Garshāsp (Persian: گرشاسپ pronounced [gæɹ'ʃɒːsp]) was, in Persian mythology, the last Shah of the Pishdadian dynasty of Persia according to Shahnameh. He was a descendant of Zaav, ruling over the Persian Empire for about nine years. His name is shared with a monster-slaying hero in Iranian mythology. The Avestan form of his name is Kərəsāspa and in Middle Persian his name is Kirsāsp.

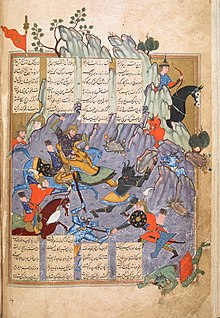

Garshasp is depicted as a dragonslayer in the Avesta. In Zoroastrian eschatology, Garshasp's resurrection was depicted. His role was to slay the monster Zahhak.

Kirsāsp in Zoroastrian literature

editIn the Zoroastrian religious text of the Avesta, Kərəsāspa appears as the slayer of ferocious monsters, including the Gandarəβa and the Aži Sruvara. In later Zoroastrian texts Kirsāsp is resurrected at the end of the world to defeat the monster Dahāg.

Kərəsāspa is the son of Θrita and belongs to the Sāma family. Θrita is originally the name of a deity; cf. the Vedic Trita.

Kirsāsp and the Aži Sruvara

editAccording to the Zoroastrian holy book, Avesta, Kərəsāspa once stopped on a hill to cook his midday meal. Unbeknownst to Kərəsāspa, the hill was actually the curved back of a sleeping dragon—the Aži Sruvara. As Kərəsāspa's fire began to crackle merrily, the heat from it caused the dragon to stir from its sleep and overturn the hero's kettle. The startled Kərəsāspa fled, but, on regaining his composure, returned to slay the dragon that had spoilt his lunch.

Later texts, the Persian Rivayat and Pahlavi Rivayat, add more details. According to them, the Az ī Srūwar was a dragon with horns, with huge eyes and ears, and teeth upon which the men it had eaten could be seen impaled. It was so long that Kərəsāspa ran along its back for half a day before he reached its head, struck it with his mace, and killed it.

Kirsāsp and the Gandarəβa

editAnother monster that Kirsāsp fought was the Gandarəβa, Middle Persian Gandarw. (This name is cognate to the Indic gandharva, but the exact way in which the word acquired its respective meanings in Indic and Iranian cultures is uncertain.) The Gandarw lived in the sea. It was also enormous, big enough to swallow twelve provinces in a single gulp, and so tall that when it stood up the deep sea reached only to its knee and its head was as high as the sun. The Gandarw pulled Kirsāsp into the ocean, and they fought for nine days. At last, Kirsāsp flayed the Gandarw and bound it with its own skin. Kirsāsp, weary from the combat, had his companion Axrūrag guard the Gandarw while he slept, but it proved too much for him – the Gandarw dragged Axrūrag and Kirsāsp's family into the sea. When Kirsāsp awakened, he rushed to the sea, freed the captives, and killed the Gandarw.

Kirsāsp and Dahāg

editThe Zoroastrian text called the Sūdgar tells that when the monster Dahāg, who is now bound in chains on Mount Damāvand, bursts free of his fetters at the end of the world, Kirsāsp will be resurrected (his corpse having been guarded from corruption) to destroy Dahāg and save the two thirds of the world that Dahāg has not devoured.

In Persian literature

editIn the Shāhnāma

editGarshasp or Garshasb was a king who ruled over parts of Greater Persia. Certain of his deeds are recounted in the epic poem Shāhnāma, which preserves, in late form, many of the legends and stories of Greater Persia. Garshasb had been ruling for more than 50 years when the royal family fell victim to black magic and were killed one after the other. Legend has it that there were a few members of the Garshasp clan who survived, but also that they remain enchanted to this day. Garshāsp is only tangentially mentioned in the Shāhnāma. There he appears as a distant ancestor of the hero Rostam, who lived at about the same time as King Fereydun. Garshāsp is the father of Narēmān, who is the father of Sām, father of Zāl, who is in turn Rostam's father.

In the Garshāspnāma

editGarshāsp received his own poetic treatment at the hands of Asadi Tusi, who wrote a Garshāspnāma about this hero.

In the Garshāspnāma, Garshāsp is the son of Esret (اثرط), the equivalent of the Avestan Θrita, and grandson of Sham (Avestan Sāma). His genealogy goes back through other characters not mentioned in the Avesta: Sham is the son of Tovorg (طورگ), son of Šēdasp, son of Tur, who was an illegitimate son of Jamshid by the daughter of Kurang, king of Zābolestān, begotten at the time that Jamshid had been deposed was fleeing from the forces of Zahhāk.

Zahhāk reigned for 1000 years, and so was still king at the time that Garshāsp was born. On one occasion when Zahhāk was traveling in Zābolestān, he saw Garshāsp and encourages him to slay a dragon that had emerged from the sea and settled on Mt. Šekāvand. Equipped with a special antidote against dragon-poison, and armed with special weapons, Garshāsp succeeds in killing the monster. Impressed by the child's prowess, Zahhāk now orders Garshāsp to India, where the king – a vassal of Zahhāk's – has been replaced by a rebel prince, Bahu, who does not acknowledge Zahhāk's rule. Garshāsp defeats the rebel and then stays in India for a while to observe its marvels and engage in philosophical discourse.

After returning from India, Garshāsp woos a princess of Rum, restores his father Esret to his throne in Zābol after the king of Kābol defeats him, and builds the city of Sistān. He has further anachronistic adventures in the Mediterranean, fighting in Kairouan and Córdoba.

When he returns to Iran, his father dies, and Garshāsp becomes king of Zābolestān. Although he has no son of his own, he adopts Narēmān as his heir, who would become Rostam's great-grandfather. The poem ends with another battle and dragon-slaying, followed by Garshāsp's death.

Rule

editBibliography

edit- Encyclopedia Iranica, "GARŠĀSP-NĀMA", FRANÇOIS DE BLOIS

- Ferdowsi Shahnameh. From the Moscow version. Mohammed Publishing. ISBN 964-5566-35-5