The Hidden Fortress (Japanese: 隠し砦の三悪人, Hepburn: Kakushi Toride no San Akunin, lit. 'The Three Villains of the Hidden Fortress') is a 1958 Japanese jidaigeki[5] adventure film directed by Akira Kurosawa, with special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya. It tells the story of two peasants who agree to escort a man and a woman across enemy lines in return for gold without knowing that he is a general and the woman is a princess. The film stars Toshiro Mifune as General Makabe Rokurōta and Misa Uehara as Princess Yuki while the peasants, Tahei and Matashichi, are portrayed by Minoru Chiaki and Kamatari Fujiwara respectively.

| The Hidden Fortress | |

|---|---|

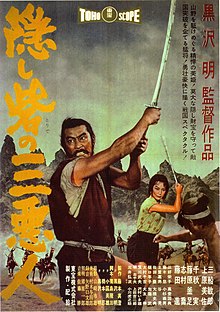

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ichio Yamazaki[1] |

| Edited by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Music by | Masaru Sato[1] |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 139 minutes[2] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | ¥195 million[3] |

| Box office | ¥342.64 million[4] |

The Hidden Fortress was the fourth highest-grossing film of the year in Japan, and Kurosawa's most successful film up to that point. It was a significant influence on the 1977 American film Star Wars.[6]

Plot

editTwo bedraggled peasants, Tahei and Matashichi, sell their homes and leave to enlist with the feudal Yamana clan, hoping to make their fortunes as soldiers. Instead, they are mistaken for soldiers of the defeated Akizuki clan, have their weapons confiscated, and are forced to help dig graves before being sent away without any food. After quarrelling and splitting up, the two are each captured again and reunited when the Yamana force them alongside dozens of other prisoners to dig through the ruins of the Akizuki castle for the clan's secret reserve of gold. After a prisoner uprising, Tahei and Matashichi slip away, steal some rice, and make camp near a river.

While building a fire, they find a piece of gold marked with the crescent of the Akizuki clan hidden in a hollowed-out stick. Looking for more of the gold, the peasants are discovered by a mysterious man whom they take to be a bandit. They explain how they intend to escape Yamana territory: rather than cross the closely-guarded border into the neighboring state of Hayakawa, they will travel to Yamana itself and then pass into Hayakawa. The stranger is enthused by their plan, so he shows them another piece of gold, and he leads them to a secret camp in the mountains where the rest is hidden. Unbeknownst to them, the man is a famous Akizuki general, Makabe Rokurōta. Although Rokurōta initially planned to kill the peasants, he changes his mind and decides to use their plan to bring the gold and Princess Yuki of the Akizuki clan, also hidden in the camp, to Hayakawa, whose lord has promised to protect them.

Rokurōta escorts Princess Yuki and the huge cache, 200 kan of the clan's gold (still hidden in hollowed-out logs of wood), to Yamana, bringing Matashichi and Tahei to help carry the gold but kept unaware of Yuki and Rokurōta's identities. To protect Yuki, he has her pretend to be a deaf-mute and has a decoy (Rokurōta's younger sister) sent to the Yamana to be executed so they will believe that she is dead. During their travels, Tahei and Matashichi get the group into dangerous situations several times owing to their cowardice and greed. During a stop for the night at an inn, Yuki forces Rokurōta to buy the freedom of a captive young woman who had belonged to the Akizuki clan, who then refuses to leave them.

After losing their horses and obtaining a cart to move the gold, the group is spotted by a Yamana patrol, and Rokurōta is forced to kill them. While pursuing two stragglers, he accidentally rides into a Yamana camp, where the commanding officer, Rokurōta's old rival Hyoe Tadokoro, recognizes him. Tadokoro is sorry he didn't get to face Rokurōta in battle and challenges him to a lance duel. Rokurōta wins, but spares Tadokoro's life before stealing a horse and riding back to the group. While in Yamana, they see worshippers gathering for the Fire Festival, so Tahei and Matashichi decide to hide the load of wood among them, but, since they are under the eyes of the Yamana soldiers, they are forced to throw the cart onto the bonfire and join in the ritual dance. Princess Yuki is quite taken by the philosophy behind the Festival regarding the shortness of life and the pettiness of the world. The next day they dig the gold out of the fire's remains and take away as much as they can carry. One night as they approach the Hayakawa border, they are surrounded. Matashichi and Tahei manage to hide in the confusion while the rest are captured by Yamana soldiers and detained at an outpost. The two of them try to turn in Rokurōta for a reward, but having already captured them, the soldiers laugh at them and they leave for Hayakawa with nothing.

Tadokoro comes to identify the prisoners the night before their execution. Tadokoro's face is now disfigured by a large scar which he explains is the result of a beating ordered by the Yamana lord, as punishment for letting Rokurōta escape. Yuki proclaims that she has no fear of death and thanks Rokurōta for letting her see humanity's ugliness and beauty from a new perspective, and she repeats the ritual chant from the Fire Festival. The next day, as the soldiers start marching the prisoners to be executed, Tadokoro begins singing the same chant, and suddenly sends the horses carrying the gold running across the border. He frees the prisoners and distracts the guards so they can ride off, but Yuki tells him to join them. The entire group manages to escape across the border into Hayakawa.

Matashichi and Tahei, both hungry and tired, stumble across the lost gold carried by the horses and immediately start arguing about dividing it between them, before being arrested by Hayakawa soldiers as thieves. The peasants are brought before an armoured samurai and a well-dressed noblewoman. General Rokurōta and Princess Yuki finally reveal their identities to the astonished peasants. Thanking them for saving the gold (which will be used to restore her clan), the princess rewards Matashichi and Tahei with a single ryō on the condition that they share it. As the two men leave the castle to walk back to their village, they begin to laugh upon realizing that they have finally made their fortunes.

Cast

edit- Toshiro Mifune as General Rokurota Makabe (真壁 六郎太, Makabe Rokurota)

- Minoru Chiaki as Tahei

- Kamatari Fujiwara as Matashichi

- Susumu Fujita as General Hyoe Tadokoro (田所 兵衛, Tadokoro Hyoe)

- Takashi Shimura as General Izumi Nagakura (長倉 和泉, Nagakura Izumi)

- Misa Uehara as Princess Yuki

- Eiko Miyoshi as Yuki's lady-in-waiting

- Toshiko Higuchi as a prostitute purchased by the group who chooses to accompany them

- Yū Fujiki as a Yamana soldier

- Sachio Sakai as a samurai

- Yoshio Tsuchiya as a Yamana samurai

- Kokuten Kōdō as an old villager who tells Matashichi about a reward for Yuki's capture

- Kōji Mitsui as a Yamana guard overseeing the excavation of Akizuki Castle

Production

editThe Hidden Fortress was Kurosawa's first feature filmed in a widescreen format, Tohoscope, which he continued to use for the next decade. The film was originally presented with Perspecta directional sound, which was re-created for the Criterion Blu-ray release.[7]

Key parts of the film were shot in Hōrai Valley in Hyōgo and on the slopes of Mt. Fuji, where bad weather from the record-breaking Kanagawa typhoon delayed the production. Toho's frustration with Kurosawa's slow pace of shooting led to the director forming his own production company the following year, though he continued to distribute through Toho.[8]

Music

edit| The Hidden Fortress | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1958 |

| Genre | Feature film soundtrack |

| Length | 74:04 |

| Label | Toho Music |

The film's musical score was composed by Masaru Sato. The soundtrack album comprises 65 tracks.[9][10]

Tracks

edit- Titles

- Fallen Warrior's Death

- Peaceful Mountain Pass Road

- Yamana: Temporary Checkpoint

- War town ~ To the border

- Prisoner's loss of dignity

- Burnt Ruins of Autumn Moon Castle

- Flight

- Money!!!

- Mysterious Mountain Man 1

- Mysterious Mountain Man 2

- Good idea to go cross country

- Shining Extended Staff

- Road to the Hidden Fortress

- Woman on the Summit

- Useless Work

- Spring Woman

- Escaping Woman

- Reward Money

- Rokurota, to the Cave

- Princess Yuki's tears

- Horse and Princess

- Riding in the indicated direction

- Setting off

- Gestured Excuse

- Rokurota's Scouting

- Reliable Ally 1

- Reliable Ally 2

- Over the Black Smoke

- Bolder Trick

- Into the cheap lodgings

- Autumn Moon Woman

- Princess Yuki's Wish

- Adept on Horseback

- Spear March

- Departing Rokurota

- Party's true shape

- Daughter and Rokurota

- Sleeping Princess

- Line of Firefighters

- Surprising Rokurota (unused)

- Introduction to Firefighters

- Firefighters

- Highland Hauting

- Going Downhill

- Coming to the same conclusion

- To Hayawaka Territory

- Matashichi and Peace, In the checkpoint

- Firefighter's Song

- Execution Draws Near

- Treasonous Pardon ~ Pass Crossing

- Two Bad men in prison

- Reunion in a Castle

- Reward

- Ending

- Castle Town (ambient sounds 1)

- Castle Town (ambient sounds 2)

- Child Song

Alternative Takes

- Titles

- Escaping Woman

- Adept on Horseback

- Departing Rokurota (alt take 1)

- Departing Rokurota (alt take 2)

- To Hayawaka Territory

- Reunion in a Castle

Release

editThe Hidden Fortress was released theatrically in Japan on December 28, 1958.[2] The film was the highest-grossing film for Toho in 1958, ranking as the fourth highest-grossing film overall in Japan that year.[2] In box-office terms, The Hidden Fortress was Kurosawa's most successful film, until the 1961 release of Yojimbo.[5]

The film was released theatrically in the United States by Toho International Col. with English subtitles.[2] It was screened in San Francisco in November 1959 and received a wider release on October 6, 1960, with a 126-minute running time.[2] The film was re-issued in the United States in 1962 with a 90-minute running time.[2] The film was compared unfavorably to Rashomon (1950) and Seven Samurai (1954), and performed poorly at the U.S. box office.[11]

Critical reception

editIn a 1957 review, Variety called it "a long, interesting, humour-laden picture in medieval Japan". Performances of the lead actors, Kurosawa's direction and Ichio Yamazaki's camerawork were praised.[12]

An article published in The New York Times on January 24, 1962, featured a review of the film by journalist Bosley Crowther, who called The Hidden Fortress a superficial film. He said that Kurosawa, "the Japanese director whose cinema skills have been impressed upon us in many pictures, beginning with "Rashomon", is obviously not above pulling a little wool over his audiences' eyes — a little stooping to Hollywoodisms — in order to make a lively film." Crowther further opined that "Kurosawa, for all his talent, is as prone to pot boiling as anyone else."[13]

Writing for The Criterion Collection in 1987, David Ehrenstein called it "one of the greatest action-adventure films ever made" and a "fast-paced, witty and visually stunning" samurai film. According to Ehrenstein:

The battle on the steps in Chapter 2 (anticipating the climax of Ran) is as visually overwhelming as any of the similar scenes in Griffith's Intolerance. The use of composition in depth in the fortress scene in Chapter 4 is likewise as arresting as the best of Eisenstein or David Lean. Toshiro Mifune's muscular demonstrations of heroic derring-do in the horse-charge scene (Chapter 11) and the scrupulously choreographed spear duel that follows it (Chapter 12) is in the finest tradition of Douglas Fairbanks. Overall, there’s a sense of sheer "movieness" to The Hidden Fortress that places it plainly in the ranks of such grand adventure entertainments as Gunga Din, The Thief of Baghdad, and Fritz Lang's celebrated diptych The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Hindu Tomb.[14]

David Parkinson of the Empire on a review posted on January 1, 2000, gave the film four out of five stars and wrote "Somewhat overshadowed by the likes of Seven Samurai, this is a vigorously placed, meticulously staged adventure. It's not top drawer, but still ranks among the best of Kurosawa's minor masterpieces."[15]

Writing for The Criterion Collection in 2001, Armond White said "The Hidden Fortress holds a place in cinema history comparable to John Ford's Stagecoach: It lays out the plot and characters of an on-the-road epic of self-discovery and heroic action. In a now-familiar fashion, Rokurōta and Princess Yuki fight their way to allied territory, accompanied by a scheming, greedy comic duo who get surprised by their own good fortune. Kurosawa always balances valor and greed, seriousness and humor, while depicting the misfortunes of war."[5]

Upon the film's UK re-release in 2002, Jamie Russell, reviewing the film for the BBC, said it "effortlessly intertwines action, drama, and comedy", calling it "both cracking entertainment and a wonderful piece of cinema."[16]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian made a review on February 1, 2002. According to him:

Revered now as an inspiration for George Lucas, Kurosawa's amiable, forthright epic romance happens on a scorched, rugged landscape which looks quite a lot like an alien planet. At other times, the movie plays like nothing so much as a roistering comedy western. But it has a cleverly contrived relationship between the principals, including a fantastically brash and virile Toshiro Mifune. The comedy co-exists with a dark view of life's brevity, and Kurosawa devises exhilarating setpieces and captivating images. Arthouse classics aren't usually as welcoming and entertaining as this.[17]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 96% based on 51 critic reviews, with the consensus, "A feudal adventure told from an eccentric perspective, The Hidden Fortress is among Akira Kurosawa's most purely enjoyable epics."[18]

Awards

editThe film won the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 9th Berlin International Film Festival in 1959.[2][19] Kinema Junpo awarded Shinobu Hashimoto the award for Best Screenwriter for his work on the film and for Tadashi Imai's Night Drum and Yoshitaro Nomura's Harikomi.[2]

Legacy

editInfluence

editAmerican director George Lucas has acknowledged the heavy influence of The Hidden Fortress on his 1977 film Star Wars,[20][21][22] particularly in the technique of telling the story from the perspective of the film's lowliest characters, C-3PO and R2-D2.[23][24] Some of the major characters from Star Wars have clear analogues in The Hidden Fortress, including C-3PO and R2-D2 being based on Tahei and Matashichi, and Princess Leia on Princess Yuki. Lucas's original plot outline for Star Wars bore an even greater resemblance to the plot of The Hidden Fortress;[25] this draft would subsequently be reused as the basis for The Phantom Menace. The movie is referenced in Lego Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga, where during a cutscene for the first level of Return of the Jedi, there is a flag written in Aurebesh, which translates to "Hidden Fortress".

A number of plot elements from The Hidden Fortress are used in the 2006 video game Final Fantasy XII.[26][27]

Remake

editA loose remake entitled Hidden Fortress: The Last Princess was directed by Shinji Higuchi and released on May 10, 2008.

References

edit- ^ a b c d Galbraith IV 2008, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Galbraith IV 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Shiozawa 2005, p. 92.

- ^ Kinema Junpo 2012, p. 148.

- ^ a b c White, Armond (May 21, 2001). "The Hidden Fortress". Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on 2012-12-28. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ^ Young, Bryan (2019-07-23). "'Star Wars' Owes A Great Debt To Akira Kurosawa's 'The Hidden Fortress'". SlashFilm.com. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Stuart Galbraith IV (March 18, 2014). "The Hidden Fortress (Criterion Collection) (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan, 130-31, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.

- ^ World of Soundtrack (3 May 2009). "Masaru Sato — The Hidden Fortress". Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "The Hidden Fortress". Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Nollen, Scott Allen (14 March 2019). 1958 The Hidden Fortress. McFarland. ISBN 9781476670133. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Variety (January 1958). "Variety reviews The Hidden Fortress". variety.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ NYTimes (24 January 1962). "Screen:'Hidden Fortress' from Japan:Kurosawa Resorts to Hollywood Effects Also Pulls Little Wool Over Viewers' Eyes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Ehrenstein, David (October 12, 1987). "The Hidden Fortress". Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on 2012-12-28. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ^ Empire (1 January 2000). "The Hidden Fortress review by The Empire". empireonline.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Russell, Jamie (31 January 2002). "The Hidden Fortress (Kakushi Toride No San Akumin) (1958)". BBC. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ^ The Guardian (1 February 2002). "The Hidden Fortress: The comedy co-exists with a dark view of live's brevity, and Kurosawa devises exhilarating setpieces and captivating images". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes. "The Hidden Fortress Review". rottentomatoes.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Berlinale: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ Kaminski, Michael (2012). "Under the Influence of Akira Kurosawa: The Visual Style of George Lucas". In Brode, Douglas; Deyneka, Leah (eds.). Myth, Media, and Culture in Star Wars: An Anthology. Scarecrow Press. pp. 83–99. ISBN 978-0-8108-8512-7.

- ^ Martinez, D. P. (2009). "Cloning Kurosawa". Remaking Kurosawa. pp. 161–171. doi:10.1057/9780230621671_10. ISBN 978-0-312-29358-1.

- ^ Kaminski, Michael (2008). The Secret History of Star Wars: The Art of Storytelling and the Making of a Modern Epic. Legacy Books Press. ISBN 978-0-9784652-3-0.[page needed]

- ^ Star Wars DVD audio commentary

- ^ Kaminski, Michael (2008). The Secret History of Star Wars: The Art of Storytelling and the Making of a Modern Epic. Legacy Books Press. ISBN 978-0-9784652-3-0.[page needed]

- ^ Stempel, Tom (2000). Framework: A History of Screenwriting in the American Film, Third Edition. Syracuse University Press. pp. 154, 204. ISBN 978-0-8156-0654-3.

- ^ "Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age - Review". 10 July 2017. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Final Fantasy 12 the Zodiac Age review - A chance to revisit a much-overlooked classic". July 23, 2017. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

Sources

edit- Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-1-4766-8674-5.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1461673743. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- "Kinema Junpo Best Ten 85th Complete History 1924-2011". Kinema Junpo (in Japanese). May 17, 2012. ISBN 9784873767550.

- Shiozawa, Yukito (July 2005). "Kurosawa" Movie Art Edition (in Japanese). Marikasha. ISBN 978-4309906447.

Further reading

edit- Martinez, Dolores P. (2023-02-22). "Scaling up? Remaking Kurosawa's The Three Villains of the Hidden Fortress". Japan Forum. 35 (1): 54–75. doi:10.1080/09555803.2022.2152472.

External links

edit- The Hidden Fortress at IMDb

- The Hidden Fortress at AllMovie

- The Hidden Fortress at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Hidden Fortress (in Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

- The Hidden Fortress: Three Good Men and a Princess an essay by Catherine Russell at the Criterion Collection