Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an abnormal clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, abnormal cells deriving from bone marrow and capable of migrating from skin to lymph nodes.

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | |

|---|---|

| |

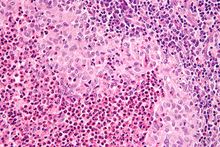

| Micrograph showing a Langerhans cell histiocytosis with the characteristic reniform Langerhans cells accompanied by abundant eosinophils. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

Symptoms range from isolated bone lesions to multisystem disease.[1] LCH is part of a group of syndromes called histiocytoses, which are characterized by an abnormal proliferation of histiocytes (an archaic term for activated dendritic cells and macrophages).[2] These diseases are related to other forms of abnormal proliferation of white blood cells, such as leukemias and lymphomas.[3]

The disease has gone by several names, including Hand–Schüller–Christian disease, Abt-Letterer-Siwe disease, Hashimoto-Pritzker disease (a very rare self-limiting variant seen at birth) and histiocytosis X, until it was renamed in 1985 by the Histiocyte Society.[4][1]

Classification

edit| Alternative names |

|---|

| Histiocytosis X

Histiocytosis X syndrome |

| Subordinate terms |

| Hand-Schüller-Christian disease

Letterer-Siwe disease |

The disease spectrum results from clonal accumulation and proliferation of cells resembling the epidermal dendritic cells called Langerhans cells, sometimes called dendritic cell histiocytosis. These cells in combination with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and normal histiocytes form typical LCH lesions that can be found in almost any organ.[5] A similar set of diseases has been described in canine histiocytic diseases.[6]

LCH is clinically divided into three groups: unifocal, multifocal unisystem, and multifocal multisystem.[7]

Unifocal

editUnifocal LCH, also called eosinophilic granuloma (an older term which is now known to be a misnomer), is a disease characterized by an expanding proliferation of Langerhans cells in one organ, where they cause damage called lesions. It typically has no extraskeletal involvement, but rarely a lesion can be found in the skin, lungs, or stomach. It can appear as a single lesion in an organ, up to a large quantity of lesions in one organ. When multiple lesions are scattered throughout an organ, it can be called a multifocal unisystem variety. When found in the lungs, it should be distinguished from Pulmonary Langerhans cell hystiocytosis—a special category of disease most commonly seen in adult smokers.[8] When found in the skin it is called cutaneous single system Langerhans cell LCH. This version can heal without therapy in some rare cases.[9] This primary bone involvement helps to differentiate eosinophilic granuloma from other forms of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe or Hand-Schüller-Christian variant).[10]

Multifocal unisystem

editSeen mostly in children, multifocal unisystem LCH is characterized by fever, bone lesions and diffuse eruptions, usually on the scalp and in the ear canals. 50% of cases involve the pituitary stalk, often leading to diabetes insipidus. The triad of diabetes insipidus, exophthalmos, and lytic bone lesions is known as the Hand-Schüller-Christian triad. Peak onset is 2–10 years of age.[11]

Multifocal multisystem

editMultifocal multisystem LCH, also called Letterer-Siwe disease, is an often rapidly progressing disease in which Langerhans cells proliferate in many tissues. It is mostly seen in children under age 2, and the prognosis is poor: even with aggressive chemotherapy, the five-year survival is only 50%.[12]

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH)

editPulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) is a unique form of LCH in that it occurs almost exclusively in cigarette smokers. It is now considered a form of smoking-related interstitial lung disease. PLCH develops when an abundance of monoclonal CD1a-positive Langerhans (immature histiocytes) proliferate the bronchioles and alveolar interstitium, and this flood of histiocytes recruits granulocytes like eosinophils and neutrophils and agranulocytes like lymphocytes further destroying bronchioles and the interstitial alveolar space that can cause damage to the lungs.[13] It is hypothesized that bronchiolar destruction in PLCH is first attributed to the special state of Langerhans cells that induce cytotoxic T-cell responses, and this is further supported by research that has shown an abundance of T-cells in early PLCH lesions that are CD4+ and present early activation markers.[14] Some affected people recover completely after they stop smoking, but others develop long-term complications such as pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension.[15]

Signs and symptoms

editLCH provokes a non-specific inflammatory response, which includes fever, lethargy, and weight loss. Organ involvement can also cause more specific symptoms.

- Bone: The most-frequently seen symptom in both unifocal and multifocal disease is painful bone swelling. The skull is most frequently affected, followed by the long bones of the upper extremities and flat bones. Infiltration in hands and feet is unusual. Osteolytic lesions can lead to pathological fractures.[16]

- Skin: Commonly seen are a rash which varies from scaly erythematous lesions to red papules pronounced in intertriginous areas. Up to 80% of LCH patients have extensive eruptions on the scalp.

- Bone marrow: Pancytopenia with superadded infection usually implies a poor prognosis. Anemia can be due to a number of factors and does not necessarily imply bone marrow infiltration.

- Lymph node: Enlargement of the liver in 20%, spleen in 30% and lymph nodes in 50% of Histiocytosis cases.[17]

- Endocrine glands: Hypothalamic pituitary axis commonly involved.[18] Central Diabetes insipidus can be the first manifestation of LCH.[19] [20]Anterior pituitary hormone deficiency is usually permanent.[21]

- Lungs: some patients are asymptomatic, diagnosed incidentally because of lung nodules on radiographs; others experience chronic cough and shortness of breath.[22]

- Less frequently gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and oral cavity.[23]

Pathophysiology

editThe pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a matter of debate. There are ongoing investigations to determine whether LCH is a neoplastic (cancerous) or reactive (non-cancerous) process. Arguments supporting the reactive nature of LCH include the occurrence of spontaneous remissions, the extensive secretion of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and bystander-cells (a phenomenon known as cytokine storm) in the lesional tissue, favorable prognosis and relatively good survival rate in patients without organ dysfunction or risk organ involvement.[24][25]

On the other hand, the infiltration of organs by monoclonal population of pathologic cells, and the successful treatment of subset of disseminated disease using chemotherapeutic regimens are all consistent with a neoplastic process.[26][27][28] In addition, a demonstration, using X chromosome–linked DNA probes, of LCH as a monoclonal proliferation provided additional support for the neoplastic origin of this disease.[29] While clonality is an important attribute of cancer, its presence does not prove that a proliferative process is neoplastic. Recurrent cytogenetic or genomic abnormalities would also be required to demonstrate convincingly that LCH is a malignancy.[30]

An activating somatic mutation of a proto-oncogene in the Raf family, the BRAF gene, was detected in 35 of 61 (57%) LCH biopsy samples with mutations being more common in patients younger than 10 years (76%) than in patients aged 10 years and older (44%).[31] This study documented the first recurrent mutation in LCH samples. Two independent studies have confirmed this finding.[32][33] Presence of this activating mutation could support the notion to characterize LCH as myeloproliferative disorder.

Diagnosis

editDiagnosis is confirmed histologically by tissue biopsy. Hematoxylin-eosin stain of biopsy slide will show features of Langerhans Cell e.g. distinct cell margin, pink granular cytoplasm.[34] Presence of Birbeck granules on electron microscopy and immuno-cytochemical features e. g. CD1 positivity are more specific. Initially routine blood tests e.g. full blood count, liver function test, U&Es, bone profile are done to determine disease extent and rule out other causes.[35]

Imaging may be evident in chest X-rays with micronodular and reticular changes of the lungs with cyst formation in advanced cases. MRI and High-resolution CT may show small, cavitated nodules with thin-walled cysts. MRI scan of the brain can show three groups of lesions such as tumourous/granulomatous lesions, nontumourous/granulomatous lesions, and atrophy. Tumourous lesions are usually found in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis with space-occupying lesions with or without calcifications. In non-tumourous lesions, there is a symmetrical hyperintense T2 signal with hypointense or hyperintense T1 signal extending from grey matter into the white matter. In the basal ganglia, MRI shows a hyperintense T1 signal in the globus pallidus.[36]

Assessment of endocrine function and bone marrow biopsy are also performed when indicated.[37]

- S-100 protein is expressed in a cytoplasmic pattern[38][39]

- peanut agglutinin (PNA) is expressed on the cell surface and perinuclearly[40][41]

- major histocompatibility (MHC) class II is expressed (because histiocytes are macrophages)

- CD1a[38]

- langerin (CD207), a Langerhans Cell–restricted protein that induces the formation of Birbeck granules and is constitutively associated with them, is a highly specific marker.[42][43]

Treatment

editGuidelines for management of patients up to 18 years with Langerhans cell histiocytosis have been suggested.[44][45][46][47] Treatment is guided by extent of disease. Solitary bone lesion may be amenable through excision or limited radiation, dosage of 5-10 Gy for children, 24-30 Gy for adults. However systemic diseases often require chemotherapy. Use of systemic steroid is common, singly or adjunct to chemotherapy. Local steroid cream is applied to skin lesions. Endocrine deficiency often require lifelong supplement e.g. desmopressin for diabetes insipidus which can be applied as nasal drop. Chemotherapeutic agents such as alkylating agents, antimetabolites, vinca alkaloids either singly or in combination can lead to complete remission in diffuse disease.[citation needed]

Prognosis

editThere is a general excellent prognosis for the disease as those with localized disease have a long life span. With multi-focal disease 60% have a chronic course, 30% achieve remission and mortality is up to 10%.[48] A full recovery can be expected for people who seek treatment and do not have more lesions at 12 and 24 months. However, 50% of children under 2 with disseminated Langerhans cell histiocytosis die of the disease. The prognosis rate decreases for patients who experience lung involvement. Whereas patients with skin and a solitary lymph node involvement generally have a good prognosis.[49] Although there is a general good prognosis for Langerhans cell histiocytosis, approximately 50% of patients with the disease are prone to various complications such as musculoskeletal disability, skin scarring and diabetes insipidus.[49]

Prevalence

editLCH usually affects children between 1 and 15 years old, with a peak incidence between 5 and 10 years of age. Among children under the age of 10, yearly incidence is thought to be 1 in 200,000;[50] and in adults even rarer, in about 1 in 560,000.[51] It has been reported in elderly but is vanishingly rare.[52] It is most prevalent in Caucasians, and affects males twice as often as females.[53] In other populations too the prevalence in males is slightly more than in females.[54]

LCH is usually a sporadic and non-hereditary condition but familial clustering has been noted in limited number of cases. Hashimoto-Pritzker disease is a congenital self-healing variant of Hand-Schüller-Christian disease.[55]

Nomenclature

editLangerhans cell histiocytosis is occasionally misspelled as "Langerhan" or "Langerhan's" cell histiocytosis, even in authoritative textbooks. The name, however, originates back to its discoverer, Paul Langerhans.[56]

References

edit- ^ a b "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "UpToDate". UpToDate. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Feldman, Andrew L; Berthold, Frank; Arceci, Robert J; Abramowsky, Carlos; Shehata, Bahig M; Mann, Karen P; Lauer, Stephen J; Pritchard, Jon; Raffeld, Mark; Jaffe, Elaine S (2005). "Clonal relationship between precursor T-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma and Langerhans-cell histiocytosis". The Lancet Oncology. 6 (6). Elsevier BV: 435–437. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(05)70211-4. ISSN 1470-2045. PMID 15925822.

- ^ The Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society (1987). "Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society". Lancet. 1 (8526): 208–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90016-X. PMID 2880029. S2CID 54351490.(subscription required)

- ^ Makras P, Papadogias D, Kontogeorgos G, Piaditis G, Kaltsas G (2005). "Spontaneous gonadotrophin deficiency recovery in an adult patient with Langerhans cell Histiocytosis (LCH)". Pituitary. 8 (2): 169–74. doi:10.1007/s11102-005-4537-z. PMID 16379033. S2CID 7878051.

- ^ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (2010). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (7th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-6795-9.

- ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Robbins, Stanley L. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 701–. ISBN 978-0-8089-2302-2.

- ^ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul; Aster, Jon (2015). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. p. 622. ISBN 978-1-4557-2613-4.

- ^ Afsar, Fatma Sule; Ergin, Malik; Ozek, Gulcihan; Vergin, Canan; Karakuzu, Ali; Seremet, Sila (2017). "Histiocitose de Células de Langerhans Autolimitada e de Início Tardio: Relato de Uma Entidade Raríssima". Revista Paulista de Pediatria. 35 (1): 115–119. doi:10.1590/1984-0462/;2017;35;1;00015. ISSN 0103-0582. PMC 5417814. PMID 28977321.

- ^ Ladisch, Stephan (2011). "Histiocytosis Syndromes of Childhood". In Kliegman, Robert M.; Stanton, Bonita F.; St. Geme, Joseph; Schor, Nina; Behrman, Richard E. (eds.). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (19th ed.). Saunders. pp. 1773–7. ISBN 978-1-4377-0755-7.

- ^ Pushpalatha, G; Aruna, DR; Galgali, Sushma (2011). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis". Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology. 15 (3). Medknow: 276–279. doi:10.4103/0972-124x.85675. ISSN 0972-124X. PMC 3200027. PMID 22028518.

- ^ Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis at eMedicine

- ^ Juvet, Stephan (2010). "Rare lung diseases III: Pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis". Canadian Respiratory Journal. 17 (3): e55–e62. doi:10.1155/2010/216240. PMC 2900147. PMID 20617216.

- ^ Tazi, A (2006). "Adult pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis". European Respiratory Journal. 27 (6): 1272–1285. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00024004. PMID 16772390. S2CID 5626880.

- ^ Juvet, Stephen C; Hwang, David; Downey, Gregory P (2010). "Rare lung diseases III: pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis". Canadian Respiratory Journal. 17 (3): e55–62. doi:10.1155/2010/216240. PMC 2900147. PMID 20617216.

- ^ Stull, MA; Kransdorf, MJ; Devaney, KO (July 1992). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone". Radiographics. 12 (4): 801–23. doi:10.1148/radiographics.12.4.1636041. PMID 1636041.

- ^ "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis — Patient UK". Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Kaltsas, GA; Powles, TB; Evanson, J; Plowman, PN; Drinkwater, JE; Jenkins, PJ; Monson, JP; Besser, GM; Grossman, AB (April 2000). "Hypothalamo-pituitary abnormalities in adult patients with langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical, endocrinological, and radiological features and response to treatment". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 85 (4): 1370–6. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.4.6501. PMID 10770168.

- ^ Grois, N; Pötschger, U; Prosch, H; Minkov, M; Arico, M; Braier, J; Henter, JI; Janka-Schaub, G; Ladisch, S; Ritter, J; Steiner, M; Unger, E; Gadner, H; DALHX- and LCH I and II Study, Committee (February 2006). "Risk factors for diabetes insipidus in langerhans cell histiocytosis". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 46 (2): 228–33. doi:10.1002/pbc.20425. PMID 16047354. S2CID 11069765.

- ^ Marchand, Isis; Barkaoui, Mohamed Aziz; Garel, Catherine; Polak, Michel; Donadieu, Jean (2011-09-01). "Central Diabetes Insipidus as the Inaugural Manifestation of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Natural History and Medical Evaluation of 26 Children and Adolescents". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 96 (9): E1352–E1360. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0513. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 21752883.

- ^ Broadbent, V; Dunger, DB; Yeomans, E; Kendall, B (1993). "Anterior pituitary function and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging in patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis and diabetes insipidus". Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 21 (9): 649–54. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950210908. PMID 8412998.

- ^ Sholl, LM; Hornick, JL; Pinkus, JL; Pinkus, GS; Padera, RF (June 2007). "Immunohistochemical analysis of langerin in langerhans cell histiocytosis and pulmonary inflammatory and infectious diseases". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 31 (6): 947–52. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000249443.82971.bb. PMID 17527085. S2CID 19702745.

- ^ Cisternino A, Asa'ad F, Fusco N, Ferrero S, Rasperini G (Oct 2015). "Role of multidisciplinary approach in a case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis with initial periodontal manifestations". Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 8 (10): 13539–45. PMC 4680515. PMID 26722570.

- ^ Broadbent, V.; Davies, E.G.; Heaf, D.; Pincott, J.R.; Pritchard, J.; Levinsky, R.J.; Atherton, D.J.; Tucker, S. (1984). "Spontaneous remission of multi-system histiocytosis X". Lancet. 1 (8371): 253–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90127-2. PMID 6142997. S2CID 46217705.

- ^ Filippi, Paola; De Badulli, Carla; Cuccia, Mariaclara; Silvestri, Annalisa; De Dametto, Ennia; Pasi, Annamaria; Garaventa, Alberto; Prever, Adalberto Brach; del Todesco, Alessandra; Trizzino, Antonino; Danesino, Cesare; Martinetti, Miryam; Arico, Maurizio (2006). "Specific polymorphisms of cytokine genes are associated with different risks to develop single-system or multi-system childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis". British Journal of Haematology. 132 (6): 784–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05922.x. PMID 16487180.

- ^ Steen, A.E.; Steen, K.H.; Bauer, R.; Bieber, T. (1 July 2001). "Successful treatment of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis with low-dose methotrexate". British Journal of Dermatology. 145 (1): 137–140. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04298.x. PMID 11453923. S2CID 34121488.

- ^ Allen CE, Flores R, Rauch R, Dauser R, Murray JC, Puccetti D, Hsu DA, Sondel P, Hetherington M, Goldman S, McClain KL (2010). "Neurodegenerative central nervous system Langerhans cell histiocytosis and coincident hydrocephalus treated with vincristine/cytosine arabinoside". Pediatr Blood Cancer. 54 (3): 416–23. doi:10.1002/pbc.22326. PMC 3444163. PMID 19908293.

- ^ Minkov, M.; Grois, N.; Broadbent, V.; Ceci, A.; Jakobson, A.; Ladisch, S. (1 November 1999). "Cyclosporine A therapy for multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis". Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 33 (5): 482–485. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199911)33:5<482::AID-MPO8>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 10531573.

- ^ Willman, Cheryl L.; Busque, Lambert; Griffith, Barbara B.; Favara, Blaise E.; McClain, Kenneth L.; Duncan, Marilyn H.; Gilliland, D. Gary (21 July 1994). "Langerhans'-Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X) -- A Clonal Proliferative Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 331 (3): 154–160. doi:10.1056/NEJM199407213310303. PMID 8008029.

- ^ Degar, Barbara A.; Rollins, Barrett J. (September 2, 2009). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis: malignancy or inflammatory disorder doing a great job of imitating one?". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2 (9–10). The Company of Biologists: 436–439. doi:10.1242/dmm.004010. ISSN 1754-8411. PMC 2737054. PMID 19726802.

- ^ Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, Calicchio ML, Kuo FC, Ligon AH, Stevenson KE, Kehoe SM, Garraway LA, Hahn WC, Meyerson M, Fleming MD, Rollins BJ (2010). "Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis". Blood. 116 (11): 1919–23. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083. PMC 3173987. PMID 20519626.

- ^ Satoh T, Smith A, Sarde A, Lu HC, Mian S, Mian S, Trouillet C, Mufti G, Emile JF, Fraternali F, Donadieu J, Geissmann F (2012). "B-RAF mutant alleles associated with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a granulomatous pediatric disease". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e33891. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...733891S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033891. PMC 3323620. PMID 22506009.

- ^ Peters, Tricia L.; Tsz-Kwong Chris Man; Price, Jeremy; George, Renelle; Phaik Har Lim; Kenneth Matthew Heym; Merad, Miriam; McClain, Kenneth L.; Allen, Carl E. (10 December 2011). "1372 Frequent BRAF V600E Mutations Are Identified in CD207+ Cells in LCH Lesions, but BRAF Status does not Correlate with Clinical Presentation of Patients or Transcriptional Profiles of CD207+ Cells".

Oral and Poster Abstracts presented at 53rd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Padmanaban, Kamalakannan; Kamalakaran, Arunkumar; Raghavan, Priyadharshini; Palani, Triveni; Rajiah, Davidson (August 21, 2022). "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Mandible". Cureus. 14 (8). Cureus, Inc.: e28222. doi:10.7759/cureus.28222. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 9486456. PMID 36158441.

- ^ Tillotson, Cara V.; Anjum, Fatima; Patel, Bhupendra C. (July 17, 2023). "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis". StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28613635. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Monsereenusorn, Chalinee; Rodriguez-Galindo, Carlos (October 2015). "Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 29 (5): 853–873. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.005. PMID 26461147.

- ^ Kaltsas, G. A.; Powles, T. B.; Evanson, J.; Plowman, P. N.; Drinkwater, J. E.; Jenkins, P. J.; Monson, J. P.; Besser, G. M.; Grossman, A. B. (2000). "Hypothalamo-Pituitary Abnormalities in Adult Patients with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Clinical, Endocrinological, and Radiological Features and Response to Treatment". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 85 (4). The Endocrine Society: 1370–1376. doi:10.1210/jcem.85.4.6501. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 10770168.

- ^ a b Wilson, AJ; Maddox, PH; Jenkins, D (January 1991). "CD1a and S100 antigen expression in skin Langerhans cells in patients with breast cancer". The Journal of Pathology. 163 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1002/path.1711630106. PMID 2002421. S2CID 70911084.

- ^ Coppola, D; Fu, L; Nicosia, SV; Kounelis, S; Jones, M (May 1998). "Prognostic significance of p53, bcl-2, vimentin, and S100 protein-positive Langerhans cells in endometrial carcinoma". Human Pathology. 29 (5): 455–62. doi:10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90060-0. PMID 9596268.

- ^ McLelland, J; Chu, AC (October 1988). "Comparison of peanut agglutinin and S100 stains in the paraffin tissue diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis". The British Journal of Dermatology. 119 (4): 513–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03255.x. PMID 2461216. S2CID 32685876.

- ^ Ye, F; Huang, SW; Dong, HJ (November 1990). "Histiocytosis X. S-100 protein, peanut agglutinin, and transmission electron microscopy study". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 94 (5): 627–31. doi:10.1093/ajcp/94.5.627. PMID 2239828.

- ^ Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Moore K, Kleijmeer M, Liu Y, Duvert-Frances V, Vincent C, Schmitt D, Davoust J, Caux C, Lebecque S, Saeland S (2000). "Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules". Immunity. 12 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80160-0. PMID 10661407.

- ^ Lau, SK; Chu, PG; Weiss, LM (April 2008). "Immunohistochemical expression of Langerin in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disorders". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 32 (4): 615–9. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815b212b. PMID 18277880. S2CID 40092500.

- ^ Haupt, Riccardo; Minkov, Milen; Astigarraga, Itziar; Schäfer, Eva; Nanduri, Vasanta; Jubran, Rima; Egeler, R. Maarten; Janka, Gritta; Micic, Dragan; Rodriguez-Galindo, Carlos; Van Gool, Stefaan; Visser, Johannes; Weitzman, Sheila; Donadieu, Jean (February 2013). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): Guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 60 (2): 175–184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367. PMC 4557042. PMID 23109216.

- ^ Girschikofsky, Michael; Arico, Maurizio; Castillo, Diego; Chu, Anthony; Doberauer, Claus; Fichter, Joachim; Haroche, Julien; Kaltsas, Gregory A; Makras, Polyzois; Marzano, Angelo V; de Menthon, Mathilde; Micke, Oliver; Passoni, Emanuela; Seegenschmiedt, Heinrich M; Tazi, Abdellatif; McClain, Kenneth L (2013). "Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 8 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-72. PMC 3667012. PMID 23672541.

- ^ "Langerhans cell histiocytosis — Histiocyte Society Evaluation and Treatment Guidelines". April 2009. Archived from the original on 2018-01-21. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board (2002). "Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version". Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Treatment (PDQ®). National Cancer Institute (US). PMID 26389240. and 1

- ^ Komp D, El Mahdi A, Starling K, Easley J, Vietti T, Berry D, George S (1980). "Quality of survival in Histiocytosis X: a Southwest Oncology Group study". Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 8 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950080106. PMID 6969347.

- ^ a b Tillotson CV, Anjum F, Patel BC. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430885/

- ^ "MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Histiocytosis". Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ "Histiocytosis Association of Canada". Archived from the original on 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ Gerlach, Beatrice; Stein, Annette; Fischer, Rainer; Wozel, Gottfried; Dittert, Dag-Daniel; Richter, Gerhard (1998). "Langerhanszell-Histiozytose im Alter" [Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the elderly]. Der Hautarzt (in German). 49 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1007/s001050050696. PMID 9522189. S2CID 20706403.

- ^ Sellari-Franceschini, S.; Forli, F.; Pierini, S.; Favre, C.; Berrettini, S.; Macchia, P.A. (1999). "Langerhans' cells histiocytosis: a case report". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 48 (1): 83–7. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00013-0. PMID 10365975.

- ^ Aricò, M.; Girschikofsky, M.; Généreau, T.; Klersy, C.; McClain, K.; Grois, N.; Emile, J.-F.; Lukina, E.; De Juli, E.; Danesino, C. (2003). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: Report from the International Registry of the Histiocyte Society". European Journal of Cancer. 39 (16): 2341–8. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00672-5. PMID 14556926.

- ^ Kapur, Payal; Erickson, Christof; Rakheja, Dinesh; Carder, K. Robin; Hoang, Mai P. (2007). "Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): Ten-year experience at Dallas Children's Medical Center". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 56 (2): 290–4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.001. PMID 17224372.

- ^ Jolles, S. (April 2002). "Paul Langerhans". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 55 (4): 243. doi:10.1136/jcp.55.4.243. PMC 1769627. PMID 11919207.