This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

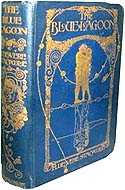

The Blue Lagoon is a coming-of-age romance novel written by Henry De Vere Stacpoole, first published by T. Fisher Unwin in 1908.[1] The Blue Lagoon explores themes of love, childhood innocence, and the conflict between civilisation and the natural world.

| |

| Author | Henry De Vere Stacpoole |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Blue Lagoon trilogy |

| Genre | Romance |

| Publisher | T. Fisher Unwin |

Publication date | 1908 |

| Publication place | Great Britain |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 328 |

| Followed by | The Garden of God |

Plot summary

editThe story centres on two cousins, Dick and Emmeline Lestrange, who are marooned with a galley cook on an island in the South Pacific Ocean following a shipwreck. The galley cook, Paddy Button, assumes responsibility for the children and teaches them how to survive, cautioning them to avoid the "arita" berries, which he calls "the never-wake-up berries".

Two and a half years after the shipwreck, Paddy dies following a drinking binge. The children survive on their resourcefulness and the bounty of their remote paradise. They live in a hut and spend their days fishing, swimming, diving for pearls, and exploring the island.

As time progresses, Dick and Emmeline undergo the natural process of maturing into young adults and develop romantic feelings for one another. Unaware of the complexities of human sexuality, they struggle to comprehend and articulate their growing physical attraction. Eventually, they engage in an intimate act, which is portrayed as resembling the courtship rituals observed in the animal kingdom.

Dick becomes attentive toward Emmeline, listening to her stories and bringing her gifts. Over several months they have sex and eventually, Emmeline becomes pregnant. The couple does not understand the physical changes happening to Emmeline's body and does not know about childbirth. When the day comes for delivery, Emmeline disappears into the forest and returns with a child. They discover over time that the baby requires a name and they call him "Hannah" because they have only ever known an infant called by that name.

Dick and Emmeline teach Hannah how to swim, fish, throw spears and play in the mud. They survive a violent tropical cyclone and other natural hazards of island life.

Back in San Francisco, Arthur, Dick's father and Emmeline's uncle and guardian, believes the two are still alive and is determined to find them, after recognizing a child's tea set belonging to Emmeline which was retrieved by a whaler on an island. Arthur finds a captain willing to take him to the island and they set out.

Meanwhile, Dick, Emmeline, and Hannah row their lifeboat to the place where they had once lived with Paddy as children. Emmeline breaks a branch off the deadly arita plant as Dick cuts bananas on the shore. While in the boat with her son, Emmeline fails to notice that Hannah has tossed one of the oars into the sea. The tide comes in and sweeps the boat into the lagoon, leaving Emmeline and Hannah stranded. As Dick swims to them, he is pursued by a shark. Emmeline strikes the shark with the remaining oar, earning Dick time to climb into the boat safely.

Although they are not far from shore, the trio cannot get back without the oars and they are unable to retrieve them from the water because of the shark. The boat is caught in the current and drifts out to sea; all the while Emmeline still grasps the arita branch.

Sometime later, Arthur's ship comes across the lifeboat and finds the three unconscious but still breathing. The arita branch is now bare save for one berry. Arthur asks, "Are they dead?" and the captain replies, "No, sir. They are asleep". The ambiguous ending leaves it uncertain whether or not they can be revived.

Characters

edit- Emmeline Lestrange: a shipwrecked orphan, the heroine

- Dick Lestrange: Emmeline's cousin, a shipwrecked orphan, the hero

- Paddy Button: the galley cook of the wrecked ship

- Arthur Lestrange: Dick's father and Emmeline's uncle

- Hannah: Dick and Emmeline's son

History

editEarly in 1907, lying awake and pondering, not for the first time in my life, on the extraordinary world we live in, the idea came to me of what it must have been like to the cave men who had no language and for whom a sunset had no name tacked on to it, a storm no name, Life no name, death no name and birth no name, and the idea came to me of two children, knowing nothing about any of these things, finding themselves alone on a desert island facing these nameless wonders.

Henry De Vere Stacpoole, Men and Mice (1942)[2]

During a sleepless night, Stacpoole's mind wandered to the concept of a caveman's life. He found himself in awe of the primitive man's ability to appreciate and find wonder in the most basic of things, such as a sunset or thunderstorm. He compared this to the current era, where advanced technology has taken away the mystery and enchantment of these natural occurrences. Modern-day humans have become so consumed with the scientific explanation of things that they have lost the ability to appreciate the beauty and awe-inspiring qualities of nature. By doing so, they have deprived themselves of the simple joys that once filled them with wonder.[3][4]: 210

Stacpoole, being a seasoned medical practitioner, had encountered instances of birth and death, and as a result, these occurrences no longer possessed any sense of awe or enigma for him. This led him to ponder the concept of two young children who are forced to grow up on an isolated island with no access to any form of guidance or knowledge. These children would be subject to the natural phenomena of birth, death, and storms, and would have to experience the highs and lows of life without any assistance. Stacpoole found this idea fascinating and was inspired to explore it further. [5] The next day, he began to work on The Blue Lagoon.[6]

Comparisons with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

editThe author deliberately draws parallels between The Blue Lagoon and the Biblical story of Adam and Eve, highlighting the innocence and naivety of the two young protagonists, Emmeline and Dick. However, it is evident that the author is also influenced by Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. The narrative structure of childhood leading to adolescent romance in Stacpoole's novel is likely influenced by Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe and Bernardin de St. Pierre's Paul et Virginie.[4]: 210 The reference to Wonderland is made when the castaways approach Palm Tree Island, which is the beginning of an adventure that is full of similarities to Alice's journey. Like Alice, Emmeline is around the same age, and their innocent curiosity leads them to explore their surroundings. Emmeline's tea party on the beach and her former pet's resemblance to the Cheshire Cat are examples of the author's allusions to Carroll's work.[6]

The similarities continue with Emmeline's innocent attempt to eat the "never-wake-up berries" and receiving a lecture on poison from Paddy Button, which is reminiscent of Alice's encounter with the "Drink Me" bottle. The "Poetry of Learning" chapter also draws parallels with Alice's conversation with the Caterpillar. Paddy's smoking of a pipe and the children teaching him to write his name in the sand echoes the Caterpillar smoking a hookah while questioning Alice's identity.[6]

The author also incorporates other references to wonder, curiosity, and strangeness throughout the novel, honouring Carroll's work. The children lose track of time, similar to the Mad Hatter's tea party, and undergo physical changes, like Alice growing taller and Emmeline becoming plumper. The reference to the baby in "Pig and Pepper" is also made when Hannah sneezes at the sight of Dicky.[6]

Reception

editUpon its initial publication, the book gained popularity.[6] The critical acclaim was substantial, with the Times Literary Supplement commending the book's tale of discovering love and experiencing innocent mating, describing it as refreshing as the ozone that had strengthened the characters.[7][8] The Saturday Review highlighted the novel's ability to captivate readers, its carefully constructed premise, the characters' growth from childhood innocence to self-sufficiency, and the enchanting love story. The reviewer acknowledged some grammatical issues but commended the author's imaginative storytelling, and went so far as to assert that the label of "romance," frequently used in contemporary works, was genuinely fitting for this novel.[9]

The Athenaeum's review highlighted the poetic and imaginative qualities of the story, which revolves around two children stranded on a desert island with an elderly Irish sailor, Paddy Button. The review praised the story's charm and emotional depth, particularly in the early chapters depicting the children's adventures with Paddy. It commended the portrayal of their growth, learning about love and life through their natural surroundings. Although the review noted the eventual rescue and return to civilization, it underscored that the most attractive aspects of the novel lie in the initial chapters and the endearing character of Paddy Button.[10]

The Academy gave a positive review and commended Stacpoole for his treatment of delicate themes and the character development of the two children. It also noted the book's engaging plot and the richness of the island's descriptions, though it did have reservations about the ending.[11]

The Sydney Morning Herald praised Stacpoole's handling of a challenging subject matter, as well as his keen eye, accurate psychology, and "quite adequate literary skill".[12]

The work was acclaimed by the Review of Reviews for its uniqueness, described as a narrative that diverges from any other published story. Additionally, Stacpoole was praised for his authorship of an authentic, delightful, and uncomplicated romance, showcasing the author's boldness and creativity.[13]

The novel received acclaim from the South Australian Register, which described it as an exemplary maritime narrative suitable for both male and female juvenile readers. The Register also commended it for its abundance of educational insights and profound emotions that can only arise from a life of being alone and removed from society.[14]

The novel, as reviewed by The Japan Weekly Mail, has been described as a "moderately good tale", encompassing numerous startling incidents. However, they cautioned that the conclusion of the novel may leave readers feeling emotionally detached, as it was deemed unsatisfactory.[15]

Punch particularly praised the novel for Stacpoole's "powerful" writing and for being "fascinating," "delicately conceived," and "healthily nurtured on the fruits of an observation which knows when not to observe," but warned that the novel "has the power of the rapier rather than that of the bludgeon, which... is the kind of force that epithet has come latterly to suggest when applied to fiction."[16]

The New York Sun praised the novel for being "told prettily enough" and "provoking to have a situation carefully prepared", but warned that "the author [Henry De Vere Stacpoole] is so carried away by the machinery he devises that he seems inclined to pass over the poetry in a hurry."[17]

Frederic Taber Cooper of The Bookman offered a nuanced assessment of the book. While acknowledging that the novel deviated from conventional literary standards in terms of construction, Cooper commended it for its successful attempt to explore the complex and unusual theme of two individuals growing up in a state of nature without guidance. He noted the book's similarity to a short story by Morgan Robertson and highlighted the careful insight into the psychology of the characters as they navigate existence unaided. However, Cooper critiqued the book's narrative mechanism, particularly in the final episode where the father encounters his child by sheer chance, finding it jarring and lacking in credibility. Despite its shortcomings in storytelling, The Blue Lagoon is recognized for its daring exploration of this unique theme.[18]

The New York Times praised Stacpoole's novel for its examination of the dilemma surrounding the solitary development of two children on the island after surviving a shipwreck. The newspaper did issue a warning, however, suggesting that those with traditional and rigid beliefs might continue to hold out hope that a missionary would soon arrive on the island carrying religious items. Nevertheless, it is specified that the island is devoid of any missionary inhabitants.[19]

The novel was reprinted over twenty times in the following twelve years.[6]

Louis J. McQuilland of The Bookman wrote in 1921:

It is probable that The Blue Lagoon will always be the most favoured of Stacpoole's books because its appeal is universal. It is an idyll of childhood and youth amid tropical splendours which catch the heart by their beauty. The theme of Dick and Emmeline growing up together and gradually awakening to passion is a very delicate one. No one but a writer of the finest sensibility could have dealt with the stirring of innocence to knowledge without creating a sense of awkwardness and embarrassment in all those who reverence the spirituality of youth. That extremely sickly romance, Paul and Virginia, had a European vogue for generations. It is to The Blue Lagoon as a bit of coloured glass to a great emerald.[20]

Claud Cockburn wrote in 1972 that the novel "almost perfectly exemplifies what readers wanted, and for that matter still want, from the Pacific Island novel."[21]

Robert Hardin wrote in 1996:

The sheer bulk of natural description in the novel tends to push aside the narrative, further undercutting the reader's sense of time. Conventions of romance like the mysterious idol and the threat of the savages (complete with drums and secretly observed human sacrifice) lend a necessary minimum of fear and excitement to the story, but even less than in Daphnis and Chloe. Instead, the story fixes attention on the maturing of a couple, not of two separate characters. Seen as an idyllic romance, Blue Lagoon almost has to end at that point, if only because the couple's return to society with a child would have raised some complicated questions.[4]: 211

Peter Keating noted that around 1905, the rise of the "sex novel" or "sex problem" novel became prominent, with The Blue Lagoon identified as a "sensationally erotic" example, alongside Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks (1907). Keating called it “the ultimate sex novel,” reflecting an idealisation of natural sexuality against a backdrop of modern moral decay.[22] Stacpoole’s work serves as a bridge between the absence of sexual themes in Victorian literature and their prevalence in authors like D. H. Lawrence. Malcolm Muggeridge even considered Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928) a "lineal descendant" of The Blue Lagoon.[23]

Adaptations

editStage

edit- The Blue Lagoon (opened 28 August 1920) produced by Basil Dean. The adaptation was by Norman MacOwan and Charlton Mann.[6][24]

Films

editSix films have been based on this novel:

- The Blue Lagoon (1923), a silent film directed by William Weston Bowden and Dick Cruickshanks, starring Molly Adair and Arthur Pusey; produced for African Film Productions (lost)

- The Blue Lagoon (1949), directed by Frank Launder, starring Jean Simmons and Donald Houston; currently owned by ITV Studios through The Rank Organisation film library

- The Blue Lagoon (1980), directed by Randal Kleiser, starring Brooke Shields and Christopher Atkins; released by Columbia Pictures

- Pengantin Pantai Biru (1983), an Indonesian adaptation directed by Wim Umboh, starring Meriam Bellina and Sandro Tobing

- Return to the Blue Lagoon (1991), directed by William A. Graham, starring Brian Krause and Milla Jovovich; released by Columbia Pictures, sequel to the 1980 adaptation

- Blue Lagoon: The Awakening (2012); produced by Sony Pictures Television for Lifetime

Sequels

editFollowing the triumph of The Blue Lagoon, Stacpoole wrote two sequels:

- The Garden of God (1923)

- The Gates of Morning (1925)

Copyright status

editIn Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, the novel's copyright expired on 1 January 2002. In its country of origin, the copyright expired on 1 January 2022.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Stacpoole, Henry de Vere (1908). The Blue Lagoon. T. Fisher Unwin.

- ^ Stacpoole, Henry De Vere (1942). Men and Mice: 1863-1942. London: Hutchinson. p. 93.

- ^ Gale 1995, p. 282.

- ^ a b c Hardin, Richard (1996). "The Man Who Wrote "The Blue Lagoon"". English Literature in Transition (1880-1920). 39 (2). ISSN 0013-8339.

- ^ Gale 1995, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gale 1995, p. 283.

- ^ Kemp, Sandra; Mitchell, Charlotte; Trotter, David (1997). Edwardian fiction: an Oxford companion. Oxford New York: Oxford university press. p. 36. ISBN 0198117604.

- ^ Stacpoole, H. De Vere; Gavin, Adrienne E. (2010). The blue lagoon: a romance. Valancourt classics (1st ed.). Kansas City: Valancourt Books. pp. xx. ISBN 978-1-934555-72-9.

- ^ "Novels". Saturday Review. Vol. 105, no. 2727. 1 February 1908. p. 146.

- ^ "New novels". The Athenaeum. No. 4189. 8 February 1908. p. 155.

- ^ "Fiction". The Academy. Vol. 74, no. 1869. 29 February 1908. p. 518.

- ^ "The Importunate Novelist". Sydney Morning Herald. No. 21920. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. 18 April 1908. p. 4. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "The Review's Bookshop". The Review of Reviews. Vol. 37, no. 218. February 1908. p. 215. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Two young islanders". The Register. No. 19143. 21 March 1908. p. 13. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "The Bookshelf". The Japan Weekly Mail. Vol. 69, no. 13. 28 March 1908. p. 360.

- ^ "Our booking office". Punch. Vol. 134. 19 February 1908. p. 144.

- ^ "Fiction of the season". The Sun. Vol. 75, no. 280. New York, New York, United States. 6 June 1908. p. 7.

- ^ Cooper, Frederic Taber (August 1908). "Function of fiction and recent novels". The Bookman. Vol. 27, no. 6. Open Court Publishing Co. p. 579. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Best Books for Summer Reading". The New York Times Saturday Review of Books. No. 13 June 1908. The New York Times Company. pp. 343–344.

- ^ McQuilland, Louis J. (June 1921). "H. De Vere Stacpoole". The Bookman. Vol. 60, no. 357. Hodder And Stoughton Ltd Mill Rd. pp. 126–127. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Cockburn, Claud (1972). Bestseller: the books that everyone read; 1900-1939. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. p. 67. ISBN 0283978481.

- ^ Keating, P. J. (1989). "Parents and Children". The haunted study: a social history of the English novel, 1875-1914. Vol. 2: Changing Times. London: Secker & Warburg. pp. 208–210. ISBN 978-0-436-23248-0.

- ^ Muggeridge, Malcolm (15 May 1966). "Reading for the Raj". The Observer. p. 90.

- ^ "The Playhouses". The Illustrated London News. 157 (4246). Illustrated London News: 378. 4 September 1920. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

References

edit- Malone, Edward (1995). "Henry De Vere Stacpoole". Late-Victorian and Edwardian British novelists. Vol. 153. Detroit, Michigan, United States: Gale Research Inc. pp. 278–287. ISBN 9780810357143.

External links

edit- The Blue Lagoon at Standard Ebooks

- The Blue Lagoon at Project Gutenberg

- The Blue Lagoon public domain audiobook at LibriVox