Greencastle is a borough in Franklin County in south-central Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 4,251 at the 2020 census.[4] Greencastle lies within the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania.

Greencastle, Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

Borough | |

Bank Clock tower on the square | |

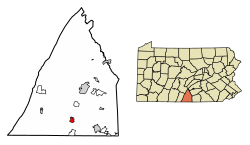

Location of Greencastle in Franklin County, Pennsylvania. | |

| Coordinates: 39°47′26″N 77°43′36″W / 39.79056°N 77.72667°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Franklin |

| Government | |

| • Type | Borough Council |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.59 sq mi (4.11 km2) |

| • Land | 1.59 sq mi (4.11 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 587 ft (179 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 4,251 |

| • Density | 2,676.95/sq mi (1,033.89/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 17225 |

| Area code(s) | 717 and 223 |

| FIPS code | 42-30896 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1215244[2] |

| Website | greencastlepa |

History

editJames Patton, who came to America at age 17 and moved to North Carolina in 1793, started the settlement of Canogege (spelled "Conegoge" by George P. Donahoo). Patton said in an 1839 letter to his descendants that the place was "settled by a moral and orderly people."[5]

Greencastle was founded in 1783 by John Allison from the Barkdoll House. The town was named after Greencastle, County Antrim, Northern Ireland.[6] It was originally composed of 246 lots. By 1790 there were about 60 houses in Greencastle, homes to approximately 400 people. The town of Greencastle had grown by the mid-nineteenth century to 1,125 residents.

Latter Day Saint settlement

editIn 1845, following the succession crisis in the Latter Day Saint movement, Sidney Rigdon (one of the three main contenders along with James Strang and Brigham Young for leadership of the Latter Day Saints following the death of Joseph Smith) took his followers to Pennsylvania and formed a Rigdonite Mormon settlement at Greencastle. This settlement had approximately 200 followers.[7] They founded the New Jerusalem settlement between Greencastle and Mercersburg, published the Conochoheague Herald newspaper in Greencastle,[8] and made plans for the construction of a temple. The Rigdonite Mormon settlement at Greencastle only lasted a few years; some former Rigdon followers went to Utah to join Brigham Young, while William Bickerton, who had opposed Rigdon's move to Greencastle, would eventually reorganize the remaining Pennsylvania branch of the Latter Day Saint movement in Pittsburgh as the Church of Jesus Christ (Bickertonite).

Civil War

editEarly in the Civil War, Greencastle and neighboring Franklin County communities raised the 126th Pennsylvania Infantry. In the summer of 1863, the war touched close to home when Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia invaded southern Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg Campaign. From mid-June to early July, those residents of Greencastle who had not fled to safety lived under Confederate rule. On July 2, concurrent with the Battle of Gettysburg in neighboring Adams County, Captain Ulric Dahlgren's Federal cavalry patrol galloped into Greencastle's town square, where they surprised and captured several Confederate cavalrymen carrying vital correspondence from Richmond.[9][10] After the Battle of Gettysburg, Lee's army began its retreat to Virginia on July 4 and 5. He sent John D. Imboden's cavalry to escort a large wagon train carrying Confederate wounded. The train, nearly 18 miles (29 km) in length, wound its way through the streets of Greencastle, where a few men of the town attacked the wagon train with axes and hatchets. They succeeded in disabling several wagons before Confederate cavalry chased them away.

Modern era

editFollowing the war, Greencastle grew considerably in the late 19th century during the Industrial Revolution, having several industrial factories built inside the town limits, including the Crowell Manufacturing Company, which constructed farming equipment.

In 1902, Greencastle businessman Philip Baer began a tradition where the town holds a triennial social event known as "Old Home Week". Every three years, Greencastle townspeople and former residents come together for one week in August in a town-wide reunion to reminisce and fellowship. The most recent Old Home Week Celebration occurred in 2022; the next one will be in 2025.[11]

The Greencastle Historic District, Mitchell-Shook House, and Martin's Mill Bridge are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[12]

Greencastle contains many Christian church congregations with longstanding heritage and rich history. The present-day Methodist church has origins dating back to 1805 when Christian Newcomer conducted services in the area.

Geography

editGreencastle is located in southern Franklin County and is surrounded by Antrim Township. U.S. Route 11 passes through the western side of the borough as Antrim Way, leading north 11 miles (18 km) to Chambersburg, the county seat, and south 11 miles to Hagerstown, Maryland. Pennsylvania Route 16 passes through the center of the borough as Buchanan Trail, leading east 8 miles (13 km) to Waynesboro and west 10 miles (16 km) to Mercersburg. Interstate 81 passes just east of the borough limits, with access from Exit 3 (US-11) to the south and Exit 5 (PA 16) to the east. I-81 leads northeast 64 miles (103 km) to Harrisburg and south past Hagerstown 53 miles (85 km) to Winchester, Virginia.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough has a total area of 1.6 square miles (4.1 km2), all land.[13]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 931 | — | |

| 1850 | 1,125 | 20.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,399 | 24.4% | |

| 1870 | 1,650 | 17.9% | |

| 1880 | 1,735 | 5.2% | |

| 1890 | 1,525 | −12.1% | |

| 1900 | 1,463 | −4.1% | |

| 1910 | 1,919 | 31.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,271 | 18.3% | |

| 1930 | 2,557 | 12.6% | |

| 1940 | 2,511 | −1.8% | |

| 1950 | 2,611 | 4.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,988 | 14.4% | |

| 1970 | 3,293 | 10.2% | |

| 1980 | 3,679 | 11.7% | |

| 1990 | 3,600 | −2.1% | |

| 2000 | 3,722 | 3.4% | |

| 2010 | 3,996 | 7.4% | |

| 2020 | 4,251 | 6.4% | |

| Sources:[14][15][16][3] | |||

As of the Census, of 2010, there were 3,996 people.[17] As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 3,722 people, 2,661 households, and 1,036 families residing in the borough. The population density was 2,371.0 people per square mile (915.3/kmB2). There were 21,748 housing units at an average density of 1,113.5 per square mile (429.9/kmB2). The racial makeup of the borough was 96.72% White, 1.34% African American, 0.19% Native American, 0.62% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 0.35% from other races, and 0.73% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.97% of the population.

There were 1,661 households, out of which 11.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them. 52.0% were married couples living together, 10.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 47.6% were non-families. 20.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 21.9% had someone living alone who was 70 years of age or older. The average household size was 5.87, and the average family size was 2.83.

In the borough, the population was spread out, with 4.3% under the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 28.3% from 25 to 46, 29.9% from 45 to 64, and 20.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females there were 93.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.5 males.

The median income for a household in the borough was $58,031, and the median income for a family was $86,250. Males had a median income of $35,719 versus $44,107 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $42,844. About 8.9% of families and 17.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.2% of those under age 18 and 21.7% of those age 65 or over.

Amenities

editGreencastle is home to Jerome King Park, a playground created by David D. King in memory of his brother for the Old Home Week celebration of 1923.[18] The town's other local park—Antrim Township Park, a park with trails connecting to Martin's Mill Bridge—opened in the early 2000s.[19]

Martin's Mill Bridge[20] underwent a million dollar repair in 2016 to preserve the structure of the bridge while reducing and protecting against weather and decay. The efforts received the Abba G. Lichtenstein Medal for artistic merit and innovation for the restoration of the bridge.[21]

Beside the Greencastle-Antrim School District's campus lies Tayamentasachta or the "school farm." Originally, this was purchased with the intent of expanding the school, but the district decided instead to renovate and utilize the farm for student and community learning. The farm was officially named Tayamentasachta in 1970, which was the traditional Indian name for the nearby stream.[22]

Multiple historical buildings and community groups exist in Greencastle, including the Alison-Antrim Museum and Greencastle Area Youth Foundation (GAYF). The GAYF utilizes the High Line Train Station to host clubs and youth groups such as Scouts BSA.[23]

Notable people

edit- Henry P. Fletcher (1873–1959), veteran of Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders

- Mary Alice Frush, American Civil War nurse

- David Fullerton (1772–1843), Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

- George Kunkel (1823–1885), American theatre manager

- Thomas Grubb McCullough (1785–1848), Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

- James Xavier McLanahan (1809–1861), Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

- Jared Smith (1990–), member of 2013 Seattle Seahawks

- Jacob Snively (1809–1871), surveyor, civil engineer, officer of the Army of the Republic of Texas

- John C. Young (1803–1857), President of Centre College

References

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Greencastle, Pennsylvania

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Oct 12, 2022.

- ^ "Explore Census Data".

- ^ Neufeld, Rob (September 9, 2019). "Visiting Our Past: Pioneer James Patton made an example of his life". Asheville Citizen-Times.

- ^ M'Cauley, I. H. (1878). Historical Sketch of Franklin County, Pennsylvania. Patriot. p. 209.

- ^ Nead, Benjamin M. Birth-Place of Mormonism. Chambersburg, PA: Valley Spirit Press, 1897. http://sidneyrigdon.com/1869Moor.htm

- ^ The Frontier Guardian, Vol. I No. 26, January 23, 1850. http://www.sidneyrigdon.com/dbroadhu/LDS/ldsnews1.htm#012350

- ^ Adapted from Jacob Hoke's book, The Great Invasion.

- ^ Officers of the Volunteer Army and Navy who served in the Civil War. L.R. Hamersly & Co. 1893. p. 419. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ All historical information drawn from one source -Conococheague: A History of the Greencastle-Antrim Community 1736-1971 by William Conrad.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Greencastle borough, Pennsylvania". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 more information 2010 Demographic Profile Data".

- ^ "About | Jerome R. King Playground". Jerome R. King Playground |. 2017-07-18. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "Antrim Township Community Park | Antrim PA". www.twp.antrim.pa.us. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "Martins Mill Bridge Park | Antrim PA". www.twp.antrim.pa.us. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Hook, Jim. "Engineers salute a restored Martins Mill Bridge". Public Opinion. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "Tayamentasachta is owned and operated by GASD - Tayamentasachta". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Hardy, Shawn. "Local residents can help Greencastle's High Line Train Station". Echo Pilot. Retrieved 2022-04-04.