The oldest evidence of ancient wine production has been found in Georgia from c. 6000 BC (the earliest known traces of grape wine),[1][2][3][4] Iran from c. 5000 BC,[5] Greece from c. 4500 BC,[6][7] Armenia from c. 4100 BC (large-scale production),[8][9][10][11][12][13] and Sicily from c. 4000 BC.[14] The earliest evidence of fermented alcoholic beverage of rice, honey and fruit, sometimes compared to wine, is claimed in China (c. 7000 BC).[15][16][17]

The altered consciousness produced by wine has been considered religious since its origin. The ancient Greeks worshiped Dionysus or Bacchus and the Ancient Romans carried on his cult.[18][19] Consumption of ritual wine, probably a certain type of sweet wine originally, was part of Jewish practice since Biblical times and, as part of the eucharist commemorating Jesus's Last Supper, became even more essential to the Christian Church.[20] Although Islam nominally forbade the production or consumption of wine, during its Golden Age, alchemists such as Geber pioneered wine's distillation for medicinal and industrial purposes such as the production of perfume.[21]

Wine production and consumption increased, burgeoning from the 15th century onwards as part of European expansion. Despite the devastating 1887 phylloxera louse infestation, modern science and technology adapted and industrial wine production and widespread consumption now occur throughout the world.

Prehistory

editVine domestication

editThe origins of wine predate written records, and modern archaeology is still uncertain about the details of the first cultivation of wild grapevines. It has been hypothesized that early humans climbed trees to pick berries, liked their sugary flavor, and then began collecting them. After a few days with fermentation setting in, juice at the bottom of any container would begin producing low-alcohol wine. According to this theory, things changed around 10,000–8000 BC with the transition from a nomadic to a sedentary style of living, which led to agriculture and wine domestication.[22]

The fermenting of strains of Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris (the ancestor of the modern wine grape, V. vinifera) would have become easier following the development of pottery during the later Neolithic period, c. 11,000 BC. The earliest discovered evidence, however, dates from several millennia later.[citation needed]

Wine fermentation

editThe earliest archaeological evidence of wine fermentation found has been at sites in Georgia (c. 6000 BC),[2][23][3][4] Hajj Firuz, West Azerbaijan province of Iran (c. 5000 BC),[5][24] Greece (c. 4500 BC), and Sicily (c. 4000 BC).[14] The earliest evidence of steady production of wine has been found in Armenia (c. 4100 BC)[25][26][27][28] while the earliest evidence of a grape and rice mixed based fermented drink was found in ancient China (c. 7000 BC),.[15][16][17][29][30] The Iranian jars contained a form of retsina, using turpentine pine resin to more effectively seal and preserve the wine and is the earliest firm evidence of wine production to date.[31][25][26][27][28] Production spread to other sites in Greater Iran and Greek Macedonia by c. 4500 BC. The Greek site is notable for the recovery at the site of the remnants of crushed grapes.[32]

The oldest-known winery was discovered in the "Areni-1" cave in Vayots Dzor, Armenia. Dated to c. 4100 BC, the site contained a wine press, fermentation vats, jars, and cups.[33][34][35][36] Archaeologists also found V. vinifera seeds and vines. Commenting on the importance of the find, McGovern said, "The fact that winemaking was already so well developed in 4000 BC suggests that the technology probably goes back much earlier."[36][37]

The seeds were from Vitis vinifera, a grape still used to make wine.[28] The cave remains date to about 4000 BC. This is 900 years before the earliest comparable wine remains, found in Egyptian tombs.[38][39]

The fame of Persian wine has been well known in ancient times. The carvings on the Audience Hall, known as Apadana Palace, in Persepolis, demonstrate soldiers of subjected nations by the Persian Empire bringing gifts to the Persian king.

Domesticated grapes were abundant in the Near East from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, starting in 3200 BC. There is also increasingly abundant evidence for winemaking in Sumer and Egypt in the 3rd millennium BC.[40]

Legends of discovery

editThere are many etiological myths told about the first cultivation of the grapevine and fermentation of wine.

The Biblical Book of Genesis first mentions the production of wine by Noah following the Great Flood.

Greek mythology placed the childhood of Dionysus and his discovery of viticulture at Mount Nysa but had him teach the practice to the peoples of central Anatolia. Because of this, he was rewarded to become a god of wine.

In Persian legend, King Jamshid banished a lady of his harem, causing her to become despondent and contemplate suicide. Going to the king's warehouse, the woman sought out a jar marked "poison" containing the remnants of the grapes that had spoiled and were now deemed undrinkable. After drinking the fermented wine, she found her spirits lifted. She took her discovery to the king, who became so enamored of his new drink that he not only accepted the woman back but also decreed that all grapes grown in Persepolis would be devoted to winemaking.[41]

Antiquity

editAncient China

editThis article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (December 2023) |

Archaeologists have discovered production from native "mountain grapes" like V. thunbergii[42] and V. filifolia[43] during the 1st millennium BC.[44] Production of beer had largely disappeared by the time of the Han dynasty, in favor of stronger drinks fermented from millet, rice, and other grains. Although these huangjiu have frequently been translated as "wine", they are typically 20% ABV and considered quite distinct from grape wine (葡萄酒) within China.

During the 2nd century BC, Zhang Qian's exploration of the Western Regions (modern Xinjiang) reached the Hellenistic successor states of Alexander's empire: Dayuan, Bactria, and the Indo-Greek Kingdom. These had brought viticulture into Central Asia and trade permitted the first wine produced from V. vinifera grapes to be introduced to China.[43][45][46]

Wine was imported again when trade with the west was restored under the Tang dynasty, but it remained mostly imperial fare and it was not until the Song that its consumption spread among the gentry.[46] Marco Polo's 14th-century account noted the continuing preference for rice wines continuing in Yuan China.[46]

Ancient Egypt

editWine played an important role in ancient Egyptian ceremonial life. A thriving royal winemaking industry was established in the Nile Delta following the introduction of grape cultivation from the Levant to Egypt c. 3000 BC. The industry was most likely the result of trade between Egypt and Canaan during the early Bronze Age, commencing from at least the 27th-century BC Third Dynasty, the beginning of the Old Kingdom period. Winemaking scenes on tomb walls, and the offering lists that accompanied them, included wine that was definitely produced in the delta vineyards. By the end of the Old Kingdom, five distinct wines, probably all produced in the Delta, constituted a canonical set of provisions for the afterlife.

Wine in ancient Egypt was predominantly red. Due to its resemblance to blood, much superstition surrounded wine-drinking in Egyptian culture. Shedeh, the most precious drink in ancient Egypt, is now known to have been a red wine and not fermented from pomegranates as previously thought.[47] Plutarch's Moralia relates that, prior to Psammetichus I, the pharaohs did not drink wine nor offer it to the gods "thinking it to be the blood of those who had once battled against the gods and from whom, when they had fallen and had become commingled with the earth, they believed vines to have sprung". This was considered to be the reason why drunkenness "drives men out of their senses and crazes them, inasmuch as they are then filled with the blood of their forebears".[48]

Residue from five clay amphoras in Tutankhamun's tomb, however, have been shown to be that of white wine, so it was at least available to the Egyptians through trade if not produced domestically.[49]

Ancient Levant

editIn ancient times, the Levant region has played a vital role in the domain of winemaking. Archaeological findings, including charred grape seeds and occasionally intact berries or raisins, have been unearthed in numerous prehistoric and historic sites across Southwest Asia. Having deep historical roots dating back to at least the Bronze Age, winemaking in the Levant retained its importance as a significant regional industry until the decline of Byzantine rule in the 7th century CE. This prolonged history of winemaking significantly enriched the cultural and economic tapestry of ancient societies in the region, giving rise to numerous legends and beliefs intertwined with its consumption in the Mediterranean and Near East.[50][51]

The ancient Phoenicians stood among the early civilizations to acknowledge the significance of cultivating and trading wine.[1] Positioned along the eastern Mediterranean coast, the Phoenicians leveraged their location for far-reaching trade networks across the ancient world. The Israelite prophet Hosea (780–725 BC) is said to have urged his followers to return to Yahweh so that "they will blossom as the vine, [and] their fragrance will be like the wine of Lebanon".[8] The Phoenician use of amphoras for transporting wine was widely adopted and Phoenician-distributed grape varieties were important in the development of the wine industries of Rome and Greece. The Phoenicians also established colonies along the Mediterranean coasts, from modern-day Tunisia to Spain, where they introduced viticulture practices and grape cultivation. One such colony was Carthage, a city that later developed into a maritime empire. The only Carthaginian recipe to survive the Punic Wars was one by Mago for passum, a raisin wine that later became popular in Rome as well.

Wine held a significant and favored role within ancient Israelite cuisine, serving not only as a dietary staple but also as a crucial element of Israelite cultural and religious practices. In ancient Israel, wine found its place in both everyday use and ceremonial rituals such as sacrificial libations.[52] These traditions became an integral part of Jewish customs and celebrations, upholding the enduring importance of wine within Judaism to this very day. The abundancy of archeological remnants of facilities dedicated to the production of wine (at ancient Gibeon, for example), coupled with detailed depictions of vineyard establishment and grape varieties within the Hebrew Bible,[52][53] underscore the prominence of wine as the primary alcoholic choice for the ancient Israelites. Within the Hebrew language, a multitude of terms emerged relating to vines and the various stages of winemaking.[54] Winemaking also included the incorporation of spices, honey, herbs, and other ingredients. Following the fermentation process, the wine was meticulously stored in amphorae, often lined with protective resin coatings to ensure preservation. Jewish winemaking evolved during the Hellenistic period, with dried grapes producing sweeter, higher alcohol content wine that required dilution with water for consumption.[53]

During Late Antiquity, when the Levant was under Byzantine control, the region established itself as a renowned center for winemaking. Ashkelon and Gaza, two ancient port cities in modern-day Israel and Gaza Strip, rose to prominence as important trade centers, facilitating extensive wine exports throughout the Byzantine Empire. The writings of 4th-century CE priest Jerome vividly depicted the Holy Land's landscape adorned with sprawling vineyards. The wines of this region, as described by the 6th-century CE poet Corippus, stood out for their attributes of being white, light, and sweet.[55]

In the Arabian Peninsula, wine was traded by Aramaic merchants, as the climate was not well-suited to the growing of vines. Many other types of fermented drinks, however, were produced in the 5th and 6th centuries, including date and honey wines.

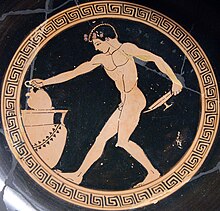

Ancient Greece

editMuch of modern wine culture derives from the practices of the ancient Greeks. The vine preceded both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures.[18][32] Many of the grapes grown in modern Greece are grown there exclusively and are similar or identical to the varieties grown in ancient times. Indeed, the most popular modern Greek wine, a strongly aromatic white called retsina, is thought to be a carryover from the ancient practice of lining the wine jugs with tree resin, imparting a distinct flavor to the drink.

The "Feast of the Wine" (Me-tu-wo Ne-wo) was a festival in Mycenaean Greece celebrating the "Month of the New Wine".[56][57][58] Several ancient sources, such as the Roman Pliny the Elder, describe the ancient Greek method of using partly dehydrated gypsum before fermentation and some type of lime after, in order to reduce the acidity of the wine. The Greek Theophrastus provides the oldest known description of this aspect of Greek winemaking.[59][60]

In Homeric mythology, wine is usually served in "mixing bowls" rather than consumed in an undiluted state. Dionysus, the Greek god of revelry and wine—frequently referred to in the works of Homer and Aesop—was sometimes given the epithet Acratophorus, "giver of unmixed wine".[61][62] Homer frequently refers to the "wine-dark sea" (οἶνωψ πόντος, oīnōps póntos): while having several words for the color blue despite modern claims, the Greeks would simply refer to red wine's color as the sea appeared darker than their perspective of a 'blue' shade.

The earliest reference to a named wine is from the 7th-century BC lyrical poet Alcman, who praises Dénthis, a wine from the western foothills of Mount Taygetus in Messenia, as anthosmías ("flowery-scented"). Chian was credited as the first red wine, although it was known to the Greeks as "black wine".[63][64] Coan was mixed with sea water and famously salty;[65] Pramnian or Lesbian wine was a famous export as well. Aristotle mentions Lemnian wine, which was probably the same as the modern-day Lemnió varietal, a red wine with a bouquet of oregano and thyme. If so, this makes Lemnió the oldest known varietal still in cultivation.

For Greece, alcohol such as wine had not fully developed into the rich 'cash crop' that it would eventually become toward the peak of its reign. However, as the emphasis of viticulture increased with economic demand so did the consumption of alcohol during the years to come. The Greeks embraced the production aspect as a way to expand and create economic growth throughout the region. Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the Mediterranean, as amphoras with Greek styling and art have been found throughout the area. The Greeks may have even been involved in the first appearance of wine in ancient Egypt.[66] They introduced the V. vinifera vine to[67] and made wine in their numerous colonies in modern-day Italy,[68] Sicily,[69] southern France,[70] and Spain.[67]

Ancient Persia

editHerodotus, writing about the culture of the ancient Persians (in particular, those of Pontus) writes that they were "very fond" of wine and drank it in large quantities.[71]

Ancient Thrace

editThe works of Homer, Herodotus and other historians of Ancient Greece refer to the ancient Thracians' love for winemaking and consumption,[72] as early as 6000 years ago.[73] the Thracians are considered the first to worship the god of wine called Dionysus in Greek or Zagreus in Thracian. Later this cult reached Ancient Greece.[74][75] Some consider Thrace (modern day Bulgaria) as the motherland of wine culture.[76]

Roman Empire

editThe Roman Empire had an immense impact on the development of viticulture and oenology. Wine was an integral part of the Roman diet and winemaking became a precise business. Virtually all of the major wine-producing regions of Western Europe today were established during the Roman Imperial era. During the Roman Empire, social norms began to shift as the production of alcohol increased. Further evidence suggests that widespread drunkenness and true alcoholism among the Romans began in the first century BC and reached its height in the first century AD.[77] Viniculture expanded so much that by AD c. 92 the emperor Domitian was forced to pass the first wine laws on record, banning the planting of any new vineyards in Italy and uprooting half of the vineyards in the provinces in order to increase the production of the necessary but less profitable grain. (The measure was widely ignored but remained on the books until its 280 repeal by Probus.[78])

Winemaking technology improved considerably during the time of the Roman Empire, though technologies from the Bronze Age continued to be used alongside newer innovations.[79][20] Vitruvius noted how wine storage rooms were specially built facing north, "since that quarter is never subject to change but is always constant and unshifting",[80] and special smokehouses (fumaria) were developed to speed or mimic aging. Many grape varieties and cultivation techniques were developed. Barrels (invented by the Gauls) and glass bottles (invented by the Syrians) began to compete with terracotta amphoras for storing and shipping wine. The Romans also created a precursor to today's appellation systems, as certain regions gained reputations for their fine wines. The most famous was the white Falernian from the Latian–Campanian border, principally because of its high (~15%) alcohol content. The Romans recognized three appellations: Caucinian Falernian from the highest slopes, Faustian Falernian from the center (named for its one-time owner Faustus Cornelius Sulla, son of the dictator), and generic Falernian from the lower slopes and plain. The esteemed vintages grew in value as they aged, and each region produced different varieties as well: dry, sweet, and light. Other famous wines were the sweet Alban from the Alban Hills and the Caecuban beloved by Horace and extirpated by Nero. Pliny cautioned that such 'first-growth' wines not be smoked in a fumarium like lesser vintages.[81] Pliny and others also named Vinum Hadrianum as one of the most rated wines, along with Praetutian from Ancona on the Adriatic, Mamertine from Messina in Sicily, Rhaetic from Verona, and a few others.[82]

Wine, perhaps mixed with herbs and minerals, was assumed to serve medicinal purposes. During Roman times, the upper classes might dissolve pearls in wine for better health. Cleopatra created her own legend by promising Antony she would "drink the value of a province" in one cup of wine, after which she drank an expensive pearl with a cup of the beverage.[60] Pliny relates that, after the ascension of Augustus, Setinum became the imperial wine because it did not cause him indigestion.[83] When the Western Roman Empire fell during the 5th century, Europe entered a period of invasions and social turmoil, with the Roman Catholic Church as the only stable social structure. Through the Church, grape growing and winemaking technology, essential for the Mass, were preserved.[84]

Over the course of the later Empire, wine production gradually shifted to the east as Roman infrastructure and influence in the western regions gradually diminished. Production in Asia Minor, the Aegean and the Near East flourished through Late Antiquity and the Byzantine era.[20]

The oldest surviving urn of wine in liquid state was found in 2019 in a Roman mausoleum in Carmona, southern Spain, and is about 2000 years old.[85] The second oldest surviving bottle still containing liquid wine is the Speyer wine bottle, that belonged to a Roman nobleman and it is dated at 325 or 350 AD.[86][87]

Medieval period

editMedieval Middle East

editThe advent of Islam and subsequent Muslim conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries brought many territories under Muslim control. Alcoholic drinks were prohibited by law, but the production of alcohol, wine in particular, seems to have thrived.[88] Wine was a subject for many poets, even under Islamic rule, and many khalifas used to drink alcoholic beverages during their social and private meetings. Jews in Egypt leased vineyards from the Fatimid and Mamluk governments, produced wine for sacramental and medicinal use, and traded wine throughout the Eastern Mediterranean.

Christian monasteries in the Levant and Iraq often cultivated grapevines; they then distributed their vintages in taverns located on monastery grounds. Zoroastrians in Persia and Central Asia also engaged in the production of wine. Though not much is known about their wine trade, they did become known for their taverns. Wine in general found an industrial use in the medieval Middle East as feedstock after advances in distillation by Muslim alchemists allowed for the production of relatively pure ethanol, which was used in the perfume industry. Wine was also for the first time distilled into brandy during this period.

In the Levant, the Muslim conquest of the Levant suppressed winemaking after centuries of regional prominence, and the 13th-century Mamluk conquest resulted in its complete prohibition.[50]

Medieval Europe

editIt has been one of history's cruel ironies that the [Christian medieval] blood libel—accusations against Jews using the blood of murdered gentile children for the making of wine and matzot—became the false pretext for numerous pogroms. And due to the danger, those who live in a place where blood libels occur are halachically exempted from using [kosher] red wine, lest it be seized as "evidence" against them.

— Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It, Project Genesis[89]

In the Middle Ages, wine was the common drink of all social classes in the south of Europe, where grapes were cultivated. In the north and east, where few if any grapes were grown, beer and ale were the usual beverages of both commoners and nobility. Wine was exported to the northern regions, but because of its relatively high expense was seldom consumed by the lower classes. Since wine was necessary, however, for the celebration of the Catholic Mass, assuring a supply was crucial. The Benedictine monks became one of the largest producers of wine in France and Germany, followed closely by the Cistercians. Other orders, such as the Carthusians, the Templars, and the Carmelites, are also notable both historically and in modern times as wine producers. The Benedictines owned vineyards in Champagne (Dom Perignon was a Benedictine monk), Burgundy, and Bordeaux in France, and in the Rheingau and Franconia in Germany. In 1435 Count John IV of Katzenelnbogen, a wealthy member of the high nobility of the Holy Roman Empire from near Frankfurt, was the first to plant Riesling, the most important German grape. The nearby winemaking monks made it into an industry, producing enough wine to ship all over Europe for secular use. Portugal, a country with one of the oldest wine traditions, developed the first wine appellation system in the world.

A housewife of the merchant class or a servant in a noble household would have served wine at every meal, and had a selection of reds and whites alike. Home recipes for meads from this period are still in existence, along with recipes for spicing and masking flavors in wines, including the simple act of adding a small amount of honey. As wines were kept in barrels, they were not extensively aged, and thus drunk quite young. To offset the effects of heavy alcohol-consumption, wine was frequently watered down at a ratio of four or five parts water to one of wine.

One medieval application of wine was the use of snake-stones (banded agate resembling the figural rings on a snake) dissolved in wine as a remedy for snake bites, which shows an early understanding of the effects of alcohol on the central nervous system in such situations.[60]

Jofroi of Waterford, a 13th-century Dominican, wrote a catalogue of all the known wines and ales of Europe, describing them with great relish and recommending them to academics and counsellors. Rashi, a medieval French rabbi called the "father" of all subsequent commentaries on the Talmud and the Tanakh,[90] earned his living as a vintner.

Medieval names for types of wine included "pimentum"[91] and "malmsey".

Modern era

editSpread and development in the Americas

editFollowing the voyages of Columbus, grape culture and wine making were transported from the Old World to the New. European grape varieties were first brought to what is now Mexico by the first Spanish conquistadors to provide the necessities of the Catholic Holy Eucharist. Planted at Spanish missions, one variety came to be known as the Mission grape and is still planted today in small amounts. Spanish missionaries also took viticulture to Chile and Argentina in the mid-16th century and to Baja California in the 18th.[92] Succeeding waves of immigrants, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, imported French, Italian and German V. vinifera grapes, although wine from those native to the Americas (whose flavors can be distinctly different) is also produced. Mexico became the most important wine producer starting in the 16th century, to the extent that its output began to affect Spanish commercial production. In this competitive climate, the Spanish king sent an executive order to halt Mexico's production of wines and the planting of vineyards.

During the devastating phylloxera blight in late 19th-century Europe, it was found that Native American vines were immune to the pest. French-American hybrid grapes were developed and saw some use in Europe, but more important was the practice of grafting European grapevines to American rootstocks to protect vineyards from the insect. The practice continues to this day wherever phylloxera is present.

The prime wine-growing regions of South America were established in the foothills of the Andes Mountains in Argentina and Chile. In California, the centre of viticulture shifted from the southern missions to the Central Valley and the northern counties of Sonoma, Napa, and Mendocino.[92] Today, wine in the Americas is still often associated with these regions, all of which produce a wide variety of wines, from inexpensive jug wines to high-quality varietals and proprietary blends. Most of the wine production in the Americas is based on Old World grape varieties, and wine-growing regions there have often "adopted" grapes that have become particularly closely identified with them. California's Zinfandel (from Croatia and Southern Italy), Argentina's Malbec, and Chile's Carmenère (both from France) are well-known examples.

Until the latter half of the 20th century, American wine was generally viewed as inferior to that of Europe. However, with the surprisingly favorable American showing at the Paris Wine tasting of 1976, New World wine began to garner respect in the land of wine's origins.

Developments in Europe

editIn the late 19th century, the phylloxera louse brought widespread destruction to grapevines, wine production, and those whose livelihoods depended on them; far-reaching repercussions included the loss of many indigenous varieties. Lessons learned from the infestation led to the positive transformation of Europe's wine industry. Bad vineyards were uprooted and their land turned to better uses. Some of France's best butter and cheese, for example, is now made from cows that graze on Charentais soil, which was previously covered with vines. Cuvées were also standardized, important in creating certain wines as they are known today; Champagne and Bordeaux finally achieved the grape mixes that now define them. In the Balkans, where phylloxera had had little impact, the local varieties survived. However, the uneven transition from Ottoman rule has meant only gradual transformation in many vineyards. It is only in recent times that local varieties have gained recognition beyond "mass-market" wines like retsina.

Australia, New Zealand and South Africa

editIn the context of wine, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and other countries without a wine tradition are considered New World producers. Wine production began in the Cape Province of what is now South Africa in the 1680s as a business for supplying ships. Australia's First Fleet (1788) brought cuttings of vines from South Africa, although initial plantings failed and the first successful vineyards were established in the early 19th century. Until quite late in the 20th century, the product of these countries was not well known outside their small export markets. For example, Australia exported mainly to the United Kingdom; New Zealand retained most of its wine for domestic consumption, and South Africa exported to the Kings of Europe. However, with the increase in mechanization and scientific advances in winemaking, these countries became known for high-quality wine. A notable exception to the foregoing is that the Cape Province was the largest exporter of wine to Europe in the 18th century.

East Asia

editIn East Asia, the first modern wine industry was Japanese wine, developed in 1874 after grapevines were brought back from Europe.[93] The earliest wine brewing companies in Japan include Suntory and Mercian.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "'World's oldest wine' found in 8,000-year-old jars in Georgia". BBC News. 13 November 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ a b Keys, David (28 December 2003). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b Cheslow, Daniella (8 June 2015). "Georgia's Giant Clay Pots Hold An 8,000-Year-Old Secret To Great Wine". NPR.

- ^ a b Spilling, Michael; Wong, Winnie (2008). Cultures of The World Georgia. Marshall Cavendish. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7614-3033-9.

- ^ a b Ellsworth, Amy (18 July 2012). "7,000 Year-old Wine Jar". University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Pagnoux, Clémence; Bouby, Laurent; Valamoti, Soultana Maria; Bonhomme, Vincent; Ivorra, Sarah; Gkatzogia, Eugenia; Karathanou, Angeliki; Kotsachristou, Dimitra; Kroll, Helmut; Terral, Jean-Frédéric (January 2021). "Local domestication or diffusion? Insights into viticulture in Greece from Neolithic to Archaic times, using geometric morphometric analyses of archaeological grape seeds". Journal of Archaeological Science. 125: 105263. Bibcode:2021JArSc.125j5263P. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105263.

- ^ Valamoti, Soultana Maria (January 2015). "Harvesting the 'wild'? Exploring the context of fruit and nut exploitation at Neolithic Dikili Tash, with special reference to wine". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 24 (1): 35–46. Bibcode:2015VegHA..24...35V. doi:10.1007/s00334-014-0487-6.

- ^ a b "6000-year-old winery found in Armenia – Ya Libnan". 11 January 2011.

- ^ "EIGHT OF THE WORLD'S OLDEST WINERIES".

- ^ Holding, Deirdre (September 2014). Armenia: with Nagorno Karabagh. The Globe Pequot Press Inc. p. 284. ISBN 9781841625553.

- ^ Johnson, Hugh (September 2014). Hugh Johnson's Pocket Wine Book 2019. Octopus Publishing Group. ISBN 9781784724825.

- ^ "Decanter". Decanter magazine. Vol. 36, no. 5–8. February 2011.

- ^ "Wine 4,100 B.C. – World's Oldest Winery Discovered". 27 August 2014.

- ^ a b Tondo, Lorenzo (30 August 2017). "Traces of 6,000-year-old wine discovered in Sicilian cave". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Li, Hua; Wang, Hua; Li, Huanmei; Goodman, Steve; Van Der Lee, Paul; Xu, Zhimin; Fortunato, Alessio; Yang, Ping (2018). "The worlds of wine: Old, new and ancient". Wine Economics and Policy. 7 (2): 178–182. doi:10.1016/j.wep.2018.10.002. hdl:10419/194558.

- ^ a b Cañete, Eduardo; Chen, Jaime; Martín, Cristian; Rubio, Bartolomé (2018). "Smart Winery: A Real-Time Monitoring System for Structural Health and Ullage in Fino Style Wine Casks" (PDF). Sensors. 18 (3): 803. Bibcode:2018Senso..18..803C. doi:10.3390/s18030803. PMC 5876521. PMID 29518928.

- ^ a b Hames, Gina (2010). Alcohol in World History. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781317548706.

- ^ a b The history of wine in ancient Greece Archived 12 July 2002 at the Wayback Machine at greekwinemakers.com

- ^ "UNESCO Pafos Archaeological Park".

- ^ a b c DODD, EMLYN K. (2020). ROMAN AND LATE ANTIQUE WINE PRODUCTION IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN : a comparative ... archaeological study at antiochia ad cragum. [Place of publication not identified]: ARCHAEOPRESS. ISBN 978-1-78969-403-1. OCLC 1139263254.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jancis Robinson; Julia Harding; Jose Vouillamoz (2013). Wine Grapes. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780062325518.

- ^ "Evidence of ancient wine found in Georgia a vintage quaffed some 6,000 years BC". Euronews. 21 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Berkowitz, Mark (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ a b "Earliest Known Winery Found in Armenian Cave". news.nationalgeographic.com. 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b Furer, David (12 January 2011). "Armenian find is 'world's oldest winery' – Decanter". Decanter. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Scientists discover 'oldest' winery in Armenian cave". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Hotz, Robert Lee. "Perhaps a Red, 4,100 B.C." The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ [1]. Prehistoric China – The Wonders That Were Jiahu The World’s Earliest Fermented Beverage. Professor Patrick McGovern the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. Retrieved on 3 January 2017.

- ^ Patrick E. McGovern; Anne P. Underhill; Hui Fang; Fengshi Luan; Gretchen R. Hall; Haiguang Yu; Chen-Shan Wang; Fengshu Cai; Zhijhun Zhao; Gary M. Feinman (2004). "Fermented Beverages of Pre- and Proto-Historic China" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 101 (51): 17593–9. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10117593M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. PMC 539767. PMID 15590771.

- ^ Maghradze, David; Samanishvili, Giorgi; Mekhuzla, Levan; Mdinaradze, Irma; Tevzadze, George; Aslanishvili, Andro; Chavchanidze, Paata; Lordkipanidze, David; Jalabadze, Mindia; Kvavadze, Eliso; Rusishvili, Nana; Nadiradze, Eldar; Archvadze, Gvantsa; McGovern, Patrick; This, Patrice; Bacilieri, Roberto; Failla, Osvaldo; Cola, Gabriele; Mariani, Luigi; Wales, Nathan; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Bouby, Laurent; Kazeli, Tina; Ujmajuridze, Levan; Batiuk, Stephen; Graham, Andrew; Megrelidze, Lika; Bagratia, Tamar; Davitashvili, Levan (2016). "Grape and wine culture in Georgia, the South Caucasus". Bio Web of Conferences. 7: 03027. doi:10.1051/bioconf/20160703027. hdl:2434/722349. S2CID 3892614.

- ^ a b Viegas, Jennifer (16 March 2007). "Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008.

- ^ "Earliest Known Winery Found in Armenian Cave". 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011.

- ^ David Keys (28 December 2003). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Mark Berkowitz (September–October 1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ a b "'Oldest known wine-making facility' found in Armenia". BBC News. BBC. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Thomas H. Maugh II (11 January 2011). "Ancient winery found in Armenia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "6,000-year-old winery found in Armenian cave (Wired UK)". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ "World's oldest winery discovered in Armenian cave". news.am. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Verango, Dan (29 May 2006). "White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb". USA Today. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ Pellechia, T. Wine: The 8,000-Year-Old Story of the Wine Trade, pp. XI–XII. Running Press (London), 2006. ISBN 1-56025-871-3.

- ^ Eijkhoff, P. Wine in China: its historical and contemporary developments (PDF).

- ^ a b Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a foreword by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Page 101.

- ^ Wine Production in China 3000 years ago Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Zhang Qian: Opening the Silk Road". monkeytree.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by H. M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0. Page 134–135.

- ^ Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Olga Jáuregui and Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol 33, Iss 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 98–101.

- ^ "Isis & Osiris". University of Chicago.

- ^ White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb. USA Today, 29 May 2006.

- ^ a b Sivan, Aviad; Rahimi, Oshrit; Lavi, Bar; Salmon-Divon, Mali; Weiss, Ehud; Drori, Elyashiv; Hübner, Sariel (2021). "Genomic evidence supports an independent history of Levantine and Eurasian grapevines". Plants, People, Planet. 3 (4): 414–427. doi:10.1002/ppp3.10197. ISSN 2572-2611. S2CID 235534373.

- ^ Harutyunyan, Mkrtich; Malfeito-Ferreira, Manuel (2022). "The Rise of Wine among Ancient Civilizations across the Mediterranean Basin". Heritage. 5 (2): 788–812. doi:10.3390/heritage5020043. hdl:10400.5/24195.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Nathan (2008). What Did the Ancient Israelites Eat?. pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Marks, Gil (2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. pp. 616–618.

- ^ Yeivin, Z (1966). Journal of the Israel Department of Antiquities. 3. Jerusalem: Israel Department of Antiquities: 52–62.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Decker, M. (2009). Tilling the Hateful Earth: Agricultural Production and Trade in the Late Antique East. Oxford University Press. pp. 136–139.

- ^ Mycenaean and Late Cycladic Religion and Religious Architecture, Dartmouth College

- ^ T.G. Palaima, The Last days of Pylos Polity Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Université de Liège

- ^ James C. Wright, The Mycenaean feast, American School of Classical Studies, 2004, on Google books

- ^ Caley, Earle (1956). Theophrastis on Stone. Ohio State University.Online version: Gypsum/lime in wine Archived 8 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Wine Drinking and Making in Antiquity: Historical References on the Role of Gemstones Many classic scientists such as Al Biruni, Theophrastus, Georg Agricola, Albertus Magnus as well as newer authors such as George Frederick Kunz describe the many talismanic, medicinal uses of minerals and wine combined.

- ^ Pausanias, viii. 39. § 4

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Acratophorus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 14.

- ^ Andrew Dalby (2002). Empire of Pleasures: Luxury and Indulgence in the Roman World. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-28073-0.

- ^ Aristoula Georgiadou; David H.J. Larmour (1998). Lucian's Science Fiction Novel 'True Histories': Interpretation and Commentary. BRILL. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-90-04-10970-4.

- ^ Andrew Dalby (2002). Empire of Pleasures: Luxury and Indulgence in the Roman World. Routledge. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-0-415-28073-0.

- ^ year old Mashed grapes found World's earliest evidence of crushed grapes

- ^ a b Introduction to Wine Laboratory Practices and Procedures, Jean L. Jacobson, Springer, p.84

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Brian Murray Fagan, 1996 Oxford Univ Pr, p.757

- ^ Wine: A Scientific Exploration, Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, CRC Press, p.66

- ^ Medieval France: an encyclopedia, William Westcott Kibler, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p.964

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- ^ "Ancient Thrace, the Motherland of Wine Culture | Code de Vino". Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Advertorial (17 November 2021). "Who Are the Thracians and Why Wine Was an Integral Part of Their Culture and Tradition 6000 Years Ago?". Wine Industry Advisor. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. New York, NY: Allsworth press. pp. 118–121. ISBN 9781581159332. OCLC 460134637.

- ^ Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, ed. (1999). Ancient Greeks West and East. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 429. ISBN 90-04-11190-5. OCLC 41320191.

- ^ "Ancient Thrace, the Motherland of Wine Culture | Code de Vino". Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Jellinek, E. M. 1976. "Drinkers and Alcoholics in Ancient Rome." Edited by Carole D. Yawney and Robert E. Popham. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 37 (11): 1718-1740.

- ^ J. Robinson (ed). The Oxford Companion to Wine, 3rd Ed., p. 234. Oxford Univ. Press (Oxford), 2006. ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ^ Dodd, Emlyn (January 2017). "Pressing Issues: A New Discovery in the Vineyard of Region I.20, Pompeii". Archeologia Classica.

- ^ Vitruvius. De architectura, I.4.2.

- ^ Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 72. Simon and Schuster 1989.

- ^ Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, Wine: A Scientific Exploration p. 66, 2003, ISBN 0203373944

- ^ Pliny. Natural History, XIV.61.

- ^ "History of Wine I". Life in Italy. 28 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ Cosano, Daniel; Manuel Román, Juan; Esquivel, Dolores; Lafont, Fernando; Ruiz Arrebola, José Rafael (1 September 2024). "New archaeochemical insights into Roman wine from Baetica". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 57: 104636. Bibcode:2024JArSR..57j4636C. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104636. ISSN 2352-409X.

- ^ "The Roman Wine of Speyer: The oldest Wine of the World that's still liquid". Deutsches Weininstitut. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Museum scared to open ancient Roman wine". The Local – Germany edition. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Tillier, Mathieu; Vanthieghem, Naïm (2 September 2022). "Des amphores rouges et des jarres vertes: Considérations sur la production et la consommation de boissons fermentées aux deux premiers siècles de l'hégire". Islamic Law and Society. 30 (1–2): 1–64. doi:10.1163/15685195-bja10025. ISSN 0928-9380. S2CID 252084558.

- ^ Rutman, Rabbi Yisrael. "Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It". Project Genesis Inc. Archived from the original on 24 December 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ Miller, Chaim. Chabad. "Rashi's Method of Biblical Commentary".

- ^

Langland, William (1885). Skeat, Walter William (ed.). The Vision of William Concerning Piers Plowman: Together with Vita de Dowel, Dobet, Et Dobest, and Richard the Redeles. Early English Text Society (Series).: Original series: 67. London: N. Trübner & Company. p. 433. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

Pigmentum, or pimentum, wine spiced, or mingled with honey, called in French piment, was formerly in high estimation.

- ^ a b "Wine | Definition, History, Varieties, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Hugh; Robinson, Jancis (2013). The World Atlas of Wine. Octopus Publishing Group. p. 376. ISBN 978-1784724030.

Further reading

edit- Patrick E. McGovern (2007). Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691127842.

- Patrick E. McGovern (2010). Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520267985.

- Emlyn K. Dodd (2020). Roman and Late Antique wine production in the eastern Mediterranean. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-78969-402-4

- Muraresku, Brian C. (2020). The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name. Macmillan USA. ISBN 978-1250207142

- Magris, Gabriele; Jurman, Irena; Fornasiero, Alice; Paparelli, Eleonora; Schwope, Rachel; Marroni, Fabio; Di Gaspero, Gabriele; Morgante, Michele (21 December 2021). "The genomes of 204 Vitis vinifera accessions reveal the origin of European wine grapes". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 7240. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.7240M. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27487-y. PMC 8692429. PMID 34934047.