (1939). Gerrit Smith, Philanthropist and Reformer. New York: Russell & Russell. OCLC 772577603.

- ^ Heidler, David Stephen. (1996) Encyclopedia of the American Civil War p. 1812

- ^ "Speech of Governor Wise at Richmond. His Testimony to the Ubflinching Valor of the Troop. His Sketch of the Harper's Ferry Troubles". New York Daily Herald. 26 Oct 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Gerrit Smith and the Harper's Ferry Outbreak. A Visit to the Home of Gerrit Smith". New York Herald. November 2, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Condition of Gerrit Smith". Anti-Slavery Bugle. New Lisbon, Ohio. November 19, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2022-05-08. Retrieved 2022-05-08 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b c McKlulgan, John R.; Leveille, Madeleine (Fall 1985). "The 'Black Dream' of Gerrit Smith, New York Abolitionist". Syracuse University Library Associates Courier. Vol. 20, no. 2. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- ^ a b Harlow, Ralph Volney (Oct 1932). "Gerrit Smith and the John Brown Raid". American Historical Review. 38 (1): 32–60. doi:10.2307/1838063. JSTOR 1838063. Archived from the original on 2021-12-30. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ "Gerrit Smith's insanity — Attempt to commit suicide". National Era. Washington, D.C. 17 Nov 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Gerrit Smith and the Vigilant Association of the City of New-York. New York. 1860.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dann, Norman K. (2009). Practical Dreamer. Gerrit Smith and the campaign for Social Reform. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. ISBN 978-0-9755548-7-6.

- ^ Parks, Marlene K. (2017). New York Central College, 1849–1860. Vol. II, under Smith. (Book has no page numbers). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1548505752. OCLC 1035557718.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 262.

- ^ "Gerrit Smith Estate". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2008-01-17. Archived from the original on 2012-10-09.

- ^ LouAnn Wurst (September 21, 2001), National Historic Landmark Nomination: Gerrit Smith Estate (PDF), National Park Service, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-02

- ^ A student (November 8, 1834). "Letter to the editor". The Liberator. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ Wurst, LouAnn (September 2002). "'For the Means of Your Subsistence : : : Look Under God to Your Own Industry and Frugality': Life and Labor in Gerrit Smith's Peterboro". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 6 (3). Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ Williams, Peter; Ruggles, David; Allen, Wm. G.; Payne, D. A.; Bibb, Henry; Nell, William C.; Brown, Henry Box; Smith, James Boxer; Vashon, George B.; Crummell, Alexander; Pennington, J. W. C.; Myers, Stephen; Smith, J. Mccune; Langston, John Mercer; Whipper, Wm; Douglass, Frederick; Garnet, Henry Highland; Quarles, Benjamin (1942). Quarles, Benjamin (ed.). "Letters from Negro Leaders to Gerrit Smith". Journal of Negro History. 27 (4): 432–453, at p. 436. doi:10.2307/2715186. JSTOR 2715186. S2CID 150293241.

- ^ "Gerrit Smith". Rutland Daily Herald. Rutland (city), Vermont. February 4, 1878. p. 4. Archived from the original on April 26, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b MRC (Michele Combs?) (27 Mar 2013), Gerrit Smith Pamphlets and Broadsides Collection. A description of the collection at Syracuse University, archived from the original on 18 August 2022, retrieved 18 August 2022

- ^ "Reminiscent Matter Called to Mind by Hon. Gerrit Smith Miller's Gift to the University". The Adirondack Record–Elizabethtown Post. Gerrit Smith Miller was Gerrit Smith's grandson. January 10, 1929. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2021-07-26. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Gerrit Smith Papers, 1763-1924 (inclusive), Microfilming Corporation of America, 1974, OCLC 122452293

- ^ Gerrit Smith Papers, 1775-1924, Also at OCLC 21778731, Microfilming Corporation of America, 1974, OCLC 883513856

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ New York State Education, Department Division of Archives and History (1941). Calendar of the Gerrit Smith papers in the Syracuse University Library. Albany, New York: Works Progress Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-08-04. Retrieved 2022-08-04. 2 vols.

- ^ Gerrit Smith Pamphlets and Broadsides Collection 1793-1906, OCLC 953532298

- ^ a b Gerrit Smith. About this page, Gerrit Smith Virtual Museum, NY History Net, 2003, archived from the original on April 26, 2021, retrieved July 30, 2022

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Smith, Gerrit". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–262.

- This article incorporates public domain material from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

Further reading (most recent first)

edit- Bridgeford-Smith, Jan (September 2015). "Money, Morality, and Madness. Businessman Gerrit Smith gambled it all on John Brown". America's Civil War. 28 (4): 46–53.

- Martin, John H. (Fall 2005). "Gerrit Smith, Frederick Douglas and Harriet Tubman. The Anti-Slavery Impulse in the Burned-Over District". Crooked Lake Review. Saints, Sinners and Reformers: The Burned-Over District Re-Visited.

- Wellman, Judith (2004). The Road to Seneca Falls, Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02904-6

- Kruczek-Aaron, Hadley (September 2002). "Choice Flowers and Well-Ordered Tables: Struggling Over Gender in a Nineteenth-Century Household". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 6 (3): 173–185. doi:10.1023/A:1020333103453. JSTOR 20853002. S2CID 140772116.

- Stauffer, John (2002). The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00645-3.

- Renehan, Edward J. (1995). The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-59028-X.

- Sernett, Milton C. (Fall 1986). "Common Cause: The Antislavery Alliance of Gerrit Smith and Beriah Green". Syracuse University Library Associates Courier. Vol. 21, no. 2.

- Sanborn, Franklin Benjamin (July–December 1905). "A Concord Note-Book. Gerrit Smith and John Brown". The Critic: An Illustrated Monthly Review of Literature. New series. 44 (new series).

- Frothingham, Octavius Brooks, Gerrit Smith: A Biography (New York, 1879). ISBN 0-7812-2907-3.

- "Gerrit Smith and the Harper's Ferry Outbreak. A Visit to the Home of Gerrit Smith". New York Herald. November 2, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.