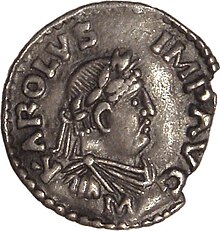

The phantom time conspiracy theory is a pseudohistorical conspiracy theory first asserted by Heribert Illig in 1991. It hypothesizes a conspiracy by the Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, Pope Sylvester II, and possibly the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII,[further explanation needed] to fabricate the Anno Domini dating system retroactively, in order to place them at the special year of AD 1000, and to rewrite history[1] to legitimize Otto's claim to the Holy Roman Empire. Illig believed that this was achieved through the alteration, misrepresentation and forgery of documentary and physical evidence.[2] According to this scenario, the entire Carolingian period, including the figure of Charlemagne, is a fabrication, with a "phantom time" of 297 years (AD 614–911) added to the Early Middle Ages.

Evidence contradicts the hypothesis and it failed to gain the support of historians, and calendars in other European countries, most of Asia and parts of pre-Columbian America contradict this.[3][4][5][6]

Heribert Illig

editIllig was born in 1947 in Vohenstrauß, Bavaria. He was active in an association dedicated to Immanuel Velikovsky, catastrophism and historical revisionism, the Gesellschaft zur Rekonstruktion der Menschheits- und Naturgeschichte (English: Society for the Reconstruction of Human and Natural History). From 1989 to 1994 he acted as editor of the journal Vorzeit-Frühzeit-Gegenwart (English: Prehistory-Proto-History-Present). Since 1995, he has worked as a publisher and author under his own publishing company, Mantis-Verlag, and publishing his own journal, Zeitensprünge (English: Leaps in Time). Outside of his publications related to revised chronology, he has edited the works of Egon Friedell.

Before focusing on the early medieval period, Illig published various proposals for revised chronologies of prehistory and of Ancient Egypt. His proposals received prominent coverage in German popular media in the 1990s. His 1996 Das erfundene Mittelalter (English: The Invented Middle Ages) also received scholarly recensions, but was universally rejected as fundamentally flawed by historians.[7] In 1997, the journal Ethik und Sozialwissenschaften (English: Ethics and Social Sciences) offered a platform for critical discussion to Illig's proposal, with a number of historians commenting on its various aspects.[8] After 1997, there has been little scholarly reception of Illig's ideas, although they continued to be discussed as pseudohistory in German popular media.[9] Illig continued to publish on the "phantom time hypothesis" until at least 2013. Also in 2013, he published on an unrelated topic of art history, on German Renaissance master Anton Pilgram, but again proposing revisions to conventional chronology, and arguing for the abolition of the art historical category of Mannerism.[10]

Claims

editIllig's claims include:[11][12]

- That there is a scarcity of archaeological evidence that can be reliably dated to the period AD 614–911.

- That the dating methods used for such recent periods, radiometry and dendrochronology, are inaccurate.

- That medieval historians rely too much on written sources.

- That the presence of Romanesque architecture in tenth-century Western Europe suggests that the Roman era was not as long ago as conventionally thought.

- That at the time of the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in AD 1582, there should have been a discrepancy of thirteen days between the Julian calendar and the real (or tropical) calendar, when the astronomers and mathematicians working for Pope Gregory XIII had found that the civil calendar needed to be adjusted by only ten days. From this, Illig concludes that the AD era had counted roughly three centuries which never existed.

Refutation

edit- Observations in ancient astronomy, especially those of solar eclipses cited by European sources prior to 600 AD (when phantom time would have distorted the chronology), agree with the usual chronology and not with Illig's. Besides several others that are perhaps too vague to disprove the phantom time hypothesis, two in particular are dated with enough precision to question the hypothesis. One is reported by Pliny the Elder in 59 AD.[13] This date has a confirmed eclipse. In addition, observations during the Tang dynasty in China, and Halley's Comet, for example, are consistent with current astronomy with no "phantom time" added.[14][3]

- Archaeological remains and dating methods such as dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) refute, rather than support, "phantom time".[4]

- The Gregorian reform was never purported to bring the calendar in line with the Julian calendar as it had existed at the time of its institution in 45 BC, but as it had existed in 325 AD, the time of the Council of Nicaea, which had established a method for determining the date of Easter Sunday by fixing the vernal equinox on March 21 in the Julian calendar. By 1582, the astronomical equinox was occurring on March 10 in the Julian calendar, but Easter was still being calculated from a nominal equinox on March 21. In 45 BC the astronomical vernal equinox took place around March 23. Illig's "three missing centuries" thus correspond to the 369 years between the institution of the Julian calendar in 45 BC, and the fixing of the Easter Date at the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.[5]

- If Charlemagne and the Carolingian dynasty were fabricated, there would have to be a corresponding fabrication of the history of the rest of Europe during the same era, including Anglo-Saxon England, the Papacy, and the Byzantine Empire. The "phantom time" period also encompasses the life of Muhammad and the Islamic expansion into the areas of the former Western Roman Empire, including the conquest of Visigothic Iberia. This history too would have to be forged or drastically misdated. It would also have to be reconciled with the history of the Tang dynasty of China and its contact with the Islamic world, such as at the Battle of Talas.[3][6]

Bibliography

editPublications by Illig:

- Egon Friedell und Immanuel Velikovsky. Vom Weltbild zweier Außenseiter, Basel 1985.

- Die veraltete Vorzeit, Heribert Illig, Eichborn, 1988

- with Gunnar Heinsohn: Wann lebten die Pharaonen?, Mantis, 1990, revised 2003 ISBN 3-928852-26-4

- Karl der Fiktive, genannt Karl der Große, 1992

- Hat Karl der Große je gelebt? Bauten, Funde und Schriften im Widerstreit, 1994

- Hat Karl der Große je gelebt?, Heribert Illig, Mantis, 1996

- Das erfundene Mittelalter. Die größte Zeitfälschung der Geschichte, Heribert Illig, Econ 1996, ISBN 3-430-14953-3 (revised ed. 1998)

- Das Friedell-Lesebuch, Heribert Illig, C.H. Beck 1998, ISBN 3-406-32415-0

- Heribert Illig, with Franz Löhner: Der Bau der Cheopspyramide, Mantis 1998, ISBN 3-928852-17-5

- Wer hat an der Uhr gedreht?, Heribert Illig, Ullstein 2003, ISBN 3-548-36476-4

- Heribert Illig, with Gerhard Anwander: Bayern in der Phantomzeit. Archäologie widerlegt Urkunden des frühen Mittelalters., Mantis 2002, ISBN 3-928852-21-3

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hans-Ulrich Niemitz, Did the Early Middle Ages Really Exist? pp. 9–10.

- ^ Fomenko, Anatoly (2007). History: Chronology 1: Second Edition. Mithec. ISBN 978-2-913621-07-7.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b c Dutch, Stephen. "Is a Chunk of History Missing?". Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ a b Fößel, Amalie (1999). "Karl der Fiktive?". Damals, Magazin für Geschichte und Kultur. No. 8. pp. 20f. NOTE: This is just a letter to the editor with no academic references, it is not a valid refutation.

- ^ a b Karl Mütz: Die „Phantomzeit“ 614 bis 911 von Heribert Illig. Kalendertechnische und kalenderhistorische Einwände. In: Zeitschrift für Württembergische Landesgeschichte. Band 60, 2001, S. 11–23.

- ^ a b Adams, Cecil (22 April 2011). "Did the Middle Ages Not Really Happen?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Johannes Fried: Wissenschaft und Phantasie. Das Beispiel der Geschichte, in: Historische Zeitschrift Band 263,2/1996, 291–316. Matthias Grässlin, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 1. Oktober 1996

- ^ EuS 1997 Heft 4. Theo Kölzer (Bonn University) refused to contribute, and the journal printed his letter of refusal instead in which Kölzer criticizes the journal for lending credibility to Illig's "abstruse" idea. A favourable review was published by sociologist Gunnar Heinsohn, which later led to a collaboration between Illig and Heinsohn until 2011, when Heinsohn left the board of editors of Illig's journal and published his rejection of Illig's core idea that the figure of Charlemagne is a high medieval fiction.

- ^ Michael Borgolte. In: Der Tagesspiegel vom 29. Juni 1999. Stephan Matthiesen: Erfundenes Mittelalter – fruchtlose These!, in: Skeptiker 2/2001

- ^ Meister Anton, gen. Pilgram, oder Abschied vom Manierismus (2013).

- ^ Illig, Heribert (2000). Wer hat an der Uhr gedreht?. Econ Verlag. ISBN 3-548-75064-8.

- ^ Illig, Heribert (2004). Das erfundene Mittelalter. Ullstein. ISBN 3-548-36429-2.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History (Book II) Archived 2017-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 14 June 2017

- ^ Dieter Herrmann (2000), "Nochmals: Gab es eine Phantomzeit in unserer Geschichte?", Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte 3 (in German), pp. 211–14

- Illig, Heribert: Enthält das frühe Mittelalter erfundene Zeit? and subsequent discussion, in: Ethik und Sozialwissenschaften 8 (1997), pp. 481–520.

- Schieffer, Rudolf: Ein Mittelalter ohne Karl den Großen, oder: Die Antworten sind jetzt einfach, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 48 (1997), pp. 611–17.

- Matthiesen, Stephan: Erfundenes Mittelalter – fruchtlose These!, in: Skeptiker 2 (2002).