Health human resources (HHR) – also known as human resources for health (HRH) or health workforce – is defined as "all people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance positive health outcomes", according to World Health Organization's World Health Report 2006.[2] Human resources for health are identified as one of the six core building blocks of a health system.[3] They include physicians, nursing professionals, pharmacists, midwives, dentists, allied health professions, community health workers, and other social service and health care providers.

Health human resources are further composed of health management and support personnel: those who do not provide direct patient care but add important value to enhance health system efficiency, effectiveness and equity. They include health services managers, medical records and health information technicians, health economists, health supply chain managers, medical secretaries, facility maintenance workers, and others.

The field of HHR deals with issues such as workforce planning and policy evaluation, recruitment and retention, training and development of skilled personnel, performance management, health workforce information systems, and research on health workforce strengthening. Raising awareness of the critical role of human resources in the health care sector - particularly as exacerbated by health labour shortages stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic - has placed the health workforce as one of the highest priorities of the global health agenda.[4][5]

Global situation

editThe World Health Organization (WHO) raised the profile of HHR as a global health concern with its landmark 2006 published estimate of a shortage of almost 4.3 million physicians, midwives, nurses and support workers to meet the Millennium Development Goals, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.[2] The situation was declared on World Health Day 2006 as a "health workforce crisis" – the result of decades of underinvestment in health worker education, training, wages, working environment and management. The WHO currently projects a global shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030, mostly in low- and lower-middle income countries.[6]

Shortages of skilled for health workers are also reported in many specific care areas. For example, there is an estimated shortage of 1.18 million mental health professionals, including 55,000 psychiatrists, 628,000 nurses in mental health settings, and 493,000 psychosocial care providers needed to treat mental disorders in 144 low- and middle-income countries.[7] Shortages of skilled birth attendants in many developing countries remains an important barrier to improving maternal health outcomes. Physiotherapists and rehabilitation medical specialists have been found to be less available in low- and middle-income countries, despite greater need.[8]

Many countries, both developed and developing, report geographical maldistribution of skilled health workers leading to shortages in rural and underserved areas.[9]

The advancement of global health security and universal health coverage (UHC) is hampered by a number of serious issues facing the global health workforce. The anticipated scarcity of health workers is a significant problem. The World Health Organisation (WHO) projects that by 2030,[10] there will be a shortage of 18 million health workers worldwide, with low- and lower-middle-income nations bearing a disproportionate share of this burden. The provision of necessary health services is directly impacted by this scarcity, which also hinders the goal of establishing UHC. Access to healthcare is severely limited in many locations due to a shortage of skilled health personnel, particularly for disadvantaged populations.

The unequal distribution of health professionals, which clearly shows an urban-rural gap, is another issue. Health professionals are frequently more concentrated in urban areas, underserving isolated and rural locations.[11] Rural communities suffer from worse health outcomes and unequal access to healthcare as a result of this discrepancy. Closing these disparities requires initiatives aimed at drawing and keeping health professionals in rural regions.

Imbalances in skills make matters more difficult. The requirements of the populace and the health workforce are sometimes at odds in many areas. For instance, there can be an excess of specialists and a deficiency of primary care physicians.[12] This mismatch results in gaps in service delivery and ineffective use of human resources.

These difficulties have been made worse by the COVID-19 outbreak. Burnout, mental health problems, and higher attrition rates have been experienced by health professionals.[13] According to a WHO poll conducted in 2022, stress associated to pandemics caused up to 40% of health personnel to consider quitting their employment.[14] Maintaining healthcare systems requires addressing mental health assistance for healthcare professionals.[15]

The health workforce is profoundly shaped by gender dynamics. Women make up over 70% of the workforce in the health sector worldwide, yet as of 2023, only 25% of leaders in health organisations were female.[16] Healthcare policy formulation and decision-making are impacted by this gender disparity.

There is still a gender pay difference, even in wealthy nations. According to a 2022 study, female doctors make, on average, 24% less than their male colleagues.[17]

There is also clear occupational segregation, with women occupying 90% of nursing positions worldwide while men still predominate in surgery (19% of women).[18] Career options are restricted by this segmentation, which has its roots in societal conventions. Finally, intersectionality matters because women from minority backgrounds have more obstacles to career progression because of prejudice based on both race and gender.

Conclusion:

The COVID-19 pandemic's persistent effects, shortages, uneven distribution, and skill imbalances are placing a tremendous burden on the world's health workforce. Gender inequality not only presents structural obstacles but also persistently influences the lives and prospects of health workers across the globe. Coordinated international efforts are needed to solve these problems, with an emphasis on advancing gender equality, resolving skill gaps, and making sure that health professionals everywhere have the resources they need to deliver high-quality treatment. The international health community can endeavour to develop a more resilient and equitable health workforce by tackling these issues.

Regular statistical updates on the global health workforce situation are collated by the WHO's Global Health Observatory.[19] However, the evidence base remains fragmented and incomplete, largely related to weaknesses in the underlying human resource information systems (HRIS) within countries.[20]

In order to learn from best practices in addressing health workforce challenges and strengthening the evidence base, an increasing number of HHR practitioners from around the world are focusing on issues such as HHR advocacy, equity, surveillance and collaborative practice. Some examples of global HRH partnerships include:

Research

editHealth workforce research is the investigation of how social, economic, organizational, political and policy factors affect access to health care professionals, and how the organization and composition of the workforce itself can affect health care delivery, quality, equity, and costs.

Many government health departments, academic institutions and related agencies have established research programs to identify and quantify the scope and nature of HHR problems leading to health policy in building an innovative and sustainable health services workforce in their jurisdiction. Some examples of HRH information and research dissemination programs include:

- Human Resources for Health journal

- HRH Knowledge Hub, University of New South Wales, Australia

- Center for Health Workforce Studies, University of Albany, New York

- Canadian Institute for Health Information: Spending and Health Workforce

- Public Health Foundation of India: Human Resources for Health in India

- National Human Resources for Health Observatory of Sudan Archived 2022-09-09 at the Wayback Machine

- OECD Human Resources for Health Care Study

Training and Development

editTraining and development are vital, especially in the healthcare sector, as they ensure that the health force remains informed and educated about new advancements and innovations, which enhance patient safety and care.[21] Similarly, by demonstrating to staff members that their professional development is valued, continuous professional development (CPD) increases job satisfaction and retention and lowers turnover rates.[22] In addition, proficient personnel exhibit greater efficiency and adaptability, augmenting operational efficiency and facilitating healthcare establishments in fulfilling regulatory requirements.[23] Furthermore, a dedication to continuous learning cultivates a climate of creativity and cooperation, which improves healthcare results.[24]

Technological innovations have played a crucial role in the healthcare sector's ongoing growth.[25] Consequently, healthcare companies must maintain their dedication to improving the competencies and expertise of their personnel, particularly in domains that offer a competitive edge.[26] Knowledge management, training, and development are the three main components of organizational growth and development.[27] Training and development, in Maimuna's opinion, are tools that help human capital explore their dexterity; as a result, they are essential to an organization's workforce's productivity.[28] Digital education, if properly designed and implemented, can strengthen health workforce capacity by delivering education to remote areas and enabling continuous learning for health workers. World Health Organization (WHO) is developing guidelines on digital education for health workforce education and training. The WHO addresses the global health workforce crisis by providing comprehensive guidelines to improve health professional education and training that advocate for substantial educational reforms, including updating curricula, improving tutoring facilities, and revising admission criteria. It emphasizes the importance of increasing both the quantity and quality of healthcare professionals, making certain that they are adequately prepared to address evolving health needs, and highlights the necessity for interaction among the workforce, finance, health, and academic sectors to effectively implement these changes and achieve the overarching goal of developing a more efficient and suitable health workforce.[29]

Types

editSeveral Training Programs available in the health sector include:

1. Training in Leadership and Management Programs.[30]

2. Training in Emergency Preparedness.[31]

3. Continuing Professional Education.[32][needs update]

4. Technical skill training.[33]

5. Instruction in Patient Safety.[34]

6. Cultural Competency Training.[35]

Leadership Development

editLeadership management and training is to ensure that the health force is established with skills and power to tackle the challenges and barriers experienced in the health sector. Training programs can often provide evidence-based teaching practices with experiential learning and are essential to developing successful and powerful leaders who can oversee the complexity of the healthcare system and can optimize patient outcomes. For instance, according to BMJ Leader, effective medical leadership programs frequently combine various teaching strategies, such as seminars, group projects, and action learning, which enhances results on several fronts.[36] According to Medical Science Educators, transformational leadership is centered on developing trusting connections between leaders and subordinates, which improves job fulfillment, motivation, and staff loss, all leading to better healthcare delivery.[37] Another study by Public Personnel Management examines how high-performance work systems and the job demands-resource theory relate to the impact of training and development access on employee engagement at work.[38] The study demonstrates that greater rates of work engagement among federal employees are positively correlated with access to chances for training and development. It emphasizes how important it is for leaders to participate in leadership development programs because they give them the tools to create a positive work atmosphere that improves employee engagement and organizational performance.[38]

Challenges and Solutions

editHealthcare training and development encounter particular problems such as worker stress, scheduling conflicts, fast technology change, disease control protocols, and limited resources. Solutions for this include putting in place wellness initiatives, providing flexible and online training, ongoing education, and utilizing virtual reality (VR) technology[39] to create comfortable training settings. Financial difficulties can also be lessened by obtaining grants and collaborations, and healthcare personnel can stay knowledgeable and proficient through simulation-based training, interprofessional collaboration, and ongoing professional development. Frequent evaluation and feedback increase the efficacy of training, which eventually improves staff satisfaction and patient care.

Future Trends

editThe adoption of technology, personal learning, and continuous professional development (CPD) are expected to be key components of future developments in healthcare training and development. Virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI) are being used more frequently to provide stimulating and interactive training encounters.[39] Considerable importance is placed on continuing education and professional development (CPD) to guarantee that healthcare personnel stay ahead with the most recent developments in medicine.[22] The goal of these trends is to improve the treatment of patients and their results by strengthening the abilities and capabilities of healthcare professionals.

Policy and planning

editIn some countries and jurisdictions, health workforce planning is distributed among labour market participants. In others, there is an explicit policy or strategy adopted by governments and systems to plan for adequate numbers, distribution and quality of health workers to meet health care goals. For one, the International Council of Nurses reports:[40]

The objective of HHRP [health human resources planning] is to provide the right number of health care workers with the right knowledge, skills, attitudes, and qualifications, performing the right tasks in the right place at the right time to achieve the right predetermined health targets.

An essential component of planned HRH targets is supply and demand modeling, or the use of appropriate data to link population health needs and/or health care delivery targets with human resources supply, distribution and productivity. The results are intended to be used to generate evidence-based policies to guide workforce sustainability.[41][42] In resource-limited countries, HRH planning approaches are often driven by the needs of targeted programmes or projects, for example, those responding to the Millennium Development Goals or, more recently, the Sustainable Development Goals.[43]

The WHO Workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN) is an HRH planning and management tool that can be adapted to local circumstances.[44] It provides health managers a systematic way to make staffing decisions in order to better manage their human resources, based on a health worker's workload, with activity (time) standards applied for each workload component at a given health facility. Health workforce planning is essential for ensuring that health systems possess the appropriate number of skilled workers in suitable locations at optimal times to address care demands.The International Council of Nurses states that Health Human Resources Planning (HHRP) aims to synchronize the number of healthcare professionals with the requisite skills, attitudes, and qualifications to achieve established health objectives. Effective Health Human Resource Planning (HHRP) is heavily reliant on supply and demand modelling, utilizing data to connect population health requirements with the availability and productivity of human resources, hence facilitating workforce sustainability. Planning frequently emphasizes programmatic requirements, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in resource-constrained environments. The WHO workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN) tool aids in human resources for health planning by assisting health managers in making staffing decisions grounded in health workers' workloads and time standards at healthcare facilities.

Human Resource Planning (HRP) is essential to organizational success. It guarantees that appropriate people occupy suitable positions, promoting the effective execution of managerial tasks such as planning, organizing, and directing. In addition to employment, human resource planning encompasses tactics to enhance employee productivity and retention, including training, performance evaluations, and incentives. These employee engagement and reward methods are not just strategies, but a way to show appreciation and motivate the workforce. Effective human resource planning inspires people, increases productivity, and assures the seamless operation of organizations. Integrating data-driven workforce planning with these employee engagement and reward methods enables health systems and organizations to attain sustainable, long- term success.[1]

Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel

editThe main international policy framework for addressing shortages and maldistribution of health professionals is the Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, adopted by the WHO's 63rd World Health Assembly in 2010.[45] The Code was developed in a context of increasing debate on international health worker recruitment, especially in some higher income countries, and its impact on the ability of many third-world countries to deliver primary health care services. Although non-binding on the Member States and recruitment agencies, the Code promotes principles and practices for the ethical international recruitment of health personnel. It also advocates the strengthening of health personnel information systems to support effective health workforce policies and planning in countries

Gender and health workforce

editThe WHO estimates women comprise approximately 70% of the global health workforce, but gender equality remains elusive.[46][47] Women’s contributions to health and social care services are markedly undervalued; health labour markets around the world continue to be characterized with gender-based occupational segregation, inadequate work conditions free from gender bias and sexual harassment, gender pay gaps, and lack of gender parity in leadership.[46] Numerous HHR studies have shown women healthcare providers earn significantly less on average than men despite similar professional titles, qualifications and job responsibilities.[46][9] Meanwhile, an estimated 75% of HHR leadership roles are held by men.[47]

See also

editReferences

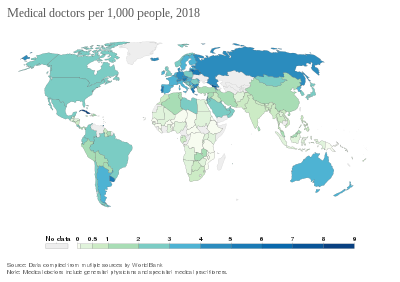

edit- ^ "Medical doctors per 1,000 people". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ a b "The world health report 2006: working together for health". World Health Organization. Geneva. 2006. Archived from the original on December 2, 2006.

- ^ "Health Systems Topics". World Health Organization. Geneva. Archived from the original on January 29, 2007.

- ^ Grépin, Karen A; Savedoff, William D (November 2009). "10 Best Resources on ... health workers in developing countries". Health Policy and Planning. 24 (6): 479–482. doi:10.1093/heapol/czp038. PMID 19726562.

- ^ Gupta, Neeru; Balcom, Sarah; Gulliver, Adrienne; Witherspoon, Richelle (March 2021). "Health workforce surge capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic and other global respiratory disease outbreaks: A systematic review of health system requirements and responses". International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 24 (36): 26–41. doi:10.1002/hpm.3137. PMC 8013474.

- ^ "Health Workforce". World Health Organization. Geneva. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Scheffler, RM; et al. (2011). "Human resources for mental health: workforce shortages in low- and middle-income countries" (PDF). World Health Organization. Geneva.

- ^ Gupta, Neeru; Castillo-Laborde, Carla; Landry, Michel D (Oct 2011). "Health-related rehabilitation services: assessing the global supply of and need for human resources". Human Resources for Health. 11 (276): 276. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-276. PMC 3207892. PMID 22004560.

- ^ a b Gupta, Neeru; Gulliver, Adrienne; Singh, Paramdeep (June 2023). "Relative remoteness and wage differentials in the Canadian allied health professional workforce". Rural and Remote Health. 23 (2): 7882. doi:10.22605/RRH7882. PMID 37264595.

- ^ Scheffler, Richard M.; Tulenko, Kate; et al. (2016-08-20). "The deepening global health workforce crisis: Forecasting needs, shortages, and costs for the global strategy on human resources for health (2013-2030)". Annals of Global Health. 82 (3): 510. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2016.04.386. ISSN 2214-9996.

- ^ Dussault, Gilles; Franceschini, Maria Cristina (2006-05-27). "Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce". Human Resources for Health. 4 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-4-12. ISSN 1478-4491. PMC 1481612. PMID 16729892.

- ^ Campbell, James; Buchan, James; Cometto, Giorgio; David, Benedict; Dussault, Gilles; Fogstad, Helga; Fronteira, Inês; Lozano, Rafael; Nyonator, Frank; Pablos-Méndez, Ariel; Quain, Estelle E; Starrs, Ann; Tangcharoensathien, Viroj (2013-11-01). "Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 91 (11): 853–863. doi:10.2471/blt.13.118729. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 3853950. PMID 24347710.

- ^ Dehkordi, Amirhoshang Hoseinpour; Nemati, Reza; Tavousi, Pouya (2020). "A deeper look at COVID-19 CFR: health care impact and roots of discrepancy". doi:10.1101/2020.04.22.20071498. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dehkordi, Amirhoshang Hoseinpour; Nemati, Reza; Tavousi, Pouya (2020). "A deeper look at COVID-19 CFR: health care impact and roots of discrepancy". doi:10.1101/2020.04.22.20071498. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dehkordi, Amirhoshang Hoseinpour; Nemati, Reza; Tavousi, Pouya (2020). "A deeper look at COVID-19 CFR: health care impact and roots of discrepancy". doi:10.1101/2020.04.22.20071498. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Boniol, M.; McIsaac, M.; Xu, L.; Wuliji, T.; Diallo, K.; et al. (2019). Gender equity in the health workforce: analysis of 104 countries (Report). World Health Organization.

- ^ Newman, Constance (2014-05-06). "Time to address gender discrimination and inequality in the health workforce". Human Resources for Health. 12 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-12-25. ISSN 1478-4491. PMC 4014750. PMID 24885565.

- ^ Witter, Sophie; Namakula, Justine; Wurie, Haja; Chirwa, Yotamu; So, Sovanarith; Vong, Sreytouch; Ros, Bandeth; Buzuzi, Stephen; Theobald, Sally (2017-12-01). "The gendered health workforce: mixed methods analysis from four fragile and post-conflict contexts". Health Policy and Planning. 32 (suppl_5): v52–v62. doi:10.1093/heapol/czx102. ISSN 0268-1080. PMC 5886261. PMID 29244105.

- ^ "Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: Health workforce". World Health Organization. Geneva. Archived from the original on June 20, 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Dal Poz, MR; et al., eds. (2009). "Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health". World Health Organization. Geneva. Archived from the original on October 14, 2009.

- ^ Markaki, Adelais; Malhotra, Shreya; Billings, Rebecca; Theus, Lisa (2021-05-31). "Training needs assessment: tool utilization and global impact". BMC Medical Education. 21 (1): 310. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02748-y. ISSN 1472-6920. PMC 8167940. PMID 34059018.

- ^ a b Mlambo, Mandlenkosi; Silén, Charlotte; McGrath, Cormac (2021-04-14). "Lifelong learning and nurses' continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature". BMC Nursing. 20 (1): 62. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00579-2. ISSN 1472-6955. PMC 8045269. PMID 33853599.

- ^ Ayeleke, Reuben Olugbenga; North, Nicola Henri; Dunham, Annette; Wallis, Katharine Ann (2019-01-01). "Impact of training and professional development on health management and leadership competence: A mixed methods systematic review". Journal of Health Organization and Management. 33 (4): 354–379. doi:10.1108/JHOM-11-2018-0338. ISSN 1477-7266. PMID 31282815.

- ^ Willie, Michael Mncedisi (2023). "Strategies for Enhancing Training and Development in Healthcare Management". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4567415. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ Thimbleby, Harold (2012–2013). "Technology and the Future of Healthcare". Journal of Public Health Research. 2 (3): jphr.2013.e28. doi:10.4081/jphr.2013.e28. ISSN 2279-9036. PMC 4147743. PMID 25170499.

- ^ Bohr, Adam; Memarzadeh, Kaveh (2020), "The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications", Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, Elsevier: 25–60, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818438-7.00002-2, ISBN 978-0-12-818438-7, PMC 7325854

- ^ Dinah Gould, Daniel Kelly (2004). "Training needs analysis: an evaluation framework". Nursing Standard. 18 (20): 33–36. doi:10.7748/ns2004.01.18.20.33.c3534. PMID 14976702. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

- ^ 1.Maimuna 2.Yazdanifard Nda, 1. Muhammad 2. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rashad (December 12, 2013). "THE IMPACT OF EMPLOYEE TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT ON EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY". Global Journal of Commerce & Management. 2 (6). Global Institute for Research & Education: 91–93.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization (2013). Transforming and scaling up health professionals' education and training: World Health Organization guidelines 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-150650-2.

- ^ Giovanelli, Lucia; Rotondo, Federico; Fadda, Nicoletta (2024-08-07). "Management training programs in healthcare: effectiveness factors, challenges and outcomes". BMC Health Services Research. 24 (1): 904. doi:10.1186/s12913-024-11229-z. ISSN 1472-6963. PMC 11308623. PMID 39113015.

- ^ Bedi, Jasbir Singh; Vijay, Deepthi; Dhaka, Pankaj; Singh Gill, Jatinder Paul; Barbuddhe, Sukhadeo B. (March 2021). "Emergency preparedness for public health threats, surveillance, modelling & forecasting". Indian Journal of Medical Research. 153 (3): 287–298. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_653_21. ISSN 0971-5916. PMC 8204835. PMID 33906991.

- ^ Opiyo, Newton; English, Mike (2010-04-14), The Cochrane Collaboration (ed.), "In-service training for health professionals to improve care of the seriously ill newborn or child in low and middle-income countries (Review)", Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4), Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: CD007071, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007071.pub2, PMC 2868967, PMID 20393956

- ^ Leonardsen, Ann-Chatrin Linqvist; Blågestad, Ina Kristin; Brynhildsen, Siri; Olsen, Richard; Gunheim-Hatland, Lars; Gregersen, Anne-Grethe; Kvarsnes, Anne Herwander; Hansen, Wenche Charlotte; Andreassen, Hilde Marie; Martinsen, Mona; Hansen, Mette; Hjelmeland, Inger; Grøndahl, Vigdis Abrahamsen (September 2020). "Nurses' perspectives on technical skill requirements in primary and tertiary healthcare services". Nursing Open. 7 (5): 1424–1430. doi:10.1002/nop2.513. ISSN 2054-1058. PMC 7424445. PMID 32802362.

- ^ Mistri, Isha U.; Badge, Ankit; Shahu, Shivani; Mistri, Isha U.; Badge, Ankit; Shahu, Shivani (2023-12-27). "Enhancing Patient Safety Culture in Hospitals". Cureus. 15 (12): e51159. doi:10.7759/cureus.51159. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 10811440. PMID 38283419.

- ^ Stubbe, Dorothy E. (January 2020). "Practicing Cultural Competence and Cultural Humility in the Care of Diverse Patients". Focus. 18 (1): 49–51. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20190041. ISSN 1541-4094. PMC 7011228. PMID 32047398.

- ^ Lyons, Oscar; George, Robynne; Galante, Joao R.; Mafi, Alexander; Fordwoh, Thomas; Frich, Jan; Geerts, Jaason Matthew (2021-09-01). "Evidence-based medical leadership development: a systematic review". BMJ Leader. 5 (3): 206–213. doi:10.1136/leader-2020-000360. hdl:10852/93213. ISSN 2398-631X. PMID 37850339.

- ^ Gabel, Stewart (2013-03-01). "Transformational Leadership and Healthcare". Medical Science Educator. 23 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1007/BF03341803. ISSN 2156-8650.

- ^ a b Hassett, Michael P. (September 2022). "The Effect of Access to Training and Development Opportunities, on Rates of Work Engagement, Within the U.S. Federal Workforce". Public Personnel Management. 51 (3): 380–404. doi:10.1177/00910260221098189. ISSN 0091-0260.

- ^ a b Pottle, Jack (2019-10-01). "Virtual reality and the transformation of medical education". Future Healthcare Journal. 6 (3): 181–185. doi:10.7861/fhj.2019-0036. ISSN 2514-6645. PMC 6798020. PMID 31660522.

- ^ "Health human resources planning" (PDF). International Council of Nurses. Geneva. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Dal Poz, MR; et al. (2010). "Models and tools for health workforce planning and projections" (PDF). World Health Organization. Geneva.

- ^ "Health Human Resource Strategy (HHRS)". Health Canada. 21 September 2004. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ Dreesch, N; et al. (September 2005). "An approach to estimating human resource requirements to achieve the Millennium Development Goals". Health Policy and Planning. 20 (5): 267–276. doi:10.1093/heapol/czi036. PMID 16076934.

- ^ "Workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN): User's manual". World Health Organization. Geneva. 2010. Archived from the original on March 30, 2011.

- ^ International recruitment of health personnel: global code of practice, Geneva: The Sixty-third World Health Assembly, May 2010

- ^ a b c Delivered by women, led by men: a gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019, hdl:10665/311322, ISBN 9789241515467

- ^ a b Value gender and equity in the global health workforce, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2023

External links

edit- World Health Organization programme of work on health human resources

- Human Resources for Health Databases, Canadian Institute for Health Information

- Human resources for health in developing countries – a dossier from the Institute for Development Studies

- Compendium of tools and guidelines for HRH situation analysis, planning, policies and management systems

- Online community of practice for HRH practitioners on strengthening health workforce information systems

- Human Resources for Health Global Resource Center online collection of HRH research and materials, supported by the IntraHealth International-led CapacityPlus project

- HRIS strengthening implementation toolkit Archived 2011-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Africa Health Workforce Observatory