Gliese 581g /ˈɡliːzə/ was a candidate exoplanet postulated to orbit within the Gliese 581 system, twenty light-years from Earth.[9] It was discovered by the Lick–Carnegie Exoplanet Survey, and was the sixth planet claimed to orbit the star;[10] however, its existence could not be confirmed by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) / High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) survey team, and was ultimately refuted.[9][11][12] It was thought to be near the middle of the habitable zone of its star,[13] meaning it could sustain liquid water—a necessity for all known life—on its surface, if there are favorable atmospheric conditions on the planet.

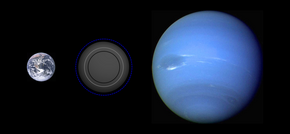

Size comparison of Gliese 581g with Earth and Neptune (Based on selected hypothetical modeled compositions) | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Steven S. Vogt et al.[1] |

| Discovery site | Keck Observatory, Hawaii[2][3][4] |

| Discovery date | September 29, 2010[1][5] |

| Radial velocity[1] | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Epoch JD 2451409.762[1] | |

| 0.13 AU (19,000,000 km)[6] | |

| Eccentricity | 0[1] |

| 32[6] d | |

| 271 ± 48[1] | |

| Semi-amplitude | 1.29 ± 0.19[1] |

| Star | Gliese 581[1][7] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Temperature | 242 K (−31 °C; −24 °F) to 261 K (−12 °C; 10 °F)[8] |

Gliese 581g was claimed to be detected by astronomers of the Lick–Carnegie Exoplanet Survey. The authors stated that data sets from both the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) and HARPS were needed to sense the planet; however, the ESO/HARPS survey team could not confirm its existence. The planet remained unconfirmed as consensus for its existence could not be reached. Additional reanalysis only found evidence for four planets, but the discoverer, Steven S. Vogt, did not agree with those conclusions. In 2012, a reanalysis by Vogt supported its existence.[14] A new study in 2014 concluded that it was a false positive,[15][9] a conclusion which has been further confirmed by subsequent studies.[12] The planet was thought to be tidally locked to its star. If the planet has a dense atmosphere, it may be able to circulate heat. The actual habitability of the planet depends on the composition of its surface and the atmosphere. It was thought to have temperatures around −37 to −11 °C (−35 to 12 °F). By comparison, Earth has an average surface temperature of 15 °C (59 °F)—while Mars has an average surface temperature of about −63 °C (−81 °F). The planet was said by Vogt to have a "100%" chance of supporting life.[16] The supposed detection of Gliese 581g was said to foreshadow what Vogt called "a second Age of Discovery".[1]

History

edit

Discovery

editThe planet's discovery was claimed in September 2010,[13] to have been detected by astronomers in the Lick–Carnegie Exoplanet Survey, led by principal investigator Steven Vogt,[13] professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California, Santa Cruz,[13] and co-investigator R. Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. The discovery was made using radial velocity measurements,[13][1] combining 122 observations obtained over 11[13] years from the HIRES instrument of the W. M. Keck Observatory[13] with 119 measurements obtained over 4.3 years from the HARPS[13] instrument of the ESO 3.6 m Telescope[13] at La Silla Observatory.[4] In addition, brightness measurements of the star were confirmed with a robotic telescope[13] from Tennessee State University.[1]

After subtracting the signals of the previously known Gliese 581 planets, b, c, d and e, the signals of two[13] additional planets were apparent: a 445-day signal from a newly recognized outermost planet designated f, and the 37-day signal from Gliese 581g.[1][17] The probability that the detection of the latter was spurious was estimated at only 2.7 in a million.[1] The authors stated that while the 37-day signal is "clearly visible in the HIRES data set alone", "the HARPS data set alone is not able to reliably sense this planet" and concluded, "It is really necessary to combine both data sets to sense all these planets reliably".[1] The Lick–Carnegie team explained the results of their research in a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal, which were also made available in preprint[18] version on arXiv.[13] Although not sanctioned by the IAU's naming conventions, Vogt's team informally referred to the planet as "Zarmina's World" after his wife,[19] and in some cases simply as Zarmina.

During a press release announcing the discovery, Vogt et al. acknowledged that the "Gliese 581 system has a somewhat checkered history of habitable planet claims," as two previously discovered planets in the same system, Gliese 581c and d, were also regarded as potentially habitable, but later evaluated as being outside the conservatively defined habitable zone.[13]

Nondetection in new HARPS data analysis

editTwo weeks after the announcement of the discovery of Gliese 581g, another team—led by Michael Mayor of the Geneva Observatory[13]—reported that in a new analysis of 179 measurements taken by the HARPS[13] spectrograph over 6.5 years, neither planet g[13] nor planet f was detectable.[20][21][22] An astronomer who works on HARPS data at the Geneva Observatory, Francesco Pepe, said in an email for an Astrobiology Magazine article republished on Space.com, "The reason for that is that, despite the extreme accuracy of the instrument and the many data points, the signal amplitude of this potential fifth planet is very low and basically at the level of the measurement noise".[13][23] The Geneva team had also published their paper on arXiv,[13] but it appeared to not[13] have been accepted for publication[why?].

Vogt responded to the latest concerns by saying, "I am not overly surprised by this as these are very weak signals, and adding 60 points onto 119 does not necessarily translate to big gains in sensitivity."[24] More recently, Vogt added, "I feel confident that we have accurately and honestly reported our uncertainties and done a thorough and responsible job extracting what information this data set has to offer. I feel confident that anyone independently analyzing this data set will come to the same conclusions."[25]

Differences in the two groups' results may involve the planetary orbital characteristics assumed in calculations. According to Massachusetts Institute of Technology astronomer Sara Seager, Vogt postulated the planets around Gliese 581 had perfectly circular orbits whereas the Swiss group thought the orbits were more eccentric.[26] This difference in approach may be the reason for the disagreement, according to Alan Boss.[26] Butler remarked that with additional observations, "I would expect that on the time scale of a year or two this should be settled."[20] Other astronomers also supported a deliberate evaluation: Seager stated, "We will have consensus at some point; I don't think we need to vote right now." Ray Jayawardhana noted, "Given the extremely interesting implications of such a discovery, it's important to have independent confirmation."[26] Gliese 581g is listed as "retracted" in the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.[27]

Further analyses of HIRES/HARPS data

editIn December 2010, a claimed methodological error was reported—by a group led by Rene Andrae of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy—in the data analysis that led to the discovery of Gliese 581f and g.[28][13]

In 2011, another reanalysis—performed by a group led by Philip Gregory of the University of British Columbia—found no clear evidence for a fifth planetary signal in the combined HIRES/HARPS data set.[13][29] The claim was made that the HARPS data provided only some evidence for 5 planet signals, while incorporation of both data sets actually degraded the evidence for more than four planets (i.e., none for 581f or 581g).[29] Mikko Tuomi of the University of Hertfordshire performed a Bayesian reanalysis of the HARPS and HIRES data with the result that they "do not imply the conclusion that there are two additional companions orbiting GJ 581".[30]

"I have studied [the paper] in detail and do not agree with his conclusions,"[31] Steven Vogt said in reply, concerned that Gregory has considered the HIRES data as more uncertain.[32] "The question of Gliese 581g's existence won't be settled definitively until researchers gather more high-precision radial velocity data", Vogt said. However, Vogt expects further analysis to strengthen the case for the planet.[33]

By performing a number of statistical tests, Guillem Anglada-Escudé of the Carnegie Institute of Washington concluded that the existence of Gl 581g was well supported by the available data, despite the presence of a statistical degeneracy that derives from an alias of the first eccentric harmonic of another planet in the system.[34] In a preprint posted to arXiv, Anglada-Escudé and Rebekah Dawson claimed that, "with the data we have, the most likely explanation is that this planet is still there."[34][35]

2012 reanalysis of HARPS data

editIn July 2012, Vogt reanalyzed the 2011 data proposed by Forveille[who?] et al., noting that there were five objects (Gliese 581b, e, c, g, d, with no evidence for f). Planet g was orbiting around 0.13 AU with an orbital period of thirty-two days, placing it inside the habitable zone. Vogt concluded that the object had a minimum mass of 2.2 M and had a false positive probability of less than 4%. Vogt also said that they couldn't come to same conclusion as the Geneva team, without removing data points, "I don't know whether this omission was intentional or a mistake," he said, "I can only say that, if it was a mistake, they've been making that same mistake more than once now, not only in this paper, but in other papers as well."[13] Vogt then said that the planet was there as long as all of the planets had circular orbits, and that the circular orbits work because “of dynamic stability, goodness-of-fit, and principle of parsimony (Occam's Razor)."[13][3][6]

Further studies and refutation

editTwo studies in 2013 did not find evidence of Gliese 581g, only finding evidence for four—or three—planets in the system.[36][37]

A study in 2014—published in Science—[38] led by postdoctoral[38] researcher Paul Robertson concluded that Gliese 581d is "an artifact of stellar activity which, when incompletely corrected, causes the false detection of planet g."[9][7][38] "They were very high value targets if they were real," Robertson said, "But unfortunately we found out that they weren't."[38] It was pointed out—during a press release by Penn State University—that sunspots could sometimes masquerade as planetary signals.[13] An additional study concluded that Gliese 581g's existence depends on Gliese 581d's eccentricity.[9] The planet was later delisted from the Habitable Exoplanets Catalog, which is run by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo.[13] Later, in October that year, Abel Mendez wrote—in a blog post characterizing "false starts" in exoplanet habitability—[13][39] that the planet does not exist.

In 2015, a pair of researchers led by Guillem Anglada-Escudé of the University of London questioned the methodology of the 2014 study and suggested planet Gliese 581d really could exist, despite stellar variability, and the 2014 refutation of the existence of Gliese 581d and g was triggered by poor and inadequate analysis of the data, saying that the statistical method used by Robertson's team was "simply inadequate for identifying small planets like Gliese 581d", urging that the data be reanalyzed using a "more accurate model."[40][13][41] However, this response did not make any claim for the existence of Gliese 581g, and was published along with a rebuttal by the team that published the 2014 refutation.[42] Most further studies have confirmed the stellar, rather than planetary, origin of the signal corresponding to Gliese 581d, and consequently Gliese 581g,[43][44][11] with one such study explicitly refuting g.[12]

Physical characteristics

edit

Tidal locking

editBecause of Gliese 581g's proximity to its parent star, it is predicted to be tidally locked to Gliese 581. Just as Earth's Moon always presents the same face to the Earth, the length of Gliese 581g's sidereal day would then precisely match the length of its year, meaning it would be permanently light[13] on one half and permanently dark[13] on the other half of its surface.[1][45]

Atmosphere

editAn atmosphere that is dense will circulate heat, potentially allowing a wide area on the surface to be habitable.[46] For example, Venus has a solar rotation rate approximately 117 times slower than Earth's, producing prolonged days and nights. Despite the uneven distribution of sunlight over time intervals shorter than several months, unilluminated areas of Venus are kept almost as hot as the day side by globally circulating winds.[47] Simulations have shown that an atmosphere containing appropriate levels of CO2 and H2O need only be a tenth the pressure of Earth's atmosphere (100 mbar) to effectively distribute heat to the night side.[48] Current technology cannot determine the atmospheric or surface composition of the planet due to the overpowering light of its parent star.[49]

Whether or not a tidally locked planet with the orbital characteristics of Gliese 581g is actually habitable depends on the composition of the atmosphere and the nature of the planetary surface. A comprehensive modeling study[50] including atmospheric dynamics, realistic radiative transfer and the physics of formation of sea ice (if the planet has an ocean) indicates that the planet can become as hot as Venus if it is dry and allows carbon dioxide to accumulate in its atmosphere. The same study identified two habitable states for a water-rich planet. If the planet has a very thin atmosphere, a thick ice crust forms over most of the surface, but the substellar point remains hot enough to yield a region of thin ice or even episodically open water. If the planet has an atmosphere with Earthlike pressures, containing approximately 20% (molar) carbon dioxide, then the greenhouse effect is sufficiently strong to maintain a pool of open water under the substellar point with temperatures comparable to the Earth's tropics. This state has been dubbed "Eyeball Earth" by the author.[50] Modeling of the effect of tidal locking on Gliese 581g's possible atmosphere, using a general circulation model employing an atmosphere with Earthlike surface pressure but a highly idealized representation of radiative processes, indicates that for a solid-surface planet the locations of maximum warmth would be distributed in a sideways chevron-shaped pattern centered near the substellar point.[51][52]

Climate

editIt is estimated that the average global equilibrium temperature (the temperature in the absence of atmospheric effects) of Gliese 581g would range from 209 to 228 K (−64 to −45 °C, or −84 to −49 °F) for Bond albedos (reflectivities) from 0.5 to 0.3 (with the latter being more characteristic of the inner Solar System). Adding an Earthlike greenhouse effect would yield an average surface temperature in the range of 236 to 261 K (−37 to −12 °C, or −35 to 10 °F).[1][8] Gliese 581g would be in an orbit where a silicate weathering thermostat could operate, and this could lead to accumulation of sufficient carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to permit liquid water to exist at the surface, provided the planet's composition and tectonic behavior could support sustained outgassing.[50]

| Temperature comparisons |

Mercury | Venus | Earth | Gliese 581g | Mars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global equilibrium temperature |

431 K 158 °C 316 °F |

307 K 34 °C 93 °F |

255 K −18 °C −0.4 °F |

209 K to 228 K −64 °C to −45 °C −83 °F to −49 °F |

206 K −67 °C −88.6 °F |

| Adjusted for | — | 737 K 464 °C 867 °F |

288 K 15 °C 59 °F |

236 K to 261 K −37 °C to −12 °C −35 °F to 10 °F Assumes Earth atmosphere |

210 K −63 °C −81 °F |

| Tidally locked |

3:2 | Almost | No | Likely | No |

| Global Bond albedo |

0.142 | 0.9 | 0.29 | 0.5 to 0.3 | 0.25 |

| Refs.[1][8][53][54][55][56] | |||||

By comparison, Earth's present global equilibrium temperature is 255 K (−18 °C), which is raised to 288 K (15 °C) by greenhouse effects. However, when life evolved early in Earth's history, the Sun's energy output is thought to have been only about 75% of its current value,[57] which would have correspondingly lowered Earth's equilibrium temperature under the same albedo conditions. Yet Earth maintained equable temperatures in that era, perhaps with a more intense greenhouse effect,[58] or a lower albedo,[59] than at present.

Current Martian surface temperatures vary from lows of about −87 °C (−125 °F) during polar winter to highs of up to −5 °C (23 °F) in summer.[53] The wide range is due to the rarefied atmosphere, which cannot store much solar heat, and the low thermal inertia of the soil.[60] Early in its history, a denser atmosphere may have permitted the formation of an ocean on Mars.[61]

Habitability

editThe planet is thought to be located within the habitable zone of its parent star, a red dwarf, which is cooler than the Sun. That means planets need to orbit closer to the star than in the Solar System to maintain liquid water on their surface. While habitability is generally defined by the planets ability to support liquid water, there are many factors that can influence it. This includes the atmosphere of the planet and the variability of its parent star in terms of emitting energy.[13]

In an interview with Lisa-Joy Zgorski of the National Science Foundation, Steven Vogt was asked what he thought about the chances of life existing on Gliese 581g. Vogt was optimistic:

I'm not a biologist, nor do I want to play one on TV. Personally, given the ubiquity and propensity of life to flourish wherever it can, I would say that... the chances of life on this planet are 100%. I have almost no doubt about it."[16] In the same article Dr. Seager is quoted as saying "Everyone is so primed to say here's the next place we're going to find life, but this isn't a good planet for follow-up.[16]

According to Vogt, the long lifetime of red dwarfs improves the chances of life being present. "It's pretty hard to stop life once you give it the right conditions", he said.[62] According to the Associated Press interview with Steven Vogt:

Life on other planets doesn't mean E.T. Even a simple single-cell bacteria or the equivalent of shower mold would shake perceptions about the uniqueness of life on Earth.[62]

Implications

editScientists have monitored only a relatively small number of stars in the search for exoplanets. The discovery of a potentially habitable planet like Gliese 581g so early in the search might mean that habitable planets are more widely distributed than had been previously believed.[63] According to Vogt, the discovery "implies an interesting lower limit on η⊕ as there are only ~116 known solar-type or later stars ... out to the 6.3 parsec distance of GJ 581" (η⊕, "eta-Earth", refers to the fraction of stars with potentially habitable planets).[1] This finding foreshadows what Vogt calls a new, second Age of Discovery in exoplanetology:

Confirmation by other teams through additional high-precision RVs would be most welcome. But if GJ 581g is confirmed by further RV scrutiny, the mere fact that a habitable planet has been detected this soon, around such a nearby star, suggests that η⊕ could well be on the order of a few tens of percent, and thus that either we have just been incredibly lucky in this early detection, or we are truly on the threshold of a second Age of Discovery.[1]

If the fraction of stars with potentially habitable planets (η⊕, "eta-Earth") is on the order of a few tens of percent as Vogt proposes, and the Sun's stellar neighborhood is a typical sample of the galaxy, then the discovery of Gliese 581g in the habitable zone of its star points to the potential of billions of Earthlike planets in our Milky Way galaxy alone.[45]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Vogt, Steven S.; Butler, R. Paul; Rivera, Eugenio J.; Haghighipour, Nader; Henry, Gregory W.; Williamson, Michael H. (September 29, 2010). "The Lick-Carnegie Exoplanet Survey: A 3.1 M_Earth Planet in the Habitable Zone of the Nearby M3V Star Gliese 581". The Astrophysical Journal. 723 (1): 954–965. arXiv:1009.5733. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..954V. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/954. S2CID 3163906.

- ^ Smith, Yvette (September 29, 2010). "NASA and NSF-Funded Research Finds First Potentially Habitable Exoplanet". NASA. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (August 20, 2012). "Just Right, or Nonexistent? Dispute Over 'Goldilocks' Planet Gliese 581G". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Alleyne, Richard (September 29, 2010). "Gliese 581g the most Earth like planet yet discovered". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on October 2, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Sanders, Laura. "A little wobble spurs hope for finding life on distant worlds: extrasolar planet is in the right location to be habitable". Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c Vogt, Steven S.; Butler, R. Paul; Haghighipour, Nader (July 18, 2012). "GJ 581 update: Additional Evidence for a Super-Earth in the Habitable Zone". Astronomische Nachrichten. 333 (7): 561–575. arXiv:1207.4515. Bibcode:2012AN....333..561V. doi:10.1002/asna.201211707. S2CID 13901846.

- ^ a b Quenqua, Douglas (July 7, 2014). "Earthlike Planets May Be Merely an Illusion". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c Stephens, Tim (September 29, 2010). "Newly discovered planet may be first truly habitable exoplanet". University News & Events. University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Robertson, Paul; Mahadevan, Suvrath; Endl, Michael; Roy, Arpita (July 25, 2014). "Stellar activity masquerading as planets in the habitable zone of the M dwarf Gliese 581". Science. 345 (6195): 440–444. arXiv:1407.1049. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..440R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.767.2071. doi:10.1126/science.1253253. PMID 24993348. S2CID 206556796.

- ^ Hsu, Jeremy (October 2010). "A Million Questions About Habitable Planet Gliese 581g (Okay, 12)". Space.com. Purch Group. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Trifonov, T.; Kürster, M.; et al. (February 2018). "The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs. First visual-channel radial-velocity measurements and orbital parameter updates of seven M-dwarf planetary systems". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 609: A117. arXiv:1710.01595. Bibcode:2018A&A...609A.117T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201731442.

- ^ a b c Dodson-Robinson, Sarah E.; Delgado, Victor Ramirez; Harrell, Justin; Haley, Charlotte L. (2022-04-01). "Magnitude-squared Coherence: A Powerful Tool for Disentangling Doppler Planet Discoveries from Stellar Activity". The Astronomical Journal. 163 (4): 169. arXiv:2201.13342. Bibcode:2022AJ....163..169D. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac52ed. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 246430514.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Howell, Elizabeth (May 4, 2016). "Gliese 581g: Potentially Habitable Planet — If It Exists". Space.com. Purch Group. Archived from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Wall, Mike (23 July 2012). "Is Planet Gliese 581g Really the 'First Potentially Habitable' Alien World?". Space.com. Purch Group. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Grant, Andrew. "Habitable planets' reality questioned: star's magnetic activity could have led to false detections". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c NSF. Press Release 10-172 - Video Archived 2021-02-11 at the Wayback Machine. Event occurs at 41:25-42:31. See Overbye, Dennis (September 29, 2010). "New Planet May Be Able to Nurture Organisms". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Alexander, Amir. "Billions and Billions? Discovery of Habitable Planet Suggests Many More are Out There". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 2010-10-09. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ^ Vogt, Steven (2010). "The Lick-Carnegie Exoplanet Survey: A 3.1 M☉ Planet in the Habitable Zone of the Nearby M3V Star Gliese 581". The Astrophysical Journal. 723 (1): 954–965. arXiv:1009.5733. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..954V. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/954. S2CID 3163906.

- ^ Meichsner, Von Irene (September 30, 2010). "Erdähnlicher Planet entdeckt" [Terrestrial Planet discovered]. Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger (in German). Archived from the original on October 2, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Kerr, Richard A. (October 12, 2010). "Recently Discovered Habitable World May Not Exist". Science Now. AAAS. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Forveille, Thierry; Bonfils, Xavier; Delfosse, Xavier; Alonso, Roi; Udry, Stéphane; Bouchy, François; Gillon, Michaël; Lovis, Christophe; Neves, Vasco; Mayor, Michel; Pepe, Francesco; Queloz, Didier; Santos, Nuno C.; Ségransan, Damien; Almenara, José M.; Deeg, Hans-Jörg; Rabus, Markus (September 12, 2011). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XXXII. Only 4 planets in the Gl~581 system". arXiv:1109.2505 [astro-ph.EP].

...Our dataset therefore has strong diagnostic power for planets with the parameters of Gl 581f and Gl 581g, and we conclude that the Gl 581 system is unlikely to contain planets with those characteristics...

- ^ Bonfils, Xavier; Delfosse, Xavier; Udry, Stéphane; Forveille, Thierry; Mayor, Michel; Perrier, Christian; Bouchy, François; Gillon, Michaël; Lovis, Christophe; Pepe, Francesco; Queloz, Didier; Santos, Nuno C.; Ségransan, Damien; Bertaux, Jean-Loup (2011). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XXXI. The M-dwarf sample". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 549: A109. arXiv:1111.5019. Bibcode:2013A&A...549A.109B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014704. S2CID 119288366.

- ^ Mullen, Leslie (October 12, 2010). "Doubt Cast on Existence of Habitable Alien World". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 2018-01-25. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Grossman, Lisa (October 12, 2010). "Exoplanet Wars: "First Habitable World" May Not Exist". Wired. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Wall, Mike (October 13, 2010). "Astronomer Stands By Discovery of Alien Planet Gliese 581g Amid Doubts". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Cowen, Ron (October 13, 2010). "Swiss team fails to confirm recent discovery of an extrasolar planet that might have right conditions for life". Science News. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2010.

- ^ "GJ 581 g". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. 1995. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

Planet Status: Retracted

- ^ Rene Andrae; Tim Schulze-Hartung; Peter Melchior (2010). "Dos and don'ts of reduced chi-squared". arXiv:1012.3754 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ a b Gregory (2011). "Bayesian Re-analysis of the Gliese 581 Exoplanet System". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 415 (3): 2523–2545. arXiv:1101.0800. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415.2523G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18877.x. S2CID 38331034.

- ^ Mikko Tuomi (2011). "Bayesian re-analysis of the radial velocities of Gliese 581. Evidence in favour of only four planetary companions". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 528: L5. arXiv:1102.3314. Bibcode:2011A&A...528L...5T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015995. S2CID 11439465.

- ^ "Habitable planet find doubted by B.C. scientist". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. January 14, 2011. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ Wall, Mike (February 19, 2011). "R.I.P. Possibly Habitable Planet Gliese 581g? Not So Fast, Co-Discoverer Says". Space.com. Purch Group. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ Yudhijt Bhattacharjee (July 27, 2012). "Data Dispute Revives Exoplanet Claim". Science. 337 (6093): 398. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..398B. doi:10.1126/science.337.6093.398. PMID 22837499.

- ^ a b Guillem Anglada-Escudé (2010). "Aliases of the first eccentric harmonic : Is GJ 581g a genuine planet candidate?". arXiv:1011.0186 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (January 18, 2011). "New Study Finds No Sign of 'First Habitable Exoplanet'". Wired. Archived from the original on May 21, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Roman Baluev (2013). "The impact of red noise in radial velocity planet searches: Only three planets orbiting GJ581?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 429 (3): 2052–2068. arXiv:1209.3154. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.429.2052B. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts476.

- ^ Hatzes, A. P. (August 2013). "An investigation into the radial velocity variability of GJ 581: On the significance of GJ 581g". Astronomische Nachrichten. 334 (7): 616. arXiv:1307.1246. Bibcode:2013AN....334..616H. doi:10.1002/asna.201311913. S2CID 119186582.

- ^ a b c d Chung, Emily (July 4, 2014). "Earth-like planets Gliese 581g and d likely don't exist, study says". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Mendez, Abel. "False Starts: Potentially Habitable Exoplanets". Planetary Habitability Laboratory. University of Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Anglada-Escudé, Guillem; Tuomi, Mikko (6 March 2015). "Comment on "Stellar activity masquerading as planets in the habitable zone of the M dwarf Gliese 581"". Science. 347 (6226): 1080–b. arXiv:1503.01976. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1080A. doi:10.1126/science.1260796. PMID 25745156. S2CID 5118513.

- ^ "Reanalysis of data suggests 'habitable' planet GJ 581d really could exist". Astronomy Now. March 9, 2015. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Robertson, Paul; Mahadevan, Suvrath; Endl, Michael; Roy, Arpita (2015). "Response to Comment on "Stellar activity masquerading as planets in the habitable zone of the M dwarf Gliese 581"". Science. 347 (6226): 1080. arXiv:1503.02565. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1080R. doi:10.1126/science.1260974. PMID 25745157. S2CID 206562664.

- ^ Suárez Mascareño, A.; et al. (September 2015), "Rotation periods of late-type dwarf stars from time series high-resolution spectroscopy of chromospheric indicators", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 452 (3): 2745–2756, arXiv:1506.08039, Bibcode:2015MNRAS.452.2745S, doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1441, S2CID 119181646.

- ^ Hatzes, Artie P. (January 2016). "Periodic Hα variations in GL 581: Further evidence for an activity origin to GL 581d". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 585: A144. arXiv:1512.00878. Bibcode:2016A&A...585A.144H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527135. S2CID 55623630.

- ^ a b Berardelli, Phil (September 29, 2010). "Astronomers Find Most Earth-like Planet to Date". ScienceNOW. Archived from the original on October 2, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Alpert, Mark (November 7, 2005). "Red Star Rising". Scientific American. 293 (5): 28. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293e..28A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1105-28. PMID 16318021. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Ralph D. Lorenz, Jonathan I Lunine, Paul G. Withers, Christopher P. McKay (2001). "Titan, Mars and Earth: Entropy Production by Latitudinal Heat Transport" (PDF). Ames Research Center, University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joshi, M. M.; Haberle, R. M.; Reynolds, R. T. (October 1997). "Simulations of the Atmospheres of Synchronously Rotating Terrestrial Planets Orbiting M Dwarfs: Conditions for Atmospheric Collapse and the Implications for Habitability". Icarus. 129 (2): 450–465. Bibcode:1997Icar..129..450J. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5793. Archived from the original on 2021-10-18. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ^ Shiga, David (September 29, 2010). "Found: first rocky exoplanet that could host life". New Scientist. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c Pierrehumbert, R. T. (December 27, 2010). "A Palette of climates for Gliese 581g" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal Letters. 726 (1): L8. Bibcode:2011ApJ...726L...8P. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/726/1/L8. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ Heng, Kevin; Vogt, Steven S. (October 25, 2010). "Gliese 581g as a scaled-up version of Earth: atmospheric circulation simulations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 415 (3): 2145–2157. arXiv:1010.4719. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415.2145H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18853.x. S2CID 118428071.

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (November 1, 2010). "Climate Model Suggests Where the Aliens Are". Wired News. Condé Nast Publications. Archived from the original on November 3, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "NASA, Mars: Facts & Figures". Archived from the original on January 23, 2004. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ Mallama, A.; Wang, D.; Howard, R. A. (2006). "Venus phase function and forward scattering from H2SO4". Icarus. 182 (1): 10–22. Bibcode:2006Icar..182...10M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.014.

- ^ Mallama, A. (2007). "The magnitude and albedo of Mars". Icarus. 192 (2): 404–416. Bibcode:2007Icar..192..404M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.07.011.

- ^ [Overview – Mercury – Solar System Exploration: NASA Science https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/mercury/overview/ Archived 2021-04-18 at the Wayback Machine]

- ^ Sagan, C.; Mullen, G. (1972). "Earth and Mars: Evolution of Atmospheres and Surface Temperatures". Science. 177 (4043): 52–56. Bibcode:1972Sci...177...52S. doi:10.1126/science.177.4043.52. PMID 17756316. S2CID 12566286.

- ^ Pavlov, Alexander A.; Kasting, James F.; Brown, Lisa L.; Rages, Kathy A.; Freedman, Richard (May 2000). "Greenhouse warming by CH4 in the atmosphere of early Earth". Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (E5): 11981–11990. Bibcode:2000JGR...10511981P. doi:10.1029/1999JE001134. PMID 11543544.

- ^ Rosing, Minik T.; Bird, Dennis K.; Sleep, Norman H.; Bjerrum, Christian J. (April 1, 2010). "No climate paradox under the faint early Sun". Nature. 464 (7289): 744–747. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..744R. doi:10.1038/nature08955. PMID 20360739. S2CID 205220182.

- ^ "Mars' desert surface..." MGCM Press release. NASA. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ Boyce, J. M.; Mouginis, P.; Garbeil, H. (2005). "Ancient oceans in the northern lowlands of Mars: Evidence from impact crater depth/diameter relationships" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (E03008): n/a. Bibcode:2005JGRE..110.3008B. doi:10.1029/2004JE002328. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth (September 30, 2010). "Could 'Goldilocks' planet be just right for life?". The Washington Post. Nash Holdings LLC. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ "Potentially habitable planet discovered". Carnegie Institution for Science. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

External links

edit- National Science Foundation (2010-09-29). "Steven Vogt and Paul Butler lead a team that discovered the first potentially habitable exoplanet". Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

Video: Steven Vogt of UC Santa Cruz and UC Observatories and Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution of Washington join NSF's Lisa-Joy Zgorski to announce the discovery of the first exoplanet that has the potential to support life.

- "NASA and NSF-Funded Research Finds First Potentially Habitable Exoplanet". Release 10-237. NASA. 2010-09-29. Archived from the original on 2012-08-25. Retrieved 2010-10-01.