Grigory Petrovich Danilevsky (Russian: Григо́рий Петро́вич Даниле́вский; 26 April [O.S. 14 April] 1829 – 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1890) was a Russian historical novelist, and Privy Councillor of Russia. Danilevsky is well known as the author of the novel Beglye v Novorossii (Fugitives in New Russia, 1862).

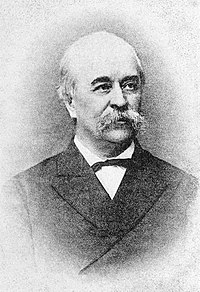

Grigory Danilevsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Grigory Petrovich Danilevsky 26 April 1829 Kharkov Governorate |

| Died | 18 December 1890 (aged 61) St. Petersburg |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Period | 1850s-1880s |

Life

editBorn into the family of an impoverished landowner, Petr Ivanovich Danilevsky, in the Izyumsky district of Kharkov Governorate, Grigory was educated in the Moscow Dvoryansky institut (Institute of the Nobility) from 1841 to 1846, then studied law at Saint Petersburg University. In 1849 he was mistakenly arrested in connection with the Petrashevsky case and spent several months in the prison of the Peter and Paul Fortress, but he was released and received his certification as kandidat in 1850. From 1850 to 1857 he served in the Ministry of Education, where he was sent a number of times to examine the archives of monasteries in the south. In 1856 he was one of the writers sent by Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich to study the borderlands of Russia.

In 1857 he retired to his estates in the Kharkov Governorate, serving in various local offices, but in 1869 he became an assistant editor of the new Pravitelstvenny vestnik (Government Herald) and in 1881 was named the chief editor, thus becoming part of the council supervising the Russian press. He died in December 1890 in Saint Petersburg and was buried in the village of Prishib in the Kharkov (present-day Kharkiv, Ukraine).

Literary career

editAside from some minor verses and translations, Danilevsky's first literary work was a series of stories of Ukrainian life and traditions, collected in 1854 in the book Slobozhane (Sloboda dwellers). His first novel, Beglye v Novorossii (Fugitives in Novorossiya, 1862), published under the pseudonym D. Skavronsky, brought him wide success; it was followed by Beglye vorotilis (The return of the fugitives, 1863) and Novye mesta (New places, 1867), the whole trilogy describing the settlement of the Ukrainian steppe by runaway serfs.[1] His 1868 story "Zhizn cherez sto let" (Life a hundred years from now, 1868) was a work of science fiction imagining the year 1968.

Better known are his novels of the following decades, published in Vestnik Evropy and Russkaya Mysl (Russian Thought). In 1874 appeared Devyaty val (The ninth wave), about the struggle between conservatives and reformers in the 1860s. The following year he wrote Mirovich, which "deals with the tragic fate of the deposed child-emperor Ioann Antonovich and the foiled attempt by Lieutenant Mirovich to free him from Shlisselburg," but it was banned by the censor and did not appear until 1879;[2] Isabel Florence Hapgood called it his best novel, "though it takes unwarrantable liberties with the personages of the epoch depicted."[3] It was followed by Na Indiyu pri Petre (To India in Peter's day, 1880); Knyazhna Tarakanova (Princess Tarakanova, 1883), about the self-proclaimed daughter of Empress Elizabeth; Sozhzhennaya Moskva (Moscow destroyed by fire, 1886), about Napoleon's invasion in 1812; Cherny god (The black year, 1888), about Pugachev's Rebellion; and a series of short stories.

Though Danilevsky was popular in his day, Prince Mirsky says he was "looked down by the advanced and the literate," and calls his novels "derivative and second-rate."[4] However, Dan Ungurianu writes, "Despite their lack of conceptual and artistic integrity, Danilevsky's novels remain among the best works of historical fiction of the period."[5]

English Translations

edit- The Princess Tarakanova, (Novel), Macmillan, NY, 1891. from Archive.org

- Moscow in Flames, (Novel), Stanley Paul, London, 1917. from Archive.org

References

edit- ^ Myroslav Shkandrij, Russia and Ukraine: Literature and the Discourse of Empire from Napoleonic to Postcolonial Times (McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 2001: ISBN 0-7735-2234-4), p. 169.

- ^ Dan Ungurianu, Plotting History: The Russian Historical Novel in the Imperial Age (University of Wisconsin Press, 2007: ISBN 0-299-22500-3), p. 128.

- ^ Isabel Florence Hapgood, A Survey of Russian Literature, with Selections (Chautauqua Press, 1902), p. 230.

- ^ D.S. Mirsky, A History of Russian Literature from Its Beginnings to 1900 (Northwestern University Press, 1999: ISBN 0-8101-1679-0), p. 297.

- ^ Ungurianu, Plotting History, p. 129.

External links

edit- Works by Grigory Danilevsky at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Grigory Petróvich Danilevsky (1829–1890), in: C.D. Warner, et al., comp. The Library of the World’s Best Literature. An Anthology in Thirty Volumes. 1917.