The Guanahatabey (also spelled Guanajatabey) were an Indigenous people of western Cuba at the time of European contact. Archaeological and historical studies suggest the Guanahatabey were archaic hunter-gatherers with a distinct language and culture from their neighbors, the Taíno. They might have been a relict of an earlier culture that spread widely through the Caribbean before the ascendance of the agriculturalist Taíno.

Description

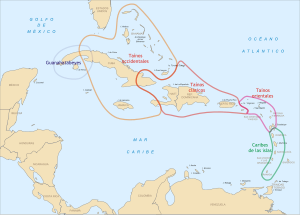

editContemporary historical references, largely corroborated by archaeological findings, placed the Guanahatabey on the western end of Cuba, adjacent to the Taíno living in the rest of Cuba and the rest of the Greater Antilles.[1] The term Guanahatabey is not necessarily the term with which the population identified itself before the arrival of the European colonisers, but likely an adaption based on the limited understanding of the latter, similar to the term Taíno.[2] At the time of European colonisation, they lived in what is now Pinar del Río Province and parts of Habana and Matanzas Provinces.[3] Archaeological surveys of the area reveal an archaic population of hunter-gatherers inhabiting the entire Cuban archipelago. Unlike the neighbouring Taíno, they practiced no larger scale agriculture, but subsisted mostly on small scale horticulture, [4] shellfish and foraging, and supplemented their diet with fish and game. They lacked ceramic pottery, and made stone, shell, and bone tools using grinding and lithic reduction techniques.[1]

The language of the Guanahatabey is lost except for a handful of placenames. However, it appears to have been distinct from the Taíno language, as the Taíno interpreter for Christopher Columbus could not communicate with them.[1]

As similar archaic sites dating back centuries have been found around the Caribbean, archaeologists consider the Guanahatabey to be late survivors of a much earlier culture that existed throughout the islands before the rise of the agricultural Taíno. Similar cultures existed in southern Florida at roughly the same time, though this could simply have been an independent adaptation to a similar environment. Genetic studies of related archaic-period individuals across Cuba have shown affinities to both South and North America.[5] It is possible the Guanahatabey were related to the Taíno, however, there is evidence of a genetic mixture in Haiti.[6]

History

editColumbus visited the Guanahatabey region in April 1494, during his second voyage. The expedition encountered the locals, but their Taíno interpreters could not communicate with them, indicating that they spoke a different language.[7] The first recorded use of the name "Guanahatabey" is in a 1514 letter by the conquistador Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar; Bartolomé de las Casas also referred to them in 1516. Both writers described the Guanahatabey as primitive cave-dwellers who chiefly ate fish. The accounts are second-hand, evidently coming from Taíno informants. As such, scholars such as William F. Keegan cast doubt on these reports as they could reflect Taíno legends about the Guanahatabey rather than reality.[1][8] The Spanish made sporadic references to the Guanahatabey and their distinctive language into the 16th century.[9] They seem to have disappeared before any further information about them was recorded.[1]

Confusion with the Ciboney

editIn the 20th century, misreadings of the historical record led scholars to confuse the Guanahatabey with another Cuban group, the Ciboney. Bartolomé de las Casas referred to the Ciboney, and 20th-century archaeologists began using the name for the culture that produced the archaic-period aceramic sites they found throughout the Caribbean. As many of these sites were found in the former Guanahatabey region of western Cuba, the term "Ciboney" came to be used for the group historically known as the Guanahatabey.[10] However, this appears to be an error; las Casas distinguished between the Guanahatabey and the Ciboney, who were a western Taíno group of central Cuba subject to the eastern chiefs.[10]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e Rouse, pp. 20–21.

- ^ A. Curet 2014 "The Taino: Phenomena, Concepts, and Terms"

- ^ Granberry and Vescelius, p. 15, 18–19.

- ^ Chinique de Armas et al. 2016 "Starch analysis and isotopic evidence of consumption of cultigens among fisher–gatherers in Cuba: the archaeological site of Canímar Abajo, Matanzas"

- ^ Nägele et al. 2020 "Genomic insights into the early peopling of the Caribbean" Science

- ^ Fernandes et al. "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean"

- ^ Rouse, p. 20, 147–148.

- ^ Saunders, p. 122.

- ^ Granberry and Vescelius, p. 19.

- ^ a b Saunders, p. 123.

References

edit- Granberry, Julian; Vescelius, Gary (1992). Languages of the Pre-Columbian Antilles. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 081735123X.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Saunders, Nicholas J. (2005). The Peoples of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archeology and Traditional Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576077012. Retrieved June 23, 2014.