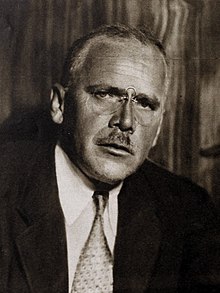

Hans von Kaltenborn (July 9, 1878 – June 14, 1965), generally known as H. V. Kaltenborn, was an American radio commentator. He was heard regularly on the radio for over 30 years, beginning with CBS in 1928. He was known for his precise diction, ability to ad-lib and his depth of knowledge of world affairs.

H. V. Kaltenborn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hans von Kaltenborn July 9, 1878 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | June 14, 1965 (aged 86) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | Harvard University |

| Occupation(s) | Radio broadcaster, news anchor |

| Spouse |

Olga von Nordenflycht

(m. 1910) |

| Children | 2 |

Early life

editKaltenborn was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and grew up in Merrill, Wisconsin. He began his career as a newspaper reporter, and moved to radio when it began to establish itself as a bona fide source of news.

When he was 19, he ran away from home and joined the 4th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment[1] to fight in the Spanish–American War. The war ended two months after his enlistment before the regiment could go overseas. From training camp Kaltenborn wrote articles for the Merrill Advocate, becoming editor of the paper following his demobilisation.[2]

He left the Advocate to spend time in Europe. He returned to take a job with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. At 24, he went to college, enrolling as a special student at Harvard University. When he finished, he returned to the Eagle, traveling during summers to distant locales.

Anti-German sentiment during World War I motivated Kaltenborn to change his byline from Hans von Kaltenborn to H. V. Kaltenborn.[3] He was no relation to General Hans von Kaltenborn-Stachau,[4] a former Prussian Minister of War.

Early radio

editCalled the "Dean" of radio commentators by Edward R. Murrow and others,[5] Kaltenborn addressed the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce while speaking from an experimental station in Newark, N.J. on April 21, 1921 where the group had assembled there to see the newly invented radio. On April 4, 1922, he made the first of what later became a regular series of radio talks on current events. Kaltenborn called them the "first spoken editorials ever heard by a radio audience."[6]

CBS

editKaltenborn was one of the first news readers to provide analysis and insight into current news stories. His vast knowledge of foreign affairs and international politics amply equipped him for covering crises in Europe and the Far East in the 1930s. His vivid reporting of the Spanish Civil War and the Czech crisis of 1938 helped establish the credibility of radio news in the public mind and helped to overcome the nation's isolationist sensibilities. As authors Christopher H. Sterling and John M. Kittross wrote,[citation needed] Kaltenborn reported on the Spanish Civil War "while hiding in a haystack between the two armies. Listeners in America could hear bullets hitting the hay above him while he spoke."

Radio historian James F. Widner described Kaltenborn's skill as a news analyst:

Kaltenborn was known as a commentator who never read from a script. His "talks" were extemporaneous[ly] created from notes he had previously written. His analysis was welcome[d] into homes especially during the war and the time leading up to America's entry into it. He had an international reputation and was able to speak intelligently about events because he had interviewed many of those involved. From the contacts he developed in his travels and his ability to speak fluent German and French, Kaltenborn seemed chosen for the role he developed at CBS. One of his most famous periods was during the Munich crisis in 1938. Much of what listeners heard was Kaltenborn speaking without script even after sometimes having been up for most of a night covering the breaking news. Some claimed that when Kaltenborn was awakened during the Munich vigil, one merely had to utter Munich and Kaltenborn could talk for hours on the subject.[6]

When CBS broadcast Hitler's address to the 1938 Nuremberg rally, Kaltenborn provided simultaneous translation for the two-hour speech, which was the first time many Americans had heard Hitler's "fury and hatred" for themselves.[7]

NBC

editKaltenborn joined NBC in 1940. On election night in 1948, he and Bob Trout, a former CBS colleague, were at the NBC news desk to broadcast the returns of the White House race between President Harry S. Truman and challenger Thomas E. Dewey. Throughout the evening, the returns were too close to call. As the evening progressed, Kaltenborn could see a swing in Dewey's favor. It was enough for him to project Dewey the winner, although the returns were still close. What Kaltenborn did not foresee was another swing in the votes going to Truman. As evening turned to early morning, Kaltenborn retracted his original projection and announced Truman as the winner.

On his newscast, Kaltenborn described how Truman did an impersonation of the journalist describing how he (Truman) was losing the election. Kaltenborn later stated, "We can all be human with Truman. Beware of that man in power who has no sense of humor".

Another incident of embarrassment came when Dizzy Dean was Kaltenborn's guest on the program. Exasperated by Dean mispronouncing his name — various sources[which?] say "Cattlinbomb", "Cottonborn", etc. — Kaltenborn decided to throw the pitcher a curve and asked him what he would do about Russia. Dean didn't miss a beat. He said, "I'd take some bats and balls and gloves and sneak them behind the Iron Curtain and teach them Rooshin kids how to play baseball. Why if Joe Stallion knowed how much money there was in concessions, he'd get out of politics and into an honest business".

Though Kaltenborn left full-time broadcasting in 1953, he provided analyses during NBC's television coverage of the Republican and Democratic conventions in 1956. Those live newscasts were anchored by Chet Huntley and David Brinkley in their first on-air pairing. Kaltenborn was in his mid-seventies when the television age arrived, and some[who?] see his time in TV as a disappointment. Forever the radio newsman, Kaltenborn would report everything, including the movements of the subject he was describing, despite the fact that millions of people were watching it.

Kaltenborn was also a regular panelist on the NBC television series Who Said That?, in which a panel of celebrities attempt to determine the speaker of a quotation from recent news reports.

Kaltenborn had very specific views about radio's role in presenting the news. Later in life he wrote on the subject in many of his books. He was one of four journalists who portrayed themselves in the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still. Kaltenborn also appears as himself in the 1939 Frank Capra film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

Accolades

editIn 1944 Kaltenborn received the Alfred I. duPont Award.[8] The National Radio Hall of Fame inducted Kaltenborn in 2011.

Personal life

editReturning to the United States in January 1908, Kaltenborn met the 20-year-old Olga von Nordenflycht, the American-born daughter of the German Consul General based in Chicago. Their shipboard romance became a long-distance courtship. He realised that Olga, who was also a linguist and writer who loved travel, was the woman for him. Following his graduation from Harvard and rejoining The Brooklyn Eagle, the couple returned to Berlin in 1910 for their marriage and a honeymoon tour of Europe. Hans and Olga remained married until he died 55 years later in 1965.

The couple had two children, daughter Olga Anaïs (1911–1980) and son Rolf (1915–1995).[9][10] They had seven grandchildren and six great grandchildren. His widow Olga died in 1977 at age 88.[4]

Filmography

edit| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington | Himself | |

| 1948 | The Babe Ruth Story | ||

| 1951 | The Day the Earth Stood Still | Uncredited (final film role) |

Kaltenborn also provided "The Voice of Tomorrow" at the 1939 New York World's Fair.[5]

Notes

edit- ^ "4th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry". www.spanamwar.com.

- ^ Finkelstein, David (February 2010). "Radio Journalism: H. V. Kaltenborn and José Pardo Llada". Journalism Practice. 4 (1): 114–118. doi:10.1080/17512780903416891. S2CID 144152794.

- ^ Bliss, Edward, Jr. (2010). Now the News: The Story of Broadcast Journalism. Columbia University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780231521932.

- ^ a b Ramsburg, Jim. "H. V. Kaltenborn (Audio)". GOld Time Radio.

- ^ a b Nimmo, Dan D. & Newsome, Chevelle (1997). Political Commentators in the United States in the 20th Century: A Bio-critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 129.

- ^ a b "Radio Days - H. V. Kaltenborn". www.otr.com.

- ^ Allhoff, Fred; Miller, Terry (1979). Lightning in the Night. Introduction by Terry Miller. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-13-536557-1. LCCN 78023538.

- ^ "All duPont–Columbia Award Winners". Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Archived from the original on 2012-08-14. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ Lowery, Fred (September 26, 1995). "Rolf Kaltenborn, Arts Contributor". South Florida Sun Sentinel.

- ^ "Rolf Kaltenborn, son of H.V. Kaltenborn, radio news commentator, who..." Getty Images.

References

edit- Cox, Jim (2007). Radio Speakers: Narrators, News Junkies, Sports Jockeys, Tattletales, Tipsters, Toastmasters and Coffee Klatch Couples Who Verbalized the Jargon of the Aural Ether from the 1920s to the 1980s—A Biographical Dictionary. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company.

- Kolb, James Sylvester. H.V. Kaltenborn: An Analysis of His Thought and His Career. Madison: University of Wisconsin.