Hermogenes, son of Apollonios (Ancient Greek: Ἑρμογένης Ἀπολλωνίου) also known as Hermogenes of Xanthos (Ancient Greek: Ἑρμογένης Ξάνθιος), became a Roman citizen under the name Titus Flavius Hermogenes (Ancient Greek: Τίτος Φλάουιος Ἑρμογένης),[N 1] whose nickname was "the Horse" (ὁ Ἵππος). He was a Greek athlete from the city-state of Xanthos in Lycia, living in the 1st century AD.

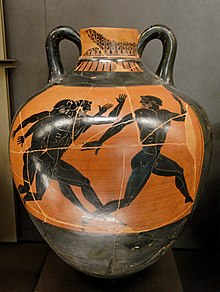

Stadion runners.

Panathenaic black-figure amphora, circa 500 B.C. Painter of Cleophrades (Louvre G65) | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | Xanthos |

| Died | Unknown |

| Occupation | Runner |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Athletics |

| Event(s) | Stadion winner at the Ancient Olympic Games (d) (81 and 89); Triastès (81 and 89); Victory at the hoplitodromos (d) (81, 85 and 89); Winner of the diaulos (d) (81, 85 and 89); Winner of the Nemean Games (d); Winner of the Pythian Games (d); Winner of the Isthmian Games (d) |

A specialist in foot racing, Hermogenes won thirty-one titles at the "periodic" Panhellenic Games, including eight at the Olympic Games. He also excelled in the numerous isolympic competitions that had multiplied by then. He thus triumphed in the race in armor at the Capitoline Games, during their recreation in Rome by Domitian in 86 AD. The emperor is said to have granted him Roman citizenship as a reward. A commemorative monument was dedicated to him, probably as early as 90 AD, at the entrance of the Letoon of Xanthos, in a place of honor.

Athlete

editHermogenes was the son of Apollonios according to the inscription on his commemorative monument in Xanthos,[1][2] or the son of Demetrios per the inscription on the winners’ list at the Sebasta (the "Augustan Games") of Neapolis.[3] According to Miranda de Martino, who analyzed the latter inscription, this discrepancy in parentage could be due to "Roman" adoption.[4] Hermogenes specialized in foot racing events and excelled in the stadion, a length of one stadium (approximately 192 m); the diaulos, a length of two stadiums (approximately 384 m); and the hoplitodromos, the armed race of two stadiums.[1][2]

Nicknamed "the Horse" (ὁ Ἵππος), Hermogenes won eight Olympic crowns during the 80s AD. He competed as a "triastes[N 2]" at the 215th and 217th Olympic Games, in 81 and 89 AD, securing victories in the stadion, diaulos, and hoplitodromos events. Despite not winning the stadion event in 85 AD, he managed to maintain his title in the other two events that year.[1][5][6][7][8][9][10] Luigi Moretti suggests that victories in different events such as the dolichos (long-distance race) or the pentathlon would not be excluded: a stadion runner, therefore a sprinter, could possess the necessary skills for such competitions.[10]

He is credited with five victories at the Pythian Games, nine victories at the Isthmian Games, and nine others at the Nemean Games. He also won the armed race at the Capitoline Games during their recreation (modeled after the Olympic Games) by Domitian in Rome in 86.[7][11][12][N 3] In other isolympic competitions, he achieved seven victories (called "shields") at the Heraia of Argos, five victories at the games of Pergamon (games of the Asian koinon[N 4]), five at the Balbillea (Ephesus), four at the Actia (Nicopolis), four[N 5] at the Sebasta (the "Augustan Games") of Neapolis, four at the games of Smyrna (games of the Asian koinon), four at the games of Syria, Cilicia, and Phoenicia (celebrated in Antioch as part of the imperial cult), three at the Sebasta of Alexandria, as well as in "many other competitions.[N 6]"[12][13][14]

Hermogenes won the "armed race from the trophy" at the Eleutheria of Plataea, celebrating the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC. This race, longer than a usual hoplitodromos (two stades), spanned approximately fifteen stades from the battlefield trophy to the city’s altar of Zeus Eleutherios ("Zeus the Liberator"). The champion was hailed as the "best among the Greeks."[12][14][15]

Honors

editHermogenes, a citizen of Xanthos, was granted Roman citizenship as a reward for his victory at the Capitoline Games by one of the Flavian emperors, likely Domitian. This is indicated by his choice of praenomen (Titus, one of Domitian's names) and gentilicium (Flavius). The inscription on the commemorative monument at the Letoon of Xanthos also reveals that Hermogenes was a citizen of Patara (a neighboring Lycian city closely linked to Xanthos), Alexandria[N 7] (specifically mentioned as a prestigious city), as well as "in all the most eminent cities of Asia and Greece[N 8]," likely due to his success in games held in those cities, which often led to the granting of citizenship.[7][11][12]

He also held the title of paradoxonikès, "extraordinary victor." This term was originally used for athletes who achieved victory despite all odds being against them. It was specifically given to athletes who won both wrestling and pankration on the same day at the same games, making them successors of Heracles. The title also extended to athletes who won two or three victories at the same games.[11][12][16]

A complex monument dedicated to Hermogenes was erected in his honor, possibly around 90 AD, at the entrance of the Letoon of Xanthos. The Letoon was the federal sanctuary of the Lycian Confederation. The monument, measuring 3.60 meters in length and approximately 1 to 1.40 meters in height with a width of just over 90 centimeters, comprised four inscribed pedestals with two bronze statues at each end. The statue nearest to the propylaeum entrance of the sanctuary portrayed a running athlete in a welcoming pose to visitors or pilgrims in a three-quarter view.[17]

After his victories, the emperor[N 9] appointed him xystarch for life for all the games organized in his native Lycia.[1][7][18] This position, named after the xystos, the covered part of the gymnasium where athletes could train in winter, referred in Roman times to the president of an association of athletes and, by extension, the organizer of games.[18][19] Only the emperor could appoint a xystarch. Typically, the position was limited to a single city, but Hermogenes' responsibilities extended to an entire province, which was very rare and a testament of his great renown.[18]

Annexes

editAncient literary sources

edit- Eusebius. Chronicle. Vol. I. pp. 70–82.

- Pausanias. Description de la Grèce (in French). pp. 6, 13, 3.

Bibliography

edit- Balland, André; Le Roy, Christian (1984). "Le Monument de Titus Flavius Hermogénès au Létoon de Xanthos". Revue Archéologique (in French). 2: 325–349.

- Christesen, Paul (2007). Olympic Victor Lists and Ancient Greek History. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86634-7.

- Decker, Wolfgang (2014). Antike Spitzensportler : Athletenbiographien aus dem Alten Orient, Ägypten und Griechenland (in German). Hildesheim: Arete Verlag. ISBN 978-3-942468-23-7.

- Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24881-7.

- Harris, Harold Arthur (1964). Greek athletes and athletics. London: Hutchinson.

- Miranda de Martino, Elena (2013). "Ritratti di Campioni dai Sebastà di Napoli". Mediterraneo Antico (in Italian). XVI (II): 519–536.

- Matz, David (1991). Greek and Roman Sport : A Dictionnary of Athletes and Events from the Eighth Century B. C. to the Third Century A. D. Jefferson and London: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-89950-558-9.

- Moretti, Luigi (1959). Olympionikai, i vincitori negli antichi agoni olimpici (in Italian). Vol. VIII. Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. pp. 55–199.

- Pleket, H. W; Stroud, R. S (1984). "SEG 34-1314-1317. Xanthos. Monument for the athlete Titus Flavius Hermogenes, ca 90 A.D.". Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. doi:10.1163/1874-6772_seg_a34_1314_1317.

External links

edit- Sport resource (in French): Olympedia

Notes and references

editNotes

edit- ^ This athlete was previously known as "Hermogenes of Xanthos," in the stadion winners’ lists compiled by Julius Africanus and Eusebius of Caesarea. However, the discovery of the monument dedicated to him at the Letoon of Xanthos in 1981-1982 revealed his chosen Roman citizen name as: "Titus Flavius Hermogenes," along with his father's name.

- ^ Title awarded to an athlete who won three victories during the same games. Only eight (all runners) are known for the ancient Olympic Games (Golden 2004, p. 168).

- ^ Elena Miranda de Martino suggests a later victory, around 94 or 98 (Miranda de Martino 2013, p. 529).

- ^ The term "koinon," sometimes translated as "confederation," "league," or "assembly," refers to a political grouping of cities, often on a regional scale. These structures proliferated during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. (Amouretti, Marie-Claire; Ruzé, Françoise (1978). Le monde grec antique : des palais crétois à la conquête romaine (in French). Paris: Hachette Livre. pp. 208, 209, 239. ISBN 2010074971.)

- ^ Stadion, diaulos, and hoplitidromos in 86 and hoplitodromoes in 90 or 94 (Miranda de Martino 2013, pp. 526–528).

- ^ Common generic formula (Balland & Le Roy 1984, p. 346).

- ^ He may have obtained it between his first victories at Neapolis in 86 and his victory in 90 or 94, because he is listed in 86 as a citizen of Xanthos and, in 90 or 94, as a citizen of both Xanthos and Alexandria (Miranda de Martino 2013, p. 528).

- ^ Generic formula without specific institutional significance (Balland & Le Roy 1984, p. 343).

- ^ His name is also not specified in the inscription. It could be Domitian, the very emperor who granted him citizenship.

References

edit- ^ a b c d Decker 2014, p. 130

- ^ a b Balland & Le Roy 1984, p. 341

- ^ Miranda de Martino 2013, pp. 526–528

- ^ Miranda de Martino 2013, p. 528

- ^ Balland & Le Roy 1984, p. 342

- ^ Harris 1964, p. 65

- ^ a b c d Golden 2004, p. 68

- ^ Matz 1991, pp. 64 and126

- ^ Miranda de Martino 2013, p. 526-530

- ^ a b Moretti 1959, p. 159-160 (notes 805-807, 812-813 and 817-819).

- ^ a b c Balland & Le Roy 1984, p. 343

- ^ a b c d e Decker 2014, pp. 130–131

- ^ Balland & Le Roy 1984, pp. 344–346

- ^ a b Miranda de Martino 2013, p. 529

- ^ Balland & Le Roy 1984, pp. 343–344

- ^ Golden 2004, pp. 128–129

- ^ Balland & Le Roy 1984, pp. 325, 333, 336–338, 342

- ^ a b c Balland & Le Roy 1984, p. 344

- ^ Golden 2004, p. 178