The Hare Indian dog is an extinct domesticated canine; possibly a breed of domestic dog, coydog, or domesticated coyote; formerly found and originally bred in northern Canada by the Hare Indians for coursing. It had the speed and some characteristics of the coyote, and the domesticated temperament and other characteristics of a domestic dog. It gradually lost its usefulness as aboriginal hunting methods declined, and became extinct or lost its separate identity through interbreeding with dogs in the 19th century, though some claim the breed still exists in modified form.

| Hare Indian dog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Other names | Mackenzie River dog Trap line dog[1] C. familiaris lagopus (obsolete) |

| Origin |

|

| Breed status | Extinct |

| Dog (domestic dog) | |

Appearance

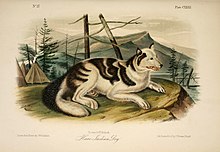

editThe Hare Indian dog was a diminutive, slenderly built domesticated canid with a small head[2] and a narrow, pointed and elongated muzzle.[3] Its pointed ears were erect and broad at the base, and closer together than those of the Canadian Eskimo dog.[2] Its legs were slender and rather long. The tail was thick and bushy,[3] and it curled upwards over its right hip,[2] though not to the extent of the Canadian Eskimo dog. The fur was long and straight, the base colour being white with large, irregular greyish black patches intermingled with various brown shades. The outside of the ears was covered with short brown hair which darkened at the base. The fur in the inside of the ears was long and white. The fur of the muzzle was short and white, as with the legs, though it became longer and thicker at the feet.[3] Black patches were present around the eyes. Like the wolves with which it was sympatric, it had long hair between its toes, which projected over the soles, with naked, callous protuberances being present at the root of the toes and soles, even in winter. In size, it was intermediate to the coyote and the American red fox.[2]

Temperament

editThe Hare Indian dog was apparently very playful, and readily befriended strangers,[3] though it was not very docile, and disliked confinement of any kind. It apparently expressed affection by rubbing its back against people, similar to a cat.[2] In its native homeland, it was not known to bark, though puppies born in Europe learned how to imitate the barking of other dogs.[3] When hurt or afraid, it howled like a wolf, and when curious, it made a sound described as a growl building up to a howl.[2]

The Hare-Indian Dog is very playful, has an affectionate disposition, and is soon gained by kindness. It is not, however, very docile, and dislikes confinement of every kind. It is very fond of being caressed, rubs its back against the hand like a cat, and soon makes an acquaintance with a stranger. Like a wild animal it is very mindful of an injury, nor does it, like a spaniel, crouch under the lash; but if it is conscious of having deserved punishment, it will hover round the tent of its master the whole day, without coming within his reach, even if he calls it. Its howl, when hurt or afraid, is that of the wolf; but when it sees any unusual object it makes a singular attempt at barking, commencing by a kind of growl, which is not, however, unpleasant, and ending in a prolonged howl. Its voice is very much like that of the prairie wolf [coyote]. The larger Dogs which we had for draught at Fort Franklin, and which were of the mongrel breed in common use at the fur posts, used to pursue the Hare-Indian Dogs for the purpose of devouring them; but the latter far outstripped them in speed, and easily made their escape. A young puppy, which I purchased from the Hare Indians, became greatly attached to me, and when about seven months old ran on the snow by the side of my sledge for nine hundred miles, without suffering from fatigue. During this march it frequently of its own accord carried a small twig or one of my mittens for a mile or two; but although very gentle in its manners it showed little aptitude in learning any of the arts which the Newfoundland Dogs so speedily acquire, of fetching and carrying when ordered. This Dog was killed and eaten by an Indian, on the Saskatchewan, who pretended that he mistook it for a fox. The most extraordinary circumstance in this relation is the great endurance of the puppy, which certainly deserves special notice. Even the oldest and strongest Dogs are generally incapable of so long a journey as nine hundred miles (with probably but little food), without suffering from fatigue.

— Sir John Richardson, Fauna Boreali-Americana, 1829, p. 79

History

editIt is thought by one writer that the breed originated from a cross between native Tahltan bear dogs and dogs brought to the North American continent by Viking explorers, as it bears strong similarities to Icelandic breeds in appearance and behavior. Sir J. Richardson of Edinburgh, on the other hand, who studied the breed in the 1820s, in their original form before being diluted by crossings with other breeds, could detect no decided difference in form between this breed and a coyote, and surmised that it was a domesticated version of the wild animal. He wrote, "The Hare Indian or Mackenzie River Dog bears the same relation to the prairie wolf [coyote] as the Esquimeaux Dog [Malamute] does to the great grey wolf."[4] The breed seemed to be kept exclusively by the Hare Indians and other neighboring tribes, such as the Bear, Mountain, Dogrib, Cree, Slavey and Chippewa tribes living in the northwestern territories of Canada and the United States around the Great Bear Lake, Southwest to Lake Winnipeg and Lake Superior and West to the Mackenzie River.[1] They were valued by the Indians as coursorial hunters, and they subsisted almost entirely on the produce of each hunt. Although not large enough to pose a danger to the moose and reindeer they hunted, their small size and broad feet allowed them to pursue large ungulates in deep snow, keeping them at bay until the hunters arrived.[3] It was too small to be used as a beast of burden.[2] It was the general belief among the Indians that the dog's origin was connected to the Arctic fox.[5] When first examined by European biologists, the Hare Indian dog was found to be almost identical to the coyote in build (save for the former's smaller skull) and fur length. The first Hare Indian dogs to be taken to Europe were a pair presented to the Zoological Society of London, after Sir John Richardson's and John Franklin's Coppermine Expedition of 1819–1822. Though originally spread over most of the northern regions of North America, the breed fell into decline after the movement of First Nations onto reserves and the decline of available wild game limited the ability of First Nations to hunt. It gradually intermingled with other breeds such as the Newfoundland dog, the Canadian Eskimo dog and mongrels.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Hare Indian dogs". Song Dog Kennels. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fauna Boreali-americana, Or, The Zoology of the Northern Parts of British America: Containing Descriptions of the Objects of Natural History Collected on the Late Northern Land Expeditions, Under Command of Captain Sir John Franklin, R.N. By John Richardson, William Swainson, William Kirby, published by J. Murray, 1829.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoological Society, Published, with the Sanction of the Council, Under the Superintendence of the Secretary and Vice-secretary of the Society, by Edward Turner Bennett, Zoological Society of London, William Harvey, Illustrated by John Jackson, William Harvey, G. B., S. S., Thomas Williams, Robert Edward Branston, George Thomas Wright. Published by Printed by C. Whittingham, 1830.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 9th edition, 1875, in the 1891 Peale reprint, Chicago, Vol. VII p. 324, under the article "dog."

- ^ Rural sports by WM. B. Daniel, Vol. 1, 1801.