You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (June 2011) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

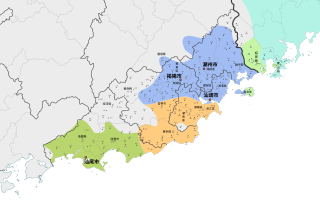

Haklau (simplified Chinese: 学佬话/福佬话; traditional Chinese: 學佬話/福佬話), or Hai Lok Hong (海陆丰话; 海陸豐話),[5] also known as Haifeng dialect (海丰话; 海豐話) or Hailufeng Minnan, is a variety of Southern Min spoken in Shanwei, Guangdong province, China. While it is related to Teochew and Hokkien, its exact classification in relation to them is disputed.[6][7]

| Haklau | |

|---|---|

| Hai Lok Hong, Hailufeng | |

| 學佬話/福佬話 Hok-láu-ōe 海陸豐話 Hái-lio̍k-hong-ōe | |

| Region | Mainly in Shanwei, eastern Guangdong province. |

Native speakers | 2.65 million (2021)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| ISO 639-6 | hife |

| Glottolog | None |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-jik (Haifeng) 79-AAA-jij (Lufeng) |

Haklau Min in Shanwei | |

| Haklau Min | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 海陸豐話 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 海陆丰话 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Etymology

editThe word Haklau (學佬 Ha̍k-láu, also written as 福佬) is the Southern Min pronuciation of Hoklo, originally a Hakka exonym for the Southern Min speakers, including Hoklo and Teochew people. Although originally it was perceived as a derogatory term, speakers of the Hai Lok Hong Min in Shanwei self-identify as Haklau and distinguish themselves from Teochew people. Overseas Hai Lok Hong people still do not like this appellation.[8]

Historically, the Hai Lok Hong region was not a part of Teochew prefecture (潮州府, the region currently known as Teo-Swa or Chaoshan), but was included in the primarily Hakka-speaking Huizhou prefecture (惠州府). Modern Huizhou city (particularly the Huidong County) also has a Haklau-speaking minority.

The word Hai Lok Hong (海陸豐 Hái-lio̍k-hong) is a portmanteau of Hai Hong (海豐, Mandarin Haifeng) and Lok Hong (陸豐, Mandarin Lufeng), where it is mainly spoken. The character 陸 has multiple pronunciations in Southern Min: the reading le̍k is vernacular, it is common in Teochew, but rarely used in Hokkien and Hai Lok Hong itself; the reading lio̍k (Hokkien, Hai Lok Hong) or lo̍k (Teochew) is literary and commonly used in Hokkien and Hai Lok Hong, but not Teochew, yet its Teochew rendering is the source of English Hai Lok Hong.

Classification

editThe Language Atlas of China classifies Hai Lok Hong as part of Teochew.[9] Other classifications pinpoint the phonological features of Hai Lok Hong that are not found in Teochew, but instead are typical for Chiangchew Hokkien. These features include:[10]

- the final /-i/ in characters like 魚 hî 'fish', 語 gí 'language', and the final /-u/ in 自 chū 'self', 事 sū 'matter', as in Chiangchew Hokkien. Northern Teochew has /-ɯ/ in these words, while Southern Teochew (the Teoyeo dialect) has them with /-u/.

- the final /-uĩ/ in words like 門 mûi 'door; gate', 光 kuiⁿ 'light'. Teochew has them with /-ɯŋ/ or /-uŋ/.

- the finals /-e/ (坐 chě 'to sit', 短 té 'short'), /-eʔ/ (節 cheh 'festival', 截 che̍h 'to cut') and /-ei/ (雞 kei 'chicken', 街 kei 'street'), as in rural southern dialects of Hokkien (such as Zhangpu, Yunxiao, or Chawan), corresponding to Teochew /-o/, /-oiʔ/ and /-oi/. Conservative Northern Hokkien dialects have these words with /-ə/, /-əeʔ/, and /-əe/ respectively.

- the preservation of the codas /-n/ and /-t/ (as in 民 mîn 'people; nation' and 骨 kut 'bone'), which are merged with /-ŋ/ and /-k/ in most dialects of Teochew.

Still, Hai Lok Hong also has features typical for Teochew, but not Hokkien, such as:

- the preservation of 8 tones, pronounced similarly to Northern Teochew. Most dialects of Hokkien only have 7 citation tones.

- the final /-uaŋ/ in 況 khuàng 'situation', 亡 buâng 'to perish', which has merged with /-oŋ/ in Hokkien.

- less extensive denasalization: Hai Lok Hong and Teochew differentiate between 逆 nge̍k 'to go against' and 玉 ge̍k 'jade' , or 宜 ngî 'suitable' and 疑 gî 'doubt', while in Hokkien, these pairs are merged (ge̍k and gî respectively).

Lexically, Hai Lok Hong also shares some traits with Teochew: 個 kâi '(possessive particle)', 愛 àiⁿ 'to want', 睇 théi 'to see' — compare Hokkien 兮 --ê, 卜 beh and 看 khòaⁿ.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Reclassifying ISO 639-3 [nan]: An Empirical Approach to Mutual Intelligibility and Ethnolinguistic Distinctions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-19.

- ^ Mei, Tsu-lin (1970), "Tones and prosody in Middle Chinese and the origin of the rising tone", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 30: 86–110, doi:10.2307/2718766, JSTOR 2718766

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1984), Middle Chinese: A study in Historical Phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, p. 3, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2023-07-10). "Glottolog 4.8 - Min". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7398962. Archived from the original on 2023-10-13. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ^ PENG, Zhigang. 海陆丰福佬方言的语音及词义特点研究 [A Study on the Phonetic and Lexical Features of Hai Lok Hong Haklau dialect]. 文化创新比较研究 (32).

- ^ "Cháozhōuhuà pīnyīn fāng'àn / ChaoZhou Dialect Romanisation Scheme". sungwh.freeserve.co.uk (in Chinese and English). Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Campbell, James. "Haifeng Dialect Phonology". glossika.com. Archived from the original on 2007-08-14. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ 探索汕尾海陆丰福佬(鹤佬)话民系.

- ^ Language atlas of China (2nd edition), City University of Hong Kong, 2012, ISBN 978-7-10-007054-6.

- ^ 潘家懿; 鄭守治 (2010-03-01). "粵東閩南語的分布及方言片的劃分". 臺灣語文研究. 5 (1): 145–165. doi:10.6710/JTLL.201003_5(1).0008.