Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion (Finnish: Henkikaartin 3. Suomen Tarkk’ampujapataljoona, Swedish: Livgardets 3:e finska skarpskyttebataljon, Russian: Лейб-гвардии 3-й стрелковый Финский батальон, romanized: Leib-gvardii 3-j strelkovyi Finski bataljon), colloquially known as just Finnish Guards (Finnish: Suomen kaarti, Swedish: Finska gardet) was a Finnish military unit during 1829–1905 based in Helsinki. Continuing the legacy of the Finnish Training Battalion (1817), it was part of the Imperial Russian Army and the only Finnish unit of the Russian Imperial Guard. For the most of its history, the battalion also functioned as the only operational Finnish military unit. Because of its status as both a national showpiece and as a part of the Imperial Guard, it had a visible role in Finland.

| Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion | |

|---|---|

| Henkikaartin 3. Suomen Tarkk’ampujapataljoona | |

| |

| Active | 1829–1905 |

| Country | Russian Empire |

| Size | 400–600 |

| March | Suomi-marssi |

| Engagements | November Uprising Hungarian Revolution of 1848 Crimean War Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) |

The Finnish Guards' Battalion participated in four campaigns outside Finland. Two of these included actual combat: first in 1831 during the Polish November Uprising and for the second time, on the Balkan front of the Russo-Turkish War. The most famous of the battles it participated in was the battle of Gorni Dubnik in 1877. The unit was also deployed in 1849 to assist in quelling the Hungarian Uprising and later during the Crimean War to guard the western border of Russia. However, it did not engage in combat during these deployments. During peace time, the battalion was responsible for guard duty in Helsinki and participated in the Russian military exercises held annually in Krasnoye Selo.[1]

The neighbourhood of Kaartinkaupunki in Helsinki has been named after the battalion, as it is where the Guards' Barracks (Finnish: Kaartin kasarmi) was based in. The modern Guard Jaeger Regiment considers the Finnish Guard as a part of its official lineage.[2]

Early history

editThe military of the Grand Duchy of Finland was established by an imperial order on 18 September 1812 by Alexander I of Russia, which became the anniversary of the battalion. As per the imperial order, Finland had to form three rifle units, consisting each of two battalions of 600 men, totaling 3600 men. The Governor-General of Finland Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt and many other officials in Finland found it important that in addition to the Russian troops stationed in Finland there was also a domestic military force to respond to any possible future uncertainties. These units were formed of willing recruits as well as pressed vagabonds. The intention was to use these units only within Finnish territory and in defense of the coastline of the Baltic Sea, not for conflicts outside of Finnish borders. The units were to be financed by crowd-sourcing, but the collected funds did not come close to matching the need. Finally it was decided that the Russian state was to bear the capital cost of weapons and other military hardware, while the Senate of Finland bore the maintenance costs. Soldiers were paid 60 Russian rubles for their entire 6 year military contract, as well as one and a half barrels of rye annually.[3]

The first of these three regiments to begin operations was the 3rd regiment, also known as the Viborg regiment. Its first assignment was to undertake guard duties in Saint Petersburg between 31 March 1813 and 31 August 1814, while the majority of the Russian Army was tied in Western and Central Europe in the battles against Napoleon.[4] By the summer of 1813, two other regiments had also been formed; the first consisting of the battalions in Turku and Hämeenlinna and the second of battalions in Heinola and Kuopio. This military force consisting of a few thousand men, however, had little significance to Finnish defense. The force suffered from a lack of artillery, cavalry and technical branches. Furthermore, only the unit in Vyborg was in service continuously, as the enlisted personnel of the other regiments only gathered once per year for a four week military exercise, in addition to the officers who gathered for meetings in the six weeks prior to these exercises.[5] Two of the regiments were changed to regular infantry regiments, while the third held its designation as a rifle regiment.[6]

In the autumn of 1817, the Vyborg regiment was split into two battalions, one of which was moved to Vasa. A part of this new battalion was further separated into a special command of 274 men, left to Hämeenlinna under the command of staff captain Nils Gylling. This became the basis for the Finnish Training Battalion and started operations in the summer of 1818. The battalion was assigned to Helsinki and named The Battalion of Helsinki. The first command was assigned to lieutenant colonel Herman Wärnhjelm. Because there were no suitable preexisting facilities in Helsinki at the time, the battalion remained for training in Hämeenlinna until the Kaartin kasarmi building, designed by Carl Ludvig Engel, was completed in 1822 and the Training Battalion moved in on 23 December 1824.[7] The name of the battalion was changed to the Helsinki Training Battalion in 1819 and then to the Finnish Training Battalion in 1824.[6]

The Finnish military force was re-organised into six rifle battalions by an imperial order in March 1827. The Helsinki Battalion was renamed to the Finnish Training Rifle Battalion and its size was increased from 400 men to 500. Within two months of this change, recruitment for the other Finnish units was ceased and they were ultimately disbanded in 1830. After this, the Helsinki Battalion was the only remainder of the military force formed in 1812.[8] Until the end of the 1870s, the battalion was manned by volunteer Finns, most of whom were part of the Finnish lower classes.[9]

The establishment of the Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion

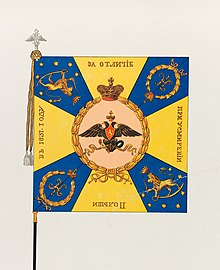

editIn July 1829 the Finnish Training Battalion was suddenly ordered to join the imperial life-guards' exercise camp in Krasnoye Selo, south-west of Saint Petersburg. After inspecting the battalion, Nicholas I of Russia announced that it would be promoted to the rank of Young Guard. In the order of the day for the following day, the name of the battalion was given as "Finnish life-guards' rifle battalion" and it was attached to the 4th brigade, 2nd infantry division of the imperial life guards. Anders Edvard Ramsay continued as the battalion commander. Although the battalion was now a part of the imperial life-guard and under the jurisdiction of its inspector, it also fell under the command of the Governor-General of Finland, who commanded all of the forces located in Finland. The costs of the Finnish Rifle Battalion were still paid from the accounts of the Senate of Finland. Along with the new name and rank, the battalion received new uniforms and a colour, which was consecrated and presented to the battalion on 17 September 1829.[10]

As the battalion gained a higher standing, its strength was also increased to 600 guardsmen. At the same time, it was specified that only men taller than 5 feet and 6,5-inches (168 cm) could be recruited. The Helsinki Training Battalion had only had two permanent officers; a commander and his adjutant, and any other officers were temporarily assigned on secondment from other units of the army. With its promotion to a guard unit, the battalion received 17 permanent officers. Furthermore, the battalion still had to accept all the qualified Finnish noblemen willing to enter military service as non-commissioned officers, as long as they could pay their own living costs until a vacancy for a commissioned officer opened up and they were promoted to commissioned officers. As a result, the battalion became a career shortcut for young noblemen wanting to become officers.[11] In 1829, the command language of the battalion was changed to Russian, replacing the former Swedish. However, the orders of the day and correspondence were still nonetheless written in Swedish for the battalions entire operational history. Additionally, during the last years of the unit, a parallel diary was also kept in Finnish language.[12]

In Russia, the Guard referred to the guard of the sovereign, the Russian Emperor. For this reason, the Finnish Rifle Battalion also participated in public duties in Saint Petersburg, including those pertaining to the protection of the Emperor as the commander in chief of the army and navy. Just like elsewhere in the world, the Russian guard regiments held a clearly more esteemed social position in comparison to regular line infantry. As a result, the units of the Guard enjoyed special privileges; the members of the Imperial family served as honorary commanders of guards' units and officers assigned from the Guard to the normal line-regiments received an automatic promotion to the next rank. In Finland, the guard battalion received special appreciation from the public because it represented Finland's part in the defense of the Russian Empire.

The Polish Uprising 1831

editThe first combat deployment of the battalion was to the campaign to defeat the Polish November Uprising in 1831. In Finland, the mobilization of the battalion was met in the press and within the battalion with positivity and pride. Sending Finnish forces outside of the borders, or taking part to crush the Polish Uprising was no cause of scruples for Finns. The battalion left Finland on the 12 of January with a force of 746 men, marching by foot to Saint Petersburg and, in March, all the way to Poland. The battalion received its baptism of fire in the beginning of the April, together with other imperial forces and Finnish soldiers quickly got a reputation as good marksmen. The mission of the battalion was to evict Polish forces from the area between the Bug and Narew rivers, at the same time as the main Russian Forces were fighting in the south. During May the battalion had to execute a fighting retreat as a result of the effective Polish counter offensive, all the way to Białystok. After that, it joined the Russian Army in Ostrołęka, which marched the long way from the west in order to cross over the Vistula and to attack Warsaw from the west. From 6 to 8 September 1831 the guards riflemen joined the Imperial forces that took Warsaw.[13]

The battalion spent the winter of 1831–32 in Biržai in Latvia, before returning to Helsinki. They lost only ten men in combat, including one officer. However, as many as 399 men died due to illnesses and epidemics on the front. After the November Uprising, on 18 December 1831, Russian Emperor Nicholas I presented the battalion with the Saint George's Guards Colour with the honorific "In honour of the defeating the Polish uprising in 1831" surrounding the emblem of the battalion in honor of the services rendered in the campaign. The same flag was in use until its disbandment.

During times of peace

editThe battalion was from its inception in a visible position in the Grand Duchy of Finland as it was based in the center of the capital city of Helsinki. With time, it became a national symbol, despite its small size, as it highlighted the special status Finland enjoyed within the Russian Empire. The battalion participated in state ceremonies and from 1863 onwards, one of its companies was always present during the opening ceremony of parliament. During the 19th century, the numerous Russian and Finnish troops based in Helsinki and their frequent parades gave the capital quite a militaristic tone, with various incidents caused by the soldiers becoming a part of the normal life of the city. The Finnish Guards' Rifle battalion had responsibility for general guard in Helsinki every Saturday.

The battalion first had its shooting practice with the Russian Army on the Kamppi field (today Narinkkatori), before it got its dedicated shooting range in Punavuori near the current Tehtaanpuisto, where the Russian Embassy is located today. With the development of more powerful rifles, bullets were no longer stopped by the walls of the Punavuori shooting range, but flew out to the sea, causing a danger to marine traffic. Thus, in 1865, the battalion got a new gallery in Taivallahti and ten years later in Pasila.[14]

The younger grandson of Nicholas I of Russia, who later became Alexander III of Russia, was appointed as honorary commander of the battalion as a 3 month old baby, in 1845. It was a remarkable tribute to the battalion and its first company was named "The company of His Majesty" in gratitude. Prince Alexander (later Alexander II of Russia) was also listed in the rolls of the battalion in 1848, just as his older son Nicholas in 1850, prince Nicholas (later Nicholas II of Russia) at the time of his birth 1868 and his son Aleksey in 1904. Alexander III held the position of honorary commander until his death, after which Nicholas II took over the position.[15] The first commander of the battalion Anders Edvard Ramsay received an appointment as the second honorary commander in 1868, sharing this honour with the tsarevich.[16] The battalion was considered to enjoy a special relationship of trust with the Russian Emperor, and when the Emperor visited Helsinki, he and the male members of his family usually wore the uniform of the battalion.[17] After the Emperor died, the uniforms were handed over to the battalion, which stored and preserved them as valuable relics, placed on display in showcase, inside a dedicated church-hall in the Guards' Barracks.[18]

During times of peace, the annual highlight of the battalion was their participation in war games in Krasnoye Selo. The Emperor oversaw the exercises in person. At most there were some 80000 men participating in the 10-week spectacle. During the reign of Nicholas I of Russia, the battalion stopped on its way to Krasnoye Selo in Peterhof for a couple of days to serve as guards and to entertain the Emperor with parades. According to tradition, Nicholas I and his family were always eagerly awaiting the arrival of the Finns. After the war games, the emperor inspected the battalion once again and recognized each soldier with one ruble, one pound of meat and a sip of spirit. Later the meat was replaced with herring. The tradition to serve a herring and a drink to the men was abolished during the reign of Alexander III of Russia.[19]

Between 1837–1846, the battalion annually sent one of its officers to the Caucasus, where the Russian Army was waging a semi-permanent counter-insurgency campaign. The size of the battalion was increased in 1840, after which the Guards' Barracks had to be expanded with an annex building on the side of Kasarmikatu.[20] After the Crimean War, the Russian Army faced budget cuts and the size of the battalion was decreased in early 1860. The Finnish grenadier battalion formed in 1846 was also disbanded in the same year. After the allotment system, which had been reintroduced during the Crimean War, was ramped down in 1867 in response to the famine of 1866–67, the battalion was left as the only operational Finnish military unit.[21] The organization of the Russian military was reformed in 1871 and all rifle battalions were formed into a single rifle brigade, which the Finnish Rifle Battalion was also attached to. At the same time, its name was changed to "The 3rd Finnish life guard rifle battalion".[22][6]

Hungarian Uprising 1849 and Crimean War 1854–56

editAs Nicholas I sent 120,000 men to quell the Hungarian Uprising, the Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion was again deployed. It left Helsinki on 31 May sailing to Latvian Dünamünde (today Daugavgrīva). After spending June and July in Riga, it arrived in Brest on the 8 of August. It did not get closer to Hungary, before Hungarian forces were defeated and the campaign ended. The Finnish Battalion returned home on the 17 of October. Thou the battalion did not engage in combat, they suffered from dysentery during the trip.[23]

The next deployment was during the Crimean War. This time there was a fear that the war could reach Finland and Helsinki itself, but regardless the battalion was commanded to head to Saint Petersburg on 18 of March 1854. It stayed there until the spring and took part in guard duty at the palace, which was considered to be a dignified honorary mission. During September–October the battalion moved to Latvia and in March, to Rakišk from where it was moved in February 1855 to Wilkomir. The bulk of the fighting was in Crimea, but Russia held a large contingent of troops back to secure the western border, in case of an Austrian invasion. Again, the Finnish battalion did not face combat, but still, most of its soldiers died, due to a severe cholera epidemic. During the spring and summer of 1855 the unit was moved around in White Russia, but the cholera epidemic did not cease.[24]

After the loss of Sevastopol in September 1855, the Russian Army anticipated that the coalition could move the troops freed from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea for an offensive against Saint Petersburg, so the Finnish battalion was called home. However, due to the epidemic, it was not allowed into Helsinki, but remained quartered for the following winter and spring in the Karelian Isthmus. During that time, the war ended as Alexander II agreed to peace. After taking part in the crowning of the new Emperor in Moscow, the Finnish battalion finally returned to Helsinki on 29 September 1856. Despite not fighting a single battle, the battalion was recorded to have lost 654 men, however the true figure may be even higher.[25]

Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78

editThe most famous action of the battalion was their participation in the Turkish War in Bulgaria 1877–78. They were deployed with numerous other units in autumn 1877, as the Russian offensive had been stalled due to failed attempts to take the fortress of Plevna. Some of the battalion's men had during the beginning of the war already served in the life-guard of Alexander II. The Finnish battalion was mobilised on the 3 of August 1877, and its size was increased by 200 men. As the battalion left Helsinki on 6 September, it included 719 marksmen, 72 non-commissioned officers, 54 musicians, 21 officers and a few military civil servants. The participation of the battalion in the war was yet again seen as a source of national pride. As it left Helsinki, a large farewell party was held in which the upper classes of the capital took part. The battalion was sent by rail to Frătești in Romania, from where it marched on foot across the Danube in Zimnicea on the 3 of October, reaching Bulgaria.[26]

The Guards' Rifle Brigade was commanded by major general Alexander Ellis and, consequently, the Finnish Guard's Rifle battalion belonged throughout the war in the army commanded by Lieutenant General Joseph Vladimirovich Gourko. Gourko's operations were successful, but they often caused significant casualties. In October, Gourko's task was to siege Plevna from the west by taking over the Turkish positions on the highway to Sofia. The first was the stronghold of Gorni Dubnik. The victorious Battle of Gorni Dubnik on the 24 of October was the first battle in decades to involve the Finnish battalion, and became its most renowned one. Finns belonged to the unit which conducted an offensive against the main redoubt of the fortress. In this battle, the battalion lost 22 men and 95 wounded, including 8 officers, 5 non-commissioned officers and five bandsmen. Two of the wounded died soon after the battle. In total some 3,300 Russians died in the operation.[27][28]

After the battle of Gorni Dubnik, the battalion commander Georg Edvard Ramsay was transferred to command the Semyonovsky Regiment, and he was replaced with colonel Victor Napoleon Procopé. Procopé could not take command until January 1878, so lieutenant colonel Julius Sundman commanded the battalion in the meantime. In November, Gurko's army proceeded towards Sofia. After the capture of Plevna in December, Gourko decided to take his troops across the Balkan Mountains in the middle of the winter as a detour to avoid the heavily defended Arabakonak pass. Due to insufficient resources, crossing the mountains became difficult. The battalion was at the time attached to a unit commanded by general major Dmitry Filosofov, but after crossing the mountain, it was moved back to Ellis's Guards' Brigade. The battalion took part in the peaceful takeover of Sofia on January 5 and in the invasion of Philippopolis between 15–17 January. This came to be its last battle. The battle of Philippopolis was, in fact, larger than that of Gorni Dubnik, but the Guard of Finland only suffered four wounded casualties. Thus, it never became as legendary an event in the battalion's history as the battle of Gorni Dubnik.

On its way towards Adrianople, the battalion bore witness to the tragedy of the Harmanli massacre,[citation needed] but the battalion was not directly involved. At the end of the war, the Finnish Battalion marched all the way to San Stefano, just at the gates of Constantinople, where it was also located as the Treaty of San Stefano came into effect. Here, the battalion faced a Typhoid fever epidemic, which continued until their return home. The battalion returned to Helsinki on the 9 of May 1878 to a festive reception. The Finnish battalion lost during the Turkish War 24 men in battles, later an additional six wounded perished. In the epidemics, a total of 158 men, of which 12 were officers, died.[29]

A memorial for the war was erected on the grounds of Guards' Barracks, where the names of the dead were marked. It was enshrined on the annual of Gorni Dubnik battle on 24 October 1881.[30] There are 27 names in the memorial, including some who died later in epidemics.[31] As the Russo-Turkish War was also the war of Bulgarian independence, the Russian troops of that war have enjoyed special appreciation in Bulgaria. In the Bulgarian textbooks, it has traditionally been recognized, that the war effort included Russian, Romanian and also Finnish soldiers. In this way, the memory of the battalion has been preserved in Bulgaria.[32][33] At the battlefield of Gorni Dubnik, there is today the Park Lavrov, where among the war memorials, there is also a memorial of Finnish soldiers and a common grave. Finnish Defence Forces and political establishment still participate in the Bulgarian memorial celebrations of the battle.[28] In Finland, the memorial of the Russo-Turkish war was used in 1956 by president Urho Kekkonen as a location for inspecting the first Finnish peacekeeping troops contingent deployed to Suez and a common Finnish-Bulgarian memorial ceremony is held at the memorial twice a year.[34][35]

Application of compulsory military service

editThe Act of the Diet of Finland instituting conscription was enacted in 1878 and the first intake of conscripts entered service in 1881. The former commander of the Finnish Guard, General Georg Edvard Ramsay, was appointed commander of the military of the Grand Duchy in 1880, and half of the commanders of the newly founded conscript battalions were officers of the Finnish Guard. All the officers in the NCO training battalion were former members of the Guard. The Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion, the Guard, also became a part of the conscription army, and the former voluntary recruitment ended. At an early stage it was planned that the Guards' Battalion be recruited only from the southern Uusimaa Province, but later, it was decided that conscripts could be enlisted from all over the Grand Duchy in order to maintain the strength of the unit. It was feared, that otherwise, not enough volunteers would apply, since the annual exercises in Krasnoye Selo made service more demanding than in other units. The Guard was also the only portion of the conscription army which could be sent for missions outside of Finland.[36]

The Finnish Guard took part also in the triannual drills in Lappeenranta which Alexander III came to observe in person twice.[37]

From the end of the 19th century onwards it was intended that the Finnish military be merged with the regular Russian Army. In 1882 the uniforms were reformed to be more in line with the Russian style. The Governor General Nikolai Bobrikov noted, that organizational differences and the Finnish officers' lack of knowledge of the Russian language were issues to be fixed.[38]

Disbandment of the Guards' Battalion

editThe Finnish "conscription army" was abolished by a new conscription law enacted by Nicholas II of Russia in July 1901. According to the new legislation, Finns now had to serve in regular Russian units. This decision reflected a general political bias by the Russian Imperial government against regional autonomy, including the creation of separate military units.

For the moment The Guards' Rifle Battalion and the Finnish Dragoon Regiment (based in Vilmanstrand), continued to exist. However the Finnish Dragoons were disbanded the same year, when its officers resigned as a group, in protest against the way Nikolay Bobrikov had treated its commanding colonel Oskar Teodor Schauman. After this, the Rifle Battalion (of the Guard) survived as the only separate Finnish military unit in existence.[39][6]

Between 1901 and 1902, eight officers from the Rifle Battalion resigned in protest against the conscription law which they considered illegal. Their positions were filled with other officers, and the battalion remained as before. Subsequently, the "draft strikes movement" organised large-scale opposition against Finnish conscripts being obliged to undertake their military service in Russian units. As the last Finnish military unit the Rifle battalion became a target of ever stronger Russian criticism. After the murder of General-Governor Bobrikov, Czarist policy towards Finland became more relaxed, and the future of the Guard of Finland was left open. Finnish public opinion expressed a hope that the battalion might become a volunteer (non-conscript) unit, but the leadership of the Russian army refused the idea.[40] In 1905, Russia decided that the Finnish contribution to the defence of the Russian Empire should become monetary (i.e. take the form of a tax instead of service). After this, separate Finnish military units were seen as redundant. The Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion was accordingly disbanded on 21 November 1905.

As the revolutionary unrest of 1905 was spreading in Russia, the General Governor Ivan Obolensky was afraid that Finns might start a separatist rebellion. On 9 April 1905, the Finnish Guard's Rifle Battalion left Helsinki for the annual Krasnoye Selo exercises for the last time, in an atmosphere of crisis. Ten days later, the disestablishment of the Finnish Military District was announced. With this change, the Finnish Guard should have, according to the authorities, been incorporated in the Rifle Brigade of the Guard.[41] However, Emperor Nicholas II disbanded the battalion on 7 August.[6] Obolensky wanted the unit to be disbanded during the Krasnoye Selo exercises, but the commander of the battalion, Nikolai Mexmontan was able to persuade his superiors to allow the unit to be disbanded in a more respectful manner. The battalion held its last parade in Krasnoye Selo on 9 August, and returned to Finland on 28 August to begin disbanding. Most of the rank and file were discharged between 31 August and 2 September.[41] After this, the battalion consisted only of the regular NCOs, bandsmen and a rump contingent of 37 conscripts.[6] The old and new colours, as well as the uniforms of three late emperors that had been preserved in the church-room of the Guards' Barracks, were sent back to St. Petersburg on 6 September. The final disestablishment of the unit took so much time that the last officers and men were discharged only on 14 March 1906. On that date, colonel Mexmontan gave his last order of the day, noting that the Finnish Guard no longer existed.[41]

After the disestablishment of the Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion, Finland was, for the first time since 1812, without a domestic military. This situation continued until the independence of Finland .[41]

Legacy

editIn 1910, all Guards' Rifle Battalions were raised to regimental strength. At that time, a Russian unit established in 1799 as a garrison battalion of the Guard, which had later operated as a reserve infantry regiment, was given the name of His Majesty's Life Guard's 3rd Rifle Regiment, thus taking the position held formerly by the Finnish Guard's Rifle Battalion. These two units had, however, different lineages and they should not be confused. The 3rd Guards' Rifle Regiment was disbanded in 1918.

After the Finnish independence, a regiment with the name of Finnish White Guard (Finnish: Suomen Valkoinen Kaarti) was established. This regiment was quartered at the old barracks of the Guard of Finland, and considered itself as part of its lineage. The regiment was disbanded after the Winter War in December 1940. After that, the guarding and ceremonial duties in Helsinki were handled by Helsinki Garrison Battalion (Finnish: Helsingin varuskuntapataljoona), which was part of the field army. After the Second World War, the unit was renamed a number of times, until in 1957, it received the name Kaartin pataljoona (Guards' Battalion). At the same time, the unit received the lineage and traditions of the Guard of Finland, including the insignia, anniversary and march of the Guard. In 1996, the Guards' Battalion became a part of Guard Jaeger Regiment, but it retained its old name. Currently, the Guards' Battalion considers itself a successor unit of the Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion, and it counts its history from year 1812.[42][2]

The original barracks of the Finnish Guards' Rifle Battalion now house the Finnish Ministry of Defence and the Finnish Defence Command.[43]

Sources

edit- Åke Backström: Suomen Kaarti Balkanin sotaretkellä 1877–1878 Genos (62) 1991. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in Finnish)

- Suomen Kaartinpataljoonan upseeristo lähdettäessä Venäjän – Turkin sotaan 4.9.1877. Retrieved 2015-12-28 (in Finnish)

- Vääpeli Lemminkäisen päiväkirja Suomen kaartin retkestä Konstantinopolin muurien edustalle vuosina 1877–1878. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in Finnish)

- Ekman, Torsten: Suomen kaarti 1812–1905 (suom. Martti Ahti). Schildts, Helsinki 2006. ISBN 951-50-1534-0. (in Finnish)

- Bäckström, Åke: Full cirkel; Finska Gardets befäl 1829 och 1906. Genos 67 (1996) (in Swedish)

References

edit- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 60, 63.

- ^ a b Historia ja perinteet. Finnish Defence Forces. 2014-07-11. Retrieved 2015-12-28.(in Finnish)

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 23–27.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 27–29.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 35–36.

- ^ a b c d e f Backström 1996.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 37–38, 40, 44.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 50, 68.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 363, 365–367.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 51, 54–56, 69.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 58.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 50–51.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 84, 86–87, 90–91, 94, 98–100, 104–105, 109–111, 116.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 45, 51, 355–357, 368, 388–389.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 135–136.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 248.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 13.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 148–149.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 147, 152, 156.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 136–137.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 70, 220, 241.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 248–249.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 140–143.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 182–183, 187–188, 191, 194–196.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 73, 206–207, 210–211, 220.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 260–264, 270, 278.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 274–275, 284, 290–291.

- ^ a b 130 vuotta Gornyi Dubnjakin taistelusta Suomen suurlähetystö, Sofia 6.11.2007. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 324–327, 330–333, 337–339.

- ^ Gornij Dubnjakin taistelun muistomerkki Archived 12 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Julkiset veistokset -database. Helsingin taidemuseo. Referenced 11.8.2013.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 290.

- ^ Pentti Pekonen: Verisiteet yhdistävät Suomen ja Bulgarian Archived 28 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Bulgarian Viesti 3/2002. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in Finnish)

- ^ Suomen kaarti vakiinnutti Pohjolan suhteet Bulgariaan Turun Sanomat 27.4.2008. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

- ^ Suomen ensimmäiset rauhanturvaajat. Yle. 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in Finnish). The information is in the video, not in the text body.

- ^ Loukola, Pauli. Gornyj Dubnjakin taistelu elää muistissa. Ruotuväki/Finnish Defence Forces. 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in Finnish)

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 245, 378–381.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 380–381

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 389, 396, 402.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 397.

- ^ Ekman 2006, s. 411–412, 416–417.

- ^ a b c d Ekman 2006, s. 418–421.

- ^ Marko Maaluoto: Kaartin pataljoona – kaupungin vahdissa ja hallitsijan joukkona Helsingin Reservin Sanomat 8–9/2013, p. 10-11. Retrieved 2015-12-28. (in Finnish)

- ^ Kaartin kasarmi. Valtakunnallisesti merkittävät rakennetut kulttuuriympäristöt. Finnish Bureau of Antiquities. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-22. (in Finnish)