Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa (September 26, 1942 – May 15, 2004) was an American scholar of Chicana feminism, cultural theory, and queer theory. She loosely based her best-known book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), on her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border and incorporated her lifelong experiences of social and cultural marginalization into her work. She also developed theories about the marginal, in-between, and mixed cultures that develop along borders, including on the concepts of Nepantla, Coyoxaulqui imperative, new tribalism, and spiritual activism.[1][2] Her other notable publications include This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited with Cherríe Moraga.

Gloria Anzaldúa | |

|---|---|

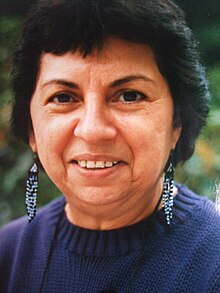

Anzaldúa in 1990 | |

| Born | Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa September 26, 1942 Harlingen, Texas U.S. |

| Died | May 15, 2004 (aged 61) Santa Cruz, California, U.S. |

| Education |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited with Cherríe Moraga; Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987) |

| Signature | |

Early life and education

editAnzaldúa was born in the Rio Grande Valley of south Texas on September 26, 1942, the eldest of four children born to Urbano and Amalia (née García) Anzaldúa. Her great-grandfather, Urbano Sr., once a precinct judge in Hidalgo County, was the first owner of the Jesús María Ranch on which she was born. Her mother grew up on an adjoining ranch, Los Vergeles ("the gardens"), which was owned by her family, and she met and married Urbano Anzaldúa when both were very young. Anzaldúa was a descendant of Spanish settlers to come to the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries. The surname Anzaldúa is of Basque origin. Her paternal grandmother was of Spanish and German ancestry, descending from some of the earliest settlers of the South Texas range country.[3] She has described her father's family as being "very poor aristocracy, but aristocracy anyway" and her mother as "very india, working class, with maybe some black blood which is always looked down on in the valley where I come from."[4]

Anzaldúa wrote that her family gradually lost their wealth and status over the years, eventually being reduced to poverty and being forced into migrant labor, something her family resented because "[t]o work in the fields is the lowest job, and to be a migrant worker is even lower." Her father was a tenant farmer and sharecropper who kept 60% of what he earned, while 40% went to a white-owned corporation called Rio Farms, Inc. Anzaldúa claimed that her family lost their land due to a combination of both "taxes and dirty manipulation" from white people who were buying up land in South Texas through "trickery" and from the behavior of her "very irresponsible grandfather", who lost "a lot of land and money through carelessness". Anzaldúa was left with an inheritance of "a little piece" of 12 acres, which she deeded over to her mother Amalia. Her maternal grandmother Ramona Dávila had amassed land grants from the time Texas was part of Mexico, but the land was lost due to "carelessness, through white peoples' greed, and my grandmother not knowing English".[4]

Anzaldúa wrote that she did not call herself an "india", but still claimed Indigenous ancestry. In "Speaking across the Divide", from The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Reader, she states that her white/mestiza grandmother described her as "pura indita" due to dark spots on her buttocks. Later, Anzaldúa wrote that she "recognized myself in the faces of the braceros that worked for my father. Los braceros were mostly indios from central Mexico who came to work the fields in south Texas. I recognized the Indian aspect of mexicanos by the stories my grandmothers told and by the foods we ate." Despite her family not identifying as Mexican, Anzaldúa believed that "we were still Mexican and that all Mexicans are part Indian." Although Anzaldúa has been criticized by Indigenous scholars for allegedly appropriating Indigenous identity, Anzaldúa claimed that her Indigenous critics had "misread or ... not read enough of my work." Despite claiming to be "three quarters Indian", she also wrote that she was afraid she was "violating Indian cultural boundaries" and afraid that her theories could "unwittingly contribute to the misappropriation of Native cultures" and of "people who live in real Indian bodies." She wrote that while worried that "mestizaje and a new tribalism" could "detribalize" Indigenous peoples, she believed the dialogue was imperative "no matter how risky." Writing about the "Color of Violence" conference organized by Andrea Smith in Santa Cruz, Anzaldúa accused Native American women of engaging in "a lot of finger pointing" because they had argued that non-Indigenous Chicanas' use of Indigenous identity is a "continuation of the abuse of native spirituality and the Internet appropriation of Indian symbols, rituals, vision quests, and spiritual healing practices like shamanism."[5][6]

When she was 11 years old, Anzaldúa's family relocated to Hargill, Texas.[7] She graduated as valedictorian of Edinburg High School in 1962.[8]

She managed to pursue a university education, despite the racism, sexism and other forms of oppression she experienced as a seventh-generation Tejana and Chicana. In 1968, she received a B.A. degree in English, Art, and Secondary Education from University of Texas–Pan American, and an M.A. in English and Education from the University of Texas at Austin. While in Austin, she joined politically active cultural poets and radical dramatists such as Ricardo Sanchez, and Hedwig Gorski.

Career and major works

editAfter obtaining a Bachelor of Arts in English from the Pan American University (now University of Texas Rio Grande Valley), Anzaldúa worked as a preschool and special education teacher. In 1977, she moved to California, where she supported herself through her writing, lectures, and occasional teaching stints about feminism, Chicano studies, and creative writing at San Francisco State University, the University of California, Santa Cruz, Florida Atlantic University, and other universities.

She is perhaps best known for co-editing This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) with Cherríe Moraga, editing Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color (1990), and co-editing This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation (2002). Anzaldúa also wrote the semi-autobiographical Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987). At the time of her death, she was close to completing the book manuscript, Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, which she also planned to submit as her dissertation. It has now been published posthumously by Duke University Press (2015). Her children's books include Prietita Has a Friend (1991), Friends from the Other Side– Amigos del Otro Lado (1993), and Prietita y La Llorona (1996). She also authored many fictional and poetic works.

She made contributions to fields of feminism, cultural theory/Chicana, and queer theory.[9] Her essays are considered foundational texts in the burgeoning field of Latinx philosophy.[10][11][12]

Anzaldúa wrote a speech called "Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers", focusing on the shift towards an equal and just gender representation in literature but away from racial and cultural issues because of the rise of female writers and theorists. She also stressed in her essay the power of writing to create a world that would compensate for what the real world does not offer.[13]

This Bridge Called My Back

editAnzaldúa's essay '"La Prieta" deals with her manifestation of thoughts and horrors that have constituted her life in Texas. Anzaldúa identifies herself as an entity without a figurative home and/or peoples to completely relate to. To supplement this deficiency, Anzaldúa created her own sanctuary, Mundo Zurdo, whereby her personality transcends the norm-based lines of relating to a certain group. Instead, in her Mundo Zurdo, she is like a "Shiva, a many-armed and legged body with one foot on brown soil, one on white, one in straight society, one in the gay world, the man's world, the women's, one limb in the literary world, another in the working class, the socialist, and the occult worlds".[14] The passage describes the identity battles which the author had to engage in throughout her life. Since early childhood, Anzaldúa has had to deal with the challenge of being a woman of color. From the beginnings she was exposed to her own people, to her own family's racism and "fear of women and sexuality".[15] Her family's internalized racism immediately cast her as the "other" because of their bias that being white and fair-skinned means prestige and royalty, when color subjects one to being almost the scum of society (just as her mother had complained about her prieta dating a mojado from Peru). The household she grew up in was one in which the male figure was the authoritarian head, while the female, the mother, was stuck in all the biases of this paradigm. Although this is the difficult position in which white, patriarchal society has cast women of color, gays and lesbians, she does not make them out to be the archenemy, because she believes that "casting stones is not the solution"[16] and that racism and sexism do not come from only whites but also people of color. Throughout her life, the inner racism and sexism from her childhood would haunt her, as she often was asked to choose her loyalties, whether it be to women, to people of color, or to gays/lesbians. Her analogy to Shiva is well-fitted, as she decides to go against these conventions and enter her own world: Mundo Zurdo, which allows the self to go deeper, to transcend the lines of convention and, at the same time, to recreate the self and the society. This is for Anzaldúa a form of religion, one that allows the self to deal with the injustices that society throws at it and to come out a better person, a more reasonable person.

An entry in the book, titled "Speaking In Tongues: A Letter To Third World Women Writers", spotlights the dangers Anzaldúa considers women writers of color deal with, dangers that are rooted in a lack of privileges. She talks about the transformation of writing styles and how we are taught not to air our truths. Folks are outcast as a result of speaking and writing with their native tongues. Anzaldúa wants more women writers of color to be visible and be well represented in text. Her essay compels us to write with compassion and with love. For writing is a form of gaining power by speaking our truths, and it is seen as a way to decolonize, to resist, and to unite women of color collectively within the feminist movement.

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza

editShe is highly known for this autotheoretical book, which discusses her life growing up on the Mexico–Texas border. It was selected as one of the 38 best books of 1987 by Library Journal. Borderlands examines the condition of women in Chicano and Latino culture. Anzaldúa discusses several critical issues related to Chicana experiences: heteronormativity, colonialism, and male dominance. She gives a very personal account of the oppression of Chicana lesbians and talks about the gendered expectations of behavior that normalizes women's deference to male authority in her community. She develops the idea of the "new mestiza" as a "new higher consciousness" that will break down barriers and fight against the male/female dualistic norms of gender. The first half of the book is about isolation and loneliness in the borderlands between cultures. The latter half of the book is poetry. In the book, Anzaldúa uses two variations of English and six variations of Spanish. By doing this, she deliberately makes it difficult for non-bilinguals to read. Language was one of the barriers Anzaldúa dealt with as a child, and she wanted readers to understand how frustrating things are when there are language barriers. The book was written as an outlet for her anger and encourages one to be proud of one's heritage and culture.[17]

In chapter 3 of the book, titled "Entering Into the Serpent", Anzaldúa discusses three key women in Mexican culture – "La Llorona, La Malinche, and Our Lady of Guadalupe – known as the "Three Mothers" (Spanish: Las Tres Madres), and explores their relationship to Mexican culture.[18]

Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality

Anzaldúa wrote Light in the Dark during the last decade of her life. Drawn from her unfinished dissertation for her PhD in Literature from University of California, Santa Cruz, the book is carefully organized from The Gloria Anzaldúa Papers, 1942–2004 by AnaLouise Keating, Anzaldúa's literary trustee. The book represents her most developed philosophy.[19] Throughout Light in the Dark, Anzaldúa weaves personal narratives into deeply engaging theoretical readings to comment on numerous contemporary issues—including the September 11 attacks, neocolonial practices in the art world, and coalitional politics. She valorizes subaltern forms and methods of knowing, being, and creating that have been marginalized by Western thought, and theorizes her writing process as a fully embodied artistic, spiritual, and political practice. Light in the Dark contains multiple transformative theories including include the nepantleras, the Coyolxauhqui imperative (named for the Aztec goddess Coyolxāuhqui), spiritual activism, and others.

Themes in writing

editNepantilism

editAnzaldúa drew on Nepantla, a Nahuatl word that means "in the middle", to conceptualize her experience as a Chicana woman. She coined the term "Nepantlera". "Nepantleras are threshold people; they move within and among multiple, often conflicting, worlds and refuse to align themselves exclusively with any single individual, group, or belief system."[20]

Spirituality

editAnzaldúa described herself as a very spiritual person and stated that she experienced four out-of-body experiences during her lifetime. In many of her works, she referred to her devotion to la Virgen de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), Nahuatl/Toltec divinities, and to the Yoruba orishás Yemayá and Oshún.[21] In 1993, she expressed regret that scholars had largely ignored the "unsafe" spiritual aspects of Borderlands and bemoaned the resistance to such an important part of her work.[22] In her later writings, she developed the concepts of spiritual activism and nepantleras to describe the ways contemporary social actors can combine spirituality with politics to enact revolutionary change.

Anzaldúa has written about the influence of hallucinogenic drugs on her creativity, particularly psilocybin mushrooms. During one 1975 psilocybin mushroom trip when she was "stoned out of my head", she coined the term "the multiple Glorias" or the "Gloria Multiplex" to describe her feeling of multiplicity, an insight that influenced her later writings.[23]

Language and "linguistic terrorism"

editAnzaldua's works weave English and Spanish together as one language, an idea stemming from her theory of "borderlands" identity. Her autobiographical essay "La Prieta" was published in (mostly) English in This Bridge Called My Back, and in (mostly) Spanish in Esta puente, mi espalda: Voces de mujeres tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos. In her writing, Anzaldúa uses a unique blend of eight dialects, two variations of English and six of Spanish. In many ways, by writing in a mix of languages, Anzaldúa creates a daunting task for the non-bilingual reader to decipher the full meaning of the text. Language, clearly one of the borders Anzaldúa addressed, is an essential feature to her writing. Her book is dedicated to being proud of one's heritage and to recognizing the many dimensions of her culture.[7]

Anzaldúa emphasized in her writing the connection between language and identity. She expressed dismay with people who gave up their native language in order to conform to the society they were in. Anzaldúa was often scolded for her improper Spanish accent and believed it was a strong aspect to her heritage; therefore, she labels the qualitative labeling of language "linguistic terrorism."[24] She spent a lot of time promoting acceptance of all languages and accents.[25] In an effort to expose her stance on linguistics and labels, Anzaldúa explained, "While I advocate putting Chicana, tejana, working-class, dyke-feminist poet, writer theorist in front of my name, I do so for reasons different than those of the dominant culture... so that the Chicana and lesbian and all the other persons in me don't get erased, omitted, or killed."[26]

Despite the connection between language and identity, Anzaldúa also highlighted that language is a bridge that linked mainstream communities and marginalized communities.[27] She claimed language is a tool that identifies marginalized communities, represents their heritage and cultural backgrounds. The connection which language created is two-way, it not only encourage marginalized communities to express themselves, but also calls on mainstream communities to engage with the language and culture of marginalized communities.

Health, body, and trauma

editAnzaldúa experienced at a young age, symptoms of the endocrine condition that caused her to stop growing physically at the age of twelve.[28] As a child, she would wear special girdles fashioned for her by her mother in order to disguise her condition. Her mother would also ensure that a cloth was placed in Anzaldúa's underwear as a child in case of bleeding. Anzaldúa remembers, "I'd take [the bloody cloths] out into this shed, wash them out, and hang them really low on a cactus so nobody would see them.... My genitals... [were] always a smelly place that dripped blood and had to be hidden." She eventually underwent a hysterectomy in 1980 when she was 38 years old to deal with uterine, cervical, and ovarian abnormalities.[22]

Anzaldúa's poem "Nightvoice" alludes to a history of child sexual abuse, as she writes: "blurting out everything how my cousins/took turns at night when I was five eight ten."[29]

Mestiza/Border Culture

editOne of Anzaldúa's major contributions was her introduction to United States academic audiences of the term mestizaje, meaning a state of being beyond binary ("either-or") conception, into academic writing and discussion. In her theoretical works, Anzaldúa called for a "new mestiza," which she described as an individual aware of her conflicting and meshing identities and uses these "new angles of vision" to challenge binary thinking in the Western world. The "borderlands" that she refers to in her writing are geographical as well as a reference to mixed races, heritages, religions, sexualities, and languages. Anzaldúa is primarily interested in the contradictions and juxtapositions of conflicting and intersecting identities. She points out that having to identify as a certain, labelled, sex can be detrimental to one's creativity as well as how seriously people take you as a producer of consumable goods.[30] The "new mestiza" way of thinking is illustrated in postcolonial feminism.[31] In education, Anzaldúa's practice of border challenges the traditionally structured binary understanding of gender.[32] It recognizes gender identity is not fixed or singular concept but rather a complex terrain. Encouraged educators to provide a safe and open platform for students to learn, recognize, and identify themselves comfortably.

Anzaldúa called for people of different races to confront their fears to move forward into a world that is less hateful and more useful. In "La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness," a text often used in women's studies courses, Anzaldúa insisted that separatism invoked by Chicanos/Chicanas is not furthering the cause but instead keeping the same racial division in place. Many of Anzaldúa's works challenge the status quo of the movements in which she was involved. She challenged these movements in an effort to make real change happen to the world rather than to specific groups. Scholar Ivy Schweitzer writes, "her theorizing of a new borderlands or mestiza consciousness helped jump start fresh investigations in several fields -- feminist, Americanist [and] postcolonial."[33]

Sexuality

editIn the same way that Anzaldúa often wrote that she felt that she could not be classified as only part of one race or the other, she felt that she possessed a multi-sexuality. When growing up, Anzaldúa expressed that she felt an "intense sexuality" towards her own father, children, animals, and even trees. AnaLouise Keating considered omitting Anzaldúa's sexual fantasies involving incest and bestiality for being "rather shocking" and "pretty radical", but Anzaldúa insisted that they remain because "to me, nothing is private." Anzaldúa claimed she had "sexual fantasies about father-daughter, sister-brother, woman-dog, woman-wolf, woman-jaguar, woman-tiger, or woman-panther. It was usually a cat- or dog-type animal." Anzaldúa also specified that she may have "mistaken this connection, this spiritual connection, for sexuality." She was attracted to and later had relationships with both men and women. Although she identified herself as a lesbian in most of her writing and had always experienced attraction to women, she also wrote that lesbian was "not an adequate term" to describe herself. She stated that she "consciously chose women" and consciously changed her sexual preference by changing her fantasies, arguing that "You can change your sexual preference. It's real easy." She stated that she "became a lesbian in my head first, the ideology, the politics, the aesthetics" and that the "touching, kissing, hugging, and all came later".[22] Anzaldúa wrote extensively about her queer identity and the marginalization of queer people, particularly in communities of color.[34]

Feminism

editAnzaldúa self-identifies in her writing as a feminist, and her major works are often associated with Chicana feminism and postcolonial feminism. Anzaldúa writes of the oppression she experiences specifically as a woman of color, as well as the restrictive gender roles that exist within the Chicano community. In Borderlands, she also addresses topics such as sexual violence perpetrated against women of color.[35] Her theoretical work on border culture is considered a precursor to Latinx Philosophy.[36]

Criticism

editAnzaldúa has been criticized for neglecting and erasing Afro-Latino and Afro-Mexican history, as well as for drawing inspiration from José Vasconcelos' La raza cósmica without critiquing the racism, anti-blackness, and eugenics within the work of Vasconcelos.[37]

Josefina Saldaña-Portillo's 2001 essay "Who's the Indian in Aztlán?" criticizes the "indigenous erasure" in the work of Anzaldúa as well as Anzaldúa's "appropriation of state sponsored Mexican indigenismo."[38] Juliet Hooker in "Hybrid subjectivities, Latin American mestizaje, and Latino political thought on race" also describes some of Anzaldúa's work as, "deploy[ing] an overly romanticized portrayal of indigenous peoples that looks onto the past rather than contemporary indigenous movements".[39]

Awards

edit- Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award (1986) – This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color[40]

- Lambda Lesbian Small Book Press Award (1991)[41]

- Lesbian Rights Award (1991)[42]

- Sappho Award of Distinction (1992)[42]

- National Endowment for the Arts Fiction Award (1991)[43]

- American Studies Association Lifetime Achievement Award (Bode-Pearson Prize – 2001).[44]

Additionally, her work Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza was recognized as one of the 38 best books of 1987 by Library Journal and 100 Best Books of the Century by both Hungry Mind Review and Utne Reader.

In 2012, she was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the LGBT History Month.[45]

Death and legacy

editAnzaldúa died on May 15, 2004, at her home in Santa Cruz, California, from complications of diabetes. At the time of her death, she was working toward the completion of her dissertation to receive her doctorate in Literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz.[46] It was awarded posthumously in 2005.

The Chicana/o Latina/o Research Center (CLRC) at University of California, Santa Cruz offers the annual Gloria E. Anzaldúa Distinguished Lecture Award and The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Award for Independent Scholars and Contingent Faculty is offered annually by the American Studies Association. The latter "...honors Anzaldúa's outstanding career as an independent scholar and her labor as contingent faculty, along with her groundbreaking contributions to scholarship on women of color and to queer theory. The award includes a lifetime membership in the ASA, a lifetime electronic subscription to American Quarterly, five years access to the electronic library resources at the University of Texas at Austin, and $500".[47]

In 2007, three years after Anzaldúa's death, the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa (SSGA) was established to gather scholars and community members who continue to engage Anzaldúa's work. The SSGA co-sponsors a conference – El Mundo Zurdo – every 18 months.[48]

The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Poetry Prize is awarded annually, in conjunction with the Anzaldúa Literary Trust, to a poet whose work explores how place shapes identity, imagination, and understanding. Special attention is given to poems that exhibit multiple vectors of thinking: artistic, theoretical, and social, which is to say, political. First place is publication by Newfound, including 25 contributor copies, and a $500 prize.[49]

The National Women's Studies Association honors Anzaldúa, a valued and long-active member of the organization, with the annual Gloria E. Anzaldúa Book Prize, which is designated for groundbreaking monographs in women's studies that makes significant multicultural feminist contributions to women of color/transnational scholarship.[50]

To commemorate what would have been Anzaldúa's 75th birthday, on September 26, 2017 Aunt Lute Books published the anthology Imaniman: Poets Writing in the Anzaldúan Borderlands edited by ire'ne lara silva and Dan Vera with an introduction by United States Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera[51] and featuring the work of 52 contemporary poets on the subject of Anzaldúa's continuing impact on contemporary thought and culture.[52] On the same day, Google commemorated Anzaldúa's achievements and legacy through a Doodle in the United States.[53][54]

Archives

editHoused at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin, the Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Papers, 1942-2004 contains over 125 feet of published and unpublished materials including manuscripts, poetry, drawings, recorded lectures, and other archival resources.[55] AnaLouise Keating is one of the Anzaldúa Trust's trustees. Anzaldúa maintained a collection of figurines, masks, rattles, candles, and other ephemera used as altar (altares) objects at her home in Santa Cruz, California. These altares were an integral part of her spiritual life and creative process as a writer.[56] The altar collection is presently housed by the Special Collections department of the University Library at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Works

edit- This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), co-edited with Cherríe Moraga, 4th ed., Duke University Press, 2015. ISBN 0-943219-22-1.

- Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), 4th ed., Aunt Lute Books, 2012. ISBN 1-879960-12-5.

- Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color, Aunt Lute Books, 1990. ISBN 1-879960-10-9.

- Interviews/Entrevistas, edited by AnaLouise Keating, Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-92503-7.

- This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation, co-edited with AnaLouise Keating, Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-93682-9.

- The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, edited by AnaLouise Keating. Duke University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8223-4564-0.

- Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, edited by AnaLouise Keating, Duke University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8223-6009-4.

Children's books

edit- Prietita Has a Friend (1991)

- Friends from the Other Side/Amigos del Otro Lado (1995)

- Prietita y La Llorona (1996)

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ Keating, AnaLouise (2006). "From Borderlands and New Mestizas to Nepantlas and Nepantleras: Anzaldúan Theories for Social Change" (PDF). Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge. IV. Ahead Publishing House. ISSN 1540-5699. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ Keating, AnaLouise (2008). ""I'm a Citizen of the Universe": Gloria Anzaldúa's Spiritual Activism as Catalyst for Social Change". Feminist Studies. 34 (1/2): 53–54. JSTOR 20459180 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "La Prieta" (PDF). This Bridge Called My Back. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Anzaldúa, Gloria E. (2000). Interviews/Entrevistas. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781000082807.

- ^ "Speaking across the Divide (The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader)" (PDF). Duke University Press. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "La Prieta (This Bridge Called My Back)" (PDF). Persephone Press. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "Gloria Anzaldúa". Voices From the Gaps, University of Minnesota. (handle link: 167856). Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "History | UTRGV".

- ^ "Chicana Feminism – Theory and Issues". www.umich.edu. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Pitts, Andrea J.; Ortega, Mariana; Medina, José, eds. (2020). Theories of the flesh : Latinx and Latin American feminisms, transformation, and resistance. New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-006300-9. OCLC 1141418176.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Alessandri, Mariana (2020). "Gloria Anzaldúa as philosopher: The early years (1962–1987)". Philosophy Compass. 15 (7): e12687. doi:10.1111/phc3.12687. ISSN 1747-9991. S2CID 225512450.

- ^ Ortega, Mariana (March 14, 2016). In-between : Latina feminist phenomenology, multiplicity, and the self. Albany, New York. ISBN 978-1-4384-5977-6. OCLC 908287035.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Keating (ed.), The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader (2009), pp. 26–36.

- ^ (205)

- ^ (198)

- ^ (207)

- ^ "Gloria Anzaldúa". www.uhu.es. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Anzaldúa, Gloria. "La Llorona, La Malinche, y La Virgen de Guadalupe". Tumblr. 2005. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "Light in the Dark⁄Luz en lo Oscuro". Duke University Press. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Keating, AnaLouise (2006). "From Borderlands and New Mestizas to Nepantlas and Nepantleras Anzaldúan Theories for Social Change" (PDF).

- ^ Anzaldúa, Gloria E. Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rethinking Identity, Spirituality, Reality. Durham and London: Duke, 2015.

- ^ a b c Anzaldúa, Gloria, with AnaLouise Keating. Interviews/Entrevistas. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- ^ "Interviews/Entrevistas". Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ What is Linguistic Terrorism?, The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Foundation

- ^ About Gloria, The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Foundation

- ^ Anzaldúa, G. (1998). "To(o) Queer the Writer—Loca, escritora y chicana." In C. Trujillo (Ed.), Living Chicana Theory (pp. 264). San Antonio, TX: Third Woman Press.

- ^ Li. (2023). p.2 of Interview.

- ^ Anzaldúa, Gloria, "La Prieta," The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, ed. AnaLouise Keating, Duke University Press, 2009, p. 39.

- ^ Dahms, Elizabeth Anne (2012). "The Life and Works of Gloria E. Anzaldúa: An Intellectual Biography". University of Kentucky. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Gloria Anzaldúa, "To(o) Queer the Writer—Loca, escritoria y chicana", Invasions; writings by Queers, Dykes and Lesbians, 1994

- ^ Mahraj (2010). "Dis/Locating the Margins: Gloria Anzaldua and Dynamic Feminist Learning". Feminist Teacher. 21 (1): 1–20. doi:10.5406/femteacher.21.1.0001. JSTOR 10.5406/femteacher.21.1.0001. S2CID 145378450.

- ^ Li. (2023). p.2 of Interview

- ^ Schweitzer, Ivy (January 2006). "For Gloria Anzaldúa: Collecting America, Performing Friendship". PMLA. 121 (1, Special Topic: The History of the Book and the Idea of Literature): 285–291. doi:10.1632/003081206x129774. S2CID 162069788.

- ^ Hedrick, Tace (September 1, 2009). "Queering the Cosmic Race: Esotericism, Mestizaje, and Sexuality in the Work of Gabriela Mistral and Gloria Anzaldúa". Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. 34 (2): 67–98. doi:10.1525/azt.2009.34.2.67. Retrieved September 26, 2017 – via IngentaConnect.

- ^ Anzaldua, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

- ^ Sanchez, Robert Eli Jr., ed. (2019). Latin American and Latinx philosophy : a collaborative introduction. New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-138-29585-8. OCLC 1104214542.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Mexican Is Not a Race". The New Inquiry. April 6, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Indian Given". The Syndicate Network. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ Hooker, Juliet (April 3, 2014). "Hybrid subjectivities, Latin American mestizaje, and Latino political thought on race". Politics, Groups, and Identities. 2 (2): 188–201. doi:10.1080/21565503.2014.904798. ISSN 2156-5503.

- ^ American Booksellers Association (2013). "The American Book Awards / Before Columbus Foundation [1980–2012]". BookWeb. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

1986 [...] A Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua

- ^ "Book Awards -- Lambda Literary Awards". www.readersread.com. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Day, Frances Ann (2003). "Gloria Anzaldúa". Latina and Latino Voices in Literature: Lives and Works. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-313-32394-2.

- ^ NEA_lit_mech_blue.indd Archived June 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ASA Awards and Prizes – ASA". www.theasa.net. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "Gloria Andzaldua biography". LGBT History Month.

- ^ "Classes without Quizzes". currents.ucsc.edu. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "The Gloria E. Anzaldúa Award for Independent Scholars and Contingent Faculty 2010 – American Studies Association". Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa". About the SSGA. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ "Gloria E. Anzaldúa Poetry Prize". April 4, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "NWSA". www.nwsa.org. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Echeverria, Olga Garcia (February 26, 2017). "La Bloga: Imaniman: Sparked From the Communal Soul". Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "Imaniman | Aunt Lute". Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ "Gloria E. Anzaldúa". YouTube.com. September 25, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Google Doodle Celebrates Gloria E. Anzaldúa's Birthday. Here's What to Know About Her". Time. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ "Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Papers, 1942–2004". www.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Cited in the Biography section of the UCSC finding aid.

General and cited references

edit- Adams, Kate. "Northamerican Silences: History, Identity, and Witness in the Poetry of Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga, and Leslie Marmon Silko." Eds. Elaine Hedges and Shelley Fisher Fishkin. Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism. NY: Oxford UP, 1994. 130–145. Print.

- Alarcón, Norma. "Anzaldúa's Frontera: Inscribing Gynetics." Eds. Smadar Lavie and Ted Swedenburg. Displacement, Diaspora, and Geographies of Identity. Durham: Duke UP, 1996. 41–52. Print

- Alcoff, Linda Martín. "The Unassimilated Theorist." PMLA 121.1 (2006): 255–259 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Almeida, Sandra Regina Goulart. "Bodily Encounters: Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands / La Frontera." Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of Language and Literature 39 (2000): 113–123. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria E., 2003. "La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a New Consciousness", pp. 179–87, in Carole R. McCann and Seung-Kyung Kim (eds), Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, New York: Routledge.

- Bacchetta, Paola. "Transnational Borderlands. Gloria Anzaldúa's Epistemologies of Resistance and Lesbians 'of Color' in Paris." In El Mundo Zurdo: Selected Works from the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa 2007 to 2009, edited by Norma Cantu, Christina L. Gutierrez, Norma Alarcón and Rita E. Urquijo-Ruiz, 109–128. San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 2010.

- Barnard, Ian. "Gloria Anzaldúa's Queer Mestizaje." MELUS 22.1 (1997): 35–53 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Blend, Benay. "'Because I Am in All Cultures at the Same Time': Intersections of Gloria Anzaldúa's Concept of Mestizaje in the Writings of Latin-American Jewish Women." Postcolonial Text 2.3 (2006): 1–13. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Keating, AnaLouise, and Gloria Gonzalez-Lopez, eds. Bridging: How Gloria Anzaldua's Life and Work Transformed Our Own (University of Texas Press; 2011), 276 pp.

- Bornstein-Gómez, Miriam. "Gloria Anzaldúa: Borders of Knowledge and (re)Signification." Confluencia 26.1 (2010): 46–55 EBSCO Host. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Capetillo-Ponce, Jorge. "Exploring Gloria Anzaldúa’s Methodology in Borderlands/La Frontera—The New Mestiza." Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 4.3 (2006): 87–94 Scholarworks UMB. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Castillo, Debra A.. "Anzaldúa and Transnational American Studies." PMLA 121.1 (2006): 260–265 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- David, Temperance K. "Killing to Create: Gloria Anzaldúa's Artistic Solution to 'Cervicide'" Intersections Online 10.1 (2009): 330–40. WAU Libraries. Web. July 9, 2012.

- Donadey, Anne. "Overlapping and Interlocking Frames for Humanities Literary Studies: Assia Djebar, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Gloria Anzaldúa." College Literature 34.4 (2007): 22–42 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Enslen, Joshua Alma. "Feminist prophecy: a Hypothetical Look into Gloria Anzaldúa's 'La Conciencia de la Mestiza: Towards a new Consciousness' and Sara Ruddick's 'Maternal Thinking.'" LL Journal 1.1 (2006): 53-61 OJS. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Fishkin, Shelley Fisher. "Crossroads of Cultures: The Transnational Turn in American Studies--Presidential Address to the American Studies Association, November 12, 2004." American Quarterly 57.1 (2005): 17–57. Project Muse. Web. February 10, 2010.

- Friedman, Susan Stanford. Mappings: Feminism and the Cultural Geographies of Encounter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1998. Print.

- Hartley, George. "'Matriz Sin Tumba': The Trash Goddess and the Healing Matrix of Gloria Anzaldúa's Reclaimed Womb." MELUS 35.3 (2010): 41–61 Project Muse. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Hedges, Elaine and Shelley Fisher Fishkin eds. Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism. NY: Oxford UP, 1994. Print.

- Hedley, Jane. "Nepantilist Poetics: Narrative and Cultural Identity in the Mixed-Language Writings of Irena Klepfisz and Gloria Anzaldúa." Narrative 4.1 (1996): 36–54 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Herrera-Sobek, María. "Gloria Anzaldúa: Place, Race, Language, and Sexuality in the Magic Valley." PMLA 121.1 (2006): 266-271 JSTOR Web. August 21, 2012.

- Hilton, Liam. "Peripherealities: Porous Bodies; Porous Borders: The 'Crisis' of the Transient in a Borderland of Lost Ghosts." Graduate Journal of Social Science 8.2 (2011): 97–113. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Keating, AnaLouise, ed. EntreMundos/AmongWorlds: New Perspectives on Gloria Anzaldúa. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.

- Keating, AnaLouise. Women Reading, Women Writing: Self-Invention in Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa and Audre Lorde. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996.

- Lavie, Smadar and Ted Swedenburg eds. Displacement, Diaspora, and Geographies of Identity. Durham: Duke UP, 1996. Print.

- Lavie, Smadar. "Staying Put: Crossing the Israel–Palestine Border with Gloria Anzaldúa." Anthropology and Humanism Quarterly, June 2011, Vol. 36, Issue 1. This article won the American Studies Association's 2009 Gloria E. Anzaldúa Award for Independent Scholars.

- Mack-Canty, Colleen. "Third-Wave Feminism and the Need to Reweave the Nature/Culture Duality" pp. 154–79, in NWSA Journal, Fall 2004, Vol. 16, Issue 3.

- Lioi, Anthony. "The Best-Loved Bones: Spirit and History in Anzaldúa's 'Entering into the Serpent.'" Feminist Studies 34.1/2 (2008): 73–98 JSTOR. Web. August 27, 2012.

- Lugones, María. "On Borderlands / La Frontera: An Interpretive Essay." Hypatia 7.4 (1992): 31–37 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Martinez, Teresa A.. "Making Oppositional Culture, Making Standpoint: A Journey into Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands." Sociological Spectrum 25 (2005): 539–570 Tayor & Francis. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Negrón-Muntaner, Frances. "Bridging Islands: Gloria Anzaldúa and the Caribbean." PMLA 121,1 (2006): 272–278 MLA. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Pérez, Emma. "Gloria Anzaldúa: La Gran Nueva Mestiza Theorist, Writer, Activist-Scholar" pp. 1–10, in NWSA Journal; Summer 2005, Vol. 17, Issue 2.

- Ramlow, Todd R.. "Bodies in the Borderlands: Gloria Anzaldúa and David Wojnarowicz's Mobility Machines." MELUS 31.3 (2006): 169–187 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Rebolledo, Tey Diana. "Prietita y el Otro Lado: Gloria Anzaldúa's Literature for Children." PMLA 121.1 (2006): 279–784 JSTOR. Web. April 3, 2012.

- Reuman, Ann E. "Coming Into Play: An Interview with Gloria Anzaldua" p. 3, in MELUS; Summer 2000, Vol. 25, Issue 2.

- Saldívar-Hull, Sonia. "Feminism on the Border: From Gender Politics to Geopolitics." Criticism in the Borderlands: Studies in Chicano Literature, Culture, and Ideology. Eds. Héctor Calderón and José´David Saldívar. Durham: Duke UP, 1991. 203–220. Print.

- Schweitzer, Ivy. "For Gloria Anzaldúa: Collecting America, Performing Friendship." PMLA 121.1 (2006): 285–291 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Smith, Sidonie. Subjectivity, Identity, and the Body: Women's Autobiographical Practices in the Twentieth Century. Bloomington, IN: IN UP, 1993. Print.

- Solis Ybarra, Priscilla. "Borderlands as Bioregion: Jovita González, Gloria Anzaldúa, and the Twentieth-Century Ecological Revolution in the Rio Grande Valley." MELUS 34.2 (2009): 175–189 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

- Spitta, Silvia. Between Two Waters: Narratives of Transculturation in Latin America (Rice UP 1995; Texas A&M 2006)

- Stone, Martha E. "Gloria Anzaldúa" pp. 1, 9, in Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide; January/February 2005, Vol. 12, Issue 1.

- Vargas-Monroy, Liliana. "Knowledge from the Borderlands: Revisiting the Paradigmatic Mestiza of Gloria Anzaldúa." Feminism and Psychology 22.2 (2011): 261–270 SAGE. Web. August 24, 2012.

- Vivancos Perez, Ricardo F. doi:10.1057/9781137343581 Radical Chicana Poetics. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Ward, Thomas. "Gloria Anzaldúa y la lucha fronteriza", in Resistencia cultural: La nación en el ensayo de las Américas, Lima, 2004, pp. 336–42.

- Yarbro-Bejarano, Yvonne. "Gloria Anzaldúa's Borderlands / La Frontera: Cultural Studies, 'Difference' and the Non-Unitary Subject." Cultural Critique 28 (1994): 5–28 JSTOR. Web. August 21, 2012.

Further reading

edit- Broe, Mary Lynn; Ingram, Angela (1989). Women's writing in exile. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807842515.

- Castillo, Debra A. (2005). Redreaming America: Toward a Bilingual American Culture. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 1-4237-4364-4. OCLC 62750478.

- González, Christopher (2017). Permissible Narratives: The Promise of Latino/a Literature. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-1350-6. OCLC 975447664.

- Zaytoun, Kelli D. (2022). Shapeshifting Subjects: Gloria Anzaldúa's Naguala and Border Arte. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. doi:10.5622/illinois/9780252044434.001.0001. ISBN 9780252044434.

- Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez, "Gloria E. Anzaldúa"

- Perez, Rolando (2020). "The Bilingualisms of Latino-a Literatures". In Stavans, Ilan (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Latino Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-069120-2. OCLC 1121419672.

External links

edit- Voices from the Gaps biography

- San Francisco Chronicle Obituary for Gloria Anzaldúa

- "Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldua" Archived May 6, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- "Gloria Anzaldua Legacy Project – MySpace"

- Finding aid for the Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Papers, 1942-2004

- Finding aid for the Gloria Anzaldúa Altares Collection

- "La prieta", ensayo autobiográfico, de la antología Esta puente, mi espalda

- Some of Anzaldua's work has been translated into French by Paola Bacchetta and Jules Falquet in a special issue of the French journal Cahiers du CEDREF on "Decolonial Feminist and Queer Theories: Ch/Xicana and U.S. Latina Interventions" that they co-edited with Norma Alarcon; available at Les Cahiers du CEDREF.

- Gloria Anzaldúa and Philosophy: The Concept/Image of the Mestiza—by Rolando Pérez This article is part of a dossier on GLORIA ANZALDUA edited by Ricardo F. Vivancos for Cuadernos de ALDEEU, Volume 34, Spring 2019.