The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask[a] is a 2000 action-adventure game developed and published by Nintendo for the Nintendo 64. It was the second The Legend of Zelda game to use 3D graphics, following Ocarina of Time (1998). Designed by a creative team led by Eiji Aonuma, Yoshiaki Koizumi, and Shigeru Miyamoto, Majora's Mask was completed in less than two years. It features enhanced graphics and several gameplay changes, but reuses elements and character models from Ocarina of Time, which the game's creators called a creative decision made necessary by time constraints.

| The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask | |

|---|---|

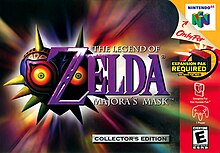

North American box art featuring the titular Majora's mask | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo EAD |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | |

| Producer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Koji Kondo |

| Series | The Legend of Zelda |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The story takes place months after Ocarina of Time. Link arrives in a parallel world, Termina, and becomes embroiled in a quest to prevent the moon from crashing in three days' time. The game introduces gameplay concepts revolving around a perpetually repeating three-day cycle and the use of various masks that transform Link into different forms. As the player progresses through the game, Link learns to play numerous melodies on his ocarina, which allow him to control the flow of time, open hidden passages, or manipulate the environment. Characteristic of the Zelda series, completion of the game involves successfully navigating through several dungeons that contain complex puzzles and enemies. Majora's Mask requires the Expansion Pak add-on for the Nintendo 64, which provides additional memory for more refined graphics and greater capacity in generating on-screen characters.

Majora's Mask earned universal acclaim from critics and is widely considered one of the best video games ever made. It received praise for its level design, story, and surrealist art direction, and has been noted for its darker tone and themes compared to other Nintendo titles.[1] While the game only sold about half as many copies as its predecessor, it generated a substantial cult following.[2][3] The game was rereleased as part of The Legend of Zelda: Collector's Edition for the GameCube in 2003, and for the online services of the Wii, Wii U, and Nintendo Switch. An enhanced remake for the Nintendo 3DS, The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D, was released in 2015.

Gameplay

editThe Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask is an action-adventure game set in a three-dimensional (3D) environment. Players control the on-screen character, Link, from a third-person perspective to explore dungeons, solve puzzles, and fight monsters. Players may direct Link to perform basic actions such as walking, running, and context-based jumping using the analog stick, and must use items to navigate the environment.[4] In addition to wielding a sword, Link can block or reflect attacks with a shield, stun enemies by throwing Deku Nuts, attack from a distance with a bow and arrow, and use bombs to destroy obstacles and damage enemies. He can also latch onto objects or paralyze enemies with the Hookshot. These actions are aided by the "Z-targeting" system introduced in Ocarina of Time, wherein the player may lock the camera onto a particular character, object, or enemy and maintain it in view regardless of Link's motion through the environment.[5]: 15 Similar to other games in the series, Link must progress through a variety of dungeons, which include numerous puzzles that the player must solve.[6] Dungeons also contain optional puzzles that award collectible fairies, which grant Link additional abilities when all are gathered.[5]: 37 As a direct sequel to Ocarina of Time, the first 3D title in the series, the game retains its predecessor's gameplay systems and control scheme while introducing new elements including character transformations and a three-day cycle.[7]

Masks and transformations

editWhereas the masks in Ocarina of Time are limited to an optional sidequest, they play a central role in Majora's Mask, which has twenty-four masks in total.[4] Using the three primary masks, the player can transform Link into different creatures: a Deku Scrub, a Goron, and a Zora.[5]: 24–27 Each form features unique abilities: Deku Link can perform a spin attack, shoot bubbles, skip on water, and fly for a short time by launching from Deku Flowers; Goron Link can roll at high speeds, punch with deadly force, pound the ground with his massive, rock-like body, and walk in lava without taking damage; Zora Link can swim faster, throw boomerang-like fins from his arms, generate an electric force field, and walk on the bottoms of bodies of water. Some areas can only be accessed by use of these abilities.[5]: 24–27 Link and his three transformations receive different reactions from other characters which is key to solving certain puzzles.[5]: 24 For instance, Goron and Zora Link can exit Clock Town at will, but town guards do not permit Deku Link to leave due to his childlike appearance.

Other masks provide situational benefits without transforming Link. For example, the Great Fairy's Mask helps locate stray fairies in the four temples, the Bunny Hood increases Link's movement speed, and the Stone Mask renders Link invisible to most enemies. Certain masks are involved only in sidequests or specialized situations. Examples include the Postman's Hat, which grants Link access to items in mailboxes,[8] and Kafei's Mask, which initiates a long sidequest to locate a missing person.[9]

Three-day cycle

editMajora's Mask revolves around a three-day cycle[5]: 10 (about 54 minutes in real time), in which non-player characters and events follow a predictable schedule.[4] An on-screen clock tracks the day and time. Players may save their game and return to 6:00 am of the first day by playing the Song of Time. Players must use knowledge accumulated from previous cycles to solve puzzles, complete quests, and unlock dungeons related to the main story. Although returning to the first day resets most quests and character interactions, Link retains weapons, equipment, masks, learned songs, and proof of dungeon completion.[5]: 10–11 Link may slow down time by playing the Inverted Song of Time or skip to the next morning or evening using the Song of Double Time. Owl statues scattered across major areas of the world allow players to temporarily save their progress after activation and also provide warp points to quickly navigate the world using the Song of Soaring.[5]: 13, 40

During the three-day cycle, Link tracks characters' fixed schedules using the Bombers' Notebook.[5]: 35 The notebook lists twenty characters in need of aid,[5]: 35 such as a soldier who needs medicine and an affianced couple estranged by Skull Kid's mischief. Blue bars on the notebook's timeline indicate when characters are available for interaction, and icons indicate that Link has received items, such as masks, from the characters.[5]: 35

Plot

editSetting and characters

editMajora's Mask is set in Termina, an alternate version of Hyrule which is the main setting of most Zelda games.[10][11] Termina is depicted as a darker, more unsettling version of Hyrule, in which landmarks are familiar but twisted and minor characters who previously appeared in Ocarina of Time are presented with individual stories of misfortune.[12] In the skies above Termina, a grimacing moon threatens to crash and obliterate all life. It is predicted to impact on the eve of the Carnival of Time, an annual harvest festival that begins in three days. Despite the looming threat, the various peoples of Termina are preoccupied by their own respective troubles. In the center of Termina, the people of Clock Town endlessly debate evacuating the city or continuing to prepare for the festival, the failure of which would be devastating to the economy.

Story

editMajora's Mask begins several months after Ocarina of Time.[13] Link seeks his fairy, Navi, who departed after the events of the previous game. During his search, he is ambushed by a Skull Kid wearing a mysterious mask and his two fairy companions, the siblings Tatl and Tael. They steal both his horse, Epona, and the Ocarina of Time. Link pursues them and falls into a trap; Skull Kid curses Link, transforming him into a Deku Scrub, but inadvertently leaves Tatl behind. With no other choice, Tatl guides Link to Clock Town. They meet the Happy Mask Salesman, who pressures Link into recovering the mask that Skull Kid stole, promising to break the curse if he succeeds. After three days, Link manages to locate Skull Kid and retrieve the Ocarina of Time but fails to get the mask. As the moon nears impact, Tael instructs Link to awaken the Four Giants, Termina's guardian deities. Link plays the Song of Time and miraculously returns to the day he first set foot in Termina.

Mistakenly believing that Link recovered the mask, the Happy Mask Salesman breaks Link's curse. He soon discovers that Link failed and flies into a rage. He explains that Skull Kid's mask is Majora's Mask, which contains a powerful evil that can bring about the end of days. After he collects himself, the Happy Mask Salesman dispatches Link to retrieve Majora's Mask. Link embarks on his quest by going to the regions that Tael mentioned: Woodfall, Snowhead, the Great Bay, and Ikana Canyon. Link learns that the four locations are afflicted by Majora's magic. In Woodfall, the swamp is poisoned and the Deku princess was kidnapped. Snowhead has been suffering an eternal winter, driving the Gorons to starvation. Great Bay's waters have been contaminated, turning its creatures into monsters. In Ikana, inhabitants are terrorized by a plague that brings the dead back to life. Through his travels, Link learns that Skull Kid cursed the land as revenge for feeling abandoned by his Giant friends when they became Termina's guardians. Tatl and Tael befriended the lonely Skull Kid and accompanied him in the mischief that led to his theft of the mask, which has been corrupting him ever since. Under the mask's influence, Skull Kid forced the moon on a collision course with Termina.

Across numerous time loops, Link liberates the Giants and summons them on the eve of the Carnival. They manage to halt the moon's descent but Majora's Mask comes alive and possesses the moon itself, abandoning Skull Kid. Link confronts Majora's Mask inside the moon and defeats it. Link, the fairies, and the Giants all make amends with Skull Kid, while the Happy Mask Salesman recovers the now powerless Majora's Mask. The Carnival of Time begins with celebrations based on Link's accomplishments. In a nearby forest, Skull Kid draws himself with Link and his friends on a tree stump.

Development

editWhereas Ocarina of Time needed five years since the previous entry in the series, Link's Awakening, Majora's Mask was released on a much shorter timetable. The game was developed by a team led by Eiji Aonuma, Yoshiaki Koizumi, and Shigeru Miyamoto, with Miyamoto primarily in a supervisory role.[14] It was initially conceived as a remixed "Ura" edition of Ocarina of Time for the disc-based 64DD peripheral for Nintendo 64.[15] Aonuma, who had been in charge of dungeons for Ocarina of Time, was unenthused about simply redesigning them for Ura Zelda so Miyamoto challenged his team to create a new game using the existing game engine and graphics in just one year.[15] By reusing game assets, the smaller team was able to finish Majora's Mask in 15 months.[16][17] The aggressive development schedule resulted in a great deal of 'crunch'—mandatory overtime—and the writers expressed their frustration by inserting complaints about overwork into the script.[18] Another team finished Ura Zelda, but it never came out on the 64DD, which was a commercial failure in Japan and was not released outside its home country.[19] It was later officially titled Ocarina of Time: Master Quest and packaged with pre-ordered copies of The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker for GameCube.[15][20][21]

According to Aonuma, the development team grappled with the question of what kind of game would follow in the wake of Ocarina of Time's success.[22] Aonuma recruited Koizumi, who was designing a repeatable "cops-and-robbers" game that would allow players to have a different experience each time they played it.[14][17] Together, they adapted Koizumi's game into the three-day system to "make the game data more compact while still providing deep gameplay".[14][15][23] Early in development, this system originally rewound a week, but it was shorted as seven days was deemed too burdensome for players to remember and too complex to create in one year.[24] Aonuma cited the 1998 film Run Lola Run as inspiration for the time loop concept.[14] Miyamoto and Koizumi came up with the story that served as the basis for the script written by Mitsuhiro Takano.[25][26][27] Koizumi said the idea for the moon falling came from one of his dreams.[28] Art director Takaya Imamura said that the name "Majora" was a portmanteau of his own surname and "jura", from one of his favorite films, Jurassic Park.[29] Reflecting on the game's mature and melancholy tone, Aonuma felt that players of Ocarina of Time had grown up somewhat and could be motivated by different emotions like sadness and regret. The game's signature sidequest, the Anju and Kafei wedding quest, was intended to highlight the contrast between a joyous occasion and the impending cataclysm.[30] In addition to saving time, the reuse of character models from Ocarina of Time allowed the team to recontextualize them in the more sombre setting.[31]

Majora's Mask first appeared in the media in May 1999, when Famitsu reported that a long-planned Zelda expansion for the 64DD was in development.[32] It had a playable demo at the Nintendo Space World exhibition on August 27, 1999.[33][34] The Space World demo included many elements from the final game, including the large clock that dominates the center of Clock Town, the timer at the bottom of the screen, and mask transformations.[35][36][37] In November, Nintendo announced a "Holiday 2000" release date.[38] The final title was announced in March 2000.[39] The game was supported by a $8 million marketing campaign in America.[40] The game was released on April 27, 2000 in Japan and October 26, 2000 in North America and featured a gold Nintendo 64 cartridge.[41][42]

Technical differences from Ocarina of Time

editMajora's Mask runs on an upgraded version of the engine used in Ocarina of Time and requires the use of the Nintendo 64's 4MB Expansion Pak, making it and Donkey Kong 64 the only two games that require the peripheral.[4] IGN theorized this requirement is due to Majora's Mask's origins as a Nintendo 64DD game, which would necessitate an extra 4MB of RAM.[4] The use of the Expansion Pak allows for greater draw distances, more accurate dynamic lighting, more detailed texture mapping and animation, complex framebuffer effects such as motion blur, and more characters displayed on-screen.[4] This expanded draw distance allows the player to see much farther and eliminates the need for the fog effect and "cardboard panorama" seen in Ocarina of Time, which were used to obscure distant areas.[4] IGN considered the texture design to be one of the best created for the Nintendo 64, saying that although some textures have a low resolution, they are "colorful and diverse", which gives each area "its own unique look".[4]

Music

editThe music was written by longtime series composer Koji Kondo with contributions from Toru Minegishi.[43] The soundtrack largely consists of reworked music from Ocarina of Time, complemented with other traditional Zelda music such as the "Overworld Theme" and new material.[4][6] Kondo described the music as having "an exotic Chinese opera sound".[44] As the three-day cycle progresses, the theme song of Clock Town changes between three variations, one for each day.[45] IGN related the shift in music to a shift in the game's atmosphere, saying that the quickened tempo of the Clock Town music on the second day conveys a sense of time passing quickly.[4] The two-disc soundtrack was released in Japan on June 23, 2000, and features 112 tracks from the game.[46][43]

Reception

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 95/100[b][47] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Edge | 9/10[48] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 10/10[49] |

| Famitsu | 37/40[50][51] |

| Game Informer | 9.75/10[52] |

| GamePro | 4.5/5[53] |

| GameRevolution | A-[55] |

| GameSpot | 8.3/10[6] |

| GamesRadar+ | 4/4[54] |

| IGN | 9.9/10[4] |

| Next Generation | 4/5[56] |

| Nintendo Power | 9.4/10[45] |

| St. Petersburg Times | A+[57] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences | Console Action/Adventure (2001) |

| Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences | Game Design (2001) |

In Japan, The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask sold 601,542 copies by the end of 2000.[58] In the United States, it was the fourth best-selling game of 2000 at 1,206,489 copies.[59] In Europe, it was the eighth highest-grossing game of 2000.[60] Overall, 3.36 million copies were sold worldwide for Nintendo 64.[61]

Like its predecessor, Majora's Mask was lauded critically. The game holds a score of 95/100 on review aggregator Metacritic, indicating "universal acclaim", based on 27 reviews.[47] Many reviews compared it favorably with Ocarina of Time, which is often cited as one of the greatest video games of all time.[62] Critics from the St. Petersburg Times, who previously called Ocarina of Time "the Gone With the Wind of video gaming", claimed Majora's Mask outdid its predecessor.[57] Reviewers did not take issue with the reuse of game engine, control mechanics, and visual assets from Ocarina of Time;[45][49][52][56] Jes Bickham of GamesRadar said they were already "nigh-on perfect after all" and the recycling allowed the development team to concentrate on delivering new content.[54]

Critics praised the game's signature three-day cycle, comparing it to the film Groundhog Day.[49][52][54] Andrew Reiner of Game Informer called it "one of the most inventive premises in all of gaming", and also stated that "without question, Majora's Mask is the finest adventure the Nintendo 64 has to offer".[52] Fran Mirabella III of IGN appreciated the way the time mechanics interacted with mask-based puzzles.[4] Some critics found that the time restrictions made it one of the most challenging games in the series.[57][51][49][45][6] The Famitsu reviewer suggested that the three-day cycle increased replay value.[51] On the other hand, Jeff Gerstmann of GameSpot felt that the cyclic structure put too much focus on minigames and sidequests.[6]

Multiple outlets took note of its darker tone and story compared to other games in The Legend of Zelda series. Matt Casamassina of IGN described the game as "The Empire Strikes Back of Nintendo 64", making an analogy to the film's status as a more mature and sophisticated sequel to Star Wars.[4] Edge magazine referred to Majora's Mask as "the oddest, darkest and saddest of all Zelda games".[63] The GamePro reviewer characterized the story as "surreal and spooky, deep, and intriguing" and the game as "living proof that the N64 still has its magic".[53] Johnny Liu of GameRevolution wrote that it "takes a little longer to get into this Zelda", but also that "there are moments when the game really hits you with all its intricacies and mysteries, and that makes it all worthwhile".[55]

Majora's Mask was a runner-up for GameSpot's "Best Nintendo 64 Game" award, losing to Perfect Dark. It was also nominated for "Best Adventure Game" among console games.[64] During the 4th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, Majora's Mask was honored with the "Console Action/Adventure" and "Game Design" awards; it also received nominations for "Console Game of the Year" and "Game of the Year".[65]

Legacy

editMajora's Mask makes consistent appearances on lists of the best games in the Zelda series,[c] as well as the greatest games of all time.[d] It has also placed highly in fan-voted polls.[e] Critics have compared it favorably to its closest contemporary, Ocarina of Time. Writing for Polygon, Danielle Riendeau observed that Ocarina of Time provided the foundations for Majora's Mask to become the "most innovative" game in the series on a structural level. She commended the way it shifted the focus away from the "chosen hero" narrative common in the series to the myriad people that Link meets on his adventure, most of whom were given more compelling characterization than in Ocarina of Time.[94] Tomas Franzese of Digital Trends saw Majora's Mask as the template for the way Tears of the Kingdom later retrofitted new mechanics onto the world of Breath of the Wild.[95] Marty Sliva of The Escapist placed it in conversation with Zelda II: The Adventure of Link in the way it challenged series conventions.[96]

Retrospective analyses of the game recognize its mature themes and complex time loop gameplay. Yahtzee Croshaw of The Escapist opined that its progress-resetting mechanics defied prevailing game design trends that prioritized player empowerment and a game of its type was unlikely to be repeated due to the conservatism of big-budget game development.[97] Sliva identified the short development cycle and reuse of assets as a limitation that sparked the design team's creativity.[98] Jonathan Holmes of Destructoid called Majora's Mask a game about "being a young adult", with all the responsibility and confusion that entails. He saw Link as an adult in a child's body who must step up when the other adults in the game fail to do so in the face of crisis.[99] The existential horror of the falling moon is another common topic of analysis, providing both pathos and a prism to understand the themes of loneliness and forgiveness.[100][101] Majora's Mask has been cited as a thematic and mechanical inspiration for games such as Kena: Bridge of Spirits,[102] Outer Wilds,[103] and Elsinore,[104] among others.[105][106] Author and literary critic Gabe Durham of Boss Fight Books has also observed the game's influence on films like Source Code and Edge of Tomorrow.[14]

Ports and emulated releases

editIn 2003, Nintendo rereleased Majora's Mask on the GameCube as part of The Legend of Zelda: Collector's Edition, a special promotional disc which also contained three other The Legend of Zelda games and a twenty-minute demo of The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker.[107] This disc came bundled with a GameCube console, as part of a subscription offer to Nintendo Power magazine, or through Nintendo's official website.[108] The Collector's Edition was also available through the Club Nintendo reward program,[109] with a bonus discount offered in 2004 with the purchase of The Legend of Zelda: Four Swords Adventures during the month-long "Zelda Collection" campaign.[110]

Similar to other GameCube rereleases, versions of the games featured in the Collector's Edition are emulations of the originals using GameCube hardware. The only differences are minor adjustments to button icons to resemble the buttons on the GameCube controller. Majora's Mask also boots with a disclaimer that some of the original sounds from the game may cause problems due to their emulation.[107] Aside from these deliberate changes, GameSpot's Ricardo Torres found that the frame rate "appears choppier" and noted inconsistent audio.[111] The GameCube version also features a slightly higher native resolution than its Nintendo 64 counterpart, as well as progressive scan.[107]

Majora's Mask was released on the Wii's Virtual Console service in Europe and Australia on April 3, 2009,[112] and Japan on April 7.[113] It was later released in North America on May 18 and commemorated as the 300th Virtual Console game available for purchase in the region.[114] During January 2012, Club Nintendo members could download Majora's Mask onto the Wii Console at a discount.[115] A similar deal was offered at the discontinuation of Club Nintendo in 2015.[116] The game was released for the Wii U's Virtual Console service in Europe on June 23, 2016[117] and in North America on November 24.[118] Majora's Mask was released through the Nintendo Switch Online Expansion Pack service on February 25, 2022.[119][120]

Nintendo 3DS remake

editAfter the release of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D, a remake for the Nintendo 3DS, director Eiji Aonuma suggested that a Majora's Mask remake was dependent on interest and demand.[121] Following this news, a fan campaign called "Operation Moonfall" was launched to demonstrate that demand.[122] The campaign name is a reference to a similar fan-based movement, Operation Rainfall, set up to persuade Nintendo of America to localize a trio of role-playing games for the Wii.[122] The petition reached 16,000 signatures after a week.[123] Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé acknowledged the campaign but said that the ultimate decision would be based on financial projections rather than a fan petition.[124] Both Zelda producer Eiji Aonuma[125] and Miyamoto expressed interest in developing the remake.[126][127]

The remake, titled The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D, was released worldwide in February 2015. Like Ocarina of Time 3D before it, the remake features improved character models and stereoscopic 3D graphics, along with altered boss battles, an additional fishing minigame, and compatibility with the New Nintendo 3DS, particularly its second analog stick used for camera control.[128][129] To update the game for modern audiences, Aonuma and the team at Grezzo compiled a list of gameplay moments that stuck out to them as unreasonable for players, colloquially dubbed the "what in the world" list.[130] The game's release coincided with the launch of the New Nintendo 3DS system in North America and Europe.[131] A special edition New Nintendo 3DS XL model was launched alongside the game,[132] with the European release featuring a pin badge, double-sided poster, and steelbook case.[133] The UK retailer Game offered a Majora's Mask-themed paperweight as a pre-order bonus for the standard edition of the game.[134]

Cultural impact

editMajora's Mask was the primary inspiration for the 2010s web serial Ben Drowned by Alexander D. Hall, which helped define the creepypasta genre of online storytelling.[135][136][137] Building on the horror elements of the game, Ben Drowned is framed as an urban legend about a "haunted" Majora's Mask game cartridge that causes unexplainable events in-game and in the player's real life. Eric Van Allen of Kotaku compared it to a campfire story adapted for the digital age.[135] Victor Luckerson of The Ringer attributed part of Majora's Mask's enduring cult following to its ambiguous themes, malleable and receptive to reinterpretations like Ben Drowned.[138] Sliva considered Ben Drowned an inextricable part of the game's wider legacy.[96]

Features based on Majora's Mask have also appeared in the Super Smash Bros. series. A stage based on the Great Bay appears in Super Smash Bros. Melee and Super Smash Bros. Ultimate.[139] Skull Kid appears as a computer-controlled Assist Trophy in Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U[140][141] and Ultimate, while the Moon appears as an Assist Trophy in Ultimate as well.[142] A Skull Kid-themed mask is available as customizable headgear to be worn by Mii characters in Nintendo 3DS and Wii U[143] and Ultimate.[144]

Ember Lab made an animated short film called Terrible Fate in 2016, based on characters from Majora's Mask.[145][146][102] The studio would later develop Kena: Bridge of Spirits as a "natural next step".[102]

Notes

edit- ^ Japanese: ゼルダの伝説 ムジュラの仮面, Hepburn: Zeruda no Densetsu: Mujura no Kamen

- ^ Based on 27 reviews.

- ^ Supported by multiple references.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72]

- ^ Supported by multiple references.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90]

- ^ Supported by multiple references.[91][92][93]

References

edit- ^ Robinson, Nikole (April 15, 2023). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask: Inside the Surrealist Sequel That Was Never Supposed to Exist". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ MacDonald, Keza (November 6, 2014). "Why The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Still Matters". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Mejia, Ozzie (November 12, 2014). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask - Explaining Its Cult Following". Shacknews. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mirabella III, Fran (October 25, 2000). "Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". IGN. Archived from the original on February 6, 2005. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Instruction Booklet (PDF). Nintendo. October 25, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2024.[ The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask instruction booklet]. (PDF)

- ^ a b c d e Gerstmann, Jeff (October 25, 2000). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 9, 2003. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Frear, Dave (February 25, 2022). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Review". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Strategy Guide - Masks". IGN Guides. 2000. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Strategy Guide - Anju and Kafei Notebook Entry". IGN Guides. 2000. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Great Hyrule Encyclopedia". Zelda Universe. Nintendo. Archived from the original on December 15, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask at Nintendo.com". Nintendo.com. Nintendo. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

Link must save the world! This time, he finds himself trapped in Termina, an alternate version of Hyrule that is doomed to destruction in just three short days.

- ^ Oxford, Nadia (April 27, 2020). "The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild 2 Needs to Be as Weird as Majora's Mask". USgamer. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "新しい「ゼルダ」の世界" [A new "Zelda" world]. Nintendo.co.jp (in Japanese). Nintendo. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

舞台は、前作『時のオカリナ』での活躍から数ヶ月後の世界。

[The stage is the world a few months after the exploits of the previous work "Ocarina of Time".] - ^ a b c d e Durham, Gabe (April 30, 2020). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Was Never Supposed to Exist". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Iwata, Satoru (November 19, 2009). "Iwata Asks: The Legend of Zelda: Spirit Tracks - The Previous Game Felt As Though We'd Given Our All". Nintendo.com. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Yoon, Andrew (October 16, 2013). "Zelda's Eiji Aonuma on Annualization, And Why the Series Needs 'A Bit More Time'". Shacknews. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "宮本 茂 の ロクヨン魂" [Shigeru Miyamoto's N64 Spirit]. Dengeki Nintendo 64 (in Japanese). No. 53. ASCII Media Works. October 2000. pp. 96–97. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Nightingale, Ed (January 4, 2023). "Majora's Mask's Most Infamous Line Is Actually All About Crunch". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff, live (August 25, 2000). "Ura-Zelda Complete". IGN. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (December 4, 2002). "Zelda Bonus Disc Coming to US". IGN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff, live (April 15, 2003). "Limited Edition Zelda in Europe". IGN. Archived from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Aonuma, Eiji (March 25, 2004). "GDC 2004: The History of Zelda". IGN. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Iwata, Satoru (February 13, 2015). "Iwata Asks: The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D - Make It in a Year". Nintendo.com. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (February 13, 2015). "Zelda: Majora's Mask Time Mechanic Originally Rewound a Week". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Leung, Jason (July 7, 2000). "Jason Leung (Author of English Screen Text) Diary Part I". Nintendo.com. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on June 26, 2001. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (December 4, 2007). "Interview: Super Mario Galaxy Director On Sneaking Stories Past Miyamoto". Wired: GameLife. Condé Nast Digital. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Edge Staff (February 6, 2008). "Interview: Nintendo's Unsung Star". Edge Magazine. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ East, Thomas (July 5, 2011). "Zelda: Majora's Mask Came to Me in a Dream - Koizumi". The Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Norman, Jim (July 4, 2023). "Random: Zelda: Majora's Mask's Title Was Inspired By Jurassic Park, Says Takaya Imamura". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Totilo, Stephen (February 17, 2015). "How A Zelda Dungeon Is Made". Kotaku. Archived from the original on January 6, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Hilliard, Kyle (February 21, 2015). "Zelda Producer Eiji Aonuma Talks Creating Majora's Mask And His Personal Hobbies". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (May 11, 1999). "Nintendo Sequel Rumblings". IGN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff, live (June 16, 1999). "Zelda Sequel Invades Spaceworld". IGN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Space World '99". Game Informer. No. 79. Funco, Inc. November 1999. pp. 24–25.

- ^ IGN Staff (August 4, 1999). "First Screenshots of Zelda Gaiden!". IGN. Archived from the original on October 31, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: The Continuing Saga Preview". Game Informer. No. 79. Funco, Inc. November 1999. p. 42.

- ^ IGN Staff (August 19, 1999). "First Zelda Gaiden Details Exposed". IGN. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (November 4, 1999). "Gaiden for Holiday 2000". IGN. Archived from the original on August 17, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (March 6, 2000). "Zelda Gets a New Name, Screenshots". IGN. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Gaudiosi, Peyton. "Zelda Squares off Against PS2". Video Business. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (April 5, 2000). "Majora's Mask Commercials Online!". IGN. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (October 4, 2000). "Have You Reserved Your Gold?". IGN. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ a b IGN Staff (June 30, 2000). "Zelda Soundtrack Released". IGN. Archived from the original on April 2, 2002. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Inside Zelda Part 4: Natural Rhythms of Hyrule". Nintendo Power. Vol. 195. Nintendo of America. September 2005. pp. 56–58.

- ^ a b c d "Now Playing". Nintendo Power. Vol. 137. Nintendo of America. October 2000. p. 112. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "ゼルダの伝説 ムジュラの仮面 オリジナルサウンドトラック" [The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Original Soundtrack]. Nintendo.co.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on September 18, 2000. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Nintendo 64 Critic Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 16, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend Of [sic] Zelda: Majora's Mask". Edge. No. 92. Christmas 2000. pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b c d MacDonald, Mark; Sewart, Greg; Lockhart, Ryan (December 2000). "Review Crew: The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 137. Ziff Davis. p. 209. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "ニンテンドウ64 – ゼルダの伝説 ムジュラの仮面". Famitsu (in Japanese). No. 915. June 30, 2006. p. 30.

- ^ a b c IGN Staff (April 20, 2000). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Reviewed!". IGN. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Reiner, Andrew (November 2000). "Legend of Zelda Majora's Mask". Game Informer. No. 91. p. 136. Archived from the original on September 20, 2003. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b The Freshman (October 30, 2000). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". GamePro. Archived from the original on February 25, 2004. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Bickham, Jes (January 20, 2002). "Games Radar UK Review - Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on January 20, 2002. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Liu, Johnny (November 1, 2000). "Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask - N64". GameRevolution. Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Orlando, Greg (December 2000). "Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask" (PDF). Next Generation. Vol. 3, no. 12. p. 115. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Carter, Chip; Carter, Jonathan (November 6, 2000). "New Zelda for N64 Leaves Them Moonstruck". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "2000年ゲームソフト年間売上TOP100" [2000 Game Software Annual Sales Top 300]. Famitsū Gēmu Hakusho 2001 ファミ通ゲーム白書2001 [Famitsu Game Whitebook 2001] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Enterbrain. 2001. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ GameSpot Staff (January 16, 2001). "The Best-Selling Games of 2000". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Milia 2001: Pokémon, Les Champions Eccsell" [Milia 2001: Pokémon, the Eccsell champions]. 01net (in French). February 14, 2001. Archived from the original on June 19, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Parton, Rob (March 31, 2004). "Xenogears Vs. Tetris". RPGamer. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (2005). "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Time Extend – The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". Edge. No. 143. December 2004. p. 121.

In the first of our second sittings with important titles of recent years, we look at the oddest, darkest and saddest of all Zelda games.

- ^ GameSpot Staff (January 5, 2001). "Best and Worst of 2000". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 13, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "4th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on June 4, 2002. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Roberts, David; Wald, Heather; Loveridge, Sam; Gould-Wilson, Jasmine; West, Josh (July 26, 2023). "The 10 Best Zelda Games of All-Time". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on July 28, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Watts, Steve (May 25, 2023). "Best Zelda Games, Ranked - Where Does Tears Of The Kingdom Fall?". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (May 15, 2023). "The 10 Best Legend of Zelda Games of All Time". IGN. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Monbleau, Timothy (May 11, 2023). "The 10 Best Zelda Games of All Time, Ranked". Destructoid. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Welsh, Oli; Myers, Maddy; Diaz, Ana; Mahardy, Mike; McWhertor, Michael (December 31, 2023). "The Legend of Zelda Games, Ranked". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Shepard, Kenneth (April 10, 2023). "The Mainline Legend Of Zelda Games, Ranked From Worst To Best". Kotaku. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Gray, Kate (December 25, 2021). "We Worked Out The Best Zelda Game Once And For All, Using Maths". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games Of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Game Informer Staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79.

- ^ "The Top 300 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 300. April 2018.

- ^ Polygon Staff (November 28, 2017). "The 500 Best Games of All Time: 400-301". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Slant Staff (June 9, 2014). "100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Slant Staff (June 8, 2018). "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Slant Staff (April 13, 2020). "The 100 Best Video Games of All Time". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on January 14, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ EGM Staff (January 2002). "Top 100 Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 150. Archived from the original on June 20, 2003. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Greatest 200 Video Games of Their Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 200. February 2006. p. 76. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. Vol. 200. Nintendo of America. February 2006. pp. 58–66.

- ^ East, Tom (February 23, 2009). "100 Best Nintendo Games: Part 3". Official Nintendo Magazine UK. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ White, Sam; Leedham, Robert (May 10, 2023). "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time, Ranked by Experts". British GQ. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (November 30, 2007). "IGN's Top 100 Games 2007: 31. The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". IGN. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (March 30, 2018). "Top 100 Video Games of All Time". IGN. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Edge Staff (August 2017). "Edge Presents: The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Edge. No. 308.

- ^ Tony Mott, ed. (2013). 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die. Universe Publishing. ISBN 978-1844037667.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt (December 5, 2015). "HG101 Presents: The 200 Best Video Games of All Time". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Games of All Time". GamesTM. No. 200. May 2018.

- ^ IGN Staff. "The Greatest Legend of Zelda Game Tournament". IGN. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Bankhurst, Adam (May 12, 2023). "The Legend of Zelda Face-Off: The Best Game Revealed". IGN. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Romano, Sal (December 27, 2021). "Over 50,000 Japanese Users Vote for Their Favorite Console Games in TV Asahi Poll – Top 100 Announced". Gematsu. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Riendeau, Danielle (February 12, 2015). "Majora's Mask Is Better Than Ocarina of Time". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 28, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Franzese, Tomas (May 11, 2023). "Before Tears of the Kingdom, Pay Your Respects to Majora's Mask". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Sliva, Marty (May 4, 2023). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Isn't Just a Video Game". The Escapist. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Croshaw, Yahtzee (March 17, 2015). "Why the N64 Majora's Mask Could Not Be Made Today As a AAA Title". The Escapist. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Sliva, Marty (April 28, 2020). "20 Years Later, The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask Proves That Games Should Get Weird". The Escapist. Archived from the original on November 10, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Holmes, Jonathan (November 9, 2014). "Majora's Mask Is My Favorite Game About Being a Young Adult". Destructoid. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Winslow, Levi (October 29, 2021). "Majora's Mask Is A Masterpiece Of Existential Horror". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 11, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Petit, Carolyn (March 3, 2015). "In the Mouth of the Moon: A Personal Reading of 'Majora's Mask'". Waypoint. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Grier, Josh (June 11, 2020). "Kena: Bridge of Spirits from Indie Studio Ember Lab Announced for PS5". PlayStation Blog. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Shanley, Patrick (May 20, 2019). "'Majora's Mask' Meets 'Apollo 13': Inside Annapurna Interactive's 'Outer Wilds'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Wright, Steven (December 22, 2016). "Making Grand Video Game Tragedy in 'Elsinore'". Waypoint. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Benson, Julian (February 3, 2017). "Britsoft Focus: How Cavalier Games Made the Anti-Hitman". Kotaku UK. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Batchelor, James (July 31, 2019). "Learn, Reset, Repeat: The Intricacy of Time Loop Games". GamesIndustry.biz. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c IGN Staff (November 17, 2003). "Legend of Zelda: Collector's Edition". IGN. Archived from the original on February 16, 2004. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ IGN Staff (November 4, 2003). "Zelda Bundle at $99". IGN. Archived from the original on April 6, 2004. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Yong, Song-Chan (February 10, 2004). "클럽 닌텐도를 통해 게임큐브용 젤다 컬렉션을 Get!" [Get the Zelda Collection for the GameCube through Club Nintendo]. GameMeca (in Korean). Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "シリーズ4タイトルのgc版を収録した『ゼルダコレクション』の入手方法が明らかに!" ["Zelda Collection" ["The Legend of Zelda: Collector's Edition"] containing GameCube versions of four titles in the series revealed]. Dengeki Online (in Japanese). February 9, 2004. Archived from the original on July 30, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Torres, Ricardo (November 14, 2003). "The Legend of Zelda Collector's Edition Bundle Impressions". GameSpot. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Robinson, Andy (April 3, 2009). "Zelda: Majora's Mask on Euro VC". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Fletcher, JC (April 7, 2009). "VC/WiiWare Tuesday: Majora's Mask Arrives in Another Region". Joystiq. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Zelda Classic Becomes 300th Virtual Console Game". Nintendo.com. Nintendo of America. May 18, 2009. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Pereira, Chris (January 11, 2011). "Club Nintendo Now Offering Majora's Mask, Kirby, And Dr. Mario". 1UP. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Macy, Seth G. (February 2, 2015). "Here They Are: The Final Club Nintendo Rewards". IGN. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". Nintendo.it. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask". Nintendo.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (October 15, 2021). "Nintendo Switch Online's N64 and Sega Genesis 'Expansion Pack' Launches October 25th for $49.99 per Year". The Verge. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Nelson, Will (February 18, 2022). "'Majora's Mask' Gets New Trailer Ahead of Next Week's Switch Online Launch". NME. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ MacDonald, Keza (July 25, 2011). "Majora's Mask Remake Is a Possibility". IGN. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Sterling, James Stephanie (July 28, 2011). "Operation Moonfall Plans to Get Majora's Mask on 3DS". Destructoid. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Starkey, Daniel (August 13, 2011). "Interview: Operation Moonfall". Destructoid. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Moore, Joshua (December 4, 2013). "Nintendo's Reggie Talks Wii U, Western Development And Operation Rainfall". Siliconera. Archived from the original on August 30, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Gudmundson, Carolyn (November 9, 2011). "Zelda, Past and Future: An Interview with Koji Kondo and Eiji Aonuma". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

Eiji Aonuma: I did hear that there's a website here that was launched in North America by some people that are hoping we'll release a 3D version of Majora's Mask. Of course I'm very flattered to hear that so many people are asking for that game, so I hope that at some point in the future hopefully, maybe, we'll be able to do something with it.

- ^ George, Richard (June 12, 2012). "Zelda 3DS: It's Majora's Mask Vs. Link to the Past". IGN. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ George, Richard (June 20, 2013). "Nintendo Still Thinking About Majora's Mask Remake". IGN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Haywald, Justin (November 5, 2014). "The Legend of Zelda Majora's Mask Confirmed for Nintendo 3DS". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Iwata, Satoru (February 13, 2015). "Iwata Asks: The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D - "Moon Gazing" With the C-Stick". Nintendo.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Iwata, Satoru (February 13, 2015). "Iwata Asks: The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D - The "What in The World" List". Nintendo.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (February 18, 2015). "Nintendo Really Likes Metacritic". Kotaku Australia. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

The two software titles which were released simultaneously with the New Nintendo 3DS hardware in the U.S. and Europe, "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D" and "Monster Hunter 4 Ultimate"

- ^ Burleson, Kyle MacGregor (January 14, 2015). "Majora's Mask Launches February 13 with a Limited Edition New 3DS XL". Destructoid. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Sahdev, Ishaan (November 5, 2014). "The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask 3D Gets A Special Edition In Europe". Siliconera. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (December 22, 2014). "Majora's Mask 3D GAME Pre-Order Bonus Is a Commemorative Paperweight". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Van Allen, Eric (October 26, 2017). "The Zelda Ghost Story That Helped Define Creepypasta". Kotaku. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Good, Owen (September 11, 2010). "The Haunting Of A Majora's Mask Cartridge". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Conlon, Liam (June 28, 2019). "Zelda Is at Its Best When It Embraces Horror". Waypoint. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Luckerson, Victor (March 3, 2017). "The Cult of 'Zelda: Majora's Mask'". The Ringer. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Elton (August 9, 2018). "Super Smash Bros. Ultimate Full Stage List". Heavy. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Otero, Jose (December 6, 2013). "Skull Kid Is an Assist Trophy in Super Smash Bros. For Wii U". IGN. Archived from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Carter, Chris (December 6, 2013). "Majora's Mask's Skull Kid to Be an Assist in Smash Bros". Destructoid. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Saunders, Toby (December 6, 2018). "Smash Ultimate Assist Trophy List - Complete List of Assist Trophies". GameRevolution. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ GamesRadar Staff (April 1, 2015). "Mewtwo Comes to Smash Bros. Wii U/3DS In April, Lucas in June, Plus More DLC". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Newell, Adam (December 6, 2018). "Here Are All the Mii Fighter Costumes Available in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate". Dot Esports. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (June 11, 2020). "Kena: Bridge of Spirits Is a Story of Redemption with Cute Characters on the PS5". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (October 22, 2021). "Sony's Breakout Video Game Owes Its Success to a Hazmat Suit". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2024.