Maynard is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The town is located 22 miles west of Boston, in the MetroWest and Greater Boston region of Massachusetts and borders Acton, Concord, Stow and Sudbury. The town's population was 10,746 as of the 2020 United States Census.[1]

Maynard, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Nason Street in historic downtown Maynard | |

| Motto(s): Progressus cum Stabilitate (Latin) "Progress with Stability" | |

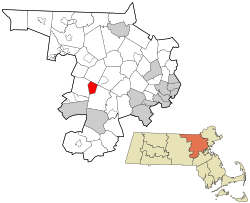

Location in Middlesex County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°26′00″N 71°27′00″W / 42.43333°N 71.45000°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Middlesex |

| Settled | 1638 |

| Incorporated | 1871 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.4 sq mi (13.9 km2) |

| • Land | 5.2 sq mi (13.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 186 ft (57 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 10,746 |

| • Density | 2,066.54/sq mi (790.15/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 01754 |

| Area code | 351/978 |

| FIPS code | 25-39625 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0618229 |

| Website | www.townofmaynard-ma.gov |

Maynard is located on the Assabet River, a tributary of the Concord River. A large part of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge is located within the town, and the Assabet River Rail Trail connects the Refuge and downtown Maynard to the South Acton commuter rail station.[2][3] Historic downtown Maynard is home to many shops, restaurants, galleries, a movie theater, and the former Assabet Woolen Mill, which produced wool fabrics from 1846 to 1950, including cloth for Union Army uniforms during the Civil War. Maynard was the headquarters for Digital Equipment Corporation from 1957 to 1998. Owners of the former mill complex currently lease space to office and light-industry businesses.

History

editMaynard, located on the Assabet River, was first settled as a farming community by Puritan colonists in the 1600s who acquired the land comprising modern-day Maynard from local Native American tribe members who referred to the area as Pompositicut or Assabet.[5] In 1651 Tantamous ("Old Jethro") transferred land in what is now Maynard to Herman Garrett by defaulting on a mortgaged mare and colt, and in 1684 Tantamous' son Peter Jethro, a praying Indian, and Jehojakim and ten others transferred further land in the area to the settlers.[6] In 1676 during King Philip's War, Native Americans gathered on Pompasitticut Hill (later known as Summer Hill) to plan an attack on Sudbury.[6] There is a story, unconfirmed by any evidence, that pirates briefly stayed at the Thomas Smith farm on Great Road, circa 1720, buried treasure nearby, and departed, never to return.[7]

Residents of what is now Maynard fought in the Revolutionary War, including Luke Brooks of Summer Street who was in the Stow militia company which marched to Concord on April 19, 1775.[8] In 1851 transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau wrote about his walk through the area in his famous journal.[9] and he published a poem about Old Marlboro Road, part of which runs through Maynard.[10] During the American Civil War, at least thirty-six residents of Assabet Village fought for the Union.[6]

The area now known as Maynard was originally known as "Assabet Village" and was then part of the towns of Stow and Sudbury.[5] The Town of Maynard was incorporated as an independent municipality in 1871. There were some exploratory town-founding rumblings in 1870, followed by a petition to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, filed January 26, 1871. State approval was granted April 19, 1871. In return, the new town paid Sudbury and Stow about $23,600 and $8,000 respectively. Sudbury received more money because more land came from Sudbury and Sudbury owned shares in the railroad, and the wool mill and paper mill were located in Sudbury. The population of the newly formed town—at 1,820—was larger than either of its parent towns.[11]

Formation of new towns carved out of older ones was not unique to Maynard. Nearby Hudson, with its cluster of leather processing and shoe-making mills, seceded from Marlborough and Stow in 1866. In fact, the originally much larger Stow formed in 1683 lost land to Harvard, Shirley, Boxborough, Hudson and Maynard. The usual reason to petition the State's Committee on Towns was that a fast-growing population cluster—typically centered around mills—was too far from the schools, churches and Meeting Hall of the parent town.[12]

The community was named after Amory Maynard, the man who, with William Knight, had bought water-rights to the Assabet River, installed a dam and built a large carpet mill in 1846–1847. The community grew along with the Assabet Woolen Mill and made wool cloth for U.S. military uniforms for the Civil War. Further downstream along the Assabet, the American Powder Mills complex manufactured gunpowder from 1835 to 1940.[13] The woolen mill went bankrupt in 1898; it was purchased in 1899 by the American Woolen Company, a multi-state corporation, which greatly modernized and expanded the mill complex from 1900 through 1919.

There was an attempt in 1902 to change the town's name from "Maynard" to "Assabet". Some townspeople were upset that Amory Maynard had not left the town a gift before he died in 1890, and more were upset that Lorenzo Maynard, Amory's son, had withdrawn his own money from the Mill before it went bankrupt in 1898. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts decided to keep the name as "Maynard" without allowing the topic to come to a vote by the residents.[6][13]

In the early twentieth century, the village of Maynard was more modern and urbanized than many of the surrounding areas, and people would visit Maynard to shop, including Babe Ruth who lived in nearby Sudbury during the baseball off-season, and would visit Maynard to buy cigars and play pool at pool halls on Main Street. The town had a train station, an electric trolley, hotels and movie halls.[13]

In 1942 the U.S. Army seized one-fifth of the town's land area, from the south side, to create a munitions storage facility. Land owners were evicted. The land remained military property for years. In 2005 it became part of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge.[2][14]

After the woolen mill finally shut down in 1950, a Worcester-based group of businessmen bought the property in July 1953 and began leasing it as office or manufacturing space. Major tenants included Raytheon and Dennison Manufacturing Company. Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) moved into the complex in 1957, initially renting only 8,680 square feet (806 m2) for $300/month. The company grew and grew until it bought the entire complex in 1974, which led to Maynard's nickname "Mini Computer Capital of the World". DEC remained in Maynard until 1998 when it was purchased by Compaq, which was itself later bought out by Hewlett-Packard in 2002.[15]

"The Mill", as locals call it, was renovated in the late 1990s and renamed "Clock Tower Place" (2000–2015), and then renamed "Mill & Main Place" by new owners in 2016. The site houses many businesses, including the headquarters of Powell Flutes. The mill complex is also home to the oldest, still-working, hand-wound clock in the country (see image). The clock tower was constructed in 1892 by Lorenzo Maynard as a gift to the town. The weights that power the E. Howard & Co. tower clock and bell-ringing mechanisms are wound up once a week – more than 6,000 times since the clock was installed. The process takes one to two hours. The four clock faces have always been illuminated by electric lights.[11] For three months a year the Mill parking lot adjacent to Main Street is used on Saturdays for the Maynard Community Farmers' Market.[16]

Glenwood Cemetery (incorporated 1871), located south of downtown Maynard, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. This still-active cemetery is the site of approximately 7,000 burials. On its east side it abuts St. Bridget's Cemetery, also in Maynard.

The Maynard family

editJohn Maynard, born 1598, emigrated from England with his wife Elizabeth (Ashton) Maynard around 1635. Five generations later, Isaac Maynard was operating a mill in Marlborough. When he died in 1820 at age 41 his teenage son, Amory Maynard, took over the family business. The City of Boston bought Amory's water rights to Fort Meadow Pond in 1846. He partnered with William Knight to start up a woolen mill operation on the Assabet River. Amory and his wife Mary (Priest) Maynard had three sons: Lorenzo (1829–1904), William (1833–1906) and Harlan (1843–1861). Amory managed the mill from 1847 to 1885 (Knight retired in 1852). Lorenzo took over from 1885 to 1898. William had less to do with the family business—he lived in Boston a while, then Maynard again, then off to Pasadena, California, in 1885 for reasons of ill health (possibly tuberculosis). He recovered and moved back east to Worcester in 1888 for the remainder of his life. Harlan died at age 18.[11][13]

Lorenzo married Lucy Davidson and had five children, but all of them died without issue—the four daughters passing away before their parents. William married Mary Adams and had seven children. Descendants of two—Harlan James and Lessie Louise—are alive today, but not living locally. William's granddaughter, Mary Augusta Sanderson, who died in 1947, was the last descendant to live in Maynard.[11][13]

The Maynard Crypt is a prominent feature on the north side of Glenwood Cemetery, within sight of passers-by on Route 27. It is an imposing earth-covered mound with a granite facade facing the road. The mound is 90 feet (27 m) across and about 12 feet (4 m) tall. The stonework facade is approximately 30 feet (9 m) across. The ceiling of the crypt has a glass skylight surmounted by an exterior cone of iron grillwork. The granite lintel above the door reads "MAYNARD." Chiseled above the lintel are the year 1880 and the Greek letters Alpha and Omega entwined with a Fleur-de-lis Cross. Amory Maynard, his wife, Mary, and twenty-one of their descendants or spouses thereof are interred in the crypt. At one point in time Amory's first son, Lorenzo, along with Lorenzo's wife and their four daughters, were also in the crypt, but in October 1904 Lorenzo's son arranged to have his six family members moved to a newly constructed mausoleum in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Lorenzo had contracted for the mausoleum while still alive but died before it was completed. William, Amory's second son, was buried in the Hope Cemetery, Worcester, along with his wife and four of their seven children.[13]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, Maynard has a total area of 5.4 square miles (13.9 km2), of which 5.2 square miles (13.6 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km2), or 2.42%, is water. Average elevation is roughly 200 feet (~61 m) above sea level; the highest point is Summer Hill, elevation 358 feet (109.1 m); the lowest is the Maynard/Acton border next to the Assabet River, at 145 feet (44.2 m).

The Assabet River flows through Maynard from west to east, spanned by seven road bridges and one foot bridge. The river's vertical drop from the Stow border to the Acton border is 30 feet (9 m). Initially, this was sufficient to hydropower the wool and paper mills, but both later added coal-powered steam engines. Average flow in the river is 200 cubic feet per second (5.7 m3/s). However, in summer months the average drops to under 100 cubic feet per second (2.8 m3/s), in drought conditions as low as 10 cubic feet per second (0.28 m3/s) The flood of March 2010 reached 2,500 cubic feet per second (71 m3/s). Recent, monthly and annual riverflow data is available from the U.S. Geological Service.[17]

Average precipitation, long-term, is 43 inches (1,092 mm) per year, which includes 44 inches (112 cm) of snow. (The snow-to-water conversion is roughly eight inches of snow melts to one inch of water.) However, there has been a trend over the past 100 years of increasing precipitation, so the more recent average is closer to 50 inches per year (127 cm/year), and six of the snowiest winters on record have been since 1992–93.

Maynard borders the towns of Acton, Sudbury and Stow. The town owns water rights to White Pond, located about three miles south of Maynard, in Stow and Hudson.[18]

Transportation

editThe nearest rail station is in South Acton on the MBTA Commuter Rail Fitchburg Line, which is 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Maynard town line. The express commuter rail is approximately 30 minutes to Porter Square in Cambridge and 45 minutes to North Station in Boston. By driving, the connection to Route 2 is 4 miles (6 km) from downtown Maynard. Connections to I-95 in the east and I-495 in the west are both 8 miles (13 km) from downtown Maynard.

Construction of a 3.4-mile (5.5 km) portion of the Assabet River Rail Trail was completed in September 2018. It runs from the South Acton train station at the north end, though the center of Maynard and along the Assabet River to the Maynard:Stow border, where, via White Pond Road, there is access to the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge. ARRT is open to pedestrians and non-motorized transportation (skateboards, bicycles, rollerblades, etc.).[3]

Demographics (2010 and 2020 data)

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,291 | — |

| 1890 | 2,700 | +17.9% |

| 1900 | 3,142 | +16.4% |

| 1910 | 6,390 | +103.4% |

| 1920 | 7,086 | +10.9% |

| 1930 | 7,156 | +1.0% |

| 1940 | 6,812 | −4.8% |

| 1950 | 6,978 | +2.4% |

| 1960 | 7,695 | +10.3% |

| 1970 | 9,710 | +26.2% |

| 1980 | 9,590 | −1.2% |

| 1990 | 10,325 | +7.7% |

| 2000 | 10,433 | +1.0% |

| 2010 | 10,106 | −3.1% |

| 2020 | 10,746 | +6.3% |

| Source: United States Census records and Population Estimates Program data.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25] | ||

The 2020 census put the population at 10,746 residents, a 6.3% increase from the 10,106 reported for 2010.[19] There were 4,262 households and 2.52 people per household. The population density was 1,938 inhabitants per square mile (748/km2). Agewise, the population was 7.6% under the age of 5 years, 21.6% under the age of 18 years, and 15.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median income for a household in the town was $105,254. The median income per capita was $50,946. Percent of persons in poverty was 3.8%. The racial makeup of the town was 92.4% White, 1.3% Black or African American, 0.0% Native American, 1.7% Asian and 1.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.4% of the population.[19]

From 2010 census results: The average household size was 2.38. For the households, 28.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.4% were married couples living together, 9.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.5% were non-families. 30.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The population distribution was 24.2% under the age of 19, 32.0% from 20 to 44, 30.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41.3 years.[20] By per capita income, Maynard ranked 113 out of 351 Massachusetts towns and cities, at $39,447. The median income for a household in the town was $77,622, and the median income for a family was $104,398. About 5.6% of the population were below the poverty line.[20]

Education

editMaynard has three public schools on adjoining campuses off Route 117. There is also an adult education program. One private school offers a classical Christian education program for grades K through 8.

- Green Meadow School: grades Pre-K through 3; 2015–2016 enrollment: 509 students; building opened for start of 1956–1957 school year; major expansion 1988.[26]

- Fowler School: grades 4 through 8; 2015–2016 enrollment: 427 students; building opened January 2001.[27]

- Maynard High School: grades 9 through 12; 2015–2016 enrollment: 485 students; Building opened for start of 2013–2014 school year.[28]

- Hudson Maynard Adult Learning Center offers free adult literacy classes: English Spoken with Other Languages (ESOL) and GED preparation classes.[29]

- The Imago School teaches grades K through 8; enrollment: 90 students; classical Christian education program; opened in 1980.[30]

Government

editMaynard uses the open town meeting form of town government popular in small to mid-sized Massachusetts towns.[31] Anyone may attend a town meeting, but only registered voters may vote. Before the meeting, a warrant is distributed to households in Maynard and posted on the town's website. Each article in the warrant is debated and voted on separately. A minimum of 75 registered voters is required as a quorum to hold a town meeting and vote on town business. The quorum requirement was reduced from 100 in 2009 because at times, meetings were failing to achieve a quorum. Important budgetary issues approved at a town meeting must be passed by a subsequent ballot vote. Maynard's elected officials are a five-member Board of Selectmen. Each member is elected to a three-year term. Also filled by election are the School Committee, Housing Authority, Maynard Public Library Trustees and a Moderator to preside over the town meetings. Positions filled by appointment include the Town Administrator and other positions. Details of government are in the Maynard Town Charter and Town of Maynard Bylaws.[32]

State and federal government

editIn the Massachusetts General Court, Maynard is represented by Rep. Kate Hogan and Sen. Jamie Eldridge. In the United States Congress, Maynard is represented by Rep. Katherine Clark in the House of Representatives. The state's senior (Class I) member of the United States Senate is Elizabeth Warren. The junior (Class II) senator is Ed Markey.

Places of worship

edit- Baha'i Faith Devotional Meetings.

- First Bible Baptist Church.

- Holy Annunciation Orthodox Church; services started 1915; church built 1916[33]

- Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses; hall built 1967.

- New Hope Fellowship Church of the Nazarene

- St. Bridget Roman Catholic Church; services started 1865 in a church on Main Street; cornerstone for current church laid 1881 and church dedicated September 21, 1884[34]

- St. Mary's Indian Orthodox Church; consecrated 2003; building had been St. Casimir Roman Catholic Church (1928–1999), and before that the power station for the Concord, Maynard and Hudson electric trolley (1901–1923)[35]

- St. Stephen's Knanaya Church; building originally built as Finnish Temperance Society ("Alku") in 1910.

History of former places of worship

edit- Congregation Rodoff Shalom 1921–1980; Acton Street, building status: private residence

- Mission Evangelical Congregational Church 1906–2019; Walnut Street, Services started 1906; church built 1913[36] building status: private residence.

- St. John's Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church 1907–1967; Glendale Street, building status: private residence

- St. Casimir Roman Catholic Church 1928–1999; Parish established 1912, holding services at St. Bridget until moving to own building in 1928, building status: St. Mary's Indian Orthodox Church since 2003

- St. George's Episcopal Church 1895–2006; Summer Street, building status: two private residences

- United Methodist Church of Maynard 1895–2014; Main Street, Parish established 1867, church built 1895, closed May 2014, building status: empty

- Union Congregational Church 1852–2017; Main Street. Church built 1853, closed June 2017, building status: privately owned, rented for events, named "The Sanctuary"

Sites of interest

edit- Acme Theater Productions: Established in 1992. Acme is a non-profit community theater company. Its tenancy in the ArtSpace building ended December 31, 2023, with the future undetermined.[37]

- Fine Arts Theatre Place: Established in 1949 by Burton Coughlan, on land that had been a horse stable and livery (later an auto repair shop) started by his father in 1897. Restored in 2007. Three screens. Shows first run movies and classics.[38]

- Glenwood Cemetery: Established in 1871. Of the approximately 7,000 burials, about two dozen pre-date the official creation of the cemetery. Contains the Maynard family crypt. The Town of Maynard has a self-guided walking tour of the cemetery.[39]

- Maynard Public Library, Established in 1881. Was located in building next to Town Hall 1962–2006. Moved to current location at 77 Nason Street in 2006.[40]

- Presidential district/New Village: A housing project for mill workers built 1902–1903 for employees of the American Woolen Company.[41] The American Woolen Company (owner/operator of the mill) initially built 206 houses for workers, on new streets on the south side of town, on farmland purchased from the Reardon and Mahoney families. Added 50 more dwellings in 1918. The district later came to be referred to as the Presidential district because the streets were named after eight post-Civil War Presidents: Arthur, Cleveland, Garfield, Grant, Harrison, Hayes, McKinley and Roosevelt. These were all originally rented housing, but in August 1934 the woolen mill put 101 houses and 49 two-family dwellings up for auction.[42]

Recreation

edit- Alumni Field: provides tennis courts and a 400-meter all-weather rubberized track around the perimeter of the football field. Open to the public. The parcel of land had been the town's Poor Farm. The field was in place for the 1928 high school football season. From 1931 to 1935 the federal New Deal agencies Civil Works Administration (CWA), Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) built the field house, bleachers, tennis courts, running track and a hockey rink.[43]

- Assabet River Rail Trail: Maynard section paved 2017. As planned, the entire trail will follow the 12.4-mile (20 km) route of the South Acton-to-Marlborough railroad line, which had been an active railroad from the 1850s to 1960s.[3] The Maynard section is 2.3 miles (3.7 km) long, from the Acton border in the north to the Stow border in the south. The Trail continues in Acton another 1.1 miles (1.8 km) to the South Acton train station. At the south end there is access to the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge. There is no trail connection to the southern part in Hudson and Marlborough that was completed ~2005.[3] Starting in the fall of 2018, a project named "Trail of Flowers" was initiated with the goal of planting thousands of blooming bulbs plus perennial flowering plants, bushes and trees along the trail. The cost of plants is paid for by donations and the plantings conducted by volunteers.[44]

- Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge: Established in 2000 but not opened to the public until 2005. In 1942 during World War II the U.S. Army had seized land in Maynard, Hudson, Stow and Sudbury from private owners and operated a munitions transportation complex. After the war the land was designated as the Fort Devens-Sudbury Training Annex associated with Natick Laboratories into the 1980s, then a Superfund clean-up site from 1990 to 2000, prior to the creation of the Refuge. The Refuge, 2,230-acre (9.0 km2), offers hunting, fishing and 15 miles (24 km) of trails, half of which are open to bicycling. No motorized vehicles, no boating on the ponds, no fires, no camping, no dogs, no horses.[45] The Friends of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge is a non-profit organization of dedicated and conservation-minded volunteers who work to protect and enhance the refuge's flora and fauna.[14]

- Boating and fishing: The Assabet River upstream from the Ben Smith Dam offers miles of still water for fishing, canoeing and kayaking. There is a kayak/canoe launch dock at Ice House Landing, Winter Street, and an area at White Pond Road suitable to put boats into the water. This part of the river has a warm water, Class B, "fishable and swimmable" water quality classification.[46] The mill pond adjacent to Main Street is the property of Mill & Main Place, owners of the mill building complex. Inflow is from the Assabet River and outflow same. Both are controlled by Mill & Main Place. Fishing is allowed but no swimming, boating or ice skating.

- Crowe Park: Baseball and recreational field on Route 117. The park was named John A. Crowe Park in 1915. Six acres of land had been purchased by the town in 1901. Reverend Crowe was pastor of St. Bridget's Church 1895–1905. He was responsible in getting the town to buy the land, and was the first superintendent of the park.[11]

- Maynard Dog Park: Located at the southwest edge of the Maynard solar field on Waltham Street. It is open to residents of Maynard and the surrounding area, free of charge, and provides a fenced area where dogs can be off the leash.[47]

- Hiking trails and open spaces: The Maynard Conservation Commission provides on-line maps of the town's open spaces and public trails, including on Summer Hill.[48]

- Historic Walking Tours: The Town of Maynard has established six self-guided walking tours of Maynard. PDFs can be downloaded from the town's website.[39]

- Maynard Golf Course: Nine hole golf course, 2,601 to 3,013 yards depending on choice of tees, established in 1921 as Maynard Country Club. Purchased by Town of Maynard in 2012. Managed by Sterling Golf Management, Inc.[49] The former country club building is the headquarters for the Maynard Senior Center,[50] a service of the Maynard Council on Aging.

- Maynard Rod and Gun Club: Had its beginnings as Maynard Gun Club in 1902. Moved to current location off Old Mill Road in 1946. Owns 93 acres in Maynard and Sudbury. Offers two lighted skeet fields, two trap ranges, a 100-yard outdoor rifle range, one outdoor pistol range, an indoor pistol range, archery range, fishing pond, sports fields and a function hall.[51]

Notable people

edit- Julie Berry, author of ten children's and young adults books; currently living in California

- Luke Brooks (1731–1817) Revolutionary War minuteman at the Battle of Lexington

- Elizabeth Updike Cobblah, artist, daughter of John Updike

- John "Red" Flaherty (1917–1999), born in Maynard, American League baseball umpire 1953–1973

- Michael Goulian, airshow performer and RedBull Air Race pilot

- Herb Greene, noted photographer of the Grateful Dead, moved to Maynard in 1999

- Waino Kauppi, child prodigy cornet player who later went on to be featured with several New York bands

- Amory Maynard (1804–1890), started woolen mill in 1846; alive when Assabet Village became Town of Maynard

- Leo Mullin, CEO of Delta Airlines (1997–2003), born and grew up in Maynard

- Frank Murray (1885–1951), born in Maynard, college football coach Marquette University and University of Virginia; College Football Hall of Fame

- Ken Olsen (1926–2011), founder and president of Digital Equipment Corporation (1957-92); worked in but did not live in Maynard

- Hermon Hosmer Scott (1909–1975), was founder of H.H. Scott, Inc., a Hi-fi company located in Maynard from 1957–1975

- Jarrod Shoemaker, professional triathlete; currently living in Florida

- Tantamous (Old Jethro), (c. 1580–1676), Native American leader in colonial Massachusetts; forced by colonial court to surrender land that later became part of Maynard, executed during King Philip's War

- William G. Tapply (1940–2009), born in Waltham, Massachusetts, lived in Maynard, author of fiction and non-fiction books

Cultural events

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Maynard town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Refuge website: About the Refuge". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- ^ a b c d "Assabet River Rail Trail". Assabet River Rail Trail. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "maps.google.com". Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Hurd, Duane Hamilton (1890). History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men. J. W. Lewis & Company.

- ^ a b c d Gutteridge, William H. (1921). "A Brief History of the Town of Maynard, Massachusetts". pp. 12–16. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Alfred Sereno Hudson, The Annals of Sudbury, Wayland, and Maynard, Middlesex County, Massachusetts (1891), p. 70 (accessible on Google Books)

- ^ Crowell, PR (1933). "Stow, Massachusetts 1683–1933" (PDF). Town of Stow, Massachusetts. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ "Thoreau's walk to Boon's Pond (pages 452–462)" (PDF). The Walden Woods Project. 1851. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Old Marlborough Road, by Henry David Thoreau (1861)". Monadnock Valley Press. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Sheridan, Ralph (1971). A History of Maynard 1871–1971. Town of Maynard Historical Committee.

- ^ Fuller, Ralph. (2009). Stow Things. Stow Historical Publishing Company.

- ^ a b c d e f Mark, David A. (2014). Hidden History of Maynard. The History Press. ISBN 978-1626195417.

- ^ a b "Friends of the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge". www.farnwr.org. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Earls, Alan R. (2004). Digital Equipment Corporation. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3587-6

- ^ a b "Maynard Farmers' Market". Maynard Farmers' Market. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ USGS Current Conditions for USGS 01097000 ASSABET RIVER AT MAYNARD, MA. Waterdata.usgs.gov. Retrieved on July 17, 2013.

- ^ Stantec Consulting Services Inc. (July 31, 2019). "Maynard White Pond Treatment and Transmission Study" (PDF). Town of Maynard, MA. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Maynard CPD, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau. 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Census website". Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21–10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21–5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Green Meadow School. Retrieved on November 5, 2017

- ^ Fowler School. Retrieved on November 5, 2017

- ^ "Maynard High School". Maynard High School. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Hudson Maynard Adult Learning Center. Retrieved on November 5, 2017

- ^ "The Imago School". The Imago School. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Town Meetings | Maynard, MA". www.townofmaynard-ma.gov. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ "Charter and Bylaws". Town of Maynard, Massachusetts. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "Holy Annunciation Orthodox Church". Holy Annunciation Orthodox Church. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Saint Bridget Parish". Saint Bridget Parish. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "St. Mary's Indian Orthodox Church of Boston". St. Mary's Indian Orthodox Church of Boston. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Mission Evangelical Congregational Church". Mission Evangelical Congregational Church. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Acme Theater Productions

- ^ Fine Arts Theater

- ^ a b Historic Walking Tours of Maynard

- ^ "Maynard Public Library". Maynard Public Library. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Beginning of New Village" Maynard Historical Society Archives

- ^ "NOTIFICATION OF PUBLIC AUCTION OF ASSABET MILLS PROPERTIES" Maynard Historical Society Archives

- ^ The Living New Deal

- ^ "Trail of Flowers". Trail of Flowers. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "About the Refuge". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- ^ The Sudbury, Assabet and Concord Wild and Scenic River Stewardship Council

- ^ "MayDOG (Maynard Dog Park)". The Maynard Dog Owners Group. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "Open Spaces and Trails Map". Town of Maynard, Massachusetts. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Maynard Golf Course". Sterling Golf Management, Inc. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "The Maynard Senior Center". Town of Maynard, Massachusetts. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to the Maynard Rod and Gun Club". Maynard Rod and Gun Club, Inc. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Maynard Fest". Assabet Valley Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

Further reading and information

edit- Boothroyd, Paul and Lewis Halprin (1999). Maynard Massachusetts, Images of America. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0074-7

- Boothroyd, Paul and Lewis Halprin (1999). Assabet Mills, Images of America. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0262-6

- Boothroyd, Paul and Lewis Halprin. (2005) Maynard, Postcard History Series. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3946-5

- Brown, Peggy Jo (2005). Hometown Soldiers: Civil War Veterans of Assabet Village and Maynard Massachusetts. Maynard, MA: Flying Heron Press.

- Cummings, O.R. (1967). Concord, Maynard & Hudson Street Railway. Warehouse Point, CN: National Railway Historical Society.

- Earls, Alan R. (2004) Digital Equipment Corporation. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3587-6

- Fuller, Ralph. (2009). Stow Things. Stow Historical Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-9825429-1-0

- Gutteridge, William H. (1921). A Brief History of the Town of Maynard, Massachusetts. Maynard, MA: Town of Maynard. Available at Maynard Historical Society as 19 MB pdf: http://collection.maynardhistory.org/archive/files/maynard-1921-gutteridge-web_5bacc350d3.pdf

- Mark, David A. (2011). Maynard: History and Life Outdoors. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-303-5

- Mark, David A. (2014). Hidden History of Maynard. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62619-541-7

- Mullin, John R. "Development of the Assabet Mills in 19th Century Maynard", Faculty Publication Series, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1992.

- Schein, Edgar H. (2003). DEC is Dead, Long Live DEC. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57675-305-7

- Sheridan, Ralph (1971). A History of Maynard 1871–1971. Town of Maynard Historical Committee. Available at Maynard Historic Society as a 95 MB pdf: http://collection.maynardhistory.org/archive/files/maynard-1871-1971-web_4226f59f9f.pdf

- Town of Maynard (2020). Maynard Massachusetts: a Brief History. Town of Maynard Sesquicentennial Steering Committee. Charles ton, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-46714-474-2

- Voogd, Jan (2007). Maynard Massachusetts, A House in the Village. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-205-5