Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince is a fantasy novel written by the British author J. K. Rowling. It is the sixth novel in the Harry Potter series, and takes place during Harry Potter's sixth year at the wizard school Hogwarts. The novel reveals events from the early life of Lord Voldemort, and chronicles Harry's preparations for the final battle against him.

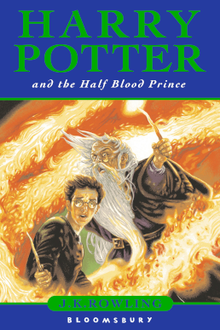

Cover art of the first UK edition | |

| Author | J. K. Rowling |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Jason Cockcroft (first edition) |

| Language | English |

| Series | Harry Potter |

Release number | 6th in series |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Bloomsbury (UK) |

Publication date | 16 July 2005 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 607 (first edition) |

| ISBN | 0-7475-8108-8 |

| 823.914 | |

| Preceded by | Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix |

| Followed by | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows |

The book was published in the United Kingdom by Bloomsbury and in the United States by Scholastic on 16 July 2005, as well as in several other countries. It sold almost seven million copies in the first 24 hours after its release,[1] a record eventually broken by its sequel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[2] There were many controversies before and after it was published, including the right-to-read copies delivered before the release date in Canada. Reception to the novel was generally positive, and it won several awards and honours, including the 2006 British Book of the Year award.

Reviewers noted that the book had a darker tone than its predecessors, though it did contain some humour. Some considered the main themes love, death, trust, and redemption. The considerable character development of Harry and many other teenage characters also drew attention.

Plot

editAfter his fifth year at Hogwarts, Harry has spent two weeks mourning the loss of his godfather, Sirius Black. As Albus Dumbledore escorts him to the Weasley home, they visit the retired Hogwarts professor Horace Slughorn, who agrees to resume teaching. Meanwhile, Bellatrix Lestrange and her sister Narcissa Malfoy convince Severus Snape to make an Unbreakable Vow to protect Narcissa's son Draco at Hogwarts.

While out shopping for school supplies, Harry, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger observe Draco making inquiries at Borgin and Burkes, a shop known for its connection to the Dark Arts. At Hogwarts, the students learn that Slughorn will be teaching Potions, while Snape will be taking over Defence Against the Dark Arts. For Slughorn's first class, Harry and Ron borrow a pair of old textbooks. Harry's textbook previously belonged to someone known as "The Half-Blood Prince", and it contains many helpful tips. Following the instructions of the Prince, Harry becomes an expert potion brewer. He rises to the top of the class and wins a vial of the luck potion Felix Felicis.

Dumbledore prepares Harry for his eventual battle with Voldemort by educating him about Voldemort's past as Tom Riddle. While a student at Hogwarts, Riddle had asked Slughorn about objects called Horcruxes, which can grant immortality by encasing fragments of a wizard's soul. Dumbledore wants to see the memory as it appears in Slughorn's mind, and asks Harry to retrieve it from him. Harry joins the Slug Club, a group of Slughorn's famous, talented and well-connected students. Hermione and Ginny also attend the club, which causes Ron to feel left out. He accepts an invitation from Hermione to Slughorn's Christmas party, but upsets her when he kisses Lavender Brown. Meanwhile, Harry develops a crush on Ginny.

When Ron is poisoned and admitted to the infirmary, Hermione visits him, which brings an abrupt end to his relationship with Lavender. Harry discards his Potions textbook after he nearly kills Draco with one of the Prince's scribbled spells. Later, Harry's luck potion helps him obtain Slughorn's memory and causes Ginny to break up with her boyfriend Dean Thomas, which allows Harry to start seeing her instead. Slughorn's memory suggests that Voldemort created six Horcruxes, though Dumbledore explains that two are already destroyed. He asks Harry to accompany him to retrieve another.

In a remote cave, Harry and Dumbledore overcome many obstacles before seizing the Horcrux. Back at Hogwarts, Dumbledore unexpectedly immobilizes Harry under his invisibility cloak. A group of Death Eaters arrives with Draco, who falters in an attempt to kill Dumbledore. Snape then casts the killing curse on Dumbledore and sends him falling to his death. Harry tries to fight Snape as he flees, but is overpowered. Snape reveals himself as the Half-Blood Prince and brags about creating the spells Harry is using. After Snape escapes, Harry discovers that the Horcrux he obtained is fake. He resolves to find and destroy all the remaining Horcruxes, and Ron and Hermione pledge to join him.

Development

editSeries

editHarry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince is the sixth novel in the Harry Potter series.[3] The first novel, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was originally published by Bloomsbury in 1997. Philosopher's Stone was followed by Chamber of Secrets (1998), Prisoner of Azkaban (1999), Goblet of Fire (2000), and Order of the Phoenix (2003).[a] Half-Blood Prince was followed by the final novel in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Half-Blood Prince sold 9 million copies in the first 24 hours of its worldwide release.[b]

Background

editRowling stated that she had Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince "planned for years," but she spent two months revisiting her plan before she began writing the story's first draft. This was a lesson learned after she did not check the plan for Goblet of Fire and had to rewrite an entire third of the book.[16] She started writing the book before her second child, David, was born, but she took a break to care for him.[17] The first chapter, "The Other Minister", which features meetings between the Muggle Prime Minister, Minister for Magic Cornelius Fudge, and his successor, Rufus Scrimgeour, was a concept Rowling tried to start in Philosopher's Stone, Prisoner of Azkaban, and Order of the Phoenix, but she found "it finally works" in Half-Blood Prince.[18] She stated that she was "seriously upset" writing the end of the book, although Goblet of Fire was the hardest to write.[19] When asked if she liked the book, she responded, "I like it better than I liked Goblet, Phoenix or Chamber when I finished them. Book six does what I wanted it to do and even if nobody else likes it (and some won't), I know it will remain one of my favourites of the series. Ultimately you have to please yourself before you please anyone else!"[20]

Rowling revealed the title of Half-Blood Prince on her website on 24 June 2004.[21] This was the title she had once considered for the second book, Chamber of Secrets, though she decided the information disclosed belonged later on in the story.[22] On 21 December 2004, she announced she had finished writing it, along with the release date of 16 July.[23][24] Bloomsbury unveiled the cover on 8 March 2005.[25]

Controversies

editThe record-breaking publication of Half-Blood Prince was accompanied by controversy. In May 2005, bookmakers in the UK suspended bets on which main character would die in the book amid fears of insider knowledge. A number of high-value bets were made on the death of Albus Dumbledore, many coming from the town of Bungay where it was believed the books were being printed at the time. Betting was later reopened.[26] Additionally, in response to Greenpeace's campaign on using forest-friendly paper for big-name authors, Bloomsbury published the book on 30% recycled paper.[27]

Right-to-read controversy

editIn early July 2005, a Real Canadian Superstore in Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada, accidentally sold fourteen copies of The Half-Blood Prince before the authorised release date. The Canadian publisher, Raincoast Books, obtained an injunction from the Supreme Court of British Columbia that prohibited the purchasers from reading the books before the official release date or discussing the contents.[28] Purchasers were offered Harry Potter T-shirts and autographed copies of the book if they returned their copies before 16 July.[28]

On 15 July, less than twelve hours before the book went on sale in the Eastern time zone, Raincoast warned The Globe and Mail newspaper that publishing a review from a Canada-based writer at midnight, as the paper had promised, would be seen as a violation of the trade secret injunction. The injunction sparked a number of news articles alleging that the injunction had restricted fundamental rights. Canadian law professor Michael Geist posted commentary on his blog.[29] Richard Stallman called for a boycott and requested the publisher issue an apology.[30] The Globe and Mail published a review from two UK-based writers in its 16 July edition and posted the Canadian writer's review on its website at 9:00 that morning.[31] Commentary was also provided on the Raincoast website.[32]

Style and themes

editSome reviewers noted that Half-Blood Prince contained a darker tone than the previous Potter novels. The Christian Science Monitor's reviewer Yvonne Zipp argued the first half contained a lighter tone to soften the unhappy ending.[33] The Boston Globe reviewer Liz Rosenberg wrote, "lightness [is] slimmer than ever in this darkening series...[there is] a new charge of gloom and darkness. I felt depressed by the time I was two-thirds of the way through." She also compared the setting to Charles Dickens's depictions of London as it was "brooding, broken, gold-lit, as living a character as any other."[34] Christopher Paolini called the darker tone "disquieting" because it was so different from the earlier books.[35] Liesl Schillinger, a contributor to The New York Times book review, also noted that Half-Blood Prince was "far darker" but "leavened with humor, romance and snappy dialogue." She suggested a connection to the 11 September attacks, as the later, darker novels were written after that event.[36] David Kipen, a critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, considered the "darkness as a sign of our paranoid times" and singled out curfews and searches that were part of the tightened security at Hogwarts as resemblances to our world.[37]

Julia Keller, a critic for the Chicago Tribune, highlighted the humour found in the novel and claimed it to be the success of the Harry Potter saga. She acknowledged that "the books are dark and scary in places" but "no darkness in Half-Blood Prince...is so immense that it cannot be rescued by a snicker or a smirk." She considered that Rowling was suggesting difficult times can be worked through with imagination, hope, and humour and compared this concept to works such as Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time and Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows.[38]

Rosenberg wrote that the two main themes of Half-Blood Prince were love and death and praised Rowling's "affirmation of their central position in human lives." She considered love to be represented in several forms: the love of parent to child, teacher to student, and the romances that developed between the main characters.[34] Zipp noted trust and redemption to be themes promising to continue in the final book, which she thought "would add a greater layer of nuance and complexity to some characters who could sorely use it."[33] Deepti Hajela also pointed out Harry's character development, that he was "no longer a boy wizard; he's a young man, determined to seek out and face a young man's challenges."[39] Paolini had similar views, claiming, "the children have changed...they act like real teenagers."[35]

Publication and reception

editCritical reception

editOn Metacritic, the book received a 77 out of 100 based on 23 critic reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[40] Liesl Schillinger of The New York Times praised the novel's various themes and suspenseful ending. However, she considered Rowling's gift "not so much for language as for characterisation and plotting."[36] Kirkus Reviews said it "will leave readers pleased, amused, excited, scared, infuriated, delighted, sad, surprised, thoughtful and likely wondering where Voldemort has got to, since he appears only in flashbacks." They considered Rowling's "wry wit" to turn into "outright merriment" but called the climax "tragic, but not uncomfortably shocking."[41] Yvonne Zipp of The Christian Science Monitor praised the way Rowling evolved Harry into a teenager and how the plot threads found as far back as Chamber of Secrets came into play. On the other hand, she noted it "gets a little exposition-heavy in spots," and older readers may have seen the ending coming.[33]

The Boston Globe correspondent Liz Rosenberg wrote, "The book bears the mark of genius on every page" and praised the imagery and darker tone of the book, considering that the series could be crossing over from fantasy to horror.[34] The Associated Press writer Deepti Hajela praised the newfound emotional tones and ageing Harry to the point at which "younger fans may find [the series] has grown up too much."[39] Emily Green, a staff writer for the Los Angeles Times, was generally positive about the book but was concerned whether young children could handle the material.[42] Cultural critic Julia Keller of the Chicago Tribune called it the "most eloquent and substantial addition to the series thus far" and considered the key to the success of the Potter novels to be humour.[38]

Awards and honours

editHarry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince won several awards, including the 2006 British Book of the Year Award[43] and the 2006 Royal Mail Award for Scottish Children's Books for ages 8–12 in its native United Kingdom.[44] In the United States, the American Library Association listed it among its 2006 Best Books for Young Adults.[45] It won both the 2005 reader-voted Quill Awards for Best Book of the Year and Best Children's Book.[46][47] It also won the Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Platinum Seal for notable book.[48]

Sales

editBefore publication, 1.4 million pre-orders were placed for Half-Blood Prince on Amazon.com, breaking the record held by the previous novel, Order of the Phoenix, with 1.3 million.[49] The initial print run for Half-Blood Prince was a record-breaking 10.8 million.[50] Within the first 24 hours after release, the book sold 9 million copies worldwide: 2 million in the UK and about 6.9 million in the US,[51] which prompted Scholastic to rush an additional 2.7 million copies into print.[52] Within the first nine weeks of publication, 11 million copies of the US edition were reported to have been sold.[53] The US audiobook, read by Jim Dale, set sales records with 165,000 sold over two days, besting the adaptation of Order of the Phoenix by twenty percent.[54]

Translations

editHarry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was published simultaneously in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.[55] Along with the rest of the books in the Harry Potter series, it was eventually translated into 67 languages.[56] However, because of high security surrounding the manuscript, translators did not get to start on translating Half-Blood Prince until its English release date, and the earliest were not expected to be released until the fall of 2005.[57] In Germany, a group of "hobby translators" translated the book via the internet less than two days after release, long before German translator Klaus Fritz could translate and publish the book.[58]

Editions

editSince its wide hardcover release on 16 July 2005, Half-Blood Prince was released as a paperback on 23 June 2006 in the UK.[59] Two days later on 25 July, the paperback edition was released in Canada[60] and the US, where it had an initial print run of 2 million copies.[61] To celebrate the release of the American paperback edition, Scholastic held a six-week sweepstakes event in which participants in an online poll were entered to win prizes.[62] Simultaneous to the original hardcover release was the UK adult edition that featured a new cover[63] and was also released as a paperback on 23 June.[64] Also released on 16 July was the Scholastic "Deluxe Edition," which featured reproductions of Mary GrandPré's artwork and had a print run of about 100,000 copies.[65] Bloomsbury later released a paperback "Special Edition" on 6 July 2009[66] and a "Signature Edition" paperback on 1 November 2010.[67]

Adaptations

editFilm

editThe film adaptation of the sixth book was originally scheduled to be released on 21 November 2008 but was changed to 15 July 2009.[68][69] Directed by David Yates, the screenplay was adapted by Steve Kloves and produced by David Heyman and David Barron.[70] The film grossed over $934 million worldwide,[71] which made it the second-highest-grossing film of 2009 worldwide[72] and the fifteenth-highest of all time.[73] Additionally, Half-Blood Prince gained an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography.[74][75]

Video games

editA video game adaptation of the book was developed by EA Bright Light Studio and published by Electronic Arts in 2009. The game was available on the Microsoft Windows, Nintendo DS, PlayStation 2, PlayStation 3, PlayStation Portable, Wii, Xbox 360, and macOS platforms.

The book was also adapted in the 2011 video game Lego Harry Potter: Years 5–7.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "11 Million Copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Sold in First Nine Weeks | Scholastic Media Room". mediaroom.scholastic.com. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "'Deathly Hallows' sold 15 mn copies in 24 hours". Inshorts - Stay Informed. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "Book 6 – The Half-Blood Prince". CBBC Newsround. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Speed-reading after lights out". The Guardian. UK. 19 July 2000. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "A Potter timeline for muggles". Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Cassy, John (16 January 2003). "Harry Potter and the hottest day of summer". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "July date for Harry Potter book". BBC News. 21 December 2004. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Elisco, Lester (2000–2009). "The Phenomenon of Harry Potter". TomFolio.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- ^ Knapp, N.F. (2003). "In Defense of Harry Potter: An Apologia" (PDF). School Libraries Worldwide. 9 (1). International Association of School Librarianship: 78–91. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ^ "A Potter timeline for muggles". Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter: Meet J.K. Rowling". Scholastic Inc. Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Speed-reading after lights out". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. 19 July 2000. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Everything you might want to know". J.K. Rowling Official Site. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Rowling unveils last Potter date". BBC. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m". BBC. 23 July 2007. Archived from the original on 28 November 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ^ "World Book Day Webchat, March 2004". Bloomsbury. March 2004. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. (15 March 2004). "Progress on Book Six". J.K. Rowling Official Site. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. "The Opening Chapter of Book Six". J.K. Rowling Official Site. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Read the FULL J.K. Rowling interview". CBBC Newsround. 18 July 2005. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. "Do you like 'Half-Blood Prince'?". J.K. Rowling Official Site. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Editorial, Reuters (11 November 2010). "Factbox: Main events in creation of Harry Potter phenomenon". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Rowling, J.K. (29 June 2004). "Title of Book Six: The Truth". J.K. Rowling Official Site. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "JK Rowling finishes sixth Potter book". The Guardian. UK. 21 December 2004. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (23 December 2004). "WEEK IN REVIEW: Martha Seeks Prison Reform". People. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Latest Potter book cover revealed". CBBC Newsround. 8 March 2005. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Bets reopen on Dumbledore death". BBC. 25 May 2005. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Pauli, Michelle (3 March 2005). "Praise for 'forest friendly' Potter". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 18 September 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Malvern, Jack; Cleroux, Richard (13 July 2005). "Reading ban on leaked Harry Potter". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Geist, Michael (12 July 2005). "The Harry Potter Injunction". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Stallman, Richard. "Don't Buy Harry Potter Books". Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ "Much Ado As Harry Potter Hits the Shelves". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 16 July 2005. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ "Important Notice: Raincoast Books". Raincoast.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ a b c Zipp, Yvonne (18 July 2005). "Classic Book Review: Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, Liz (18 July 2005). "'Prince' shines amid growing darkness". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b Paolini, Christopher (20 July 2005). "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ a b Schillinger, Liesl (31 July 2005). "'Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince': Her Dark Materials". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Kipen, David (17 July 2005). "Book Review: Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ a b Keller, Julia (17 July 2005). "Tragic? Yes, but humor triumphs". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ a b Hajela, Deepti (18 July 2005). "Emotional twists come with a grown-up Harry". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter And The Half-Blood Prince [Book 6]". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "'Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince': The Kirkus Review". Kirkus Reviews. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Green, Emily (16 July 2005). "Harry's back, and children must be brave". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ "Previous Winners". Literaryawards.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Previous Winners and Shortlisted Books". Scottish Book Trust. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Best Books for Young Adults". 2006. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Carol (14 October 2005). "Books Get Glamorous—And Serious". Bookreporter.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "2005 Quill Awards". Bookreporter.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince". Arthur A. Levine Books. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Alfano, Sean (13 July 2005). "Potter Sales Smash Own Record". CBS News. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "2000–2009 – The Decade of Harry Potter Gives Kids and Adults a Reason to Love Reading" (Press release). Scholastic. 15 December 2009. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "New Potter book topples U.S. sales records". NBC News. Associated Press. 18 July 2005. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Memmott, Carol (17 July 2005). "Potter-mania sweeps USA's booksellers". USA Today. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ "11 million Copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Sold in the First Nine Weeks" (Press release). New York: Scholastic. 21 September 2005. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ "Audio Book Sales Records Set By J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince" (PDF) (Press release). Random House. 18 July 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Potter book six web scam foiled". CBBC Newsround. 11 January 2005. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Flood, Alison (17 June 2008). "Potter tops 400 million sales". TheBookseller.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter en Español? Not quite yet". MSNBC News. 26 July 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Diver, Krysia (1 August 2005). "Germans in a hurry for Harry". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Rowling, J. K. (2006). Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (Paperback). Bloomsbury. ISBN 0747584680.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Available in Paperback". Raincoast Books. 24 July 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ "J.K. Rowling's Phenomenal Bestseller Harry Potter and The Half-Blood Prince to Be Released in Paperback on July 25, 2006" (Press release). New York: Scholastic. 18 January 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ "Scholastic Kicks-Off Harry Potter 'Wednesdays' Sweepstakes to Win Harry Potter iPods(R) and Copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince With Bookplates Signed by J.K. Rowling" (Press release). New York: Scholastic. 23 February 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Rowling, J. K. (2005). Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Adult Edition. Bloomsbury. ISBN 074758110X.

- ^ Rowling, J. K. (2006). Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Adult Edition (Paperback). Bloomsbury. ISBN 0747584664.

- ^ "Scholastic Releases Exclusive Artwork for Deluxe Edition of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince" (Press release). New York: Scholastic. 11 May 2005. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Rowling, J. K. (2009). Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Special Edition (Paperback). Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0747598466. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Allen, Katie (30 March 2010). "Bloomsbury Repackages Harry Potter". TheBookseller.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Eng, Joyce (15 April 2005). "Coming Sooner: Harry Potter Changes Release Date". TVGuide. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ Child, Ben (15 August 2008). "Harry Potter film delayed eight months". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince full production credits". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "2009 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "All-Time Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 82nd Academy Awards". AMPAS. AMPAS. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Strowbridge, C.S. (19 September 2009). "International Details — Dusk for Ice Age". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.