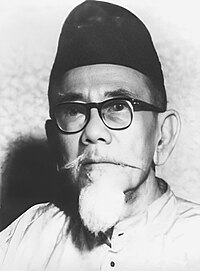

Haji Agus Salim ([ˈaɡʊs ˈsalɪm]; 8 October 1884 – 4 November 1954) was an Indonesian journalist, diplomat, and statesman. He served as Indonesia's Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1947 and 1949.

Agus Salim | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Foreign Minister of Indonesia | |

| In office 3 July 1947 – 19 December 1948 | |

| Prime Minister | Amir Sjarifuddin Mohammad Hatta |

| Deputy | Tamsil St. Narajau |

| Preceded by | Sutan Syahrir |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Andries Maramis |

| In office 4 August 1949 – 20 December 1949 | |

| Prime Minister | Mohammad Hatta |

| Deputy | Tamsil St. Narajau |

| Preceded by | Alexander Andries Maramis |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad Roem |

| 1st Deputy Foreign Minister of Indonesia | |

| In office 12 March 1946 – 26 June 1947 | |

| Prime Minister | Sutan Syahrir |

| Preceded by | inaugural |

| Succeeded by | Tamsil St. Narajau |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Masjhoedoelhaq Salim 8 October 1884 Koto Gadang, Agam, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 4 November 1954 (aged 70) Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Resting place | Kalibata Heroes' Cemetery, Jakarta |

| Political party | Islamic Union Party (PSII) |

| Spouse | Zainatun Nahar |

| Profession | Journalist, diplomat |

Early life

editAgus Salim was born Masjhoedoelhaq Salim on 8 October 1884, in the village of Koto Gadang, a suburb of Fort de Kock. His father, Sultan Mohammad Salim, was a colonial prosecutor and judge whose highest rank was chief judge for the indigenous court in Tanjung Pinang. His birth name, which translates into "defender of truth", was changed to Agus Salim early in his childhood.[1]

Salim received his elementary education at Europeesche Lagere School; at that time, it was considered a privilege for a non-European child to attend an all-European school. He continued his studies at the Hogere Burgerschool in Batavia and graduated with the highest score in the whole Dutch East Indies. Salim's father had applied (and was granted) for his two sons, Agus and Jacob, to be granted equal status with the Europeans. However, his efforts to secure a government scholarship to study medicine in the Netherlands fell short. Kartini, another European-educated student whose writings on women's rights and emancipation became famous later, offered to defer her scholarship for Salim; this, too, was rejected.[2]

C.S. Hurgronje, a prominent colonial administrator best known for his study of native affairs, took Salim under his wing and arranged for him to leave the Indies in 1905 to work as an interpreter and secretary at the Dutch consulate in Jeddah, where he handled hajj affairs; in some way, it was to distance him from the radical teachings of a close relative, the well-known Shafi'i imam of Masjid al-Haram Ahmad Khatib al-Minangkabawi.[1]

Salim returned to the Indies in 1911 and pursued a career in journalism, contributing pieces for magazines and publications like Hindia Baroe, Fadjar Asia, and Moestika. He would later serve as an editor in Neratja, a newspaper aligned with the Sarekat Islam, where he was also an active member. While in that, he founded a private Hollandsche Indische School in his hometown of Koto Gadang, but left after three years to return to Java.

Political activism

editSalim became one of the most vocal advocates of the growing Indonesian nationalist movement, in the period known as the National Awakening. He became a prominent leader in Sarekat Islam and was considered the right-hand man of its leader, Oemar Said Tjokroaminoto. The SI contained many political strains, including communists, business leaders, and Islamically-minded reformers. Having spent time in the Hejaz, Salim was considered to be on the reformist side of the SI and was at odds with the increasingly leftist faction of SI led by Semaun, Tan Malaka, and Darsono; who would eventually break with SI to found the Communist Union of the Indies.

Salim was occasionally accused by those leftists of being too close to the Dutch colonial government. First, his newspaper Neratja had been funded in 1917 with government money (under the direction of Governor-General Johan Paul van Limburg Stirum) who wanted a Malay-language forum for perspectives sympathetic to the Dutch Ethical Policy,[3] However, by 1918 Neratja became a harsh critic of the colonial government, regularly printing reports of mistreatment of Muslims in remote regions of the Indies.[3] Nonetheless, allegations continued to surface from the left. The Dutch communist Henk Sneevliet accused Neratja editor Abdul Muis of having advocated for his expulsion from the Indies in 1917.[4] And when Salim's Neratja was the only Malay language newspaper to applaud his expulsion in 1918, its editors were condemned by other newspapers and forced to apologize.[4] Even in the late 1920s, as many communists in the Indies were being sent to concentration camps in Boven Digoel, disputes were still arising over Salim's behavior in 1917. In 1927 Bintang Timoer published allegations that Agus Salim had joined Sarekat Islam and other meetings in the 1910s delivered reports to government officials and then used government money to criticize communists in Neratja.[5] Salim responded that he needed money to continue his activities and that everyone profited from the government in some way or other.[6]

Later, after the breakup of the Sarekat Islam, Salim (along with Tjokroaminoto) co-founded the Islamic Union Party (Partai Serikat Islam, PSI), which later became the PSII. After Tjokro died in 1934, Salim became the party's intellectual leader.

In 1921, Salim was appointed to the Volksraad, the Indies' mainly symbolic and advisory quasi-legislature, representing Sarekat Islam. Despite being a proficient speaker of the Dutch language, he insisted on delivering his speeches in Malay, the first member of the council to do so despite hostile reception from other European members. He left the chamber in 1924, frustrated by the chamber's powerlessness (its main function was solely to advise the Governor-General), and derided it as a mere komedi omong (talking comedy).[7] Being an outspoken advocate of social change within the Indonesian Islamic community, Salim was widely known for his unorthodoxy on social issues. At the 1927 convention of the national Islamic organization Jong Islamieten Bond (JIB) in Surakarta, Salim ripped apart the curtained divider between men's and women's seating area and proceeded to deliver his speech titled De sluiering en afzondering der vrouw ("On Veiling and Separation of Women").

Another area of activism that Salim was active in was workers' welfare. At the request of the prominent Dutch trade union Nederlands Verbond van Vakverenigingen (NVV), he served as an advisor for its delegation to the 1929 and 1930 International Labour Conventions, both held in Geneva, Switzerland.

It was alleged that throughout his early years returning from Jeddah, Salim had been in contact with or possibly working for the Politieke Inlichtingen Dienst (PID), the Dutch East Indies's principal state security and intelligence service. Allan Akbar, a historian, conceded that Salim had been asked for a favour by Datuak Tumangguang, a prominent Minangkabau advisor to the colonial government, to covertly enter Sarekat Islam, especially to investigate the relationship between Tjokroaminoto and the Germans.[8] For six weeks, Salim investigated the Sarekat from within, but in a strange twist of history, decided to join the organization of his own will.

Japanese occupation

editDuring the waning years of Dutch rule and early years of Japanese occupation, Salim retired from active politics and was involved in several trades. Unlike most of the future Republican leaders, Salim was never arrested nor exiled, probably owing to his vast connections with the colonial bureaucracy or his rumored services for the colonial intelligence services.

In 1943, the Japanese military government asked Salim, a renowned polyglot who spoke nine languages, to compile a military dictionary for the use of Pembela Tanah Air, the newly formed volunteer militia prepared for an impending invasion of the Allied forces. Salim found his way back to politics, being appointed to advise the Indonesian leaders (Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta, Ki Hajar Dewantara, and Mas Mansyur) who are in charge of the Pusat Tenaga Rakyat ("Center for People's Power", Putera), an intellectual body set up by Japanese government to mobilize popular support for war efforts.

Indonesian independence

editSalim was appointed to the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (Badan Penyelidik Usaha-usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia, BPUPK) in March 1945.

On 1 June, Salim was appointed to a Committee of Nine (Panitia Sembilan) tasked to draft the basis of the state. In the committee chaired by Sukarno, Salim was one of the prominent Muslim leaders alongside Wahid Hasyim and Abdul Kahar Muzakir. One of the issues that must be tackled by the committee was to find a compromise between the secular nationalist bloc, which demanded a secular state; with the Islamist bloc, which argued that being a Muslim-majority nation, an independent Indonesia should be based on Islamic principles.

The committee would end up with the Jakarta Charter, which includes Sukarno's proposed Pancasila as official state philosophy and an explicit call for Muslim Indonesians to oblige to the sharia (ketuhanan dengan kewajiban menjalankan syariat Islam bagi pemeluk-pemeluknya). BPUPK as a whole ratified it on 10 July. On 11 July, Salim was appointed to sit in the Subcommittee for Constitutional Drafting (Panitia Kecil Perancang Undang-Undang Dasar), again chaired by Sukarno. He was highly influential in the early drafting of the Constitution and was seen as a respected mediator during heated confrontations.

On 7 August, the BPUPK was dissolved and replaced with the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia, PPKI). For unclear reasons, however, Salim did not sit on the committee; he was also not recorded as being present during the independence proclamation at Sukarno's residence on 17 August.

Government and diplomatic services

editSalim did not join the first Indonesian cabinet; Sukarno, now President of the Republic, appointed him to the newly created Supreme Advisory Council (Dewan Pertimbangan Agung, DPA). He remained in that position until March 1946, when he was appointed Deputy Foreign Minister (Menteri Muda Luar Negeri) under Foreign Minister and Prime Minister Sutan Sjahrir of the Socialist Party. He reprised that role in the third Sjahrir Cabinet before being promoted to Foreign Minister in the first Amir Sjarifuddin Cabinet in July 1947; Amir, like Sjahrir, is a Socialist.

As Deputy Foreign Minister, Salim led numerous Indonesian diplomatic missions abroad. He led the Indonesian delegation at the Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi from March to April 1947. The same month, he led a small party consisting of Abdurrahman Baswedan, Rasjidi, and Nazir Sutan Pamuncak to seek diplomatic recognition from Arab states. A fluent speaker of classical (fusha) Arabic, Salim met with Mahmoud El Nokrashy Pasha, the Egyptian prime minister, and Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam, the secretary-general of the Arab League. For the next three months, Salim and his delegation successfully gained diplomatic recognition from almost all members of the League.

In August 1947, Salim with Sjahrir traveled to the United States to participate in a United Nations Security Council session in Lake Success, New York. With the help of banker Margono Djojohadikusumo (grandfather of Prabowo Subianto), the two breached the Dutch naval blockade with a plane carrying contraband vanilla to Singapore. Returning home, Salim was part of the Indonesian delegation throughout negotiations aboard USS Renville, which led to an agreement that temporarily reduced tensions after the breaking down of the previous Linggadjati Agreement. During the negotiations, Salim's friendship with the Dutch chief negotiator Abdulkadir Widjojoatmodjo (a KNIL high-ranking officer whom he had worked with in the Dutch consulate in Jeddah) helped to smoothen the process.

Salim remained in charge of foreign affairs in the first Hatta Cabinet, while officially serving ad interim. When Dutch started a military offensive called Operatie Kraai, in December 1948, he was one of the Republican leaders exiled from the capital, Yogyakarta. Alongside Sjahrir and Sukarno, Salim was first exiled to Berastagi in North Sumatera before being transferred to Parapat. With the rest of the leaders, Salim returned to Yogya and reclaimed his duties as foreign minister in the second Hatta Cabinet, having been briefly exercised by Sjafruddin Prawiranegara ex officio with his duties as Chairman of the Emergency Government of the Republic in its only cabinet from December 1948 to July 1949.

One of Salim's final diplomatic services was as part of the Indonesian delegation in the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference in The Hague in late 1949. Hatta's second cabinet was dissolved in December 1949 and the United States of Indonesia was formed. Hatta, the United States' inaugural (and only) premier and foreign minister, appointed Salim to be a special advisor on foreign affairs. The United States itself was dissolved in September 1950.

Later life and death

editAfter leaving government service, Salim returned to writing and journalism. In 1952, he was appointed to the honorary board of the Association of Indonesian Journalists (Persatuan Wartawan Indonesia, PWI). In 1953, he wrote a religious book titled Bagaimana Takdir, Tawakal, dan Tauchid Harus Dipahamkan? ("How Should Tawakkul, Taqdir, and Tawhid Be Understood?"); later editions saw it updated as Keterangan Filsafat Tentang Takdir, Tawakal, dan Tauchid ("Philosophical Addresses on Tawakkul, Taqdir, and Tawhid").

In the spring of 1953, Salim and his wife lived for six months in Ithaca, New York, where he delivered guest lectures at Cornell University. His lectures were later compiled and published as Pesan-Pesan Islam: Rangkaian Kuliah Musim Semi 1953 di Cornell University, Amerika Serikat.

Salim died on 4 November 1954, in Jakarta. He was interred at the Kalibata Heroes' Cemetery.

Personal life and legacy

editSalim married Zaenatun Nahar, a cousin, in 1912. The marriage produced eight children: Theodora Atia (Dolly); Jusuf Taufik (Totok); Violet Hanifah (Yoyet); Maria Zenobia; Achmad Sjewket; Islam Basjari; Abdul Hadi; Siti Asia; Zuchra Adiba; and Abdurrachman Ciddiq. Hadi and Adiba died as babies, while Sjewket was killed in action during the Indonesian revolution. Chalid Salim, Salim's younger brother, was a communist who became a Catholic pastor during his years of exile in Boven Digoel.[9] Emil Salim, a prominent economist and minister in the Suharto administration, is a nephew.

Dolly, the eldest, was known for being the first person to sing the lyrics of Indonesia Raya, later adopted as the republic's national anthem, during the Second Youth Congress (Kongres Pemuda II) in 1928.[10] Violet married Djohan Sjahroezah, a prominent socialist and underground anti-Japanese activist and a nephew of Sjahrir, Salim's revolutionary protege.

Salim was known for his frugality and simple lifestyle. Mohammad Roem, in a piece for Prisma magazine, described the lifestyle of the man whom he succeeded as Foreign Minister as a manifestation of leiden is lijden ("leading is suffering"), an old Dutch proverb.[11] He and his wife agreed not to send their children to Dutch colonial schools, despite being a product of the institutions; instead, they mostly homeschooled them.[12]

Informally bestowed the honorific title of the "Grand Old Man" (Kamitua yang Mulia), Salim was reported to be fluent in at least nine languages. Minangkabau and Malay would have been his native languages, followed by English, Dutch, French, Japanese, German, Latin, and Turkish. He raised his children in a multilingual household.[13] In an anecdote told by Cornell professor George McTurnan Kahin to historian Asvi Warman Adam, Salim, and South Vietnamese leader (and future president) Ngo Dinh Diem sat together in a faculty dining room at the Cornell campus. Salim stroke a conversation he soon dominated over French-educated Diem.[13]

Salim was best remembered for his sharp wit and debating skills. In a version of the story (as told by Jef Last), several Sarekat Islam members tried to mock Salim, who is in the middle of a speech, with goat sounds; alluring to Salim's white beard and in a way, his devout Islamic faith. Salim calmly responded by asking the chair "whether Sarekat has invited a herd of goats to its meeting"; and if yes, "as a polyglot I would honour their right to listen to a speech by speaking in hircine language."[13][14] In another instance, Salim was mocked by Bergmeyer, a Dutch member of the Volksraad for delivering a speech in Malay. At one point Salim had said ekonomi, the Malayized word for economy, and Bergmeyer challenged him to state the original Malay for the word. Salim quickly retorted: "if you can say what 'economy' is in the original Dutch, I'll state the Malay version for you." Both Malay and Dutch absorbed 'economy' from the Ancient Greek word of οἰκονομία, so there would be no original word in both languages.

He was also popular for his lighthearted humour. A lifelong smoker of cigar (he would sometimes lit one while teaching at Cornell[13]) a common lore was that when Salim, on behalf of the Indonesian government, met Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh[13] (some claimed, however, it's the other British royalties) during a dinner at the coronation of Elizabeth II in June 1953. A British diplomat assigned to him had asked him not to smoke his kretek in the Westminster Abbey and in the palace. During the dinner, however, Salim found the young Duke was still awkward and unsettled while greeting his guests as a new consort to the Queen. He lit his kretek and asked if the Duke knew of it. When the Duke inquired what was Salim smoking, he answered: "That, Your Highness, is the reason for which the West conquered the world!"[15]

Salim was posthumously declared a National Hero in 1960. Padang's main football stadium was named in his honor, alongside numerous roads in major Indonesian cities.[16][17]

References

edit- ^ a b Laffan, Michael F. (2003). "Between Batavia and Mecca: Images of Agoes Salim from the Leiden University Library". Archipel. 65: 109–122. doi:10.3406/arch.2003.3754. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Rizqa, Hasanul (February 23, 2019). "Masa Kecil Haji Agus Salim, 'the Grand Old Man' (2)". Republika.co.id. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Laffan, Michael Francis (2003). Islamic nationhood and colonial Indonesia : the umma below the winds. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 185–8. ISBN 9780203222577.

- ^ a b McVey, Ruth (2006). The rise of Indonesian communism (1st Equinox ed.). Equinox Publications. p. 368. ISBN 9789793780368.

- ^ "HADJI A. SALIM. Beschuldigd van spionnage". De Indische courant. April 22, 1927. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "Tegen Hadji Salim". Overzicht van de Inlandsche en Maleisisch-Chineesche pers (in Dutch). Vol. 1927, no. 22. May 28, 1927.

- ^ Rohmadi, Nazirwan; Akhyar, Muhammad (2017). "Volksraad: Malay Language (Indonesian) as a Means of Political Strategy of National Fraction". Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. 154. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Akbar, Allan (March 2013). Memata-matai Kaum Pergerakan: Dinas Intelijen Politik Hindia Belanda 1916-1934. Marjin Kiri. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-979-1260-20-6. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik. "Abang Tokoh Islam, Adik Pendeta Kristen". Tirto.id. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Sitompul, Martin (October 28, 2015). "Dolly Salim, Penyanyi Indonesia Raya Pertama di Kongres Pemuda". Historia. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik (November 4, 2017). "Memimpin Itu Menderita, Seperti Agus Salim". Tirto. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik (October 3, 2016). "Orang Terpelajar dan Homeschooling". Tirto. Tirto. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Adam, Asvi Warman. "Agus Salim, Manusia Merdeka". LIPI.go.id. Indonesian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Amar, Ady. "Debat Kusir, Belajar dari Jawaban Cerdas Agus Salim". Republika. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Toer, Pramoedya Ananta (April 18, 1999). "Best Story; The Book That Killed Colonialism". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Benda, Harry J. (1958). The Crescent and The Rising Sun. Indonesian Islam and the Japanese occupation 1942–1945. The Hague and Bandung: W. van Hoeve Ltd. p. ix. OCLC 22213896. in Kahfi 2000, p. 4

- ^ Kahfi 2000, p. 4

Bibliography

edit- Buku Peringatan, Panitia (1984). Seratus Tahun Haji Agus Salim. Jakarta: Penerbit Sinar Harapan.

- Kahfi, Erni Haryanti (2000). Haji Agus Salim : His Role in Nationalist Movements in Indonesia During the Early Twentieth Century (Master of Arts thesis). Canadian theses. Ottawa: National Library of Canada. ISBN 978-0-612-44090-6.

- Sularto, St. (2004). Haji Agus Salim (1884-1954): Tentang Perang, Jihad, dan Pluralisme. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 979-22-1094-6.