Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) and to the works they jointly created. The two men collaborated on fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado are among the best known.[1]

Gilbert, who wrote the libretti for these operas, created fanciful "topsy-turvy" worlds where each absurdity is taken to its logical conclusion: fairies rub elbows with British lords, flirting is a capital offence, gondoliers ascend to the monarchy, and pirates emerge as noblemen who have gone astray.[2] Sullivan, six years Gilbert's junior, composed the music, contributing memorable melodies[n 1] that could convey both humour and pathos.[n 2]

Their operas have enjoyed broad and enduring international success and are still performed frequently throughout the English-speaking world.[5][6] Gilbert and Sullivan introduced innovations in content and form that directly influenced the development of musical theatre through the 20th century.[7] The operas have also influenced political discourse, literature, film and television and have been widely parodied and pastiched by humorists. The producer Richard D'Oyly Carte brought Gilbert and Sullivan together and nurtured their collaboration. He built the Savoy Theatre in 1881 to present their joint works (which came to be known as the Savoy Operas) and founded the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which performed and promoted Gilbert and Sullivan's works for over a century.

Beginnings

editGilbert before Sullivan

editGilbert was born in London on 18 November 1836. His father, William, was a naval surgeon who later wrote novels and short stories, some of which included illustrations by his son.[8] In 1861, to supplement his income, the younger Gilbert began writing illustrated stories, poems and articles of his own, many of which would later be mined as inspiration for his plays and operas, particularly Gilbert's series of illustrated poems, the Bab Ballads.[9]

In the Bab Ballads and his early plays, Gilbert developed a unique "topsy-turvy" style in which humour was derived by setting up a ridiculous premise and working out its logical consequences, however absurd. Director and playwright Mike Leigh described the "Gilbertian" style as follows:

With great fluidity and freedom, [Gilbert] continually challenges our natural expectations. First, within the framework of the story, he makes bizarre things happen, and turns the world on its head. Thus the Learned Judge marries the Plaintiff, the soldiers metamorphose into aesthetes, and so on, and nearly every opera is resolved by a deft moving of the goalposts... His genius is to fuse opposites with an imperceptible sleight of hand, to blend the surreal with the real, and the caricature with the natural. In other words, to tell a perfectly outrageous story in a completely deadpan way.[2]

Gilbert developed his innovative theories on the art of stage direction, following the playwright and theatrical reformer Tom Robertson.[8] At the time Gilbert began writing, theatre in Britain was in disrepute.[10][n 3] Gilbert helped to reform and elevate the respectability of the theatre, especially beginning with his six short family-friendly comic operas, or "entertainments", for Thomas German Reed.[12]

At a rehearsal for one of these entertainments, Ages Ago, in 1870, the composer Frederic Clay introduced Gilbert to his friend, the young composer Arthur Sullivan.[13][n 4] Over the next year, before the two first collaborated, Gilbert continued to write humorous verse, stories and plays, including the comic operas Our Island Home (1870) and A Sensation Novel (1871), and the blank verse comedies The Princess (1870), The Palace of Truth (1870) and Pygmalion and Galatea (1871).[15]

Sullivan before Gilbert

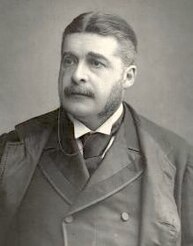

editSullivan was born in London on 13 May 1842. His father was a military bandmaster, and by the time Arthur had reached the age of eight, he was proficient with all the instruments in the band. In school he began to compose anthems and songs. In 1856, he received the first Mendelssohn Scholarship and studied at the Royal Academy of Music and then at Leipzig, where he also took up conducting. His graduation piece, completed in 1861, was a suite of incidental music to Shakespeare's The Tempest. Revised and expanded, it was performed at the Crystal Palace in 1862 and was an immediate sensation. He began building a reputation as England's most promising young composer, composing a symphony, a concerto, and several overtures, among them the Overture di Ballo, in 1870.[16]

His early major works for the voice included The Masque at Kenilworth (1864); an oratorio, The Prodigal Son (1869); and a dramatic cantata, On Shore and Sea (1871). He composed a ballet, L'Île Enchantée (1864) and incidental music for a number of Shakespeare plays. Other early pieces that were praised were his Symphony in E, Cello Concerto, and Overture in C (In Memoriam) (all three of which premiered in 1866).[17] These commissions were not sufficient to keep Sullivan afloat. He worked as a church organist and composed numerous hymns, popular songs, and parlour ballads.[18]

Sullivan's first foray into comic opera was Cox and Box (1866), written with the librettist F. C. Burnand for an informal gathering of friends. Public performance followed, with W. S. Gilbert (then writing dramatic criticism for the magazine Fun) saying that Sullivan's score "is, in many places, of too high a class for the grotesquely absurd plot to which it is wedded."[19] Nonetheless, it proved highly successful, and is still regularly performed today. Sullivan and Burnand's second opera, The Contrabandista (1867) was not as successful.[20]

Operas

editFirst collaborations

editThespis

editIn 1871, producer John Hollingshead brought Gilbert and Sullivan together to produce a Christmas entertainment, Thespis, at his Gaiety Theatre, a large West End house. The piece was an extravaganza in which the classical Greek gods, grown elderly, are temporarily replaced by a troupe of 19th-century actors and actresses, one of whom is the eponymous Thespis, the Greek father of the drama. Its mixture of political satire and grand opera parody mimicked Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld and La belle Hélène, which (in translation) then dominated the English musical stage.[21]

Thespis opened on Boxing Day and ran for 63 performances. It outran five of its nine competitors for the 1871 holiday season, and its run was extended beyond the length of a normal run at the Gaiety,[22] but no one at the time foresaw that this was the beginning of a great collaboration. Unlike the later Gilbert and Sullivan works, it was hastily prepared, and its nature was more risqué, like Gilbert's earlier burlesques, with a broader style of comedy that allowed for improvisation by the actors. Two of the male characters were played by women, whose shapely legs were put on display in a fashion that Gilbert later condemned.[23] The musical score to Thespis was never published and is now lost, except for one song that was published separately, a chorus that was re-used in The Pirates of Penzance, and the Act II ballet music.[21]

Over the next three years, Gilbert and Sullivan did not have occasion to work together again, but each man became more eminent in his field. Gilbert worked with Frederic Clay on Happy Arcadia (1872) and Alfred Cellier on Topsyturveydom (1874) and wrote The Wicked World (1873), Sweethearts (1874) and several other libretti, farces, extravaganzas, fairy comedies, dramas and adaptations. Sullivan completed his Festival Te Deum (1872); another oratorio, The Light of the World (1873); his only song cycle, The Window; or, The Song of the Wrens (1871); incidental music to The Merry Wives of Windsor (1874); and more songs, parlour ballads, and hymns, including "Onward, Christian Soldiers" (1872). At the same time, the audience for theatre was growing because of the rapidly expanding British population; improvement in education and the standard of living, especially of the middle class; improving public transport; and installation of street lighting, which made travel home from the theatre safer.[24] The number of pianos manufactured in England doubled between 1870 and 1890 as more people began to play parlour music at home and more theatres and concert halls opened.[25][n 5]

Trial by Jury

editIn 1874, Gilbert wrote a short libretto on commission from producer-conductor Carl Rosa, whose wife would have played the leading role, but her death in childbirth cancelled the project. Not long afterwards, Richard D'Oyly Carte was managing the Royalty Theatre and needed a short opera to be played as an afterpiece to Offenbach's La Périchole. Carte knew about Gilbert's libretto for Rosa and suggested that Sullivan write a score for it. Gilbert read the piece to Sullivan in February 1875, and the composer was delighted with it; Trial by Jury was composed and staged in a matter of weeks.[n 6]

The piece is one of Gilbert's humorous spoofs of the law and the legal profession, based on his short experience as a barrister. It concerns a breach of promise of marriage suit. The defendant argues that damages should be slight, since "he is such a very bad lot," while the plaintiff argues that she loves the defendant fervently and seeks "substantial damages." After much argument, the judge resolves the case by marrying the lovely plaintiff himself. With Sullivan's brother, Fred, as the Learned Judge, the opera was a runaway hit, outlasting the run of La Périchole. Provincial tours and productions at other theatres quickly followed.[29]

Fred Sullivan was the prototype for the "patter" (comic) baritone roles in the later operas. F. C. Burnand wrote that he "was one of the most naturally comic little men I ever came across. He, too, was a first-rate practical musician.... As he was the most absurd person, so was he the very kindliest...."[30] Fred's creation would serve as a model for the rest of the collaborators' works, and each of them has a crucial comic little man role, as Burnand had put it. The "patter" baritone (or "principal comedian", as these roles later were called) would often assume the leading role in Gilbert and Sullivan's comic operas, and was usually allotted the speedy patter songs.[31]

After the success of Trial by Jury, Gilbert and Sullivan were suddenly in demand to write more operas together. Over the next two years, Richard D'Oyly Carte and Carl Rosa were two of several theatrical managers who negotiated with the team but were unable to come to terms. Carte proposed a revival of Thespis for the 1875 Christmas season, which Gilbert and Sullivan would have revised, but he was unable to obtain financing for the project. In early 1876, Carte requested that Gilbert and Sullivan create another one-act opera on the theme of burglars, but this was never completed.[n 7]

Early successes

editThe Sorcerer

editCarte's real ambition was to develop an English form of light opera that would displace the bawdy burlesques and badly translated French operettas then dominating the London stage. He assembled a syndicate and formed the Comedy Opera Company, with Gilbert and Sullivan commissioned to write a comic opera that would serve as the centrepiece for an evening's entertainment.[33]

Gilbert found a subject in one of his own short stories, "The Elixir of Love", which concerned the complications arising when a love potion is distributed to all the residents of a small village. The leading character was a Cockney businessman who happened to be a sorcerer, a purveyor of blessings (not much called for) and curses (very popular). Gilbert and Sullivan were tireless taskmasters, seeing to it that The Sorcerer (1877) opened as a fully polished production, in marked contrast to the under-rehearsed Thespis.[34] While The Sorcerer won critical acclaim, it did not duplicate the success of Trial by Jury. Nevertheless, it ran for more than six months, and Carte and his syndicate were sufficiently encouraged to commission another full-length opera from the team.[35]

H.M.S. Pinafore

editGilbert and Sullivan scored their first international hit with H.M.S. Pinafore (1878), satirising the rise of unqualified people to positions of authority and poking good-natured fun at the Royal Navy and the English obsession with social status (building on a theme introduced in The Sorcerer, love between members of different social classes). As with many of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, a surprise twist changes everything dramatically near the end of the story.[36]

Gilbert oversaw the designs of sets and costumes, and he directed the performers on stage.[n 8] He sought realism in acting, shunned self-conscious interaction with the audience, and insisted on a standard of characterisation in which the characters were never aware of their own absurdity.[38] He insisted that his actors know their words perfectly and obey his stage directions, which was something new to many actors of the day.[38] Sullivan personally oversaw the musical preparation. The result was a crispness and polish new to the English musical theatre.[n 9] Jessie Bond wrote later:

H.M.S. Pinafore ran in London for 571 performances,[41] an exceptional run for the period.[n 10] Hundreds of unauthorised, or "pirated", productions of Pinafore appeared in America.[43] During the run of Pinafore, Richard D'Oyly Carte split up with his former investors. The disgruntled former partners, who had invested in the production with no return, staged a public fracas, sending a group of thugs to seize the scenery during a performance. Stagehands managed to ward off their backstage attackers.[44] This event cleared the way for Carte, in alliance with Gilbert and Sullivan, to form the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which then produced all their succeeding operas.[45]

The libretto of H.M.S. Pinafore relied on stock character types, many of which were familiar from European opera (and some of which grew out of Gilbert's earlier association with the German Reeds): the heroic protagonist (tenor) and his love-interest (soprano); the older woman with a secret or a sharp tongue (contralto); the baffled lyric baritone – the girl's father; and a classic villain (bass-baritone). Gilbert and Sullivan added the element of the comic patter-singing character. With the success of H.M.S. Pinafore, the D'Oyly Carte repertory and production system was cemented, and each opera would make use of these stock character types. Before The Sorcerer, Gilbert had constructed his plays around the established stars of whatever theatre he happened to be writing for, as had been the case with Thespis and Trial by Jury. Building on the team he had assembled for The Sorcerer, Gilbert no longer hired stars; he created them. He and Sullivan selected the performers, writing their operas for ensemble casts rather than individual stars.[46]

The repertory system ensured that the comic patter character who performed the role of the sorcerer, John Wellington Wells, would become the ruler of the Queen's navy as Sir Joseph Porter in H.M.S. Pinafore, then join the army as Major-General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance, and so on. Similarly, Mrs. Partlet in The Sorcerer transformed into Little Buttercup in Pinafore, then into Ruth, the piratical maid-of-all-work in Pirates. Relatively unknown performers whom Gilbert and Sullivan engaged early in the collaboration would stay with the company for many years, becoming stars of the Victorian stage. These included George Grossmith, the principal comic; Rutland Barrington, the lyric baritone; Richard Temple, the bass-baritone; and Jessie Bond, the mezzo-soprano soubrette.[46]

The Pirates of Penzance

editThe Pirates of Penzance (New Year's Eve, 1879) also poked fun at grand opera conventions, sense of duty, family obligation, the "respectability" of civilisation and the peerage, and the relevance of a liberal education. The story also revisits Pinafore's theme of unqualified people in positions of authority, in the person of the "modern Major-General" who has up-to-date knowledge about everything except the military. The Major-General and his many daughters escape from the tender-hearted Pirates of Penzance, who are all orphans, on the false plea that he is an orphan himself. The pirates learn of the deception and re-capture the Major-General, but when it is revealed that the pirates are all peers, the Major-General bids them: "resume your ranks and legislative duties, and take my daughters, all of whom are beauties!"[47]

The piece premiered in New York rather than London, in an (unsuccessful) attempt to secure the American copyright,[48] and was another big success with both critics and audiences.[49] Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte tried for many years to control the American performance copyrights over their operas, without success.[43][50] Nevertheless, Pirates was a hit both in New York, again spawning numerous imitators, and then in London, and it became one of the most frequently performed, translated and parodied Gilbert and Sullivan works, also enjoying successful 1981 Broadway[51] and 1982 West End revivals by Joseph Papp that continue to influence productions of the opera.[52]

In 1880, Sullivan's cantata The Martyr of Antioch premiered at the Leeds Triennial Music Festival, with a libretto adapted by Sullivan and Gilbert from an 1822 epic poem by Henry Hart Milman concerning the 3rd-century martyrdom of St. Margaret of Antioch. Sullivan became the conductor of the Leeds festival beginning in 1880 and conducted the performance. The Carl Rosa Opera Company staged the cantata as an opera in 1898.[53]

Savoy Theatre opens

editPatience

editPatience (1881) satirised the aesthetic movement in general and its colourful poets in particular, combining aspects of A. C. Swinburne, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Oscar Wilde, James McNeill Whistler and others in the rival poets Bunthorne and Grosvenor. Grossmith, who created the role of Bunthorne, based his makeup, wig and costume on Swinburne and especially Whistler, as seen in the adjacent photograph.[54] The work also lampoons male vanity and chauvinism in the military. The story concerns two rival aesthetic poets, who attract the attention of the young ladies of the village, formerly engaged to the members of a cavalry regiment. But both poets are in love with Patience, the village milkmaid, who detests one of them and feels that it is her duty to avoid the other despite her love for him. Richard D'Oyly Carte was the booking manager for Oscar Wilde, a then lesser-known proponent of aestheticism, and dispatched him on an American lecture tour in conjunction with the opera's U.S. run, so that American audiences might better understand what the satire was all about.[55]

During the run of Patience, Carte built the large, modern Savoy Theatre, which became the partnership's permanent home. It was the first theatre (and the world's first public building) to be lit entirely by electric lighting.[56] Patience moved into the Savoy after six months at the Opera Comique and ran for a total of 578 performances, surpassing the run of H.M.S. Pinafore.[57]

Iolanthe

editIolanthe (1882) was the first of the operas to open at the Savoy. The fully electric Savoy made possible numerous special effects, such as sparkling magic wands for the female chorus of fairies. The opera poked fun at English law and the House of Lords and made much of the war between the sexes. The critics felt that Sullivan's work in Iolanthe had taken a step forward. The Daily Telegraph commented, "The composer has risen to his opportunity, and we are disposed to account Iolanthe his best effort in all the Gilbertian series."[58] Similarly, The Theatre judged that "the music of Iolanthe is Dr Sullivan's chef d'oeuvre. The quality throughout is more even, and maintained at a higher standard, than in any of his earlier works..."[59]

Iolanthe is one of several of Gilbert's works, including The Wicked World (1873), Broken Hearts (1875), Princess Ida (1884) and Fallen Fairies (1909), where the introduction of men and "mortal love" into a tranquil world of women wreaks havoc with the status quo.[60] Gilbert had created several "fairy comedies" at the Haymarket Theatre in the early 1870s. These plays, influenced by the fairy work of James Planché, are founded upon the idea of self-revelation by characters under the influence of some magic or some supernatural interference.[61]

In 1882, Gilbert had a telephone installed in his home and at the prompt desk at the Savoy Theatre so that he could monitor performances and rehearsals from his home study. Gilbert had referred to the new technology in Pinafore in 1878, only two years after the device was invented and before London even had telephone service. Sullivan had one installed as well, and on 13 May 1883, at a party to celebrate the composer's 41st birthday, the guests, including the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), heard a direct relay of parts of Iolanthe from the Savoy. This was probably the first live "broadcast" of an opera.[62]

During the run of Iolanthe, in 1883, Sullivan was knighted by Queen Victoria. Although it was the operas with Gilbert that had earned him the broadest fame, the honour was conferred for his services to serious music. The musical establishment, and many critics, believed that this should put an end to his career as a composer of comic opera – that a musical knight should not stoop below oratorio or grand opera.[63] Sullivan, despite the financial security of writing for the Savoy, increasingly viewed his work with Gilbert as unimportant, beneath his skills, and repetitious. Furthermore, he was unhappy that he had to simplify his music to ensure that Gilbert's words could be heard. But paradoxically, in February 1883, just after Iolanthe opened, Sullivan had signed a five-year agreement with Gilbert and Carte requiring him to produce a new comic opera on six months' notice.[64]

Princess Ida

editPrincess Ida (1884) spoofed women's education and male chauvinism and continued the theme from Iolanthe of the war between the sexes. The opera is based on Tennyson's poem The Princess: A Medley. Gilbert had written a blank verse farce based on the same material in 1870, called The Princess, and he reused a good deal of the dialogue from his earlier play in the libretto of Princess Ida. Ida is the only Gilbert and Sullivan work with dialogue entirely in blank verse and is also the only one of their works in three acts. Lillian Russell had been engaged to create the title role, but Gilbert did not believe that she was dedicated enough, and when she missed a rehearsal, he dismissed her.[65]

Princess Ida was the first of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas that, by the partnership's previous standards, was not a success. A particularly hot summer in London did not help ticket sales. The piece ran for a comparatively short 246 performances and was not revived in London until 1919. Sullivan had been satisfied with the libretto, but two months after Ida opened, Sullivan told Carte that "it is impossible for me to do another piece of the character of those already written by Gilbert and myself."[64] As Princess Ida showed signs of flagging, Carte realised that, for the first time in the partnership's history, no new opera would be ready when the old one closed. On 22 March 1884, he gave Gilbert and Sullivan contractual notice that a new opera would be required in six months' time.[66] In the meantime, when Ida closed, Carte produced a revival of The Sorcerer.[67]

Dodging the magic lozenge

editThe Mikado

editThe most successful of the Savoy Operas was The Mikado (1885), which made fun of English bureaucracy, thinly disguised by a Japanese setting. Gilbert initially proposed a story for a new opera about a magic lozenge that would change the characters, which Sullivan found artificial and lacking in "human interest and probability", as well as being too similar to their earlier opera, The Sorcerer.[n 11] As dramatised in the film Topsy-Turvy, the author and composer were at an impasse until 8 May 1884, when Gilbert dropped the lozenge idea and agreed to provide a libretto without any supernatural elements.[n 12]

The story focuses on a "cheap tailor", Ko-Ko, who is promoted to the position of Lord High Executioner of the town of Titipu. He loves his ward, Yum-Yum, but she loves a musician, who is really the son of the emperor of Japan (the Mikado) and who is in disguise to escape the attentions of the elderly and amorous Katisha. The Mikado has decreed that executions must resume without delay in Titipu. When news arrives that the Mikado will be visiting the town, Ko-Ko assumes that he is coming to ascertain whether Ko-Ko has carried out the executions. Too timid to execute anyone, Ko-Ko cooks up a conspiracy to misdirect the Mikado, which goes awry. Eventually, Ko-Ko must persuade Katisha to marry him to save his own life and the lives of the other conspirators.

With the opening of trade between England and Japan, Japanese imports, art and styles became fashionable, and a Japanese village exhibition opened in Knightsbridge, London, making the time ripe for an opera set in Japan. Gilbert said, "I cannot give you a good reason for our... piece being laid in Japan. It... afforded scope for picturesque treatment, scenery and costume, and I think that the idea of a chief magistrate, who is... judge and actual executioner in one, and yet would not hurt a worm, may perhaps please the public."[70]

Setting the opera in Japan, an exotic locale far away from Britain, allowed Gilbert and Sullivan to satirise British politics and institutions more freely by clothing them in superficial Japanese trappings. Gilbert wrote, "The Mikado of the opera was an imaginary monarch of a remote period and cannot by any exercise of ingenuity be taken to be a slap on an existing institution."[71] G. K. Chesterton compared it to Swift's Gulliver's Travels: "Gilbert pursued and persecuted the evils of modern England till they had literally not a leg to stand on, exactly as Swift did... I doubt if there is a single joke in the whole play that fits the Japanese. But all the jokes in the play fit the English. ... About England Pooh-bah is something more than a satire; he is the truth."[72] Several of the later operas are similarly set in foreign or fictional locales, including The Gondoliers, Utopia, Limited and The Grand Duke.[73]

The Mikado became the partnership's longest-running hit, enjoying 672 performances at the Savoy Theatre, and surpassing the runs of Pinafore and Patience. It remains the most frequently performed Savoy Opera.[74] It has been translated into numerous languages and is one of the most frequently played musical theatre pieces in history.[75]

Ruddigore

editRuddigore (1887), a topsy-turvy take on Victorian melodrama, was less successful than most of the earlier collaborations with a run of 288 performances. The original title, Ruddygore, together with some of the plot devices, including the revivification of ghosts, drew negative comments from critics.[76][n 13] Gilbert and Sullivan respelled the title and made a number of changes and cuts.[78] Nevertheless, the piece was profitable,[79] and the reviews were not all bad. For instance, The Illustrated London News praised the work and both Gilbert and, especially, Sullivan: "Sir Arthur Sullivan has eminently succeeded alike in the expression of refined sentiment and comic humour. In the former respect, the charm of graceful melody prevails; while, in the latter, the music of the most grotesque situations is redolent of fun."[80] Further changes were made, including a new overture, when Rupert D'Oyly Carte revived Ruddigore after the First World War, and the piece was regularly performed by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company thereafter.[81]

Some of the plot elements of Ruddigore were introduced by Gilbert in his earlier one-act opera, Ages Ago (1869), including the tale of the wicked ancestor and the device of the ghostly ancestors stepping out of their portraits.[82][83] When Ruddigore closed, no new opera was ready. Gilbert again proposed a version of the "lozenge" plot for their next opera, and Sullivan reiterated his reluctance to set it.[84] While the two men worked out their artistic differences, and Sullivan finished other obligations, Carte produced revivals of such old favourites as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado.[85]

The Yeomen of the Guard

editThe Yeomen of the Guard (1888), their only joint work with a serious ending, concerns a pair of strolling players – a jester and a singing girl – who are caught up in a risky intrigue at the Tower of London during the 16th century. The dialogue, though in prose, is quasi-Early Modern English in style, and there is no satire of British institutions. For some of the plot elements, Gilbert had reached back to his 1875 tragedy, Broken Hearts. The Times praised the libretto: "It should... be acknowledged that Mr. Gilbert has earnestly endeavoured to leave familiar grooves and rise to higher things".[86] Although not a grand opera, the new libretto provided Sullivan with the opportunity to write his most ambitious theatre score to date. The critics, who had recently lauded the composer for his successful oratorio, The Golden Legend, considered the score to Yeomen to be Sullivan's finest, including its overture, which was written in sonata form, rather than as a sequential pot-pourri of tunes from the opera, as in most of his other overtures. The Daily Telegraph said:

The accompaniments... are delightful to hear, and especially does the treatment of the woodwind compel admiring attention. Schubert himself could hardly have handled those instruments more deftly, written for them more lovingly.... We place the songs and choruses in The Yeomen of the Guard before all his previous efforts of this particular kind. Thus the music follows the book to a higher plane, and we have a genuine English opera....[87]

Yeomen was a hit, running for over a year, with strong New York and touring productions. During the run, on 12 March 1889, Sullivan wrote to Gilbert,

I have lost the liking for writing comic opera, and entertain very grave doubts as to my power of doing it... You say that in a serious opera, you must more or less sacrifice yourself. I say that this is just what I have been doing in all our joint pieces, and, what is more, must continue to do in comic opera to make it successful.[88]

Sullivan insisted that the next opera must be a grand opera. Gilbert did not feel that he could write a grand opera libretto, but he offered a compromise that Sullivan eventually accepted. The two would write a light opera for the Savoy, and at the same time, Sullivan a grand opera (Ivanhoe) for a new theatre that Carte was constructing to present British opera. After a brief impasse over the choice of subject, Sullivan accepted an idea connected with Venice and Venetian life, as "this seemed to me to hold out great chances of bright colour and taking music."[89]

The Gondoliers

editThe Gondoliers (1889) takes place partly in Venice and partly in a fictional kingdom ruled by a pair of gondoliers who attempt to remodel the monarchy in a spirit of "republican equality."[90] Gilbert recapitulates a number of his earlier themes, including the satire of class distinctions figuring in many of his earlier librettos. The libretto also reflects Gilbert's fascination with the "Stock Company Act", highlighting the absurd convergence of natural persons and legal entities, which plays an even larger part in the next opera, Utopia, Limited. Press accounts were almost entirely favourable. The Illustrated London News reported:

...Gilbert has returned to the Gilbert of the past, and everyone is delighted. He is himself again. The Gilbert of the Bab Ballads, the Gilbert of whimsical conceit, inoffensive cynicism, subtle satire, and playful paradox; the Gilbert who invented a school of his own, who in it was schoolmaster and pupil, who has never taught anybody but himself, and is never likely to have any imitator – this is the Gilbert the public want to see, and this is the Gilbert who on Saturday night was cheered till the audience was weary of cheering any more.[91]

Sullivan's old collaborator on Cox and Box (later the editor of Punch magazine), F. C. Burnand, wrote to the composer: "Magnificento!...I envy you and W.S.G. being able to place a piece like this on the stage in so complete a fashion."[91] The opera enjoyed a run longer than any of their other joint works except for H.M.S. Pinafore, Patience and The Mikado. There was a command performance of The Gondoliers for Queen Victoria and the royal family at Windsor Castle in 1891, the first Gilbert and Sullivan opera to be so honoured. The Gondoliers was Gilbert and Sullivan's last great success.[92]

Carpet quarrel

editThough Gilbert and Sullivan's working relationship was mostly cordial and even friendly, it sometimes became strained, especially during their later operas, partly because each man saw himself as allowing his work to be subjugated to the other's, and partly caused by the opposing personalities of the two: Gilbert was often confrontational and notoriously thin-skinned (though prone to acts of extraordinary kindness), while Sullivan eschewed conflict.[93] Gilbert imbued his libretti with absurdist "topsy-turvy" situations in which the social order was turned upside down. After a time, these subjects were often at odds with Sullivan's desire for realism and emotional content.[94] Gilbert's political satire often poked fun at the wealthy and powerful whom Sullivan sought out for friendship and patronage.[95]

Gilbert and Sullivan disagreed several times over the choice of a subject. After each of Princess Ida and Ruddigore, which were less successful than their seven other operas from H.M.S. Pinafore to The Gondoliers, Sullivan asked to leave the partnership, saying that he found Gilbert's plots repetitive and that the operas were not artistically satisfying to him.[64] While the two artists worked out their differences in those cases, Carte kept the Savoy open with revivals of their earlier works. On each occasion, after a few months' pause, Gilbert responded with a libretto that met Sullivan's objections, and the partnership was able to continue.[64]

In April 1890, during the run of The Gondoliers, Gilbert challenged Carte over the expenses of the production. Among other items to which Gilbert objected, Carte had charged the cost of a new carpet for the Savoy Theatre lobby to the partnership.[96] Gilbert believed that this was a maintenance expense that should be charged to Carte alone. Gilbert confronted Carte, who refused to reconsider the accounts. Gilbert stormed out and wrote to Sullivan that "I left him with the remark that it was a mistake to kick down the ladder by which he had risen".[64] Helen Carte wrote that Gilbert had addressed Carte "in a way that I should not have thought you would have used to an offending menial".[97] On 5 May 1890, Gilbert wrote to Sullivan: "The time for putting an end to our collaboration has at last arrived. … I am writing a letter to Carte ... giving him notice that he is not to produce or perform any of my libretti after Christmas 1890."[64] As biographer Andrew Crowther has explained:

After all, the carpet was only one of a number of disputed items, and the real issue lay not in the mere money value of these things, but in whether Carte could be trusted with the financial affairs of Gilbert and Sullivan. Gilbert contended that Carte had at best made a series of serious blunders in the accounts, and at worst deliberately attempted to swindle the others. It is not easy to settle the rights and wrongs of the issue at this distance, but it does seem fairly clear that there was something very wrong with the accounts at this time. Gilbert wrote to Sullivan on 28 May 1891, a year after the end of the "Quarrel", that Carte had admitted "an unintentional overcharge of nearly £1,000 in the electric lighting accounts alone.[64]

Things soon degraded, Gilbert lost his temper with his partners and brought a lawsuit against Carte.[98] Sullivan supported Carte by making an affidavit erroneously stating that there were minor legal expenses outstanding from a battle Gilbert had in 1884 with Lillian Russell when, in fact, those expenses had already been paid.[99] When Gilbert discovered this, he asked for a retraction of the affidavit; Sullivan refused.[98] Gilbert felt it was a moral issue and could not look past it. Sullivan felt that Gilbert was questioning his good faith, and in any event Sullivan had other reasons to stay in Carte's good graces: Carte was building a new theatre, the Royal English Opera House (now the Palace Theatre), to produce Sullivan's only grand opera, Ivanhoe.[64] After The Gondoliers closed in 1891, Gilbert withdrew the performance rights to his libretti, vowing to write no more operas for the Savoy.[100]

Gilbert next wrote The Mountebanks with Alfred Cellier and the flop Haste to the Wedding with George Grossmith, and Sullivan wrote Haddon Hall with Sydney Grundy.[101] Gilbert eventually won the lawsuit, but his actions and statements had been hurtful to his partners. Nevertheless, the partnership had been so profitable that, after the financial failure of the Royal English Opera House, Carte and his wife sought to reunite the author and composer.[100] In late 1891, after many failed attempts at reconciliation, Gilbert and Sullivan's music publisher, Tom Chappell, stepped in to mediate between two of his most profitable artists, and within two weeks he had succeeded, eventually leading to two further collaborations between Gilbert and Sullivan.[102]

Last works

editUtopia, Limited (1893), their penultimate opera, was a very modest success, and their last, The Grand Duke (1896), was an outright failure.[103] Neither work entered the canon of regularly performed Gilbert and Sullivan works until the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company made the first complete professional recordings of the two operas in the 1970s. Gilbert had also offered Sullivan another libretto, His Excellency (1894), but Gilbert's insistence on casting Nancy McIntosh, his protege from Utopia, led to Sullivan's refusal, and His Excellency was instead composed by F. Osmond Carr.[104] Meanwhile, the Savoy Theatre continued to revive the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, in between new pieces, and D'Oyly Carte touring companies also played them in repertory.[105]

After The Grand Duke, the partners saw no reason to work together again. A last unpleasant misunderstanding occurred in 1898. At the premiere of Sullivan's opera The Beauty Stone on 28 May, Gilbert arrived at the Savoy Theatre with friends, assuming that Sullivan had reserved some seats for him. Instead, he was informed that Sullivan objected to his presence. The composer later denied that this was true.[96] The last time they met was at the Savoy Theatre on 17 November 1898 at the celebration of the 21st anniversary of the first performance of The Sorcerer. They did not speak to each other.[106] Sullivan, by this time in exceedingly poor health, died in 1900, although to the end he continued to write new comic operas for the Savoy with other librettists, most successfully with Basil Hood in The Rose of Persia (1899). Gilbert also wrote several works, some with other collaborators, in the 1890s. By the time of Sullivan's death in 1900, Gilbert wrote that any memory of their rift had been "completely bridged over," and "the most cordial relations existed between us."[96][107] He stated that "Sullivan ... because he was a composer of the rarest genius, was as modest and as unassuming as a neophyte should be, but seldom is...I remember all that he has done for me in allowing his genius to shed some of its lustre upon my humble name."[107]

Richard D'Oyly Carte died in 1901, and his widow, Helen, continued to direct the activities of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company at the Savoy and on tour. Gilbert went into semi-retirement, although he continued to direct revivals of the Savoy Operas and wrote new plays occasionally. Between 1906 and 1909, he assisted Mrs. Carte in staging two repertory seasons at the Savoy Theatre. These were very popular and revived interest in the works.[108] Gilbert was knighted during the first repertory season.[109] After Sullivan's death, Gilbert wrote only one more comic opera, Fallen Fairies (1909; music by Edward German), which was not a success.[96][110]

Legacy and assessment

editGilbert died in 1911, and Richard's son, Rupert D'Oyly Carte, took over the opera company upon his step-mother's death in 1913. His daughter, Bridget, inherited the company upon his death in 1948. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company toured nearly year-round, except for its many London seasons and foreign tours, performing exclusively the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, until it closed in 1982. During the 20th century, the company gave well over 35,000 performances.[111][112] The Savoy operas, from the beginning, were produced extensively in North America and Australasia, and soon afterwards in Germany, Russia, and elsewhere in Europe and around the world.[113]

In 1922, Sir Henry Wood explained the enduring success of the collaboration as follows:

Sullivan has never had an equal for brightness and drollery, for humour without coarseness and without vulgarity, and for charm and grace. His orchestration is delightful: he wrote with full understanding of every orchestral voice. Above all, his music is perfectly appropriate to the words of which it is the setting.... He found the right, the only cadences to fit Gilbert's happy and original rhythms, and to match Gilbert's fun or to throw Gilbert's frequent irony, pointed although not savage, into relief. Sullivan's music is much more than the accompaniment of Gilbert's libretti, just as Gilbert's libretti are far more than words to Sullivan's music. We have two masters who are playing a concerto. Neither is subordinate to the other; each gives what is original, but the two, while neither predominates, are in perfect correspondence. This rare harmony of words and music is what makes these operas entirely unique. They are the work not of a musician and his librettist nor of a poet and one who sets his words to music, but of two geniuses.[114]

G. K. Chesterton similarly praised the combination of the two artists, anticipating the operas' success into the "remote future". He wrote that Gilbert's satire was "too intelligent to be intelligible" by itself, and that perhaps only Sullivan could have given "wings to his words ... in exactly the right degree frivolous and exactly the right degree fastidious. [The words'] precise degree of levity and distance from reality ... seemed to be expressed ... in the very notes of the music; almost ... in the note of the laughter that followed it."[115] In 1957, a review in The Times gave this rationale for "the continued vitality of the Savoy operas":

[T]hey were never really contemporary in their idiom.... Gilbert and Sullivan's [world], from the first moment was obviously not the audience's world, [it was] an artificial world, with a neatly controlled and shapely precision which has not gone out of fashion – because it was never in fashion in the sense of using the fleeting conventions and ways of thought of contemporary human society.... For this, each partner has his share of credit. The neat articulation of incredibilities in Gilbert's plots is perfectly matched by his language.... His dialogue, with its primly mocking formality, satisfies both the ear and the intelligence. His verses show an unequalled and very delicate gift for creating a comic effect by the contrast between poetic form and prosaic thought and wording.... How deliciously [his lines] prick the bubble of sentiment.... [Of] equal importance... Gilbert's lyrics almost invariably take on extra point and sparkle when set to Sullivan's music.... Sullivan's tunes, in these operas, also exist in a make-believe world of their own.... [He is] a delicate wit, whose airs have a precision, a neatness, a grace, and a flowing melody.... The two men together remain endlessly and incomparably delightful.... Light, and even trifling, though [the operas] may seem upon grave consideration, they yet have the shapeliness and elegance that can make a trifle into a work of art.[116]

Because of the unusual success of the operas, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company were able, from the start, to license the works to other professional companies, such as the J. C. Williamson Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Company, and to amateur troupes. For almost a century, until the British copyrights expired at the end of 1961, and even afterwards, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company influenced productions of the operas worldwide, creating a "performing tradition" for most of the operas that is still referred to today by many directors, both amateur and professional.[117] Indeed, Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte had an important influence on amateur theatre. Cellier and Bridgeman wrote in 1914 that, prior to the creation of the Savoy operas, amateur actors were treated with contempt by professionals. After the formation of amateur Gilbert and Sullivan companies in the 1880s licensed to perform the operas, professionals recognised that the amateur performing groups "support the culture of music and the drama. They are now accepted as useful training schools for the legitimate stage, and from the volunteer ranks have sprung many present-day favourites."[118] Cellier and Bridgeman attributed the rise in quality and reputation of the amateur groups largely to "the popularity of, and infectious craze for performing, the Gilbert and Sullivan operas".[119] The National Operatic and Dramatic Association (NODA) was founded in 1899. It reported, in 1914, that nearly 200 British troupes were performing Gilbert and Sullivan that year, constituting most of the amateur companies in the country (this figure included only the societies that were members of NODA). The association further reported that almost 1,000 performances of the Savoy operas had been given in Britain that year, many of them to benefit charities.[120] Cellier and Bridgeman noted that strong amateur groups were performing the operas in places as far away as New Zealand.[121] In the U.S., and elsewhere where British copyrights on the operas were not enforced, both professional and amateur companies performed the works throughout the 20th century – the Internet Broadway Database counts about 150 productions on Broadway alone from 1900 to 1960. The Savoy Company, an amateur group formed in 1901 in Philadelphia, continues to perform today.[122][123] In 1948, Life magazine reported that about 5,000 performances of Gilbert and Sullivan operas were given annually in the US, exceeding the number of performances of Shakespeare plays.[124]

After the copyrights on the operas expired, other professional companies were free to perform and record the operas, even in Britain and The Commonwealth. Many performing companies arose to produce the works, such as Gilbert and Sullivan for All in Britain,[125] and existing companies, such as English National Opera, Carl Rosa Opera Company and Australian Opera, added Gilbert and Sullivan to their repertories.[126] The operas were presented by professional repertory companies in the US, including the competing Light Opera of Manhattan and NYGASP in New York City. In 1980, a Broadway and West End production of Pirates produced by Joseph Papp brought new audiences to Gilbert and Sullivan. Between 1988 and 2003, a new iteration of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company revived the operas on tour and in the West End.[127] Today, various professional repertory companies, such as NYGASP, Opera della Luna, National Gilbert & Sullivan Opera Company, Opera North, Ohio Light Opera, Scottish Opera and other regional opera companies,[128] and numerous amateur societies, churches, schools and universities continue to produce the works.[6][129] The most popular G&S works also continue to be performed from time to time by major opera companies,[130][n 14] and recordings of the operas, overtures and songs from the operas continue to be released.[132][133] Since 1994, the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival has been held every August in England (except 2020), with some two dozen or more performances of the operas given on the main stage, and several dozen related "fringe" events given in smaller venues.[117][134] The Festival records and offers videos of its most popular professional and amateur productions.[135] In connection with the 2009 festival, a contemporary critic wrote, "The appeal of G&S's special blend of charm, silliness and gentle satire seems immune to fashion."[6] There continue to be hundreds of amateur companies performing the Gilbert and Sullivan works worldwide.[136]

Recordings and broadcasts

editThe first commercial recordings of individual numbers from the Savoy operas began in 1898.[n 15] In 1917 the Gramophone Company (HMV) produced the first album of a complete Gilbert and Sullivan opera, The Mikado, followed by recordings of eight more.[138] Electrical recordings of most of the operas were then issued by HMV and Victor, beginning in the late 1920s, supervised by Rupert D'Oyly Carte.[139] The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company continued to produce well-regarded recordings until 1979, helping to keep the operas popular through the decades. Many of these recordings have been reissued on CD.[140] After the company was revived in 1988, it recorded seven of the operas.[127]

After the copyrights on the operas expired, numerous companies around the world released popular audio and video recordings of the operas.[127][141] In 1966 and again in the 1980s, BBC Radio presented complete cycles of the thirteen extant Gilbert and Sullivan operas, with dialogue.[142] Ad hoc casts of operatic singers conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent in the 1950s and 60s[143] and Sir Charles Mackerras in the 1990s[127] have made audio sets of several Savoy operas, and in the 1980s Alexander Faris conducted video recordings of eleven of the operas (omitting the last two) with casts including show-business stars as well as professional singers.[144] Joseph Papp's Broadway production of The Pirates of Penzance was put on record in 1981.[145][146] Since 1994, the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival has released numerous professional and amateur CDs and videos of its productions.[147] Ohio Light Opera has recorded several of the operas in the 21st century.[148] The Really Authentic Gilbert and Sullivan Performance Trust (RAGSPT) of Dunedin, New Zealand, recorded all 13 extant Savoy Operas between 2002 and 2012 and licensed the recordings on Creative Commons.[149]

Cultural influence

editFor nearly 150 years, Gilbert and Sullivan have pervasively influenced popular culture in the English-speaking world,[150] and lines and quotations from their operas have become part of the English language (even if not originated by Gilbert), such as "short, sharp shock", "What never? Well, hardly ever!", "let the punishment fit the crime", and "A policeman's lot is not a happy one".[16][151] The operas have influenced political style and discourse, literature, film and television, have been widely parodied by humorists, and have been quoted in legal rulings.[152]

The American and British musical owes a tremendous debt to G&S,[153][154] who were admired and copied by early musical theatre authors and composers such as Ivan Caryll, Adrian Ross, Lionel Monckton, P. G. Wodehouse,[155][156] Guy Bolton and Victor Herbert, and later Jerome Kern, Ira Gershwin, Yip Harburg,[157] Irving Berlin, Ivor Novello, Oscar Hammerstein II, and Andrew Lloyd Webber.[158] Gilbert's lyrics served as a model for such 20th-century Broadway lyricists as Cole Porter,[159] Ira Gershwin,[160] and Lorenz Hart.[7] Noël Coward wrote: "I was born into a generation that still took light music seriously. The lyrics and melodies of Gilbert and Sullivan were hummed and strummed into my consciousness at an early age. My father sang them, my mother played them, my nurse, Emma, breathed them through her teeth.... My aunts and uncles... sang them singly and in unison at the slightest provocation...."[161]

Professor Carolyn Williams has noted: "The influence of Gilbert and Sullivan – their wit and sense of irony, the send ups of politics and contemporary culture – goes beyond musical theater to comedy in general. Allusions to their work have made their way into our own popular culture".[162] Gilbert and Sullivan expert and enthusiast Ian Bradley agrees:

The musical is not, of course, the only cultural form to show the influence of G&S. Even more direct heirs are those witty and satirical songwriters found on both sides of the Atlantic in the twentieth century like Michael Flanders and Donald Swann in the United Kingdom and Tom Lehrer in the United States. The influence of Gilbert is discernible in a vein of British comedy that runs through John Betjeman's verse via Monty Python and Private Eye to... television series like Yes Minister... where the emphasis is on wit, irony, and poking fun at the establishment from within it in a way which manages to be both disrespectful of authority and yet cosily comfortable and urbane.[117]

The works of Gilbert and Sullivan are themselves frequently pastiched and parodied.[163][n 16] Well known examples of this include Tom Lehrer's The Elements and Clementine;[164] Allan Sherman's I'm Called Little Butterball, When I Was a Lad, You Need an Analyst and The Bronx Bird-Watcher;[165][166] and The Two Ronnies' 1973 Christmas Special.[167] Other comedians have used Gilbert and Sullivan songs as a key part of their routines, including Hinge and Bracket,[168] Anna Russell,[169] and the HMS Yakko episode of the animated TV series Animaniacs. Songs from Gilbert and Sullivan are often pastiched in advertising, and elaborate advertising parodies have been published, as have the likenesses of various Gilbert and Sullivan performers throughout the decades.[n 17] Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas are commonly referenced in literature, film and television in various ways that include extensive use of Sullivan's music or where action occurs during a performance of a Gilbert and Sullivan opera, such as in the film The Girl Said No.[170] There are also a number of Gilbert and Sullivan biographical films, such as Mike Leigh's Topsy-Turvy (2000) and The Story of Gilbert and Sullivan (1953), as well as shows about the partnership, including a 1938 Broadway show, Knights of Song[171] and a 1975 West End show called Tarantara! Tarantara![172][173]

It is not surprising, given the focus of Gilbert on politics, that politicians and political observers have often found inspiration in these works. Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist added gold stripes to his judicial robes after seeing them used by the Lord Chancellor in a production of Iolanthe.[174] Alternatively, Lord Chancellor Charles Falconer is recorded as objecting so strongly to Iolanthe's comic portrayal of Lord Chancellors that he supported moves to disband the office.[151] British politicians, beyond quoting some of the more famous lines, have delivered speeches in the form of Gilbert and Sullivan pastiches. These include Conservative Peter Lilley's speech mimicking the form of "I've got a little list" from The Mikado, listing those he was against, including "sponging socialists" and "young ladies who get pregnant just to jump the housing queue".[151]

Collaborations

editMajor works and original London runs

edit- Thespis; or, The Gods Grown Old (1871) 63 performances

- Trial by Jury (1875) 131 performances

- The Sorcerer (1877) 178 performances

- H.M.S. Pinafore; or, The Lass That Loved a Sailor (1878) 571 performances

- The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty (1879) 363 performances

- The Martyr of Antioch (cantata) (1880) (Gilbert helped to modify the poem by Henry Hart Milman)

- Patience; or Bunthorne's Bride (1881) 578 performances

- Iolanthe; or, The Peer and the Peri (1882) 398 performances

- Princess Ida; or, Castle Adamant (1884) 246 performances

- The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu (1885) 672 performances

- Ruddigore; or, The Witch's Curse (1887) 288 performances

- The Yeomen of the Guard; or, The Merryman and his Maid (1888) 423 performances

- The Gondoliers; or, The King of Barataria (1889) 554 performances

- Utopia, Limited; or, The Flowers of Progress (1893) 245 performances

- The Grand Duke; or, The Statutory Duel (1896) 123 performances

Parlour ballads

edit- "The Distant Shore" (1874)

- "The Love that Loves Me Not" (1875)

- "Sweethearts" (1875), based on Gilbert's 1874 play, Sweethearts

Overtures

editThe overtures from the Gilbert and Sullivan operas remain popular, and there are many recordings of them.[175] Most of them are structured as a potpourri of tunes from the operas. They are generally well-orchestrated, but not all of them were composed by Sullivan. However, even those delegated to his assistants were based on an outline he provided,[176] and in many cases incorporated his suggestions or corrections.[177] Sullivan invariably conducted them (as well as the entire operas) on opening night, and they were included in the published scores approved by Sullivan.[177]

Those Sullivan wrote himself include the overtures to Thespis, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, The Yeomen of the Guard, The Gondoliers and The Grand Duke. Sullivan's authorship of the overture to Utopia, Limited cannot be verified with certainty, as his autograph score is now lost, but it is likely attributable to him, as it consists of only a few bars of introduction, followed by a straight copy of music heard elsewhere in the opera (the Drawing Room scene). Thespis is now lost, but there is no doubt that Sullivan wrote its overture.[178] Very early performances of The Sorcerer used a section of Sullivan's incidental music to Shakespeare's Henry the VIII, as he did not have time to write a new overture, but this was replaced in 1884 by one executed by Hamilton Clarke.[179] Of those remaining, the overtures to H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance are by Alfred Cellier,[180] the overture to Patience is by Eugene d'Albert,[n 18] The overtures to The Mikado and Ruddigore are by Hamilton Clarke (although the Ruddigore overture was later replaced by one written by Geoffrey Toye).[183]

Most of the overtures are in three sections: a lively introduction, a slow middle section, and a concluding allegro in sonata form, with two subjects, a brief development, a recapitulation and a coda. Sullivan himself did not always follow this pattern. The overture to Princess Ida, for instance, has only an opening fast section and a concluding slow section. The overture to Utopia Limited is dominated by a slow section, with only a very brief original passage introducing it.[177]

In the 1920s, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company commissioned its musical director at the time, Geoffrey Toye, to write new overtures for Ruddigore and The Pirates of Penzance. Toye's Ruddigore overture entered the general repertory, and today is more often heard than the original overture by Clarke.[184] Toye's Pirates overture did not last long and is now presumed lost.[185] Sir Malcolm Sargent devised a new ending for the overture to The Gondoliers, adding the "cachucha" from the second act of the opera. This gave the Gondoliers overture the familiar fast-slow-fast pattern of most of the rest of the Savoy Opera overtures, and this version has competed for popularity with Sullivan's original version.[177][182]

Alternative versions

editTranslations

editGilbert and Sullivan operas have been translated into many languages, including Yiddish,[186] Hebrew, Portuguese, Swedish, Dutch, Danish, Estonian, Hungarian, Russian, Japanese, French, Italian, Spanish (reportedly including a zarzuela-style Pinafore), Catalan and others.[187]

There are many German versions of Gilbert and Sullivan operas, including the popular Der Mikado. There is even a German version of The Grand Duke. Some German translations of the operas were made by Friedrich Zell and Richard Genée, librettists of Die Fledermaus and other Viennese operettas, who even translated one of Sullivan's lesser-known operas, The Chieftain, as (Der Häuptling).[187]

Ballets

edit- Pineapple Poll, created by John Cranko in 1951 at Sadler's Wells Theatre; in repertoire at the Birmingham Royal Ballet. The ballet is based on Gilbert's 1870 Bab Ballad "The Bumboat Woman's Story", as is H.M.S. Pinafore. Cranko expanded the plotline of Gilbert's poem and added a happy ending. The music is arranged by Sir Charles Mackerras from themes by Sullivan.

- Pirates of Penzance - The Ballet!, created for the Queensland Ballet in 1991

Adaptations

editGilbert adapted the stories of H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado into children's books called The Pinafore Picture Book and The Story of The Mikado giving, in some cases, backstory that is not found in the librettos.[188][189][190] Many other children's books have since been written retelling the stories of the operas or adapting characters or events from them.[191] In the 19th century, the most popular Gilbert and Sullivan songs and music were adapted as dance pieces.[192]

Many musical theatre and film adaptations of the operas have been produced, including the following:

- The Swing Mikado (1938; Chicago – all-black cast)

- The Hot Mikado (1939) and Hot Mikado (1986)

- The Jazz Mikado (1927, Berlin)

- Hollywood Pinafore (1945)

- The Cool Mikado (1962 film)

- The Black Mikado (1975)

- Dick Deadeye, or Duty Done (1975 animated film)

- The Pirate Movie (1982 film)

- The Ratepayers' Iolanthe (1984; Olivier Award-winning musical) adapted by Ned Sherrin and Alistair Beaton[193]

- The Metropolitan Mikado (political satire adapted by Sherrin and Beaton, first performed at Queen Elizabeth Hall (1985) starring Louise Gold, Simon Butteriss, Rosemary Ashe, Robert Meadmore and Martin Smith)[194]

- Di Yam Gazlonim by Al Grand (1986; a Yiddish adaptation of Pirates; a New York production was nominated for a 2007 Drama Desk Award)[195]

- Pinafore! (A Saucy, Sexy, Ship-Shape New Musical) (adapted by Mark Savage, first performed at the Celebration Theater in Los Angeles, California in 2001; only one character is female, and all but one of the male characters are gay.[196]

- Gondoliers: A Mafia-themed adaptation of the opera, broadly rewritten by John Doyle and orchestrated and arranged Sarah Travis, was given at the Watermill Theatre and transferred to the Apollo Theatre in the West End in 2001. The production used Doyle's signature conceit of the actors playing their own orchestra instruments.[197]

- Parson's Pirates by Opera della Luna (2002)

- The Ghosts of Ruddigore by Opera della Luna (2003)

- Pinafore Swing, Watermill Theatre (2004: another Doyle adaptation in which the actors double as the orchestra)[198]

See also

editNotes, references and sources

editNotes

edit- ^ Sir George Grove wrote, "Form and symmetry he seems to possess by instinct; rhythm and melody clothe everything he touches; the music shows not only sympathetic genius, but sense, judgement, proportion, and a complete absence of pedantry and pretension; while the orchestration is distinguished by a happy and original beauty hardly surpassed by the greatest masters".[3]

- ^ "[Sullivan] will by unanimous consent be classed amongst the epoch-making composers, the select few whose genius and strength of will empowered them to find and found a national school of music, that is, to endow their countrymen with the undefinable, yet positive means of evoking in a man's soul, by the magic of sound, those delicate nuances of feeling which are characteristic of the emotional power of each different race".[4]

- ^ Jessie Bond created the mezzo-soprano roles in most of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas and is here leading into a description of Gilbert's role in reforming the Victorian theatre.[11]

- ^ Gilbert and Sullivan met at a rehearsal for a second run of Gilbert's Ages Ago at the Gallery of Illustration, probably in July 1870.[14]

- ^ At the beginning of the century there were only two main theatres in London;[26] by the late 1860s there were 32.[27]

- ^ Sullivan recalled Gilbert reading the libretto of Trial by Jury to him: "As soon as he had come to the last word he closed up the manuscript violently, apparently unconscious of the fact that he had achieved his purpose so far as I was concerned, in as much as I was screaming with laughter the whole time."[28]

- ^ Wachs argues that much of the material from a draft of this opera later made its way into Act II of The Pirates of Penzance.[32]

- ^ Gilbert was strongly influenced by the innovations in "stagecraft", now called stage direction, by the playwrights James Planché and especially Tom Robertson.[37]

- ^ The director Mike Leigh wrote in 2006, "That Gilbert was a good director is not in doubt. He was able to extract from his actors natural, clear performances, which served the Gilbertian requirements of outrageousness delivered straight."[39]

- ^ The run of H.M.S. Pinafore was exceeded by that of the West End production of the operetta Les cloches de Corneville, which opened earlier in the same year and was still running when H.M.S. Pinafore closed; Les cloches de Corneville held the record (705 performances) for London's longest musical theatre run until Dorothy (931 performances) surpassed it in 1886–1889.[42]

- ^ Gilbert eventually found another opportunity to present his "lozenge plot" in The Mountebanks, written with Alfred Cellier in 1892.[68]

- ^ A story circulated that Gilbert's inspiration for an opera set in Japan came when a Japanese sword mounted on his study wall fell down. The incident is portrayed in the film, but it is apocryphal.[69]

- ^ Gilbert's response to being told that the two spellings meant the same thing was: "Then I suppose you'll take it that if I say 'I admire your ruddy countenance', I mean 'I like your bloody cheek'."[77]

- ^ Although opera companies have rarely embraced Gilbert and Sullivan as part of the regular opera repertory, commentators have questioned the wisdom of this attitude.[131]

- ^ The first was "Take a pair of sparkling eyes", from The Gondoliers.[137]

- ^ Bradley (2005) devotes an entire chapter (chapter 8) to parodies and pastiches of G&S used in advertising, comedy and journalism.

- ^ For example, in 1961 Guinness published an entire book of parodies of Gilbert and Sullivan lyrics, illustrated with cartoons, to advertise Guinness stout. The book, by Anthony Groves-Raines with illustrations by Stanley Penn is called My Goodness! My Gilbert and Sullivan! Numerous examples of advertising uses of Gilbert and Sullivan and the best-known Gilbert and Sullivan performers (likenesses, often in costume, or endorsements) are described in Cannon, John. "Gilbert and Sullivan Celebrities in the World of Advertising", Gilbert & Sullivan News, pp. 10–14, Vol. IV, No. 13, Spring 2011.

- ^ The biographer Michael Ainger writes, "That evening (21 April 1881) Sullivan gave his sketch of the overture to Eugene d'Albert to score. D'Albert was a seventeen-year-old student at the National Training School (where Sullivan was the principal and supervisor of the composition dept.) and winner of the Mendelssohn Scholarship that year.[181] Several months before that, Sullivan had given d'Albert the task of preparing a piano reduction of The Martyr of Antioch for use in choral rehearsals of that 1880 work. The musicologist David Russell Hulme studied the handwriting in the score's manuscript and confirmed that it is that of Eugen, not of his father Charles (as had erroneously been reported by Jacobs), both of whose script he sampled and compared to the Patience manuscript.[182]

References

edit- ^ Davis, Peter G. Smooth Sailing, New York magazine, 21 January 2002, accessed 6 November 2007

- ^ a b Leigh, Mike. "True anarchists", The Guardian, 4 November 2007, accessed 6 November 2007

- ^ "Arthur Sullivan 1842–1900, The Musical Times, vol. 41, no. 694, 1 December 1900, pp. 785–787

- ^ Mazzucato Gian Andrea. "Sir Arthur Sullivan: The National Composer", Musical Standard, vol. 12, no. 311, 30 December 1899, pp. 385–386

- ^ Bradley (2005), Chapter 1

- ^ a b c Hewett, Ivan. "The Magic of Gilbert and Sullivan". The Telegraph, 2 August 2009, accessed 14 April 2010.

- ^ a b [Downs, Peter. "Actors Cast Away Cares", Hartford Courant, 18 October 2006

- ^ a b Crowther, Andrew. The Life of W. S. Gilbert, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012.

- ^ Stedman, pp. 26–29, 123–24, and the introduction to Gilbert's Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales

- ^ Bond, Jessie. The Reminiscences of Jessie Bond: Introduction, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 May 2007.

- ^ Bond, Introduction

- ^ Stedman, pp. 62–68; Bond, Jessie, The Reminiscences of Jessie Bond: Introduction, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. Ages Ago – Early Days, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ Crowther (2011), p. 84

- ^ Stedman, pp. 77–90

- ^ a b "An Illustrated Interview with Sir Arthur Sullivan, by Arthur H Lawrence, Part 1", The Strand Magazine, Volume xiv, No.84 (December 1897). See also Sullivan's Letter to The Times, 27 October 1881, Issue 30336, pg. 8 col C

- ^ Shepherd, Marc, Discography of Sir Arthur Sullivan: Orchestral and Band Music, The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, accessed 10 June 2007

- ^ Stephen Turnbull's Biography of Arthur Sullivan, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 22 November 2006

- ^ Harris, pp. X–XI

- ^ Ainger, p. 72

- ^ a b Tillett, Selwyn and Spencer, Roderic. "Forty Years of Thespis Scholarship", accessed 20 July 2021

- ^ Walters, Michael. "Thespis: a reply", W. S. Gilbert Society Journal, Vol. 4, part 3, Issue 29. Summer 2011.

- ^ Williams, p. 35

- ^ Richards, p. 9

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 2–3

- ^ Bratton, Jacky, "Theatre in the 19th century" Archived 10 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, British Library, 2014

- ^ "The Theatres of London", Watson's Art Journal, 22 February 1868, p. 245

- ^ Lawrence, p. 105

- ^ Walbrook, H. M. (1922), Gilbert and Sullivan Opera, a History and Comment (Chapter 3), The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 May 2007

- ^ Ayer p. 408

- ^ Bradley (1996), p. 14

- ^ Wachs, Kevin. "Let’s vary piracee / With a little burglaree!", The Gasbag, Issue 227, Winter 2005, accessed 8 May 2012.

- ^ Ainger, p. 130

- ^ The Sorcerer, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 May 2007

- ^ Stedman, p. 155

- ^ Bradley (1996), p. 178; and Bowyer, Bertram (Lord Denham). "D'Oyly Carte Opera Company", UK Parliament, 1 April 1998 (quote: "...the 'Gilbertian ending' ... after two acts in which the principal protagonists contrive to get themselves into a more and more convoluted state of utter hopelessness, a final twist – whimsical but wholly logical and even believable – makes everything come out all right again, and everyone lives happily ever after."

- ^ A Stage Play; and Bond, Jessie, Introduction.

- ^ a b Cox-Ife, p. 27

- ^ Leigh, Mike. "True anarchists", [1], The Guardian, 4 November 2006

- ^ Bond, Jessie. The Reminiscences of Jessie Bond, Chapter 4 (1930), reprinted at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 15 November 2008, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 6

- ^ Traubner, p. 183; and Herbert, pp. 1598–1599, 1605 and 1907

- ^ a b Rosen, Zvi S. The Twilight of the Opera Pirates: A Prehistory of the Right of Public Performance for Musical Compositions. Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, Vol. 24, 2007, accessed 21 May 2007. See also Prestige, Colin. "D'Oyly Carte and the Pirates", a paper presented at the International Conference of G&S held at the University of Kansas, May 1970

- ^ Stedman, pp. 170–171

- ^ Rollins and Witts, pp. 7–15

- ^ a b Traubner, p. 176

- ^ Bradley (1999), p. 261

- ^ Samuels, Edward. "International Copyright Relations" Archived 28 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine in The Illustrated Story of Copyright, Edwardsamuels.com, accessed 19 September 2011. Note the box "When Gilbert and Sullivan attacked the 'Pirates.'"

- ^ Perry, Helga. "Transcription of an opening night review in New York", Savoyoperas.org.uk, 27 November 2000, accessed 27 May 2009

- ^ In one unsuccessful attempt, the partners hired an American, George Lowell Tracy, to create the piano arrangement of the scores of Princess Ida and The Mikado, hoping that he would obtain rights that he could assign to them. See, Murrell, Pam. "Gilbert & Sullivan’s American Ally", In the Muse, US Library of Congress, 5 August 2020.

- ^ Rich, Frank. "Stage: Pirates of Penzance on Broadway". The New York Times, 9 January 1981, accessed 2 July 2010

- ^ Theatre Record, 19 May 1982 to 2 June 1982, p. 278

- ^ Stone, David. Robert Cunningham (1892–93), Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, 4 September 2009, accessed 25 May 2017

- ^ Ellmann, pp. 135 and 151–152

- ^ Bradley (1996), p. 269

- ^ "Savoy Theatre", arthurlloyd.co.uk, accessed 20 July 2007; and Burgess, Michael. "Richard D'Oyly Carte", The Savoyard, January 1975, pp. 7–11

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 8

- ^ Quoted in Allen 1975b, p. 176

- ^ Beatty-Kingston, William, "Our Musical Box", The Theatre, 1 January 1883, p. 27

- ^ Cole, Sarah. Broken Hearts, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 23 December 2000, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ "W. S. Gilbert", The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21), Volume XIII, "The Victorian Age", Part One. VIII. Nineteenth-Century Drama, § 15, Bartleby.com, accessed 27 May 2009

- ^ Bradley (1996), p. 176

- ^ Baily, p. 250

- ^ a b c d e f g h Crowther, Andrew (13 August 2018). "The Carpet Quarrel Explained". The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Stedman, pp. 200–201

- ^ Jacobs, p. 187

- ^ Ainger, p. 236

- ^ Stedman, p. 284

- ^ Jones, Brian. "The sword that never fell", W. S. Gilbert Society Journal 1 (1), Spring 1985, pp. 22–25

- ^ "Workers and Their Work: Mr. W.S. Gilbert", Daily News, 21 January 1885, reprinted at the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ Review of The Mikado Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Pamphletpress.org, accessed 27 May 2009

- ^ Dark and Grey, p. 101

- ^ Bradley (1996), pp. 878, 975 and 1087

- ^ Wilson and Lloyd, p. 37

- ^ Kenrick, John. "The Gilbert & Sullivan Story: Part III, Musicals 101, 2000, accessed 20 July 2021

- ^ See the Pall Mall Gazette's satire of Ruddygore.

- ^ Bradley (1996), p. 656

- ^ "Ruddigore", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 20 July 2021

- ^ Information from the book Tit-Willow or Notes and Jottings on Gilbert and Sullivan Operas by Guy H. and Claude A. Walmisley (Privately Printed, Undated, early 20th century)

- ^ Perry, Helga. Ruddygore, Illustrated London News, 9 January 1887, Savoyoperas.org.uk, accessed 27 May 2009

- ^ Critical apparatus in Hulme, David Russell, ed., Ruddigore. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2000)

- ^ Williams, pp. 282–284

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. "Ages Ago – Early Days"; and "St George's Hall", The Times, 27 December 1881, via The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 3 April 2018

- ^ Ainger, pp. 265 and 267

- ^ Ainger, pp. 265 – 276

- ^ "Savoy Theatre", The Times, 4 October 1888, p. 11

- ^ Quoted in Allen 1975, p. 312

- ^ Jacobs, p. 283

- ^ Jacobs, p. 288

- ^ The Gondoliers at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 July 2007

- ^ a b Baily, p. 344

- ^ Ainger, p. 303

- ^ See, e.g., Stedman, pp. 254–56 and 323–24 and Ainger, pp. 193–94.

- ^ See, e.g. Ainger, p. 288, or Wolfson, p. 3

- ^ See, e.g. Jacobs, p. 73; Crowther, Andrew, The Life of W.S. Gilbert, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012; and Bond, Jessie. The Reminiscences of Jessie Bond: Chapter 16, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ a b c d Ford, Tom. "G&S: the Lennon/McCartney of the 19th century" Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Limelight Magazine, Haymarket Media Ltd., 8 June 2011

- ^ Stedman, p. 270

- ^ a b "Why did Gilbert and Sullivan quarrel over a carpet?", Classical Music, 26 August 2020

- ^ Ainger, pp. 312–316

- ^ a b Shepherd, Marc. "Introduction: Historical Context", The Grand Duke, p. vii, New York: Oakapple Press, 2009. Linked at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 7 July 2009.

- ^ Gilbert's Plays, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ Wolfson, p. 7

- ^ Wolfson, passim

- ^ Wolfson, pp. 61–65

- ^ Ainger, pp. 355–358

- ^ Howarth, Paul. "The Sorcerer 21st Anniversary Souvenir", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 8 October 2009, accessed 21 August 2012

- ^ a b Walbrook, H. M. "The English Offenbach", Gilbert & Sullivan Opera: A History and a Comment, reprinted at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 28 September 2003, accessed 27 May 2009

- ^ Joseph, p. 146

- ^ Wilson and Lloyd, p. 83

- ^ Baily, p. 425

- ^ Rollins and Witts, passim

- ^ Joseph, passim

- ^ Jellinek, Hedy and George. "The One World of Gilbert and Sullivan", Saturday Review, 26 October 1968, pp. 69–72 and 94

- ^ Wood, Henry. Foreword in Walbrook

- ^ Chesterton, p. xv

- ^ "The Lasting Charm of Gilbert and Sullivan: Operas of an Artificial World", The Times, 14 February 1957, p. 5

- ^ a b c Bradley, Ian. Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan (2005)

- ^ Cellier and Bridgeman, p. 393

- ^ Cellier and Bridgeman, p. 394

- ^ Cellier and Bridgeman, pp. 394–96

- ^ Cellier and Bridgeman, pp. 398–99

- ^ Fletcher, Juliet. "Yeomen of the Guard: The Savoy Company celebrates 100 years of taking on Gilbert and Sullivan" Archived 1 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, CityPaper, September 2001, accessed 25 February 2012

- ^ The Savoy Company official website, accessed 25 February 2012

- ^ "The Land of Gilbert and Sullivan", Life, 11 October 1948, vol. 25, pp. 86–87