Hillabee was an important Muscogee (Creek) town in east central Alabama before the Indian Removals of the 1830s.

Hillabee was the center of a cluster of towns and villages, known as the Hillabee complex or, simply, Hillabee. The people living in the Hillabee complex area are sometimes called the Hillabees. That name does not refer to a separate tribe or clan but merely those Muscogees who lived in the Hillabee complex area.[2][3]

The word "Hillabee" comes from the Muscogee language word helvpe /hílapi/, meaning quick or swift, perhaps referring to the streams in the area.[3][4]

Location

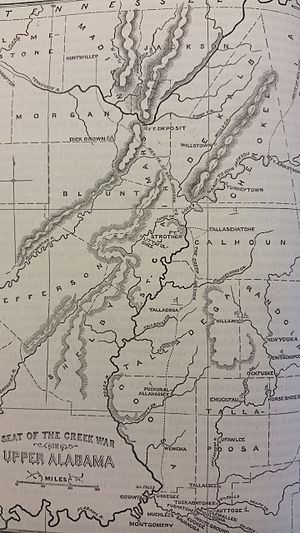

editHillabee and its satellite villages were located along Little Hillabee Creek and Enitachopco Creek where they join to form Big Hillabee Creek. Villages within the complex, along these streams, included Echoseis Ligau, Enitachopko, Lanudshi Apala, and Oktasassi.[2] Nearby towns and villages associated with Hillabee include Oakfuskee, Little Oakfuskee, and Atchinalgi.[3]

Today the area is in southern Clay County and northern Tallapoosa County, north of Alexander City. The present-day villages of Millerville and Bluff Springs lie within the former Hillabee complex area.[2]

History

editThe Hillabee complex, focused along the Hillabee and Enitachopco Creeks, dates back at least to the late 17th century. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries the complex lay in the approximate center of the Creek Confederacy's territory. Its population probably peaked after the Creek War (1813–14), then declined. Creek settlement in the area ended with the forced removal of the Muscogee people during the 1830s.[2]

During the Creek War, part of the War of 1812, the Muscogee (Creek) people were divided. Those who fought against the United States were known as the Red Sticks. The Hillabee people had been Red Stick allies until the Battle of Tallushatchee and Battle of Talladega.[5] A large number of Hillabee Creeks fought General Andrew Jackson's forces at Talladega. They were badly defeated and sued for peace, which Jackson granted on 17 November 1813. One day later the Hillabee villages were attacked by troops under General William Cocke, who did not know about the peace. The villages of Little Oakfusky and Genalga were completely destroyed. Then main town of Hillabee was attacked. The Creeks, who thought they were at peace, were completely surprised and gave little resistance. During the attack 64 Creek were killed, 29 wounded, and 237 taken captive and sent to Fort Armstrong, near Turkeytown. Feeling betrayed, the Hillabees returned to the Red Stick alliance and remained bitter enemies of the Americans for the rest of the war.[6]

The complex was located near the junction of several important trading trails, notably the Oakfuskee Trail (Upper Creek Trading Path), the Weogulfga-Oakfuskee Trail, and the Cussetta Trading Path. After the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson the United States and white settlers build or improved a number of roads crossing Creek lands. Roads that crossed the Hillabee area included the McIntosh Road (also called the Georgia Road), which connected Coweta to Talladega, the Federal Road, which connected Milledgeville, to Mobile, and was originally an Indian trail called the Three Notch Road. Part of the Weogulfga-Oakfuskee Trail near Hillabee was widened and became known as the Chapman Road.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 778.

- ^ a b c d East, Don C. (2 December 2008). A Historical Analysis of the Creek Indian Hillabee Towns: And Personal Reflections on the Landscape and People of Clay County, Alabama. iUniverse. pp. xxiii–xxiv, 3. ISBN 978-1-4401-0162-5.

- ^ a b c East, Don C. (2008). A Historical Analysis of the Creek Indian Hillabee Towns: And Personal Reflections on the Landscape and People of Clay County, Alabama. iUniverse. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1-4401-0162-5.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4.

- ^ Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T. (2002). The War of 1812. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-313-31687-6.

- ^ Vining, John Eric (2010). The Trans-Appalachian Wars, 1790-1818: Pathways to America's First Empire. Trafford Publishing. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-1-4269-7964-4.

- ^ East (2008), pp. 64–66

External links

edit- The Creek War in Alabama, An ABPP Case Study, LAMAR Institute Publication Series Report Number 116, The LAMAR Institute, Inc., 2007.

- Indian Villages and Forts of the Coosa-Tallapoosa River Region

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hillabi (historical)